Introduction

There are limited studies on consumer behaviour toward counterfeit products and the determining factors that motivate willingness to purchase counterfeit items.

Aim

This study aimed to fill this literature gap through studying differences in individual ethical evaluations of counterfeit drug purchase and whether that ethical evaluation affected by difference in income. It is hypothesized that individuals with lower/higher income make a more/less permissive evaluation of ethical responsibility regarding counterfeit drug purchase.

Materials and Methods

To empirically test the research assumption, a comparison was made between people who live in the low-income country Sudan and people who live in the high-income country Qatar. The study employed a face-to-face structured interview survey methodology to collect data from 1,170 subjects and the Sudanese and Qatari samples were compared using independent t-test at alpha level of 0.05 employing SPSS version 22.0.

Results

Sudanese and Qatari individuals were significantly different on all items. Sudanese individuals scored below 3 for all Awareness of Societal Consequences (ASC) items indicating that they make more permissive evaluation of ethical responsibility regarding counterfeit drug purchase. Both groups shared a basic positive moral agreement regarding subjective norm indicating that influence of income is not evident.

Conclusion

Findings indicate that low-income individuals make more permissive evaluation of ethical responsibility regarding counterfeit drugs purchase when highlighting awareness of societal consequences used as a deterrent tool, while both low and high-income individuals share a basic positive moral agreement when subjective norm dimension is exploited to discourage unethical buying behaviour.

Introduction

Development of effective organizational and technical counter measures for counterfeit drugs requires a thorough understanding for factors affecting both, supply and demand of counterfeit drugs. It is clear that searching for and punishing counterfeiters may not be the most effective course of action as long as there are people who demand counterfeit drugs. Industry, drug regulatory authorities and policy-makers need to understand why some consumers buy counterfeits. In fact, despite counterfeiting has existed long time ago, knowledge about consumer behaviour toward counterfeit products and the influencing factors that motivate willingness to purchase counterfeits is still very limited [1]. This is inspite the fact that consumers remain both the root problem and the ultimate destination of counterfeit products. This had drawn the attention of researchers to the importance of addressing the demand side of the counterfeit product market.

Inappropriate consumer behaviour is one of the most important factors explaining purchase decision of counterfeits and therefore, has been widely explored by marketing scholars. An example of an issue in this area excessively studied is the problem of counterfeiting from the consumer perspective (e.g., Cordell et al., 1996; Bloch et al., 1993; Wee et al., 1995) [2–4], specifically, the ethical attitudes of consumers which have been widely explored in the literature as a key factor influencing the purchase of counterfeit products [2,5]. However, much of the available reseach remains limited to luxurious products with very few (e.g., Leisn and Nill, 2001; Alfadl et al., 2013) [6,7], investigated perceptions of consumers toward counterfeit drugs purchase although consumer demand for counterfeit drugs is an important aspect of consumer behaviour. In addition, although the effect of demographic factors on purchase intention of counterfeits has reported in several studies [8–10] to date the effect of income on ethical/unethical decision of purchase intention of counterfeit drugs has not been examined. This study is addressing this literature gap and attempting to answer the research question of whether distinction in income level between two culturally similar groups make significant difference in their willingness to adopt more/less permissive ethical evaluation with regard to counterfeit drugs purchase.

Many studies documented that people of different demographic characteristics tend to vary in their willingness to purchase counterfeit products [4,11–13]. In consequence, the relationship between income and intention to purchase counterfeit products has been extensively explored. A study conducted in Singapore reported that people from lower income groups held more favourable attitudes towards purchase of pirated CDs [12]. Also, income was reported in another study conducted in China as a moderator of purchase intention of pirated software [13]. However, some studies reported that income had no significant effect on consumers’ intention to purchase counterfeit goods [14–16]. Other scholars went further to state that any demographic difference will not create a variety of purchase behaviour [3].

Hence, it is clear that no general agreement on whether demographic differences, in specific economic status differences, generate variations between groups in adopting more/less ethical behaviour towards counterfeits purchase. To study this, and consequently answer the research question, authors developed ethical scenarios meant to “trigger” respondents’ ethical decision-making process. Awareness of Societal Consequences (ASC) and Subjective Norm (SN) were exploited to develop the scenarios. These two dimensions of attitude were selected because they are often cited as factors that discourage the purchase of counterfeits in developed countries (e.g., Leisn and Nill, 2001) [6,17,18]. However, the ethical evaluation related to ASC and SN is considerably broad and is dependent on a number of other aspects. One of these aspects, which has common acceptance as dominant motivation for consumers to consciously purchase counterfeits, is price or income level. People living in low-income households or located in poor countries are more susceptible to purchase counterfeit drugs especially when the products becoming cheaper [9,19]. The World Health Organization supported this fact and reported that counterfeited drugs are close to 10% of the pharmaceutical market worldwide, of which 25% is located in the poor countries [20].

For empirical examination of the possibility that difference in income level may affect ethical evaluations and consequently, propensity to purchase counterfeit drugs, authors interviewed two groups of people assumed to be similar in various dimensions except income level which is very dissimilar. Those two groups are individuals in Sudan, a poor African country with a developing economy, and individuals in Qatar, a member state of the rich Arab Gulf Cooperation Council (AGCC) with a developed economy [21].

According to the most recent estimate, Sudan had a population of 36,108,853 inhabitants. The majority of the population (92.7%) was younger than 55 years, with generally slightly more males than females. The Sudanese population has a rich diversity of ethnic groups, but dominated by Sudanese Arab (approximately 70%) [21]. On the other hand, Qatar is esitmated to have 2,194,817 inhabitants, of which the majority (95.7%) was younger than 55 years. Qatar is inhibited by more women than men [15]. Regarding economic status, Sudan had a GDP Per Capita (PPP in USD) of 4,300 USD ranking it as the 175th in the world rankings according to GDP Per Capita (PPP), while Qatar had a GDP Per Capita (PPP) of 143,400 USD ranking this country on the 1st place in their world rankings [22].

Materials and Methods

Ethical Consideration

Before starting data collection in Sudan, formal letters and ethics approval were obtained from the Research Directorate of the Federal Ministry of Health. With regard to Qatari sample, ethics application was obtained from Qatar University’s Institutional Review Board. Then, several measures were taken to ensure that no respondent in both countries would be negatively affected due to his participation in the study. Privacy was considered during the consumer survey interviews. Interviewers escorted the respondent, who had verbally consented to be interviewed, to a calm place for the interview. Anonymity was preserved. Participants were assured that data analysis would not be used against them. Interviewers also assured confidentiality. Finally, the participants were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could drop out of the survey at any time.

Study Design

The goal of this study was to understand whether income difference influence consumers’ perception of ethics in the context of counterfeit drugs purchase. Cross-sectional study was conducted where authors collected data using basic survey techniques. They asked the same questions to two groups of individuals in Sudan and Qatar.

Study Population and Sampling

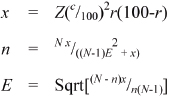

Convenience sampling was used to select the respondents in Sudan and Qatar, although it was tried to weigh the sample to match the general demographics of Sudanese and Qatari populations as closely as possible. A sample of 1003 Sudanese and 167 Qatari individuals was collected. Sample size for respondents in Qatar and Sudan was calculated based on Raosoft® software (http://www.raosoft.com/samplesize.html). The sample size n and margin of error E are given by

It is based on a margin of error of 5-7%, confidence level of 95%, alpha=0.05, population size of approximately of 2 million for Qatar, while 39 million for Sudan [21,22], and an estimated response distribution of 90%. For the Sudanese sample, the minimum sample size should be 385. The eligibility criteria included being Sudanese/Qatari, agreeing to participate, and being 18 years or older. According to the Centre for Economics and Business Research, for this type of research, a sample size of 1,000 is considered robust [23]. Data collection took about two months.

Study Tool

Survey items presenting two scenarios along with moral intention questions were given to participants. To ensure understanding, at the beginning of the interview the scenarios were presented to participants showing that purchasing counterfeit drugs harms the economy, negatively affects the health system, discourages research companies from developing new medicines, and is socially stigmatised.

The questionnaire used in this study was pre-tested and checked for reliability (i.e., 0.862) and content and face validity [24]. Participants were asked to respond to each question on a five-point Likert scale that ranged from 5 = “Strongly Agree” to 1 = “Strongly Disagree”, with 3 = “I don’t know” as the neutral response. The questionnaire used in this study was in Arabic.

Satistical Analysis

Data collected were analysed descriptively using frequency (percentages), and mean (SD). Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was conducted to confirm data normality. Due to the normality of the data, the independent t-test was carried out to compare between the two samples at alpha level of 0.05 using SPSS version 22.0.

Results

The gross domestic product per capita of Sudan was USD 1,753 versus USD 93,714 for Qatar, which is 54 times much higher than Sudan. A 98% response rate was obtained due to the face-to-face survey design. All questionnaires were usable, with no missing data. Participants are consumers in Sudan (n=1003) and Qatar (n=167). Both Sudanese and Qatari respondents were equally distributed between the genders at 47% (472) male and 53% (531) female for Sudanese, while Qatari respondents were 43% (71) male and 57% (95) female (gender was not determined/checked, there is one missing value for the same). The sample tends to be young in age with 53% and 39% of Sudanese and Qatari participants respectively are less than 30 years. Also the sample tends to be educated with most of the Sudanese respondents were university or college graduates (39%), and only a small number had an education level lower than elementary school (7%), while the Qatari respondents were predominantly highly educated at 87% university graduates and only 2% elementary school level.

Means and standard deviations were computed for each item within each group. Following this, differences between the mean of the two groups for each item were tested with independent samples t-test. Items are scored on a 1 to 5 scale, with 1 as most unethical and 5 as most ethical; the midpoint "I do not know" response was scored as 3. Thus, a number above 3 indicates an "ethical" evaluation and a number below 3 an "unethical" evaluation. The results of the analysis are presented in [Table/Fig-1].

Comparison of the results of the responses to the items of the two scenarios.

| Items | Sudanese Consumer | QatariConsumer | p-value |

|---|

| Mean±Std. Dev. | Mean±Std. Dev. |

|---|

| 1. Purchasing non-authentic drugs harm economy of my country | 1.93±1.026 | 3.61±1.023 | <0.001 |

| 2. Purchasing non-authentic drugs undermine national health system | 1.77±0.924 | 3.78±1.013 | <0.001 |

| 3. Purchasing non-authentic drugs discourage manufacturers of legitimate drugs | 2.42±1.163 | 3.43±1.100 | <0.001 |

| 4. Relatives and friends approve decision to buy non-authentic drugs | 3.58±1.192 | 3.29±1.066 | 0.002 |

| 5. Relatives and friends think I should buy non-authentic drugs | 3.50±1.145 | 3.81±0.881 | <0.001 |

Based on the [Table/Fig-1] above, the Qatari consumers were more ethical in all statements except for statement 4. Based on the country income per capita, Qatar, which is 54 times richer than Sudan generally, has consumers that were more ethical.

Discussion

The results of the two independent sample t-test allowed for the testing of the differences in the perceptions of ethical purchase of counterfeit drugs between Sudanese and Qatari samples. In answer to our research question, the findings indicated that attitude of the two groups towards both tested dimensions of ASC and SN, regarding ethicality of counterfeit drugs purchase, differ significantly in all items. Interestingly, while analysis indicates that Sudanese individuals make more permissive evaluation of ethical responsibility regarding counterfeit drug purchase on the dimension of ASC (items 1, 2, and 3), both Qatari and Sudanese individuals share a basic positive moral agreement of what is ethical and unethical (both groups scored above 3.0) on SN dimension (items 4 and 5). What does differ is the magnitude of the ethical evaluation; with Sudanese individuals indicate a more ethical evaluation for the first item in SN (item 4), while Qatari individuals were much less extreme in their ethical evaluation; and the contrary true for the second item measuring SN (item 5). This findings contradict what has been repoted by Wee et al., and Kwong et al., who concluded that no relation between purchase intention and income [4,14]. However, this cantradiction may be, to some extent, due to the type of product being studied. Some scholars suggested that product types may influence counterfeit buying behaviour [4,8]. Products that are considered risky are less likely to be purchased. However, this may be true only when consumers make their purchase decision of counterfeit for saving purposes although they can afford buying the genuine [25,26], but in case of counterfeit pharmaceuticals, it seems that the main motivation for purchasing fake drugs is to find a cheaper alternative for the unaffordable, impossible-to-purchase, legitimate medicine. In other words, poor consumers will have no choice other than the counterfeit because the genuine life-saving medicine is not affordable. These findings also supported by the findings of Tom et al., and Ang et al., who reported that lower income levels do make people to adopt more permissive ethical evaluation towards counterfeit production and sales in general [11,12]. Furthermore, Tom et al., and Albert-Miller do report an effect of price on the intent to purchase counterfeit products [11,27].

According to the findings items one, two and three scored below 3 for Sudanese participants, it is clear that when the prime incentive to go for countefeit drugs is economical, low income groups may not respond well to messages highlighting societal consequences such as the chilling effect of counterfeit drugs purchase on the economy, its tendency to discourage companies from investments in research and developments, undermining the official health system, and other similar messages reported in the literature [4,9]. This may be logical because if a consumer is forced to choose between counterfeit drugs or no medicine at all, discouraging the purchase through highlighting the unethical nature of the decision may not be a viable option. It is mentioned in the literature that the acceptability of purchases of counterfeit goods higher when there was a survival need rather than just wanting to save money [28]. These messages aiming to emphasize the unethical nature of counterfeit drugs purchase decision, as an effort to discourage the behavior, seems to be effective in Qatar (participants scored above 3). Results obtained in this current study that high income groups tend to adopt less permissive ethical evaluation towards counterfiets is supported by another study conducted in the high-income member state AGCC country UAE which reported that ethical judgement is a key factor in consumers’ decision not to purchase counterfeits [29].

In general, it seems that ASC works well in discouraging the unethical purchase decision of counterfiet durgs in high-income countries where counterfeiters targeting the so called life-style drugs (e.g., Viagra) [30], but in low-income countries, for impoverished consumer infected with malaria, for whom purchasing the counterfeit may be the only viable alternative, societal consequences and other similar messages might be the last thing could discourage him from buying the counterfeits.

On the other hand, in the context of this study, income does not seem to have strong effect on the role of subjective norm as an important factor pursuading consumers not to take unethical decision regarding counterfeit drugs purchase (both Sudanese and Qatari scored above 3). Thus, this study gives an indication that negative impact of low income on the role of subjective norm in combating unethical decision regarding purchase of counterfeit drugs is not evident. This finding highlights the importance of subjective norm or peer pressure as a persuassive measure that could discourage unethical purchase decision in low-income communities. Also, this finding is consistent with previous findings on the influence of subjective norm and peer pressure on a consumer’s behaviour [9,27,31]. It is well documented in the litrature that peer rejection of the behaviour serves as a deterrent to the extent that social controls may be an even better deterrent to crime than physical controls because individuals will attempt to avoid exposure if they engage in a behaviour that is not supported by their peers [32,33].

Current finding that societal pressures from family or friends could shift low-income groups toward more ethical purchase decision could be exploited in designing combat strategies. To move those economically constrained consumer not to buy counterfeit drugs, it may be a promising solution to involve their family and friends. The purchasing of counterfeit drugs in low-income countries may be discouraged if potential buyers can be convinced that their families and friends will not support this unethical behaviour. Not only the potential buyers, but also those who are already against the purchase of counterfeit drugs, could be targeted to share the fight against counterfeits. The power they have in influencing their family and friends’ purchase intent could be acknowledged.

Limitation

Even though the study is unique and important especially in this part of the world, it has two limitations. First, the respondents surveyed in both countries were selected conveniently and secondly, was the sample size. Both aspects might cause non-representativeness of the population. Thus, the results are not necessarily could be generalized to the population.

Conclusion

It could be concluded that low-income individuals make more permissive evaluation of ethical responsibility regarding counterfeit drugs purchase when messages highlighting awareness of societal consequences used as a deterrent tool, while both low and high-income individuals share a basic positive moral agreement when subjective norm dimension is exploited to discourage unethical buying behaviour. These findings highlight the importance of subjective norm as a tool to move those economically constrained consumer not to buy counterfeit drugs.

[1]. Eisend M, Guler PS, Explaining counterfeit purchases: a review and previewAcad Mark Sci Rev 2006 10(12):1-25. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Cordell VV, Wongtada N, Kieschnick RL, Counterfeit purchase intentions: role of lawfulness attitudes and product traits as determinantsJ Bus Res 1996 35(1):41-53. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Bloch PH, Bush RF, Campbell L, Consumer “accomplices” in product counterfeiting: a demand side investigationJ Consum Mark 1993 10(4):27-36. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Wee C, Tan S, Cheok K, Non-price determinants of intention to purchase counterfeit goods: an exploratory studyInt Mark Rev 1995 12(6):19-46. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Petty RE, Wegener DT, Fabrigar LR, Attitudes and attitude changeAnnu Rev Psychol 1997 48(1):609-47. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Leisn B, Nill A, Combating product counterfeiting: an investigation into the likely effectiveness of a demand-oriented approach. In: Krishnan R, Viswanathan M, editorsMarketing Theory and Applications 2001 Chicago, Illinois:271-277. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Alfadl AA, Hassali MA, Ibrahim MI, Counterfeit drugs demand: perceptions of policy-makers and community pharmacists in SudanRes Soc Adm Pharm 2013 9(3):302-10. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Wong KK, Yau OHM, Lee JSY, Sin LYM, Tse ACB, The effects of attitudinal and demographic factors on intention to buy pirated cds: the case of Chinese consumersJournal of Business Ethics 2003 47(3):223-35. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Stravinskiene J, Dovaliene Ambrazeviciute R, Factors influencing intent to buy counterfeits of luxury goodsEconomics and Management 2013 18(4):761-68. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Hamelin N, Nwankwo S, El Hadouchi R, Faking brands: consumer responses to counterfeitingJournal of Consumer Behaviour 2013 12:159-70. [Google Scholar]

[11]. Tom G, Garibaldi B, Zeng Y, Pilcher J, Consumer demand for counterfeit goodsPsychol Mark 1998 15(5):405-21. [Google Scholar]

[12]. Ang SH, Cheng PS, Lim EC, Tambyah SK, Spot the difference: consumer responses towards counterfeitsJ Consum Mark 2001 18(3):219-35. [Google Scholar]

[13]. Tan B, Understanding consumer ethical decision making with respect to purchase of pirated softwareJ Consum Mark 2002 19(2):96-111. [Google Scholar]

[14]. Kwong KK, Yau OMH, Lee JSY, Tse ACB, The effect of attitudinal and demographic factors on intention to buy pirated CDs: the case of Chinese consumersJ Bus Ethics 2003 47(3):223-35. [Google Scholar]

[15]. Vida I, Determinants of counsumers willingnes to purchase non-deceptive counterfeit products, Managing Global Transitions 2007 http://www.fmkp.si/zalozba/ISSN/1581-6311/5_253-270.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2015 [Google Scholar]

[16]. Bian X, Moutinho L, An investigation of determinants of counterfeit purchase considerationJ Bus Res 2009 62(3):368-78. [Google Scholar]

[17]. Mir IA, Impact of the word of mouth on consumers’ attitude towards the non-deceptive counterfeitsMiddle-East Journal of Scientific Research 2011 9(1):51-56. [Google Scholar]

[18]. de Matos CA, Ituassu CT, Rossi CAV, Consumer attitudes toward counterfeits: a review and extensionJournal of Consumer Marketing 2007 24(1):36-47. [Google Scholar]

[19]. Franses PH, Lede M, Income, cultural norms and purchases of counterfeits. Econometric Institute Report 2012-26http://repub.eur.nl/pub/37618/EI2012-26.pdf. Accessed May 5, 2016 [Google Scholar]

[20]. World Health Organization (WHO) [homepage on the Internet]. Substandard and counterfeit medicines., Fact sheet No. 275, November, 2003. Available from:. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs275/en/print.html. Accessed November 20, 2015 [Google Scholar]

[21]. The Wold Bank. New Country Classification. http://data.worldbank.org/news/new-country-classifications. Accessed May 5, 2016 [Google Scholar]

[22]. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) [homepage on the Internet]. The world factbook. Available from: http://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/su.html. Accessed November 12, 2015 [Google Scholar]

[23]. Centre for Economics and Business Research (CEBR) [homepage on the Internet]. Counting counterfeits: defining a method to collect, analyse and compare data on counterfeiting and piracy in the single market. Final report for the European Commission Directorate-General single market. [updated 2002]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/internal_market/indprop/docs/piracy/final-report-cebr_en.pdf. Accessed November 20, 2015 [Google Scholar]

[24]. Alfadl AA, Ibrahim MM, Hassali MA, Scale development on consumer behaviour toward counterfeit drugs in a developing country: a quantitative study exploiting the tools of an evolving paradigmBMC Public Health 2013 13:829 [Google Scholar]

[25]. Prendergast G, Chuen LH, Phau I, Understanding consumer demand for non-deceptive pirated brandsMark Intell Plann 2002 20(7):405-16. [Google Scholar]

[26]. Gentry JW, Putrevu S, Shultz CJ, The effects of counterfeiting on consumer searchJ Consum Behav 2006 5(3):245-56. [Google Scholar]

[27]. Albers-Miller ND, Consumer misbehavior: why people buy illicit goodsJ Consum Mark 1999 16(3):273-87. [Google Scholar]

[28]. Casola L, Kemp S, Mackenzie A, Consumer decisions in the black market for stolen or counterfeit goodsJ Econ Psychol 2009 30(2):162-71. [Google Scholar]

[29]. Fernandes C, Analysis of counterfeit fashion purchase behaviour in UAEJournal of Fashion Marketing and Management 2013 17(1):85-97. [Google Scholar]

[30]. Bate R, Making a killing: the deadly implications of the counterfeit drug trade 2008 Washington, D.C.AEI Press [Google Scholar]

[31]. Powers KI, Anglin DM, Couples’ reciprocal patterns in narcotics addiction: a recommendation on treatment strategiesPsychol Market 1996 13(8):769-83. [Google Scholar]

[32]. Barker T, Peer group support for police occupational devianceCriminology 1977 15(3):353-66. [Google Scholar]

[33]. Downes D, Rock P, Understanding Deviance: A Guide to the Sociology of Crime and Rule-Breaking 1982 OxfordClarendon Press [Google Scholar]