Primary Extracranial Meningioma as a very Rare Cause of Nasal Mass and Epistaxis in an Elderly

Raman Wadhera1, Sharad Hernot2, Madhuri Kaintura3, Sandeep Bhukar4, S Dheeraj5

1 Professor, Department of Ear, Nose and Throat, Pandit Bhagwat Dayal Sharma Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana, India.

2 Senior Resident, Department of Ear, Nose and Throat, Pandit Bhagwat Dayal Sharma Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana, India.

3 Junior Resident, Department of Ear, Nose and Throat, Pandit Bhagwat Dayal Sharma Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana, India.

4 Junior Resident, Department of Ear, Nose and Throat, Pandit Bhagwat Dayal Sharma Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana, India.

5 Junior Resident, Department of Ear, Nose and Throat, Pandit Bhagwat Dayal Sharma Post Graduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Rohtak, Haryana, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Sharad Hernot, Pocket-AP, 115-A, Virat Apartments, Pitampura, Delhi-110034, India.

E-mail: hernots@yahoo.com

Meningioma is known to be an intracranial pathology, but it can also present extracranially. We report a case of a 55-year-old female who presented to the Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) emergency with a complaint of epistaxis for 1 day. There was a 7-8years history of self-resolving intermittent epistaxis. Nasal examination revealed a mass from which biopsy was taken. The specimen showed meningioma on histopathological examination. The mass was excised by ENT surgeons through lateral rhinotomy incision. It was confirmed to be a meningioma by final histopathological examination. The patient was discharged on 10th post-operative day after suture removal under stable condition and was symptom free on regular follow-ups. Worldwide there have been very less number of cases of primary extracranial meningioma causing symptoms of epistaxis, nasal obstruction and a large sinonasal mass in an elderly.

Epistaxis, Meningioma, Nasal obstruction

Case Report

A 55-year-old female presented to the Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) emergency with complaint of epistaxis for 1 day. The patient also gave history of intermittent episodes of nasal bleed and nasal obstruction for last 7-8years during the previous episodes, but in the present episode, bleeding was profuse. Nasal packing was done and patient was admitted for subsequent treatment and management. The pack was removed on the 3rd day. Anterior rhinoscopy revealed a nasal mass in the left nostril which was almost completely filling the nasal cavity, pushing the septum towards right [Table/Fig-1]. Rest of the ENT examination was unremarkable. Contrast Enhanced Computed Tomography (CECT) scan of nose, paranasal sinuses and brain was done which showed a soft tissue density in the left ethmoid sinus; involving septum and medial wall of left orbit and a provisional diagnosis of inverted papilloma or metastasis was given by the radiologist [Table/Fig-2]. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scan of nose, paranasal sinuses and brain was done, which showed that there was an ill-defined mass lesion involving the bilateral nasal cavities, predominantly on the left side. The mass was extending into the bilateral ethmoid sinuses, showing iso-intense signal on T1W and heterogeneously high signal on T2W and Short TI Inversion Recovery (STIR) images. The lesion was seen extending up to bilateral lamina papyracea laterally. Superiorly the lesion was seen extending upto the cribriform plate. On post contrast imaging, intense heterogenous enhancement was seen in the lesion [Table/Fig-3]. There was no intraorbital extension. Brain parenchyma and rest all the structures appeared normal.

Anterior rhinscopy examination showing mass in left nasal cavity.

CECT - Post contrast enhancement.

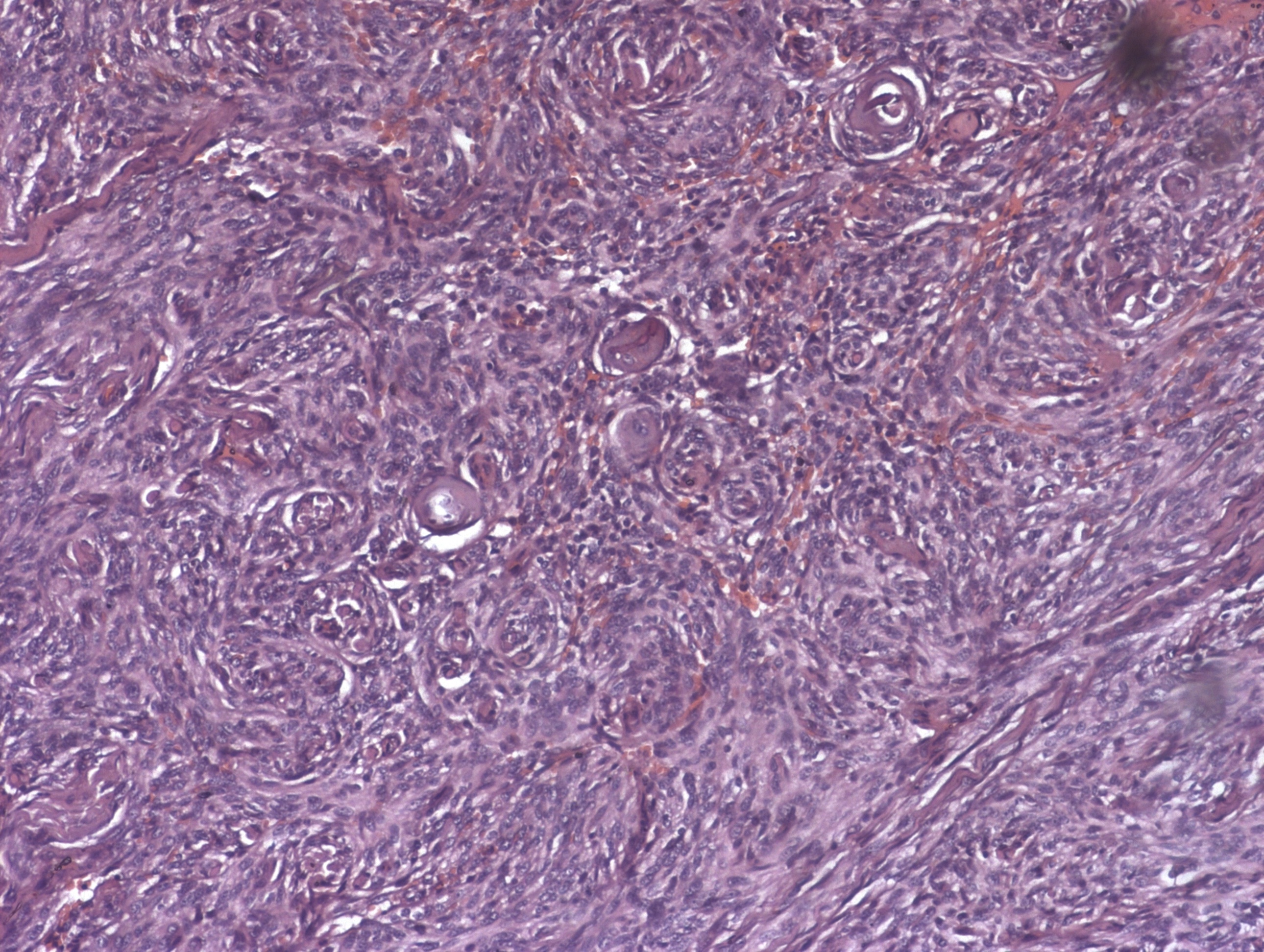

Nasal biopsy was taken under local anaesthesia and sent for histopathological examination, which reported that the specimen had whorled meningoepithelial cells and psammoma bodies, suggestive of nasal meningioma [Table/Fig-4]. On the basis of biopsy and radiological reports, patient was planned to be taken up for nasal mass excision under General Anaesthesia (GA).

Photomicrograph showing whorled meningothelial cells and psammoma bodies (H&E, 40 X).

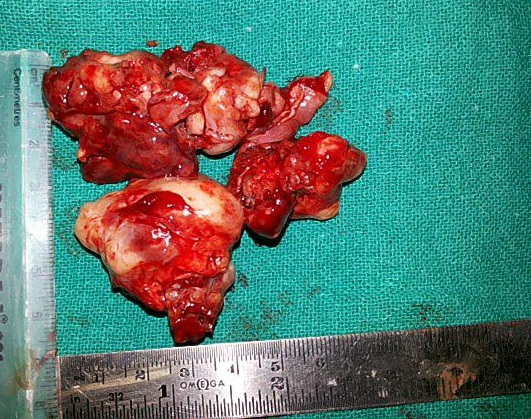

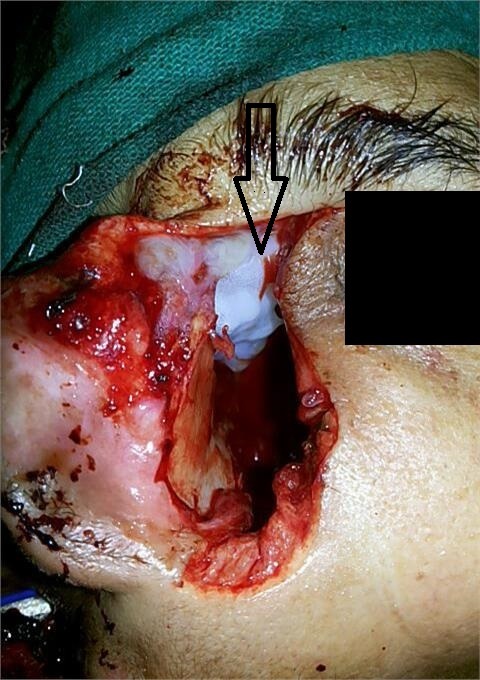

Once GA was induced, lateral rhinotomy incison was made [Table/Fig-5] and the underlying bone was exposed. The frontal process of maxilla was removed to expose the mass. Mass was separated from the surrounding structures and was found to have a superior attachment (i.e., near the cribriform plate). This attachment was cut, mass was taken out and sent for histopathological examination. Excised mass was approximately 7x7 cm in size [Table/Fig-6]. Under microscopic view, the cribriform plate area was assessed for remaining tags and attachment which were either removed or cauterized and few remaining tags and attachment were either removed or cauterized. There was a small breach near the skull base from which dura could be identified. There was no leak of cerebrospind fluid (CSF). The defect was repaired using fascia lata graft, fat and fibrin glue [Table/Fig-7]. Unilateral anterior nasal packing was done and haemostasis was achieved. The incision was stitched in 2 layers. The post-operative period was uneventful and nasal pack was removed after 72 hours.

Lateral Rhinotomy incision.

Excised mass (approximately 7x7 cm in size).

Skull base repair using fascia lata, fat and fibrin glue.

Histopathological examination of excised nasal mass supported the biopsy report and confirmed it as primary extracranial meningioma (nasal origin). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was done of the specimen and was found to be positive for nuclear membrane progesterone receptor and vimentin [Table/Fig-8]. Patient was discharged on 10th post-operative day after suture removal. She was then examined at 2 weekly intervals for 1 month and 4 weekly intervals for next 2 months. She remained symptom free during all her follow-ups [Table/Fig-9].

Photomicrograph showing immunohistochemistry done for specimen and showing positivity for nuclear membrane progesterone receptor (40X).

Patient symptom free on her 6th month of follow-up.

Discussion

Meningiomas account for nearly 10-20% of all the intracranial neoplasms and are the second most common neoplasms of the central nervous system, following gliomas [1,2]. Meningioma is known to be an intracranial pathology, but it can also present extracranially. These extra-cranial meningiomas have been classified into primary and secondary extra-cranial meningiomas. Primary extra-cranial meningiomas are not associated with an intra-cranial mass, whereas secondary extra-cranial meningiomas are extensions from some intra-cranial pathology/disease [3–8]. However, both primary and secondary meningiomas outside the central nervous system are uncommon, but a primary extra-cranial meningioma has a rare occurrence with incidence of 0.9% as compared to incidence of 2% seen in case of secondary meningioma [7]. There are several hypotheses which state that these tumours could arise from the arachnoid cells existing in the nerve sheaths or from ectopic arachnoid cells entrapped extra-cranially, or there is also a possibility that these could arise from pleuripotent mesenchymal cells [9]. A large variety of signs and symptoms are reported in a case of sinonasal meningioma. These clinical features are mainly due to the mass effect of the tumour. The tumour may enter the orbit or nasal cavity through the preformed bony pathways, surgical defects, or foramina of the skull base. There are reports of meningiomas compressing the surrounding tissue without infiltrating it [6,8].

Extracranial meningiomas are classified into 4 groups by the Hoye classification system [10]. This system takes into consideration the chief etiological theories of extracranial meningiomas of the head and neck [Table/Fig-10].

Hoye Classification of extracranial meningiomas [10].

| PRIMARY EXTRACRANIAL MENINGIOMA | SECONDARY EXTRACRANIAL MENINGIOMA |

|---|

| → Extracranial extensions of a meningioma arising in a neural foramen, OR→ Ectopic, without any connection either to foramen of a cranial nerve or to intracranial structures. | → Extracranial extensions of a meningioma with an intracranial origin, OR→ Extracranial metastasis from an intracranial meningioma. |

Radiological investigations like CT scan or MRI give precise information about the extent and invasion of the tumour. Sclerosis or hyperostosis of the surrounding bone is a classical and the most common finding of meningioma. Meningiomas are usually contrast enhancing intracranial extra-dural lesions; however, these tumours may have several different appearances. Kershisnik et al., Swain et al., and Kainuma et al., in their respective case reports have mentioned that on T1-weighed MRI, meningiomas are isointense to the brain, and less commonly they are hypointense. They become isointense (50%) or hyperintense (40%) on T2-weighed MR images. Meningiomas frequently show intense and homogenous enhancement with gadolinium. Enhancement of the thickened adjacent dura, the so called dural tail can also be commonly seen [4–6,8]. However, the final diagnosis of an extra-cranial meningioma is made by histopathological analysis.

In addition, immunohistochemical staining is often necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Meningiomas show immunoreactivity with vimentin and Epithelial Membrane Antigen (EMA) and are focally positive for S-100, keratin and Carcinoembryogenic Antigen (CEA), which helps to distinguish them from other tumours such as poorly differentiated carcinomas, gliomas, melanomas, sarcomas and hemangioblastomas. The treatment of extra-cranial meningiomas is primarily surgical [4–6,8].

Conclusion

A case of primary naso-ethmoidal meningioma in adult can pose a diagnostic dilemma, as it can present with epistaxis and also simulate signs and symptoms of sinusitis, nasal polyp, inverted papilloma, or other sinonasal masses. Radiological investigations (CT and MRI) are important in diagnosing the extent of the disease, and to rule out any intra-cranial extension of the mass, as this would help in diagnosing the meningioma as primary or secondary extra-cranial. Complete surgical removal is the definitive treatment. Histopathological and immunophenotyping examination are required to confirm the pathology.

[1]. Maeng JW, Kim YH, Seo J, Kim SW, Primary extracranial meningioma presenting as a cheek massClin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2013 6(4):266-68. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Mondal D, Jana M, Sur PK, Khan EM, Primary sinonasal meningioma in a childEar Nose Throat J 2015 94(9):7-9. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Daneshi A, Asghari A, Bahramy E, Primary meningioma of the ethmoid sinus: a case reportEar Nose Throat J 2003 82(4):310-11. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Kershisnik M, Callender DL, Batsakis JG, Extracranial, extraspinal meningiomas of head and neckAnn Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1993 102(12):967-70. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Swain RE Jr, Kingdom TT, DelGaudio JM, Muller S, Grist WJ, Meningiomas of the paranasal sinusesAm J Rhinol 2001 15(1):27-30. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Kainuma K, Takumi Y, Uehara T, Usami S, Meningioma of the paranasal sinus: a case reportAuris Nasus Larynx 2007 34(3):397-400. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Batsakis JG, Pathology consultation. Extracranial meningiomasAnn Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1984 93(3):282-83. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Morris KM, Campbell D, Stell PM, Mackenzie I, Miles JB, Meningiomas presenting with paranasal sinus involvementBr J Neurosurg 1990 4(6):511-15. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Rushing EJ, Bouffard JP, Mc Call S, Olsen C, Mena H, Sandbeg GD, Primary extracranial meningiomas: An analysis of 146 casesHead Neck Pathol 2009 3:116-30. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Hoye SJ, Hoar CS, Murray JE, Extracranial Meningioma presenting as a tumor of the neckAm J Surg 1960 100:486-89. [Google Scholar]