Teratomas are benign tumours containing cells from ectodermal, mesodermal and endodermal layers with an incidence of about 1 in every 4,000 births. Their commonest site is sacro-coccygeal region, followed by anterior mediastinum. The incidence of teratomas localised to the head and neck region is around 2–9% of all cases. Epignathus is a rare congenital oropharyngeal teratoma originating from the base of the skull. Here we present a rare case of oropharyngeal teratoma in a neonate who was referred to our institute with an ill-defined oral mass protruding through a cleft in the hard palate. Computed tomography scan showed a contrast-enhanced solid mass with areas of calcification and fat extending to oropharynx and nasal cavity with hard palate defect suggestive of a teratoma. Unfortunately, the patient succumbed due to respiratory compromise before the biopsy could be done. Postmortem histopathological examination confirmed diagnosis of benign teratoma consisting of mature tissue.

Cleft palate, Congenital teratoma, Oropharyngeal teratoma

Case Report

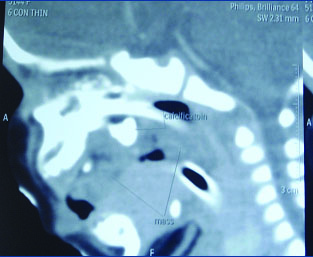

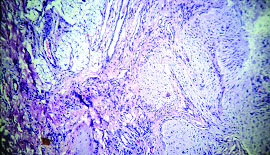

A 12-day-old, 2.6 kg, full term female neonate, born vaginally, with no significant antenatal history except for polyhydramnios, was referred to us from a peripheral hospital with endotracheal tube in situ and airway obstruction due to a mass in oral cavity. This mass was noticed by mother on day one of life itself resulting in respiratory distress and feeding difficulty. Oral cavity examination revealed an ill-defined oropharyngeal mass with cleft palate [Table/Fig-1]. Systemic examination was normal. Baby was ventilated and appropriately treated for sepsis. A computed tomography scan showed a contrast-enhanced solid mass with areas of calcification and fats extending to oropharynx and nasal cavity with hard palate defect suggestive of teratoma [Table/Fig-2]. Biopsy of the mass was planned in consultation with the ENT Oncologist. Unfortunately, the child succumbed on day 16 of life before biopsy could be done. Postmortem histopathological examination clinched the diagnosis of mature teratoma consisting of glial, squamous epithelium, skeletal and fibromuscular tissue components [Table/Fig-3].

Protruding Mass in the oral cavity with cleft palate.

Computed Tomography of Para nasal Sinuses – Mild Enhancing mass in oral cavity with areas of calcification and fat extending to oropharynx and nasal cavity.

Histopathological slide of the mass showing fatty, glial and fibro muscular tissue.

Discussion

Teratomas are exceptionally rare tumours in the head and neck region. Neonatal teratomas occur in about 1 in 4000 live births with less than 10% occurring in the head and neck region [1–3]. The word ‘teratoma’ was coined by Virchow which has originated from the Greek word ‘teraton’ meaning ‘monster’ [3]. Epignathus, is a rare form of teratoma originating from the base of skull usually attached to the hard palate or the mandible [4].

Teratomas are tumours derived from pluripotent stem cells and consist of various tissue elements derived from the endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm [1–3]. Teratomas occur rarely in neonates and show a female predominance (female:male ratio- 3:1) [1–3,5]. Teratomas are most commonly seen in the sacro-coccygeal region, followed by anterior mediastinum, testis, ovaries, retroperitoneum, and head and neck region, which comprises only 10% of total reported cases [4,6,7]. Head and neck teratomas are commonly situated in the cervical region with oropharynx (epignathus) being the second commonest location [3].

The teratomas originating from the soft or hard palate in the region of the Rathke’s pouch are called epignathi. They can also be found in the nasopharyngeal areas like the basisphenoid, tongue, sinuses, mandible or tonsil [4,6].

Exact aetiopathogenesis of teratoma development is not known, however according to the most popular theory, it is speculated that the totipotential embryonic tissues adjacent to the primitive streak and notochord are displaced by some unknown mechanism during ontogenesis. The influence of governing cells on these displaced tissues is lost leading to unorganised differentiation with resultant teratoma formation [3]. Teratomas can be histologically classified into 4 groups: (a) Dermoid cysts consisting of epithelial cells lined with skin elements composed of ectodermal and mesodermal cells; (b) Teratoid cysts which are composed of all three germ cell layers and poorly differentiated; (c) Teratomas consisting of all three germinal cell layers which are differentiated into specific tissues or organs; (d) Epignathi which are highly developed rare oral tumours with developmental fetal organs and limbs, with a high mortality rate [2,8,9]. The tissues that are often found in these tumours consist of brain, cartilage, bronchial epithelium and cystic tissues. Another pathological variant of epignathi is ‘fetus-in-fetu’ occurring due to the incomplete twinning of monozygotic twins at a primitive stage of the beginning of axial development [8,9].

Epignathus is a rare form of teratoma and it is attached to the base of the skull, usually to the hard palate or the mandible [4,6]. An epignathus is found in approximately 1:35,000 to 1:200,000 live births [1–3]. The clinical presentation varies depending on the size of the lesion. The neonate may be either asymptomatic or may present with feeding difficulty, stridor, recurrent apnoea or recurrent respiratory distress [7,8,10]. Giant epignathi that are present at birth fill the oral cavity and protrude from the mouth resulting in respiratory compromise as a consequence of upper airway obstruction [4,7]. In our case the teratoma was huge enough to cause respiratory compromise along with feeding problems.

Various authors have reported that the incidence of anomalies associated with epignathi varies from 6 to 20% with cleft palate being the most common anomaly [2,3,11]. Reports of cardiac abnormalities (atrial and ventricular septal defects) and facial deformity with oral teratomas have also been observed [4,6,11]. Our case was not associated with any clinical malformations except for cleft palate. Most teratomas presenting during the neonatal and early childhood period are benign whereas those presenting in older children and young adults are malignant [1,11]. The histopathological examination in our case had shown mature tissue components suggesting its benign nature.

Securing the airway is the most common difficulty faced postnatally due to the large obstructing mass. Hence, the antenatal diagnosis of teratoma during routine ultrasounds done at 15–17 weeks or by a fetal anomaly scan is important for appropriate and timely patient management. However, the early diagnosis of epignathi is difficult on ultrasonography due to its rarity, complex distribution and their similar appearance to other lesions like hamartoma, dermoid cyst and heterogeneous gastrointestinal cyst [1,12]. More precise prenatal diagnosis can be achieved by 3-D ultrasound and MRI scans which can accurately detect the location, extension as well as the intracranial spread of the tumour [2,5]. Epignathi are associated with raised amniotic fluid alpha-feto protein prenatally [5]. Antenatal complications in mother may range from preeclampsia, polyhydramnios and hydrops leading to intrauterine fetal death [2,5].

In the neonatal period, both CT and MRI are useful imaging modalities, with MRI having the advantage of detecting the tumour with respect to its extension and relationship with surrounding structures [9]. Teratomas give a strong signal on T1-weighted images due to their high fat content and thus can be differentiated from cystic hygromas which give a strong signal only on T2-weighted images. CT scan may be advantageous to pick up bony defects and calcifications (seen in 50% of teratomas). For antenatally diagnosed teratoma, elective Caesarean section with EXIT (ex-utero intrapartum treatment) procedure or OOPS (operation on placental support) procedure offers best chance of survival of the neonate [1,2,4].

Complete surgical excision followed by repair of associated anomalies as soon as patient is stabilized is the management of choice. Prognosis depends on the extent and site of lesion. Intracranial extension is a predictor of poor outcome [1,2,6]. The risk of a malignant relapse increases in the case of an incomplete resection and presence of primitive neural tissue in the tumour [8,11]. Epignathus is not considered to be inherited in a Mendelian or polygenic fashion. It is important, therefore, that the parents are antenatally counselled and reassured by the obstetricians regarding absence of risk of bearing another child with epignathus [5,12].

Conclusion

Epignathus is a rare clinical entity causing respiratory compromise leading to life threatening airway obstruction and feeding difficulty. Accurate in utero diagnosis permits early multidisciplinary management. Airway stabilisation followed by complete surgical removal on an urgent basis improves survival.

Informed Consent: Written informed consent could not be obtained from the patient’s legal guardian (mother) for publication of this case report and any accompanying images as they were not contactable after the death of this child.

Authors Contribution: All authors were involved in the case management. SJ and CSK drafted the manuscript that was approved by all authors.SM, VS and SL gave critical inputs to the final manuscript draft. SM will be the guarantor.

Data and supporting materials are available with the authors.

[1]. Ahmadi M, Dalband M, Shariatpanahi E, Oral teratoma (epignathus) in a newborn: A case reportJ Oral Maxillofac Surg Med Pathol 2012 24:59-62. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Kontopoulas E, Gualtieri M, Quintero R, Successful in utero treatment of an oral teratoma via operative fetoscopy: case report and review of the literatureAm J Obstet Gynecol 2012 207(1):e12-15. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Shah A, Latoo S, Ahmed I, Malik A, Head and neck teratomasJ Maxillofac oral Surg 2009 8(1):60-63. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Lionel J, Valvoda M, Hadi K, “Giant Epignathus”-A Case ReportKuwait Med J 2004 36(3):217-20. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Clement K, Chamberlain P, Boyd P, Molyneux A, Prenatal diagnosis of an epignathus: a case report and review of the literatureUltrasound obstet gynecol 2001 18:178-81. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Too S, Sarji S, Yik Y, Ramanujan T, Malignant epignathus teratomaBiomed Imaging Interv J 2008 4(2):e18 [Google Scholar]

[7]. Halterman S, Igulada K, SteInicki E, Epignathus: Large Obstructive Teratoma Arising From the PalateCleft Palate Craniofac J 2006 43(2):244-46. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Mirshemirani A, Khalegnnejad A, Mohajerradeh L, Samasani M, Hasas-yeganeh S, Congenital nasopharyngeal teratoma in neonateIran J Pediatr 2011 21920:249-52. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Chauhan D, Guruprasad Y, Inderchand S, Congenital Nasopharyngeal Teratoma with a Cleft Palate: case report and 7 year follow upJ Maxillofac Oral Surg 2011 10(3):253-56. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Manjuladevi M, Kilpadi K, Jose J, Kothari A, Missed nasopharyngeal teratoma: A cause for recurrent respiratory distress in a neonateIndian J Anaesth 2014 58(3):338-41. [Google Scholar]

[11]. Hu R, Jiang RS, The Recurrence of a soft palate teratoma in a neonate: a case reportHead Neck Oncol 2013 5(2):16 [Google Scholar]

[12]. Tsitouridis I, Sidiropoulos D, Michaelides M, Sonographic evaluation of epignathusHippocratia 2009 13(1):55-57. [Google Scholar]