Management of Oehlers Type II Dens in Dente with Open Apex and Alveolar Bone Defect

Ruchi Srivastava1, Pushpendra Kumar Verma2, Vivek Tripathi3, Pragya Tripathi4, Ayush Razdan Singh5

1 Reader, Department of Periodontology, Saraswati Dental College, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India.

2 Reader, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saraswati Dental College, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India.

3 Senior Lecturer, Department of Periodontology, Azamgarh Dental College, Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh, India.

4 Senior Lecturer, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Mithila Minority Dental College and Hospital, Darbanga, Bihar, India.

5 Reader, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saraswati Dental College, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Ruchi Srivastava, Reader, Department of Periodontology, Saraswati Dental College, Lucknow-227105, Uttar Pradesh, India.

E-mail: drruchi117@gmail.com

Apexification, MTA, Periapical surgery

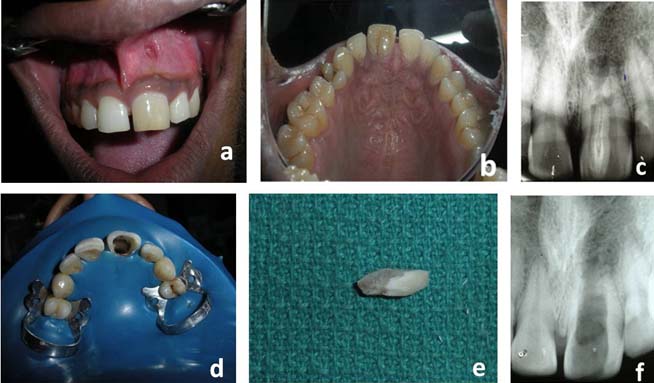

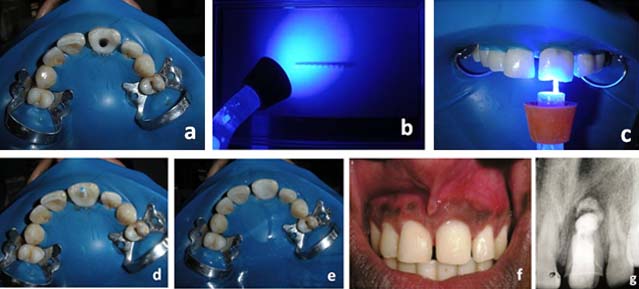

A 22-year-old male patient was referred to Department of Conser-vative Dentistry and Endodontics with a chief complain of pus discharge in upper left teeth region. Clinical examination showed oedema, sinus opening and pus discharge in relation to maxillary left central incisor, which did not respond to thermal tests (heat and cold) but responded positively to palpation and percussion [Table/Fig-1a,b]. On radiographic examination the upper left central incisor showed a bulbous root associated with open apex and periapical radiolucent area. It clearly showed that there was a tooth within a tooth extending nearly up to the root apex [Table/Fig-1c]. A clinical diagnosis of dens in dente Type II with open apex was made. The treatment options were discussed with the patient and informed consent was obtained. The treatment plan consisted of removal of dens in dente followed by root canal treatment, periapical surgery, retrograde filling of root with MTA and bone graft for regeneration of lost periodontal tissue. With rubber dam isolation the dens in dente was carefully separated and removed with help of a diamond bur and ultrasonic tips [Table/Fig-1d-f]. The canal was instrumented circumferentially and enlarged. Chlorhexidine was used as an irrigant as use of sodium hypochlorite carried the risk of extrusion into the periapical region through the open apex. Calcium hydroxide-iodoform paste (Metapex) was used as intra-canal medicament and the canal was obturated with gutta-percha cones after seven days when the patient was asymptomatic. Rest of canal was laterally condensed using accessory cones, and the access cavity was sealed with non-eugenol temporary cement (Cavit, 3M ESPE). After this under local anaesthesia, a mucoperiosteal flap was reflected and severe osseous destruction was observed on facial surface of tooth #21 [Table/Fig-2a]. After thorough debridement of the periapical osseous defect, a canal template was placed inside the canal and the defect was repaired with Resin Modified Glass Ionomer Cement [Table/Fig-2b]. Apex was sealed with MTA (ProRoot MTA, Dentsply) and the large osseous defect was filled with hydroxyapatite bone graft (G-bone, Surgiwear) covering the defect surface [Table/Fig-2c]. Flap was repositioned and sutured with 3-0 silk non-resorbable interrupted sutures [Table/Fig-2d]. Written post-operative instructions were given, antibiotics and analgesics were prescribed for one week. Patient was monitored on weekly schedule post-operatively, to ensure good oral hygiene. Sutures were removed after 10 days and tooth was restored with fiber post and nano-hybrid composite (Coltene Whaledent) [Table/Fig-3a-3e]. Oral hygiene instructions were reinforced, and patient was kept on maintenance for 3 months to re-evaluate this area. At subsequent follow-up examinations tooth was asymptomatic and post-operative radiograph after one year revealed complete healing in peri-radicular region [Table/Fig-3f,g].

(a) Pre-operative; (b) Pre-operative (Palatal view); (c) Pre-operative IOPAR; (d) After removal of dens in dente; (e) Extracted tooth; (f) IOPAR after extraction.

(a) Osseous defect in relation to tooth# 21; (b) Root build up with resin modified GIC; (c) Bone graft placed; (d) Sutures placed.

(a) Crown build-up with composite; (b) Fiber post; (c) Curing of fiber post; (d) Fiber post placed; (e) After crown build-up with composite (Palatal view); (f) Post-operative (after 1year); (g) Follow-up IOPAR (after 1 year).

Discussion

Dental anomalies can cause aesthetic and periodontal problems. Dens in dente is one of the developmental anomaly which was first described in a human tooth by a dentist named Socrates in 1856 [1]. Busch in 1897 suggested ‘dens in dente’ implies the radiographic appearance of “tooth within a tooth” [2]. Hunter suggested the term “dilated composite odontome” [3]. Synonyms for this anomaly are dens invaginatus, invaginated odontome, dilated gestantodontome, dilated composite odontome, tooth inclusion, dentoid in dente. It ranges from a deep fissure or pit on the lingual surface of an anterior tooth and an occlusal pit on the posterior teeth to a broad tract visually or radiographically apparent in dilated teeth. Radiographic examination is the most reliable way to diagnose such anomalies with significant possibility of pulpal involvement and pulpitis. Root canal treatment of such teeth is difficult because of its complex root canal anatomy and the infected pulpal tissues may remain in inaccessible areas of the canal. The objective of this article is to report a case of dens in dente (Oehlers type II) in a permanent maxillary central incisor with open apex and apical pathosis.

Several theories have been proposed to explain the aetiology of this malformation; it is controversial and still remains unclear. Also genetic factors cannot be excluded [4]. The frequency of dens in dente is more common in permanent maxillary lateral incisors, central incisors and premolars. Various authors have given different classifications for dens invaginatus, based on possible variations in clinical and radiographic appearance but the system described by Oehlers in 1957 appears to be most widely used [5]. Oehlers classified it into three types, depending upon its extent into the crown, root and root apex:

Type 1: The invagination ends as a blind sac within the crown.

Type 2: The invagination extends apically beyond the cemento-enamel junction.

Type 3: The invagination extends beyond the cemento-enamel junction, and a second “apical foramen” is evident.

The treatment modalities of dens in dente ranges from conservative restorative procedures to non-surgical root canal therapy, endodontic surgery, intentional replantation or finally extraction. The invagination in dens in dente allows entry of irritants into an area which is separated from pulpal tissues only by a thin layer of enamel and dentin and predisposes it for development of infection. Thus, without any history of caries, or trauma, irritants and microorganisms from oral cavity can cause inflammation [6]. Clinically, if one tooth is affected, contra-lateral tooth should also be examined. In this case, a careful removal of dens in dente was done followed by surgical enododontic treatment, with MTA for apexification of blunderbuss apex. Separation and removal of the least desirable portion is indicated as long as there is a satisfactory crown-to-root ratio for retained part of tooth. Thus, a thorough understanding and the interpretation of clinical findings is essential for dispensing treatment at the correct time, as dens in dente may result in periradicular pathosis.

[1]. Hulsmann M, Dens invaginatus: Aetiology, classification, prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment considerationsInt Endod J 1997 30:79-90. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Alani A, Bishop K, Densinvaginatus. Part 1: Classification, prevalence and aetiologyInt Endod J 2008 41:1123-36. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Hunter HA, Dilated composite odontomeOral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1951 4:668-73. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Hosey MT, Bedi R, Multiple dens invaginatus in two brothersEndod Dent Traumatol 1996 12:44-47. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Oehlers FA, Dens invaginatus (dilated composite odontome). I. Variations of the invagination process and associated anterior crown formsOral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1957 10:1204-18. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Rani N, Sroa RB, Non-surgical endodontic management of dens invaginatus with open apex: A case reportJ Conserv Dent 2015 18:492-95. [Google Scholar]