Introduction

Oral contraceptives are one of the risk factors for gingival disease. Oral contraceptives can affect the proliferation of cell, growth and differentiation of tissues in the periodontium. Nowadays recent research has suggested that the newer generation oral contraceptives have less influence on gingival diseases.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to systematically review the effect of oral contraceptives on periodontium.

Materials and Methods

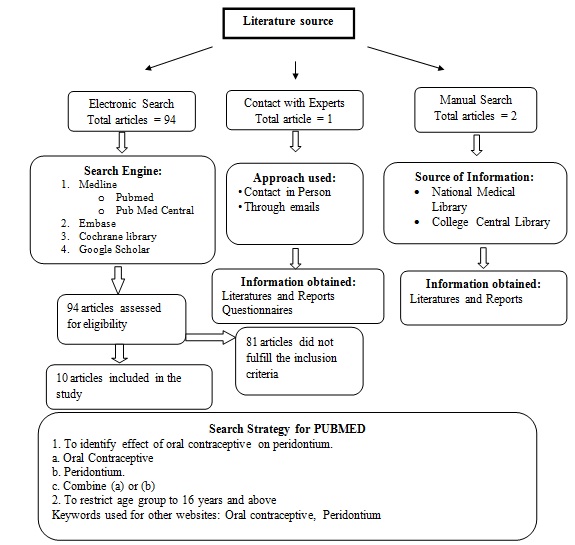

A literature review was performed; PubMed, PubMed Central and Cochrane Library, Embase, Google Scholar were searched from 1970 up to December 2015 to identify appropriate studies.

Results

Out of the total 94 titles appeared 13 articles fulfilled the criteria and were selected for the review. Two articles which were hand searched and one article which was through e-mail was also included. The hormones progesterone and estrogen have direct impact on immune system of the body and thus, affect the pattern and rate of collagen production in the gingiva. Furthermore, the review also shows that longer duration usage of oral contraceptive could lead to poorer oral hygiene status, gingival inflammation and increased susceptibility to periodontal disease.

Conclusion

There are relatively few studies evaluating the effect of oral contraceptives on periodontium. It was found that oral contraceptives have a marked effect on periodontium. The gingival changes after use of oral contraceptives are pronounced in the first few months and with the passage of time these changes get enhanced.

Dental plaque, Gingivitis, Periodontitis, Periodontium

Introduction

Description of the condition: Alveolar bone, gingiva, periodontal ligament and root cementum constitute the periodontium and the study of periodontium both in health and disease is called periodontology [1]. Saini R et al., in 2010 described periodontitis as most common disease of the oral cavity and has described it as inflammatory disease of supporting tissues of teeth, he further described the aetiological aspect of various group of microorganism and specific colonies of bacteria which result in progressive destruction of alveolar bone and the periodontal ligament along with periodontal pocket formation, gingival recession, or both [2]. Research has demonstrated that the host response to perioidontium results in local production of prostaglandins and interleukins which result in inflammation of periodontium [2].

Description of the intervention: Combined Oral Contraceptive (COC) is composed of estrogen and progestogen. The first COC was introduced in 1957 in the United States for the treatment of menstrual disturbances [3]. The mechanism of action of oral contraceptive is that they affect the ovulation by disturbing the function of progestin and estrogen. The progestin acts by suppressing the release of Luteinizing Hormone (LH) from the anterior pituitary gland. It also creates thick cervical mucus and thus, slows the sperm transport and hence, inhibits capacitation (activation of enzymes that permit the sperm to penetrate the ovum). Estrogen diminishes the release of Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) and LH and hence, results in inhibition of ovulation. It has been found that estrogen alters secretion within uterus resulting in patches of edema with dense cellularity, making implantation less likely. Nowadays oral contraceptives are used for pregnancy prevention, treatment of menstrual irregularities and endometriosis [4].

How the intervention might work: The frequent use of oral contraceptives by females influences periodontal disease. The association between the oral contraceptives and gingival inflammation in relation to high concentration of sex hormones was first described by Lindhe and Bjorn in 1967 [5]. Similar investigations linked the use of oral contraceptives to gingival inflammation and periodontal attachment loss. However, these studies date back to more than 25 years when there was a trend towards the use of high dose contraceptive [6].

In the present scenario, when the dose regimen of the oral contraceptives has shifted to low, the evidence of their effect on the periodontium is inconclusive. While the prospective 21 day experimental gingival study concluded by Preshaw PM et al., in 2001 states that the oral contraceptives did not increase the gingival inflammation [7] but the findings of Mullaly BH et al., [8] and Tilakratene A et al., [9] are contrary to these results. Mullaly BH et al., [8] has described that the use of oral contraceptive results in attachment loss, severe probing depth and gingival inflammation in women which are on oral contraceptives. In the study conducted by Tilakratne A et al., [9] among the rural Srilankan females, the mean gingival index scores were higher among females using oral contraceptives for two years and periodontal breakdown was more severe in the females using contraceptives for the duration of 2-4 years.

The use of oral contraceptives increases the levels of female sex hormones present in the sub-gingival environment which could lead to periodontal disease. It has been found that females using oral contraceptives have greater tendency for gingival bleeding, loss of attachment and greater periodontal pocket depth due to increased cellularity and increase in gingival cervicular fluid, along with increase in Prevotella species and almost 16 times increase in Bacteroides species level than normal gingival flora [10].

A number of changes in the periodontal health have been associated with the shift in sex hormones that occur during puberty, menstruation and pregnancy. The advent of contraceptive medication created an interest in their effect on oral tissues [11].

WHY IS IT IMPORTANT TO CARRY OUT THIS REVIEW

The inconclusive and contrasting nature of evidence regarding the effect of low dose oral contraceptive on the perioidontium among the females of child bearing age warrants the need for further investigation into the topic of study. Hence, the present systematic review was carried out to assess the effect of present day oral contraceptives on the periodontal and gingival health among females of child bearing age.

Research Question: To review the effect of oral contraceptives on the perioidontium.

Objective: To estimate periodontal disease risk associated with COC use compared with non-users.

Materials and Methods

Eligibility Criteria: The articles which were published in English, dated from the year 1970 to 2015 were included in this review. The search terms for articles were the terms either in the title or abstract. Full text original research articles were taken. Unpublished articles in press and personal communications were excluded. Our focus was to be broad in scope to include as much relevant existing data as reasonably possible.

Inclusion Criteria:

Original research articles.

The articles emphasizing on the effect of oral contraceptives on periodontal disease.

Exclusion Criteria:

Review articles

Case series, Cases reports and Letters to the Editors

Articles whose abstract are only readable

Types of outcome measures: Change in the periodontal disease indicators as measured by Plaque Index (Silness and Loe 1964), Gingival Index (Loe and Sillness 1963), Sulcular Bleeding Index (SBI), pocket probing depth and clinical attachment level are the primary outcomes measured.

Search method for identification of studies: For the identification of the studies included in this review, we devised the search strategy for each database. The search strategy used a combination of controlled vocabulary and free text terms. The main database was PubMed, PubMed Central, Cochrane Review, Embase and Google Scholar [Table/Fig-1]

Electronic Searches:

PubMed (1970-2015)

PubMed Central (1970-2015)

Cochrane Review (1970-2015)

Embase (1970-2015)

Google Scholar (1970-2015)

Other Sources: The search also included the hand search of the journals fulfilling the inclusion criteria for the review.

Results

A total of 13 studies were included to analyze the effects of oral contraceptives on the periodontium.

The summary of the results has been provided in [Table/Fig-2].

| Study | Sample size | Patient age group | Duration of Treatment | Type of study (Case/Control) | Results | Conclusion |

|---|

| Knight GM and Wade AB (1974) [12] | 171 | 17-23 years | 1.5 years | Two groups: 89 taking hormonal contraceptive and 72 using other form of contraceptive acting as control. | Plaque accumulation (0.81±0.08) and gingival score (0.75±0.05) is more in control group (0.76±0.07) and (0.70±0.05) than in hormonal group but the difference was not significant (p>0.05) | Study demonstrates no significant difference in plaque and gingivitis level between group taking oral contraceptive and comparable group but those receiving oral contraceptive for more than 1.5 years exhibited greater periodontal destruction than those of comparable age in the control group. |

| Kalkwarf K L (1978) [5] | 168 | 18-35 years | 36 months | Two groups: experimental group (n=93) control group (n=75) | The group currently taking oral contraceptives possessed a higher Gingival Inflammatory Index (p<0.001). but Lower Oral Debris Index (p<0.04). Mean gingival index and debris index of oral contraceptive user and non-user are 1.49 (0.04), 0.81 (0.10) and 1.20 (0.05), 0.95 (0.04) | Group currently taking oral contraceptives had a higher mean Gingival Inflammatory Index and a lower mean Oral Debris Index than the control group. |

| Tilakaratne A (2000) [9] | 88 | 17-36 years | 2-4 years | 32 women using hormonal contraceptives for less than 2 years, 17 for 2–4 years and a matched control group of 39 non-users were selected for the study | Contraceptive users had a significantly higher level of gingival inflammation, compared to the non-users | Usage of contraceptive preparations containing estrogen and progesterone resulted in hormonal changes similar to those seen in pregnancy, associated with increased prevalence of gingivitis. There was significantly higher attachment loss with prolonged usage of hormonal contraceptives, compared with controls. |

| Preshaw PM et al., (2001) [7] | 30 | 20-45 years | 3 weeks | Two groups - experimental group (n=14), control group (n=16) | Statistically significant increase in plaque and gingivitis scores were noted in test quadrants (p<0.001) but not in control quadrants (p>0.05) | Current oral contrceptive formulations do not affect the inflammatory response of the gingiva to dental plaque. |

| Mullally BH et al., (2007) [8] | 50 | 20-35 years | 2 years | 8 (16%) of the 50 women no previous medication, 21 referrals (42%) were taking the contraceptive pill and the remaining 21 (42%) had used oral contraceptives previously, but not within a 2-year period before their periodontal examination | Current pill users had deeper mean probing depths and more severe attachment loss compared to non-users. Pill users had more sites with bleeding on probing (44.0% versus 31.1%; p=0.017) | Female patients who were on oral contraceptives tended to have higher plaque levels, more extensive gingival bleeding, deeper periodontal pocketing, and more extensive and severe periodontal attachment loss than those who were not taking the pill |

| Ardakani AH et al., (2010) [13] | 70 | 17-35 years | 2 years | Two groups: experimental group (n=35) control group (n=35) | Oral contraceptive users had higher gingival inflammation and bleeding on probing as compared to non-users. The mean gingival index, plaque index, bleeding on probing of oral contraceptive user and non user are (2.1±0.44, 1.47±0.23, 63.85±13.91 and 2.12±0.42, 1.07±0.20, 37.82±12.81 respectively) p<0.0001 | Women on low dose oral contraceptive pills for at least two years had more extensive gingivitis and gingival bleeding than their matched control |

| Vijay G (2010) [14] | 65 | 20-35 years | Group I (6 month to 1.5 years) 18 subject Group II (1.5 years to less than 5 years) Group III (more than 5 years) 4 subjects | Two groups - experimental group (n=43) Group I 18, Group II 21, Group III 4 and Control group (n=22) | The quantity of plaque and status of periodontal disease was higher in patients on oral contraceptives than in control group. Control group showed a mean plaque index of 1.0725±0.5168, while Group I, II, and III showed mean plaque index of 2.123±0.3967, 2.892±0.3550, and 3.115±0.1816 respectively | Oral contraceptive therapy especially of longer duration could lead to poorer oral hygiene status and increased susceptibility to periodontal disease |

| Brusca MI et al., (2010) [15] | 92 | 19-40 years | March 2007 to February 2009 | Two groups - experimental group (n=41) control group (n=51) | Oral contraceptive users had deeper probing depths (≥5mm) than non-users. Moreover, Oral contraceptive users had higher gingival index scores and clinical attachment loss, ≥2 and ≥5mm, respectively, than non-users (p <0.01) | OC use may increase the risk of severe periodontitis and seems to cause a selection of certain Candida species in periodontal pockets. Oral contraceptive users showed a higher prevalence of P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, and A. actinomycetemcomitans compared to non-users |

| Sambashivaih S et al., (2010) [11] | 100 | 19-40 years | 23 subjects (≤ 12 months) 20 subjects (13–24 months), 6 subjects (25–36 months) and 1 subject (36 months) | Two groups: experimental group (n=50) control group (n=50) | The gingival index and plaque index of contraceptive users was increased as the duration of oral contraceptive increased, 23 subjects using oral contraceptives for ≤ 12 months showed mean gingival and plaque index of (1.409,1.348); 20 subjects for 13–24 months (1.765 and 1.665), 6 subjects for 25–36 months (1.8676 and 1.683) and 1 subject for >36 months gingival and plaque index of (3 and 2.4) respectively. | Current oral contraceptive formulations may have an effect of exaggerating the inflammation of the gingival tissues. |

| Domingues RS et al., (2012) [10] | 50 | 19-35 years | 1 year | Two groups: experimental group (n=25) control group (n=25) | The test group showed increased probing depth (2.228±0.011 x 2.154±0.012; p<0.0001) and sulcular bleeding index (0.229±0.006 x 0.148±0.005, p<0.0001) than controls. No significant differences between groups were found in clinical attachment level (0.435±0.01 x 0.412±0.01; p=0.11). The control group showed greater plaque index than the test group (0.206±0.007 x 0.303±0.008; p<0.0001). | Currently available COC might influence the periodontal condition of women taking these medications for at least 12 months continuously, regardless of age and amount of plaque accumulation, resulting in increased PD and SBI and a slight tendency to develop loss of attachment. |

| Farhad SZ et al., (2014) [16] | 60 | 17-40 years | ---- | Two groups - experimental group (n=35) control group (n=25) | Mean bleeding on probing, probing pocket depths, plaque indexes and clinical attachment losses in the case and control groups are (41.11,3.7832.40, 1.87 and 135.04,15.64, 29.24, 0.24) respectively statistically significant differences in probing pocket depths (p<0.05) and clinical attachment losses between the case and control groups (p<0.05) but no statistically significant differences were found between the plaque index of the case and control groups (p>0.05) | Oral contraceptives affect the periodontal health status of patients and lead to more gingival inflammation |

| Abd-Ali EH, Shaker N T (2013) [4] | 80 | 16-40 Years | 8 months | Two groups - experimental group (n=40) control group (n=40) | Gingival index was significantly higher among oral contraceptive users than non-users which was correlated with the duration of usage (r=0.50) | The gingival changes are seen in the first few months after starting the contraceptive and its severity increased with time. Once the woman discontinues the contraceptive, the gingival condition will reverse. |

| Arumugam M et al., (2015) [17] | 82 | 19-45 years | 1 year | Two groups - Group I-Hormonal contraceptive (HC) users with chronic periodontitis (41) Group II-Female patients with chronic periodontitis (41) | Among the hormonal contraceptive user group and the non-user group, the prevalence of Candida species in periodontal pockets was 26.8% and 29.3% respectively. Mean plaque index, Mean gingival index, Mean probing depth and Mean CAL among hormonal contraceptive users and among non-users were (1.73±0.44, 1.76±0.44, 5.47±1.05 mm and 5.03±1.51 mm respectively) and (1.75±0.47, 1.76±0.46, 5.74±1.14 mm and 5.50±1.55) respectively. It was found to be statistically non-significant (p>0.05). | C. albicans was the most common Candida species isolated from both groups, followed by Candidadubliniensis, Candida krusei, Candidatropicalis, Candida glabrata and Candidaparapsilois |

Risk of bias in included studies: All 13 studies conducted were at low risk [4,5,7–17] for selective outcome reporting. Based on 13 studies, 11 studies conducted were at risk [4,7–11,13–16] and three studies were at low risk for random sequence generation [4,5,11], the two studies conducted were at high risk for incomplete outcome data [5,17]; only one study conducted was at low risk for allocation concealment [12]; the two studies conducted were at low risk for blinding of outcome assessment [7,10] [Table/Fig-3a,3b].

| Reference | Random sequence generation | Allocation conceal-ment | Blinding of outcome assess-ment | Incomplete outcome data addressed | Selective outcome reporting |

|---|

| Arumugam M et al., (2015) [17] | High risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk |

| Abd-Ali E H, Shaker N T (2013) [4] | Low risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Farhad S Z et al., (2014) [16] | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Domingues R S et al., (2012) [10] | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Sambashivaih S et al., (2010) [11] | Low risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Brusca M I et al., (2010) [15] | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Vijay G (2010)[14] | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Ardakani A H et al., (2010) [13] | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Preshaw P M et al., (2001) [7] | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Tilakaratne A (2000) [9] | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Mullally B H et al., (2007) [8] | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Kalkwarf K L (1978) [5] | Low risk | High risk | High risk | High risk | Low risk |

| Knight G M and Wade A B (1974) [12] | High risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk |

Criteria for risk of bias table.

| Criteria | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data addressed | Selective outcome reporting |

|---|

| Low risk | Referring to a random number table; Using computer random number generator | Participants and investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation: Central allocation (including telephone, web-based and pharmacy-controlled randomization); Sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; Sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. | Blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken. | No missing outcome data; Reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups | The study protocol is available and all of the study’s pre-specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre-specified way; The study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were pre-specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon). |

| High risk | Allocation by judgement of the clinician; Allocation by preference of the participant | Using an open random allocation schedule (e.g., a list of random numbers); Assignment envelopes were used without appropriate safeguards (e.g., if envelopes were unsealed or non-opaque or not sequentially numbered); Alternation or rotation; Date of birth; Case record number; Any other explicitly unconcealed procedure | No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; Blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding. | Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups | Not all of the study’s pre-specified primary outcomes have been reported; One or more primary outcomes is reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g., subscales) that were not pre-specified; One or more reported primary outcomes were not pre-specified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect) |

| Unclear | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement of ‘Low risk’ or ‘High risk’. |

Effects of intervention: The total of 13 studies were included to analyze the effects of oral contraceptives on the periodontium measured in terms of gingival index scores, plaque index, sulcular bleeding index scores, probing depth and clinical attachment loss.

A total of six studies reported increase in the gingival index scores in the contraceptive users as compared to the non–users. Abd-Ali EH et al., in study conducted among 80 Iraqi women reported higher gingival index scores among oral contraceptive users as compared to non-users (p<0.01), which was correlated with the duration of usage (r=0.50) [4]. According to a study conducted by Tilakaratne A et al., in a population of rural Sri-Lankan women, it was found that mean gingival index score of hormonal contraceptive users was significantly higher than those of non-users at less than 2 years and at 2–4 years [9]. Ardakani AH et al., in 2010 found the mean gingival index score for oral contraceptive user and non oral contraceptive user were 1.47±0.23 and 1.07±0.20 (p<0.0001) [13]. Kalkwarf KL in 1978 reported that group currently taking oral contraceptives possessed a higher Gingival Inflammatory Index score of 1.49 (0.04) (p < 0.001) than non users [5]. The duration of the contraceptive use was found to be significantly associated with worsening of gingival parameters as reported by Sambashivaiah S et al., in 2010. Twenty three subjects using oral contraceptives for ≤ 12 months showed mean gingival index of 1.40; 20 subjects for 13–24 month was 1.76; mean gingival index of 1.8676 was seen in six subjects using oral contraceptives for 25–36 months [11]. Only two studies conducted by Arumugam M et al., [17] and Knight GM [12] reported non –significant difference between mean gingival index scores of contraceptive users and non-users.

The SBI scores also increased with the use of oral contraceptives as compared to non-users. The finding was reported in one study conducted by Domingues RS et al., in 2011 who found higher SBI scores in the cases as compared to the controls (0.229±0.006 x 0.148±0.005, p<0.0001) [10].

The probing depth and clinical attachment loss as reported by six studies has been found to be more in oral contraceptive users as compared to the non–users. Domingues RS et al., in 2011 in the study carried out among 50 patients found increased probing depth (2.228 ± 0.011 x 2.154 ± 0.012; p<0.0001) among contraceptive users [10]. In a study by Mullally BH et al., the deeper mean probing depth was found in the oral contraceptive users than non-users (3.3-1.0mm versus 2.7 – 0.5mm). Among pill users, 26% of sites had a probing depth >4mm compared to 13% of sites in non-pill users (p = 0.04) [8]. In a study by Farhad SZ et al., in 2013, the significant difference in the probing pocket depth (3.78) and clinical attachment loss (1.87) was found between the case and control groups (p<0.05) [16]. According to the study conducted by Brusca MI et al., in 2010 it was found that the oral contraceptive users had deeper probing depths (≥5 mm) than non-users and clinical attachment loss ≥5 mm than non-users (p<0.01) [15]. In a study by Ardakani AH et al., in 2010 he found mean pocket depth and attachment loss of oral contraceptive user and non oral contraceptive user are 2.06 ± 0.22, 2.1 ± 0.20 and 1.0004 ± 0.23 and 0.98 ± 0.24 respectively [13]. According to study conducted by Knight GM and Wade AB it was found out that those women who are on oral contraceptive for more than 1.5 years (p<0.05) has greater loss of attachment compared to those who were taking contraceptive for a shorter period [12].

These findings are in contrast with the findings of the study conducted by Arumugam M et al., in 2015, which stated that there was no significant difference in the mean probing depth and mean clinical attachment level between hormonal contraceptive users (5.47±1.05mm) and non-users (5.03±1.51 mm) [10].

The plaque index scores in the oral contraceptives users has also been found to be more as compared to non–users and there was concomitant increase in scores with increased duration of use as reported in three studies by Sambashivaiah S et al. [11], Preshaw PM et al., [7] and Vijay G [14]. However, the evidence is still unclear with non–significant difference in plaque scores between users and non-users reported by Arumugam M et al., in 2015 [17], Farhad SZ et al., [16] and Mullally BH et al., [8]. The two studies carried out by Domingues RS et al., [10] and Knight GM [12] reported contradictory findings with higher plaque index scores in the control group (Non-Oral Contraceptives Users) as compared to oral contraceptive users although the difference was statistically non–significant.

Discussion

Summary of main results: Oral contraceptive contains progesterone and estrogen. High level of progesterone increases the blood flow to the gum tissue and causes gums to be more sensitive and vulnerable to irritation and swelling. Vasodilatation and increased capillary permeability is caused by the additive effect of estrogen and progesterone which further leads to increased migration of fluid and white blood cell out of blood vessels. The change in progesterone and estrogen levels affects the immune system as well as the collagen production in the gingiva. Both of these conditions reduce the body’s ability to repair and maintain gingival tissues. Women using oral contraceptives have higher prevalence of Streptococci mutans in their oral cavity as well as higher incidence of dental caries [4].

Due to high levels of estrogen and progesterone individuals on oral contraceptives have conditions similar to pregnant women. Due to presence of estrogen and progesterone in oral contraceptives, the women on these drugs simulate the features of gingivo-periodontitis as that of pregnant women but usually these changes in oral contraceptive using women are seen after long duration of oral contraceptive therapy. Here, the local hygiene factors also have a major role in establishing periodontitis [15].

Oral contraceptive users have an increased risk of severe periodontitis and seems to be a cause for the development of certain Candida species like C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, C. tropicalis, and C. glabrata subgingivally. Moreover, oral contraceptive users also showed a higher prevalence of P. gingivalis, P. intermedia, and A. actinomycetemcomitans as compared to non-users [16].

Agreements and disagreements with other studies: The present review revealed an increased effect on periodontium with the use of oral contraceptive. Kalkwarf KL et al., in 1978 found that patient on oral contraceptives show increased inflammatory response as compared to normal. There usage cause elevated level of progesterone body which changes the vascular structure with increase in micro-vascular permeability in gingival tissue along with increase in number of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and also the production of local mediators like prostaglandin E2 in gingival tissues [5]. Since 1970s (when most of the reports documenting untoward gingival effects associated with oral contraceptive usage were published), it has become evident that many of the side-effects elicited by oral contraceptives are dose-dependent (Williams and Stancel, 1996) [18]. This realization led to the development of current low-dose oral contraceptive formulations. Current oral contraceptives consist of low doses of estrogens (0.05mg/day) and progestins (1.5mg/day). However, the initial formulations contained higher concentrations of sex hormones (20-50μg estrogen and 0.15-4mg progesterone) which have great influence on periodontium [15].

Similarly Sambashivaiah S et al., conducted study in 2010 on 100 patients and found that there is increase in gingival index and plaque index of contraceptive users as the duration of oral contraceptive increased [11]. Domingues RS et al., in 2011 observed in a scientific study that oral contraceptive irrespective of local hygienic factor of gingiva have a great influence on gingival health resulting in gingivo periodontal disease [10].

Recommendations

Proper periodontal assessment and treatment is needed for the women who use oral contraceptives due to its effects in alteration of hormone which affects periodontium.

The negative influence of the changes in estrogen and progesterone levels can be controlled by additional plaque control.

Oral health examination should be an essential part to be followed up routinely to avoid any future dental complications for oral contraceptive users.

Conclusion

It has been unanimously observed and agreed that use of oral contraceptives cause gingivitis as well as peridontitis either by increase of local microorganism like P. gingivalis, P. intermedia and A. actinomycetemcomitans or Candida species or by altering host response. These changes usually appear after few months of oral contraceptive therapy and gradually increase with increase in dosage and duration of therapy. Local factors also play a vital role in patient using oral contraceptives. So strict oral hygiene measures should be taken by female using oral contraceptives to prevent or diminish the intensity of gingivo-periodontitis.

[1]. Dentino A, Lee S, Mailhot J, Hefti AF, Principles of periodontologyPeriodontol 2000 2013 61(1):16-53. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Saini R, Saini S, Sharma S, Oral contraceptives alter oral healthAnn Saudi Med 2010 30(3):243 [Google Scholar]

[3]. Mouton A, Non-contraceptive effects and uses of hormonal contraceptionS Afr Fam Pract 2007 49(7):32-33. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Abd-Ali EH, Shaker NT, The effect of oral contraceptive on the oral health with the evaluation of Salivary IgA and Streptococcus mutans in some Iraqi womenMarietta Daily J 2013 10(1):52-63. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Kalkwarf KL, Effect of oral contraceptive therapy on gingival inflammation in humansJ Periodontol 1978 49(11):560-63. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Das AK, Bhowmick S, Dutta AK, Oral contraceptive and periodontal disease: Prevalence and severityJ Indian Dent Assoc 1971 43(8):155-80. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Preshaw PM, Knutsen MA, Mariotti A, Experimental gingivitis in women using oral contraceptivesJ Dent Res 2001 80(11):2011-15. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Mullally BH, Coulter WA, Hutchinson JD, Clarke HA, Current oral contraceptive status and periodontitis in young adultsJ Periodontol 2007 78(6):1031-36. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Tilakaratne A, Soory M, Ranasinghe AW, Corea SM, Ekanayake SL, Silva MD, Effects of hormonal contraceptives on the periodontium, in a population of rural Sri Lankan womenJ Clin Periodontol 2000 27(10):753-57. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Domingues RS, Ferraz BF, Greghi SL, Rezende ML, Passanezi E, Sant Ana AC, Influence of combined oral contraceptives on the periodontal conditionJ Appl Oral Sci 2012 20(2):253-59. [Google Scholar]

[11]. Sambashivaiah S, Rebentish P D, Kulal R, Bilichodmath S, The influence of oral contraceptives on the periodontiumJ Health Sci 2010 1(1):1 [Google Scholar]

[12]. Knight GM, Bryan Wade A, The effects of hormonal contraceptives on the human periodontiumJ Periodontol Res 1974 9(1):18-22. [Google Scholar]

[13]. Haerian-Ardakani A, Moeintaghavi A, Talebi-Ardakani MR, Sohrabi K, Bahmani S, Dargahi M, The association between current low-dose oral contraceptive pills and periodontal health: A matched-case-control studyJ Contemp Dent Pract 2010 11(3):33-40. [Google Scholar]

[14]. Vijay G, Relationship of duration of oral contraceptive therapy on human periodontium-A clinical, radiological and biochemical studyInd J Dent Adv 2010 2(2):168-74. [Google Scholar]

[15]. Brusca MI, Rosa A, Albaina O, Moragues MD, Verdugo F, Pontón J, The impact of oral contraceptives on women’s periodontal health and the subgingival occurrence of aggressive periodontopathogens and Candida speciesJ Periodontol 2010 81(7):1010-18. [Google Scholar]

[16]. Farhad SZ, Esfahanian V, Mafi M, Farkhani N, Ghafari M, Refiei E, Association between oral contraceptive use and interleukin-6 levels and periodontal healthJ Periodontol & Implant Dent 2014 6(1):13 [Google Scholar]

[17]. Arumugam M, Seshan H, Hemanth B, A comparative evaluation of subgingival occurrence of Candida species in periodontal pockets of female patients using hormonal contraceptives and non-users–A clinical and microbiological studyOral Health Dent Manag 2015 14(4):206-11. [Google Scholar]

[18]. Williams CL, Stancel GM, Estrogens and progestinsIn: Goodman & Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. Hardman JG, Limbird LE, editors 1996 New YorkMcGraw-Hill:1411-41. [Google Scholar]