Spontaneous Intracerebral Bleed Post Snake Envenomation

Girish Menon1, Lakshman I Kongwad2, Rajesh Parameshwaran Nair3, Anmol Nagaraj Gowda4

1 Professor and Head, Department of Neurosurgery, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Karnataka, India.

2 Assistant Professor and Head, Department of Neurosurgery, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, India.

3 Assistant Professor and Head, Department of Neurosurgery, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, India.

4 Neurosurgery Resident, Department of Neurosurgery, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal, Karnataka, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Lakshman I Kongwad, Assistant Professor and Head, Department of Neurosurgery, Kasturba Medical College, Madhav Nagar, Manipal-576104, Manipal, Karnataka, India.

E-mail: rajeshnair39@yahoo.com

Snakebite envenomation is a commonly encountered emergency in tropical countries with potentially fatal complications. Life threatening neurosurgical complications are rare and infrequently documented in literature. We discuss the case of 28-year-old gentleman, managed successfully for an intracerebral haemorrhage following a viper bite and attempt to obviate some management dilemmas often encountered in viperine envenomation.

Decompression, Haematotoxic venom, Intraparenchymal bleed, Viperine envenomation

Case Report

A 28-year-old male patient presented to the triage with an alleged history of snake bike, while walking by the roadside at dawn. His friends identified the snake to be a “kanthodi” or Viper, however they were unable to capture it. He fell unconscious soon after the incident and was brought within 30 minutes to the triage. There were no spontaneous bleeding manifestations, either, local, or systemic.

On admission his vitals were stable. He was not opening eyes to painful stimuli but he was moving all four limbs spontaneously. Both his conjunctiva appeared congested. He did not show any sign of systemic envenomation in the form of diffuse spontaneous bleeding from mucosal surfaces or haematemesis. No signs of central or peripheral cyanosis or compartment syndrome. His pupils were equal and reacting well and there were no cerebral localizing signs in the form of hemiparesis or plegia. A plain Computed Tomographic scan of the brain (CT Brain) was done, which was normal [Table/Fig-1a-c].

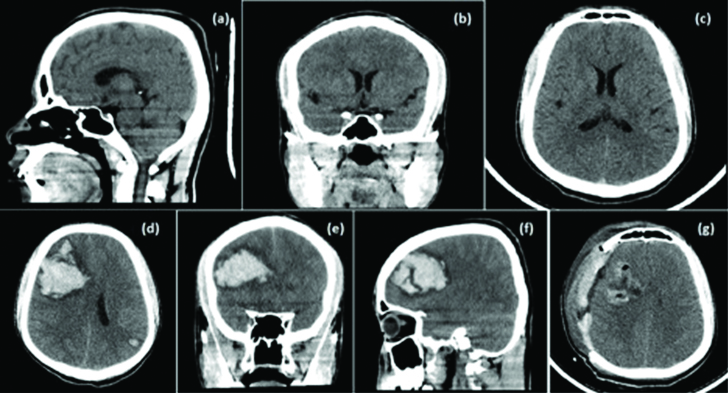

Computed tomographic scan (CT Brain) of the brain showing: a-c) Sagittal, coronal and axial respectively) grossly normal scan, taken at the time of admission. Repeat CT scan done after the partial seizure; d) axial section; e) coronal; and f) sagittal sections showing right frontal lobar haematoma with uncal and parafalcine herniation with cerebral oedema. The postop CT scan of the brain; g) showing complete evacuation of haematoma with craniectomy defect and persistent cerebral oedema.

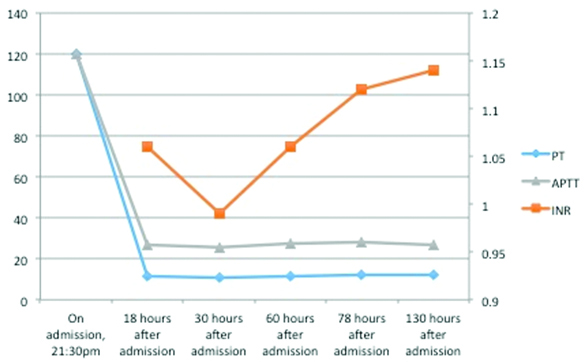

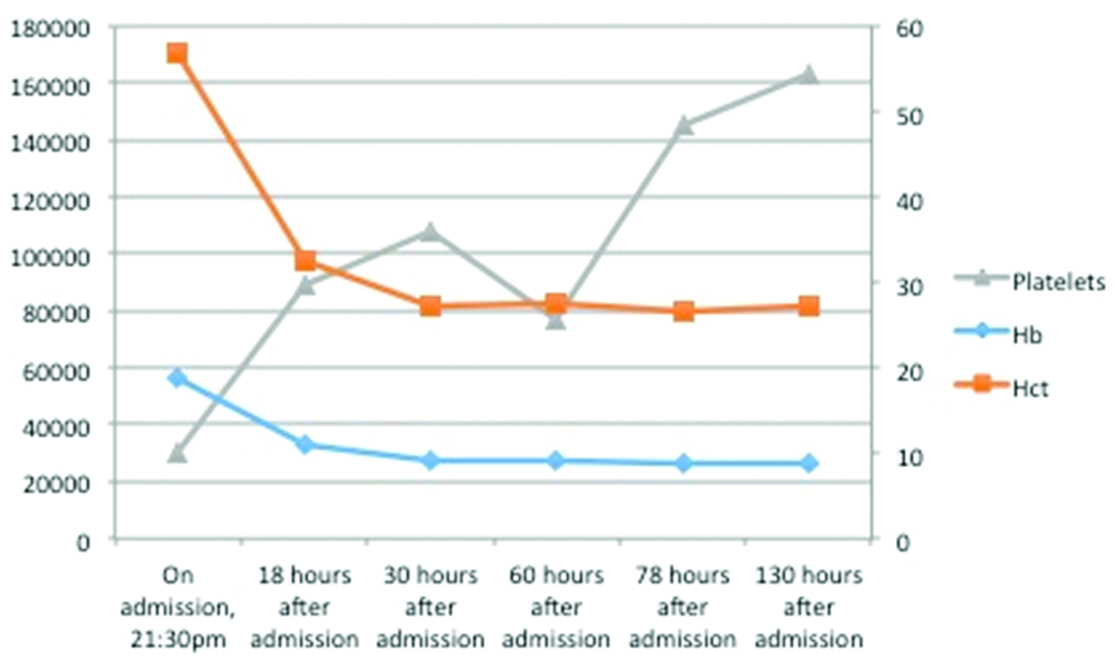

He was started on Anti Snake Venom (ASV) as per guidelines and supportive treatment was started. Two days following his admission, he had an episode of focal seizures involving the right upper and lower limb. A repeat CT Brain was done which showed a large intraparenchymal bleed in the right frontal region with uncal and right parafalcine herniation with significant cerebral oedema [Table/Fig-1d-f]. Blood investigations revealed features of Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) [Table/Fig-2,3]. The investigations revealed thrombocytopenia with elevated Prothrombin Time/International Normalized Ratio (PT/INR), Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (aPTT), positive D-dimer {normal value is less than 0.5μg/ml fibrinogen equivalent unit (FEU)} and other fibrinogen degradation products (normal value - less than 10mcg/ml) (FDPs) with depleted levels of plasma fibrinogen (normal values 150-400mg/dl). Other haematological investigations revealed an elevated reticulocyte count, elevated indirect and total bilirubin with raised Lactate Dehydrogenase (LDH) levels, suggestive of a haemolyticanaemia. The peripheral smear showed immature RBCs, spherocytes with reduced platelets, fragmented RBCs and polychromasia, suggestive of haemolytic anaemia.

A line graph showing the PT/INR and aPTT values during the hospital stay and symptomatic treatment showing a significant improvement in the coagulation profile.

Fluctuation in platelets, showing thrombocytopenia (at the time of admission) and the response to treatment along with spontaneous drop in platelets and the response following platelet transfusion. The effect of the haematotoxic viperine venom showing a drop in Hb from the time of admission and a concurrent drop in Hematocrit (Hct) and the response after transfusion with the plateau in Hb achieved thereafter.

Fresh Frozen Plasma (FFPs) and platelet transfusions were administered and he was taken up for an emergency right frontal decompressive craniotomy and evacuation of haematoma [Table/Fig-1g]. He was gradually weaned of ventilator and extubated after 24 hours. ASV was continued with adequate transfusion of blood products (FFPs, platelets and packed cells). His platelets gradually increased to normal levels and he was discharged after suture removal [Table/Fig-4].

The sequential laboratory parameters of the patient since his admission.

| Timeline | PT | INR | aPTT | Platelets | Hb | Hct |

|---|

| On admission, 21:30pm | 120 | | 120 | 30000 | 18.8 | 56.9 |

| 18 hours after admission | 11.4 | 1.06 | 26.5 | 89000 | 10.9 | 32.6 |

| 30 hours after admission | 10.7 | 0.99 | 25.6 | 108000 | 9 | 27.1 |

| 60 hours after admission | 11.4 | 1.06 | 27.5 | 77000 | 9.1 | 27.4 |

| 78 hours after admission | 12 | 1.12 | 27.9 | 145000 | 8.8 | 26.6 |

| 130 hours after admission | 12.2 | 1.14 | 26.8 | 163000 | 8.8 | 27.2 |

He was discharged on anticovulsants (leviteracetam), haematinics and analgesics and asked to return to the clinic for follow up after three weeks.

Discussion

Snake envenomation is a potentially fatal disease common to the developing world. Most snake-bites are delivered by non-poisonous snakes and only 15% of snakes, are considered poisonous [1]. The family Viperidae is the largest family of poisonous snakes followed by Elapidae and the sub-family Crotalidae. Cerebrovascular complications following snake-bite is uncommon, but both haemorrhagic and thrombotic complications have been reported in literature [2,3].

The pathophysiology of coagulopathy following snake envenomation is incompletely understood. The different components in venom have different roles in the spread of the toxin and its characteristic clinical manifestation. The most common coagulopathy associated with snake-bite envenoming is Venom Induced Consumptive Coagulopathy (VICC). Viperine venom has different concentrations of enzymes that include proteases, phospholipase A2, hyaluronidase and arginine ester hydrolase. The hyaluronidase causes spread of the venom in the subcutaneous tissue by disrupting mucopolysaccharides and phospholipase A2 is the factor responsible for the haematological complications. They cause haemolysis secondary to the esterolytic effect on the red cell membranes and promote muscle necrosis.

Thrombogenic enzymes act in conjunction with these enzymes to promote the formation of weak fibrin clots which inturn activate plasmin and result in consumption coagulopathy and haemorrhagic consequences [4]. It also contains prothrombin activators (ecarin and carina activase) causing variable deficiency in factor V, VII and fibrinogen [5]. In the present case scenario the patient had significant increase in PT, INR, aPTT, thrombocytopenia and increase in FDP, which suggests DIC as the probable cause for intracerebral haemorrhage [6]. Alterations in laboratory parameters do not always equate with actual haemorrhagic risks. Similarly, recurrence and late relapse of laboratory abnormalities and clinical signs and symptoms are known to occur after initial correction. This is supposedly due to the delayed seepage of venom from deeper reservoirs in the bite site or due to disassembly of the antigen-antibody complex with reinstitution of circulating unbound venom constituents. This probably explains the delayed appearance of intracerebral haemorrhage in our patient as quoted by Kularatne SAM et al., and Kumar N et al., [7,8].

Treatment should be given at the earliest which halts the progression of the cascade of bleeding mechanism. ASV is the definitive treatment of poisonous snake-bites and it helps in neutralizing the circulating toxin. WHO guidelines dictate that 100ml of polyvalent ASV is to be given initially after skin testing for systemic envenomation in Viperidae family. Repeat dose of 100 ml ASV is to be given one to two hours of the first dose if there is no clinical improvement or if neurological manifestations occur or the patients’ condition deteriorates. ASV is continued in patients with persistence or recurrence of blood incoagulability after six hours of first dose, in patients who continue to bleed briskly after one to two hours of first dose of ASV and in deteriorating neurologic and cardiovascular signs after one to two hours of first dose of ASV. Coagulation abnormalities usually revert following administration of ASV, but that is not the rule. The use of FFP in VICC remains controversial although some studies have proven that FFP replacement was associated with faster recovery and reduced risk of bleeding [9].

In our case, ASV therapy was started immediately on arrival to the triage and continued in view of worsening neurological status after the first dose of ASV. The PT, INR and aPTT were grossly deranged with significant drop in platelets, which mandated repeated transfusions of FFPs and packed cells. As such, institution of blood and blood products are not indicated in DIC but in our patient the impending risk of an intraparenchymal bleed and need for surgical intervention mandated the need for such therapy. Once the patient had developed seizures secondary to a large lobar haematoma, surgical evacuation was warranted and he was taken up for surgery under cover of platelet infusions and FFPs to increase the total platelet levels to avoid intraoperative and postoperative re-bleeds.

Conclusion

Intracerebral haemorrhage is an uncommon but potentially fatal complication of viper envenomisation. Early detection with prompt initiation of ASV coupled with FFP and timely surgery can result in good outcome.

[1]. Barlow A, Pook CE, Harrison RA, Wüster W, Coevolution of diet and prey-specific venom activity supports the role of selection in snake venom evolutionProc Biol Sci 2009 276(1666):2443-49. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Gouda S, Pandit V, Seshadri S, Valsalan R, Vikas M, Posterior circulation ischemic stroke following Russell’s viper envenomationAnn Indian Acad Neurol 2011 14(4):301-03. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Ittyachen AM, Jose MB, Thalamic infarction following a Russell’s viper biteSoutheast Asian J Trop Med Pub Health 2012 43(5):1201-04. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Gold BS, Dart RC, Barish RA, Bites of venomous snakesN Engl J Med 2002 347(5):347-56. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Cortelazzo A, Guerranti R, Bini L, Hope-Onyekwere N, Muzzi C, Leoncini R, Effects of snake venom proteases on human fibrinogen chainsBlood Transfus 2010 8(Suppl 3):120-25. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Warrell DA ed. WHO/SEARO guidelines for the clinical management snakebite in South-East Asia region New Delhi (2005). 01067 [Google Scholar]

[7]. Kularatne SAM, Sivansuthan S, Medagedara SC, Maduwage K, de Silva A, Revisiting saw-scaled viper (Echiscarinatus) bites in the Jaffna Peninsula of Sri Lanka: distribution, epidemiology and clinical manifestationsTrans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2011 105:591-97. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Kumar N, Mukherjee S, Patel MP, Shah KB, Kumar S, A case of saw scale viper snake bite presenting as intraparenchymal haemorrhage: case reportInt J Health Sci Res 2014 4(10):333-37. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Isbister GK, Duffull SB, Brown SG, ASP Investigators, Failure of antivenom to improve recovery in Australian snakebite coagulopathyQJM 2009 102(8):563-68. [Google Scholar]