The use of plants for the purposes of healing predates recorded history. Researchers found that people in different parts of the world tend to use the same plants for the similar purposes. Chinese and Egyptian papyrus records of ancient times described the medicinal uses of plants as early as 3,000 BC. Indigenous cultures such as African and Native American habituated herbs in their healing rituals, while others evolved with traditional medical systems such as Ayurvedic and traditional Chinese medicine. In recent years, interest towards herbal medicine is greatly increased, leading to scientific heed in the medicinal use of plants to treat various ailments and enhance general health and well being.

Dental caries is an infectious microbiologic disease of the teeth since ages and has an increased incidence in recent past due to radical changes in lifestyle habits [1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that four billion people (about 80% of the world’s population) living in the developing world relies on herbal medicinal products as a primary source of healthcare and traditional medical practice [2]. This shift is because herbs work by enhancing the natural physiological functions and defensive healing reactions of the organisms. Many modern drugs on the other hand inhibit key bodily functions and obstruct these natural healing reactions. Herbal medicines follow the key Hippocratic precept: First, do no harm. The major benefits of using natural products are ease of availability, cost effectiveness, increased shelf life, low toxicity and lack of microbial resistance reported so far [3].

The use of antimicrobial mouth rinses has been proposed as a means for the prevention of dental caries in children and adolescents was established as a mass prophylactic and therapeutic method in the 1960s and has shown an average efficacy of caries reduction between 20 and 50% [4].

The ability of these rinses to reduce plaque, freshen breath, to prevent or control tooth decay, to reduce gingivitis, to reduce the speed that tartar forms on the teeth, or to produce a combination of these effects [5]. Although the use of herbal mouth rinses in orthodontic treatment seems to be not enough in controlling dental plaque and has been suggested as the supplement of oral hygiene practices.

Materials and Methods

The study was conducted in the Department of Public Health Dentistry, Institute of Dental Sciences, Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, India, from March 2014 to July 2014. The duration of the study was three months. Dried ripe fruits of T. chebula, T. bellirica, and E. officinalis were obtained from the local seed supplier and they were identified and reconfirmed by two botanists. The seeds were extracted from the ripe fruits and they were crushed and grounded separately into fine powder using mortar and pestle. The three powders were placed in separate containers.

Triphala was prepared by adding equal parts 1:1:1 of T. chebula, T. bellirica and E. officinalis. It was placed in another container. A 10% extract of each powder was prepared by adding 50 grams of the respective powder to 1 litre of normal saline. Thus, four different solutions namely T. chebula solution, T. bellirica solution, E. officinalis solution and Triphala solution were prepared and boiled separately for 10 minutes, cooled and filtered. The preparation was done by the author in pharmacology department with the help of trained assistant. The resultant solutions were the 10% extracts of the respective seeds. These herbal preparations were further used as mouth rinses in the present study.

The current study was a double blinded (microbiologist and participant), linear cross over trial. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board and informed written consent was obtained from the subjects and also informed written consent was obtained from parents whose children were below 18 years after getting approval by Ethical Clearance Committee of Institute of Dental Sciences, Bareilly before conducting the study. This research has been conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The subjects were selected from a pool of patients visiting the department based on carefully planned selection criteria.

The inclusion criteria for entering in this study were: 15-40 years of age; presence of active and untreated carious lesions and subjects willing to participate in the study and provide informed written consent which was also taken from the parents whose children were below 18 years. The subjects who were excluded from the study; patients who were on antibiotic therapy in the last six months, usage of any antimicrobial rinse in the last one month, having any systemic health problems and with no history of allergy to herbal preparations which was ascertained by asking the patient before commencement of the study. A random sample of 40 subjects was selected from a pool of patients visiting the department for treatment. All the selected subjects were exposed to all the four different mouth rinses.

Group 1- T. chebula, Group 2- T. bellirica, Group 3- E. officinalis, Group 4- Triphala

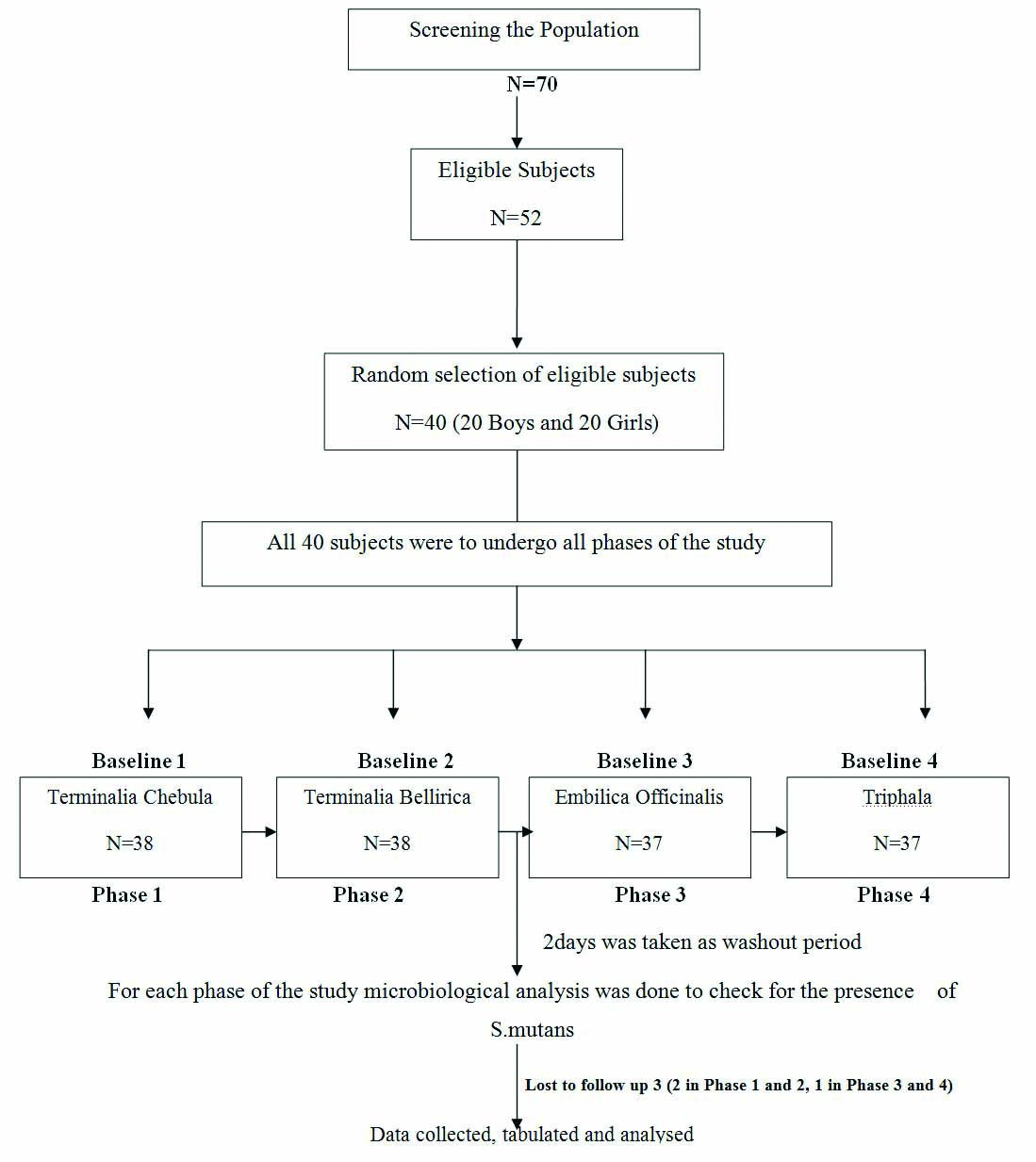

Since, it is a linear cross over trial all subjects were exposed to all four interventions in multiple phases. There were three dropouts in the study which was due to altered taste. The sequence of interventions was generated randomly. The details of it are provided in a schematic diagram [Table/Fig-1].

Diagrammatic representation of methodology.

A two days interval was maintained between the interventions as a wash out period which was decided by the baseline values [12]. The subjects were instructed to have breakfast at least two hours before visiting the department on the given date. Unstimulated salivary samples were collected by instructing the subjects to pool the saliva in the floor of the mouth which was followed by collection in sterile syringes. They were placed into respective sterile containers and duly labelled. This constituted the baseline salivary samples (pre-test salivary samples).

All the subjects were provided 15 ml of the freshly prepared 10% rinse of T. chebula, T. bellirica, E. officinalis and Triphala as according to the order of four phases. The subjects were instructed to hold the rinse in the mouth and swish it around the teeth and the oral cavity vigorously for one minute and then expectorate the solution. Post rinse unstimulated salivary samples were again collected at 5 minutes and 60 minutes intervals. The subjects were instructed not to eat or drink between salivary samples collection. All the salivary samples were transferred immediately to microbiological laboratory in sterile containers within one hour for microbiological analysis.

The order of interventions is given below:

Phase 1 Day 1 T. chebula

Phase 2 Day 3 T. bellirica

Phase 3 Day 5 E. officinalis

Phase 4 Day 7 Triphala

Microbiological Analysis

Collected salivary samples were labelled which was blinded to microbiologists. Mitis Salivarius Agar (MSA) with bacitracin was prepared for evaluating the S. mutans colony count. Each saliva sample was streaked onto MSA containing bacitracin to determine the S. mutans colony count respectively. The plates were then incubated for 16-18 hours at 37°C and the number of bacterial colonies was counted under self-illuminating binocular microscope (Models name Ch20 i, Olympus). Wells of 4 mm diameter were formed on to the agar plates using a loop method recommended for the S. mutans colony count.

Statistical Analysis

The microbial counts were converted to log values and the data so obtained were compiled and entered into excel sheets which was further transferred to SPSS 19 for generating tables and doing inferential statistical analysis. Between group comparisons of salivary S. mutans was done by One-way ANOVA. Post-hoc analysis using Tukey’s test was done for pair wise comparisons at 5 minutes and 60 minutes after the rinse. One-way ANOVA with post-hoc Tukey’s HSD test is done for comparing multiple treatments. Tukey’s is done after the analysis of variance.

Within group, comparisons was done using repeated measures (r ANOVA).

Results

Results of salivary S. mutans count before and after rinsing with T. chebula, T. bellirica, E. officinalis and Triphala have been presented in [Table/Fig-2,3 and 4].

Inter group comparison of salivary S. mutans count, using one-way ANOVA.

| Time Interval and Intervention | N | Mean CFU | Std. Deviation | 95% CI | F-value | Reduction | p-value |

|---|

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

|---|

| Baseline | Mouthrinse Terminalia Chebula (1) | 37 | 162.7027 | 24.08303 | 154.6730 | 170.7324 | 1.17 | _ | 0.32 |

| Mouthrinse Terminalia Bellirica (2) | 37 | 162.5676 | 23.93921 | 154.5858 | 170.5493 | _ |

| Mouthrinse Embilica Officinalis (3) | 37 | 164.0541 | 22.99873 | 156.3859 | 171.7222 | _ |

| Mouthrinse Triphala (4) | 37 | 171.6216 | 25.52379 | 163.1116 | 180.1317 | _ |

| 5 minutes | Mouthrinse Terminalia Chebula (1) | 37 | 117.9730 | 22.03090 | 110.6275 | 125.3184 | 17.53 | 44.73 | 0.001 |

| Mouthrinse Terminalia Bellirica (2) | 37 | 129.0541 | 20.06371 | 122.3645 | 135.7436 | 33.51 |

| Mouthrinse Embilica Officinalis (3) | 37 | 141.3514 | 20.16077 | 134.6294 | 148.0733 | 22.70 |

| Mouthrinse Triphala (4) | 37 | 107.4324 | 22.34893 | 99.9809 | 114.8839 | 64.19 |

| 60 minutes | Mouthrinse Terminalia Chebula (1) | 37 | 116.6216 | 23.15569 | 108.9011 | 124.3421 | 25.84 | 46.08 | 0.001 |

| Mouthrinse Terminalia Bellirica (2) | 37 | 127.8378 | 20.63373 | 120.9582 | 134.7175 | 34.73 |

| Mouthrinse Embilica Officinalis (3) | 37 | 145.9459 | 20.87788 | 138.9849 | 152.9070 | 18.11 |

| Mouthrinse Triphala (4) | 37 | 102.4324 | 23.17271 | 94.7063 | 110.1586 | 69.19 |

CI - Confidence Interval

Post-hoc analysis for pair wise comparison using Tukey’s test (5 mins after the rinse).

| Groups | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|

| 1 T. chebula | NS | 0.001 | N.S |

| 2 T. bellirica | --------- | NS | 0.001 |

| 3 E. officinalis | NS | --------- | 0.001 |

Post-hoc analysis for pair wise comparison using Tukey’s test (60 mins after the rinse)

| Groups | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|

| 1 | NS | 0.001 | 0.03 |

| 2 | --------- | 0.003 | 0.001 |

| 3 | NS | ------- | 0.001 |

[Table/Fig-2] depicts inter group comparisons of salivary S. mutans count by using one-way ANOVA. At baseline, there was no significant difference in mean CFUs of salivary S. mutans between the four groups with a p-value 0.32 and F-value 1.17.

Results of inter group comparision (at different time interval), mean CFUs and maximum reduction in the colony counts of various herbal mouth rinses included in the study have been presented in [Table/Fig-2].

[Table/Fig-3,4] present post hoc analysis for pair wise comparison using Tukey’s HSD test at five minutes and 60 minutes after rinse respectively.

[Table/Fig-5] presents intra group comparisons by using repeated measures ANOVA. Within group, comparisons were found to be statistically significant in all groups.

Shows intra group comparison using repeated measures ANOVA.

| Groups | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | F- value | p*- value |

|---|

| MouthrinseT. chebula | Baseline | 37 | 162.7027 | 24.08303 | 348.13 | 0.001 |

| 5 minutes | 37 | 117.9730 | 22.03090 |

| 60 minutes | 37 | 116.6216 | 23.15569 |

| MouthrinseT. Bellirica | Baseline | 37 | 162.5676 | 23.93921 | 215.43 | 0.001 |

| 5 minutes | 37 | 129.0541 | 20.06371 |

| 60 minutes | 37 | 127.8378 | 20.63373 |

| MouthrinseE. officinalis | Baseline | 37 | 164.0541 | 22.99873 | 194.62 | 0.001 |

| 5 minutes | 37 | 141.3514 | 20.16077 |

| 60 minutes | 37 | 145.9459 | 20.87788 |

| Mouthrinse Triphala | Baseline | 37 | 171.6216 | 25.52379 | 519.53 | 0.001 |

| 5 minutes | 37 | 107.4324 | 22.34893 |

| 60 minutes | 37 | 102.4324 | 23.17271 |

*Repeated Measures ANOVA

The results of the study clearly indicate that Triphala mouth rinse is very effective in reducing the S. mutans CFUs at 5 and 60 minutes after rinse.

Discussion

WHO supports indigenous systems of health care which is found to be potent and beneficial. This translates the health care delivery into a cost effective measure [13]. Traditional herbal medicines comprises of plant derived substances with minimal or no industrial processing which is used to treat diseases within local or regional healing practices. Developing countries cannot afford increasing cost of health care. There is renewed interest in traditional medicines. Many countries including the indian subcontinent, China, United States of America as well as WHO have recently invested substantially in research of traditional herbal medicine. Managing health has become an expensive affair [14]. Oral health is no exception. Dental caries continues to plague most of the world’s population. Therefore, more efficient and effective public health awareness and preventive measures are mandatory to gauge this worldwide problem. S. mutans is the primary aetiological agent of dental caries and is transmissible [15].

This study was conducted to assess the antibacterial efficacy of T. chebula, T. bellirica, E. officinalis and Triphala mouthwash against oral streptococci. In present study, a statistically significant reduction in mean CFUs/ml of oral streptococci was seen after using Triphala as well as T. chebula at the end of 5 minutes and 60 minutes after rinsing. This is similar to the studies reported in the literature [16]. The other rinses were not as effective although they were able to reduce oral streptococci.

Ayurvedic drugs have been used since time immemorial. Triphala can be used as a gargling agent in dental diseases as already reported in Susruta Samhita. Many systemic diseases have been treated by Ayurvedic practitioners through Triphala. No literature has reported any evidence of harmful effects of Triphala on swallowing. The ingredients used to prepare Triphala are the frequently available fruit derivatives. It is prepared by mixing the dried and powdered mixture of Triphala constituted by amla, vibhitakai and haritakai in a 1:1:1 ratio which is quite economical. Thus, it could form a possible and practicable cost effective alternative to our rural population who find the commercially available toothpastes to be quite extortionate and unaffordable [7].

The unique aspect of the work is to confirm the importance of herbal product for its antimicrobial relation. Triphala (equal proportion of T. chebula, T. bellirica and E. officinalis) showed significant reduction in colony forming unit of S. mutans at 5 and 60 minutes. But when its constituents were used individually none of them were found to be as potent antimicrobial as when they were in combination. Although T. chebula and T. bellirica showed significant reductions in S. mutans count they were not as effective as Triphala. E. officinalis was least anti microbial.

No study till now has reported comparative antibacterial efficacy of Triphala mouth rinse and its individual components as mouth rinse used separately. T. chebula is called the “king of medicines” in Tibet and is always listed first in Ayurvedic Materia Medica in India [10]. T. chebula fruit has been used as a traditional medicine against various ailments since antiquity. It exerts a wide range of pharmacological effects, including antibacterial, antiviral (against herpes simplex virus and HIV) and antifungal (against candida albicans) activities. In the present study, there was a significant reduction in the S. mutans colony count five and 60 minutes after rinsing with the extract of T. chebula. Similar findings have been reported earlier by various researchers. A 10% concentrate was used in this study since it has already been proved to be effective which is similar to the studies already reported in the literature [1,10].

The strong antioxidant activity of Triphala may be attributed to T. bellirica, which is the most active antioxidant followed by E. officinalis and T. chebula partially responsible for many of the biological properties [17]. The major ingredients of T. bellirica are ellagic and gallic acid; E. officinalis has several gallic acid derivatives including epigallocatechin gallate and in T. chebula the chief constituents are chebulic acid, chebulagic acid, corilagin and gallic acid. The active ingredients of phenolic nature present in triphala can be accounted for the scavenging of free radicals [18].

Only few studies on clinical trials of herbal mouthwashes have been reported in the literature with E. officinalis and T. bellirica in reducing S. mutans count [19]. Tannic acid is found to be the major constituent of the ripe fruit of T. chebula, T. bellirica and E. officinalis [20]. They have large phenolic groups that provide them with unique binding properties causing them to bind to mucosal and tooth surfaces and this results in the prolonged action of the extract [21].

Limitation

The limitation of the study was that duration between these mouth rinses was only for two days. The antimicrobial effect was measured only for one hour. How long the effect is going to be sustained is another issue based on that the frequency of rinsing has to be determined. This study has opened new gateways for further research and carries future benefit since results seem to be encouraging.

Conclusion

Triphala in 10% concentration used once in a day as a mouth rinse brought down the oral streptococci count by the end of 60 minutes significantly. When individual ingredients of Triphala were used separately as mouth rinses they were not as effective. E. officinalis was found to be least effective. Triphala extract may be recommended as an antibacterial mouthwash in prevention of dental caries.

CI - Confidence Interval

*Repeated Measures ANOVA