Occupational transmission of potentially infectious viruses like HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C is one of the important health hazards to Health Care Workers (HCWs). WHO reported 2.5% of all HIV, 40% of Hepatitis B and 40% of Hepatitis C infections due to occupational transmission [1]. Following guidelines for standard precautions (earlier known as universal precautions) plays an important role in minimizing incidences of occupational exposures; effective PEP helps in reducing chances of transmission if exposure has already occurred. Various guidelines from national [2] and international bodies [3,4] are available for effective PEP. Yet, various studies reported from India and other countries have observed poor awareness about PEP for HIV [5–15] as well as about PEP for Hepatitis B [16–19] among various categories of HCWs.

Our primary objective was to study details of regimen used, tolerance and efficacy of PEP for HIV and Hepatitis B; from the reported incidences over the period of thirteen years. Secondary objective was to study timing of initiation of PEP therapy for HIV after the exposure as well as status of Hepatitis B vaccination and anti-HBS antibody titre among HCWs exposed to Hepatitis B.

We believe observations of this study, will be useful not only to HCWs in increasing their awareness about PEP but also to administrators of the health care settings as well as to bodies like Hospital Infection Control Committee (HICC) in forming their policies, especially of developing and resource limited countries like India.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting: This was a retrospective observational study. It was done at Shree Krishna Hospital; which is a 550 bed rural based tertiary care teaching hospital, situated in Western India.

Sample Size, Sampling Technique, Study Duration and Study Population

HICC of our institute started maintaining records of all incidences of accidental exposures reported to designated physician since 2003. Our study included details of all reported incidences of occupational exposures to HIV and Hepatitis B positive sources occurred to HCWs between period from 1st January 2003 to 31st December 2015. Ninety six such incidences were reported during this period. There were no exclusion criteria. HICC permission was taken for academic use of the data. Human Research Ethics Committee approval was taken. This being a retrospective study, waiver of consent was considered by Ethics Committee. Confidentiality of source patients and exposed HCWs was maintained at all levels.

Data Collection: To manage the case of accidental exposure, HICC had developed protocol for the institute, which was largely based on the guidelines given by National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) of India [2,29] and Centre for Disease and Control, (CDC), USA [3,30]. In the situation of exposure to HIV or Hepatitis B positive source; designated physician decided the need for PEP, baseline HIV, HBsAg and other laboratory testing and also provided counselling to all exposed HCWs after an accidental exposure. Selection of basic or expanded regimen for PEP for HIV was also decided by designated physician; which was based on guidelines given by NACO of India [2,29] and CDC [3,30]. Written consent was taken before testing the source patient for assessing his/her HIV status. Written consent was also obtained from the HCWs exposed to HIV positive source, for testing his/her HIV status as well as for PEP therapy whenever indicated. In the situation of exposure to HIV, repeat testing for HIV of exposed HCW was done at six weeks, three months and six months. In the case of exposure to Hepatitis B, HCW’s baseline HBsAg screening was done. History of vaccination against Hepatitis B was taken. In the situation of completed all three doses of vaccine (at zero, one and six months) or incomplete vaccination; HCW’s anti-HBS antibody titre was also tested. In the case of non-vaccination or titre is less than 10 mIU/ml, stat dose of vaccine was given. Option of Hepatitis B immunoglobulin was also provided to the HCW if he/she was financially viable. If titre was between 10-100 mIU/ml, booster dose of vaccine was given and vaccination was completed as per schedule if not completed earlier. For titre >100 mIU/ml no immediate action was taken. Repeat testing for Hepatitis B transmission was done at three months and six months for all exposures to Hepatitis B as per guidelines from NACO of India [2,29] and CDC [3].

HICC had maintained record of category of HCW, mode of exposure as well as details of PEP whenever indicated. This detail was comprised of baseline HIV status, PEP for HIV indicated or not, reasons for not giving PEP therapy whenever applicable, time of initiation of PEP for HIV after the exposure, regimens used, side effects observed, PEP completed or not and follow-up results of HIV testing for all exposures to HIV. For exposures to Hepatitis B, HICC record had detail of baseline HBsAg status, Hepatitis B vaccination status, anti-HBS antibody titre, PEP for Hepatitis B given as well as results of HBsAg on follow-up. For our study, information was collected about category of exposed HCW, mode of exposure and about PEP for all 96 incidences of exposure to source positive for HIV and/or Hepatitis B. Missing information was mentioned as ‘details not available’. Descriptive analysis was done of collected data in the form of frequencies and percentage.

Results

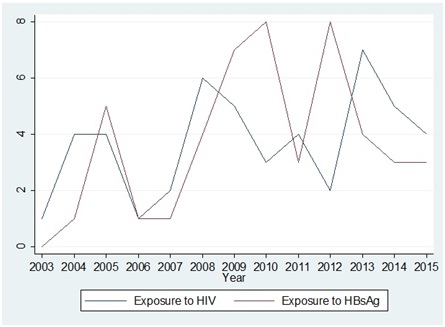

Total incidence of exposure to HIV was 48 (Male:19, Female:29, M:F ratio was 1:1.5) and to Hepatitis B was 48 (Male:20, female: 28, M:F ratio was 1:1.4) between the year 2003 to 2015. There were two incidences of co-exposures to HIV and Hepatitis B both. Number of reporting and trend of year wise reporting is shown in [Table/Fig-1]. Of the total 96 exposures, 31 (32.3%) exposures were reported in the first half of the study period (from 1st January 2003 to 30th June 2009, six and half years) against 65 (67.7%) in the latter half of the study period (from 1st July 2009 to 31st December 2015, six and half years)

Category of HCWs exposed is mentioned in [Table/Fig-2]. Circumstances during which exposure occurred to all 48 HCWs are described in [Table/Fig-3]. Of the 48 exposures to HIV, PEP was warranted among 39 exposures. Details of reasons for not prescribing PEP therapy in remaining nine incidences is also described in [Table/Fig-3]. Baseline HIV testing of these HCWs done in 45 cases was found to be negative; one HCW refused for the same and details were not available for other two incidences.

Trend of reporting of incidences between the year 2003 to year 2015.

Category of HCWs exposed to HIV and Hepatitis B.

| Category of HCW | Exposed to HIV | Exposed to Hepatitis B | Total 96 (%) |

|---|

| Nursing staff | 17 | 20 | 37 (38.6) |

| Postgraduate students | 12 | 11 | 23 (24.0) |

| Consultants | 6 | 6 | 12 (12.5) |

| MBBS Interns | 5 | 5 | 10 (10.4) |

| Servant/Attendants | 4 | 2 | 6 (6.2) |

| Technicians | 3 | 2 | 5 (5.2) |

| Nursing students | 1 | 2 | 3 (3.1) |

| Total | 48 | 48 | 96 |

HCW- Health Care Worker

Circumstances of exposures to HIV positive source, type of PEP regimens used and reasons for not giving PEP in remaining HCWs:

| Circumstances of exposure | Type of PEP regimen used | Numbers in whom PEP not given | Reason for which PEP was not given in remaining HCWs | Total |

|---|

| Basic | Expanded |

|---|

| While taking peripheral venous access through IV cannula | 3 | 3 | 2 | Due to reporting after 72 hours* | 8 |

| While taking sutures | 5 | 3 | 0 | - | 8 |

| Taking blood sample | 4 | 3 | 0 | - | 7 |

| Exposure to non-intact skin by splash of potentially infectious fluid# | 5 | 1 | 1 | PEP indicated but HCW gave negative consent | 7 |

| Exposure to eye or mucus membrane by splash of potentially infectious fluid | 4 | 2 | 0 | - | 6 |

| Exposure to intact skin | 0 | 0 | 4 | PEP not indicated** | 4 |

| While measuring blood sugar from capillary blood by glucometer | 0 | 3 | 0 | - | 3 |

| Handling sharp waste | 1 | 1 | 0 | - | 2 |

| Exposure to least infectious material*** | 0 | 0 | 2 | PEP not indicated*** | 2 |

| Subcutaneous administration of drug | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | 1 |

| Total | 22 | 17 | 9 | - | 48 |

(HCW- Health Care Worker, PEP-Post Exposure Prophylaxis)

* - As per HICC protocol, PEP was not recommended more than 72 hours after exposure; hence it was not given in these two exposures.

# - Potentially infectious fluid include blood, pleural fluid, peritoneal fluid, CSF, pericardial fluid, amniotic fluid, semen and vaginal secretions.

** - Exposure to intact skin has negligible risk of transmission against potential risk of toxicity of PEP drugs; hence as per HICC protocol it was not given. Nonetheless, benefits and risks were explained to HCWs.

*** - Least infectious material include saliva, sputum, tears, vomitus, urine, feces (unless contains visible blood). As per HICC protocol PEP was not recommended in view of insignificant risk of transmission against potential toxicity of PEP drugs. Nonetheless, benefits and risks were explained to HCWs.

Of 39 in whom PEP for HIV was warranted, PEP for HIV was started within two hours in 14 (35.9%) exposures, between two hours to 24 hours in 13 (33.3%) exposures and between 24 to 72 hours in five (12.9%) exposures. In seven (17.9%) exposures, details were not available.

Of 39 exposures in whom PEP for HIV was warranted, 22 received basic regimen with two anti-retroviral drugs and 17 received expanded regimen with three anti-retroviral drugs. Type of regimen used in different circumstances is described in [Table/Fig-3] and detail of drugs used in different regimens is described in [Table/Fig-4]. Indinavir as third drug in expanded regimen was replaced by Lopinavir/Ritonavir after year 2009.

Details of drugs used in different regimens of PEP for HIV.

| Details of regimen | Numbers | Total |

|---|

| Basic | Zidovudine+Lamivudine | 21 | 22 |

| Tenofovir+Emtricitabine | 1 |

| Expanded | Zidovudine+Lamivudine+Indinavir | 9 | 17 |

| Stavudine+Lamivudine+Indinavir | 1 |

| Tenofovir+Emtricitabine+Lopinavir+Ritonavir | 3 |

| Zidovudine+Lamivudine+ Lopinavir+Ritonavir | 4 |

| Total | | 39 |

(PEP-Post Exposure Prophylaxis)

Of 39 HCWs in whom PEP drugs were prescribed, one HCW was lost to follow-up. In remaining 38 who took PEP, most common side effects observed were nausea in 11 (28.9%) incidences followed by fatigue in six (15.8%). Fatigue and nausea both together were observed in five incidences. One HCW had developed rashes (on Zidovudine +Lamivudine) and one had indirect hyperbilirubinemia (on Zidovudine+Lamivudine+Indinavir). One HCW had abdominal pain with vomiting (on Zidovudine+Lamivudine+ Lopinavir/Ritonavir). Considering it possibly Zidovudine intolerance, regimen was changed to Tenofovir+Emtricitabine+Lopinavir/Ritonavir by designated physician, as mentioned in HICC record. One HCW discontinued the drugs after one week due to nausea; remaining all completed therapy of 28 days. All side effects were reported by HCWs on Zidovudine based regimens. Interestingly, all side effects were reported by female HCWs only. Assessment of sero-conversion status after exposure to HIV was done by result of HIV testing at the end of six months. Detail is being described in [Table/Fig-5].

Sero-conversion status of all exposed HCWs to HIV positive source.

| Numbers of HCWs exposed to HIV positive source | Details of PEP given/not given and completion status | Numbers in each subdivision | Sero-conversion status at the end of 6 months | Total |

|---|

| PEP given in 39 exposures | PEP was completed for 28 days | 37 | No sero-conversion | 31 |

| Lost to follow-up | 6 |

| PEP was not completed | 1 | No sero-conversion | 1 |

| Lost to follow up | 1 | Lost to follow-up | 1 |

| PEP not given in 9 exposures | PEP not indicated due to reporting >72 hours* | 2 | No sero-conversion | 2 |

| PEP not given due to exposure to least infectious material** | 2 | No sero-conversion | 2 |

| PEP not given due to exposure to intact skin | 4 | No sero-conversion | 4 |

| PEP not given due to negative consent given by HCW | 1 | Lost to follow-up | 1 |

| Total 48 exposures | - | 48 | No seroconversion | 40 |

| Lost to follow-up | 8 |

(PEP-Post Exposure Prophylaxis)s)

(HCW- Health Care Worker, PEP-Post Exposure Prophylaxis)

*-As per HICC protocol, PEP was not recommended more than 72 hours after exposure; hence it was not given in these two exposures.

** - Least infectious material include saliva, sputum, tears, vomitus, urine, feces (unless contains visible blood). As per HICC protocol PEP was not recommended in view of insignificant risk of transmission against potential toxicity of PEP drugs.

In our study among 48 persons exposed to Hepatitis B, vaccination against Hepatitis B was completed in 33 (68.6%), incomplete but either second or third dose due in eight (16.7%) incidences, incomplete and not on schedule (includes those who have taken either one or two doses of vaccine but have missed remaining dose/doses) in four (8.3%) incidences and not vaccinated in three (6.3%) incidences. Baseline testing for Hepatitis B by HBsAg was done in all exposures and it was negative. [Table/Fig-6] describes anti-HBS antibody titre status of all 45 exposed HCWs with either complete or incomplete vaccination status; the remaining three patients were not vaccinated. Three (12.0%) of 25 who were completely vaccinated were having low titre (< 10 mIU/ml) of anti-HBS antibody. Five of Six who had not completed their vaccine, showed titre >100 mIU/ml but details about number of doses taken was not there, [Table/Fig-7] describes PEP management done for all 48 exposed to Hepatitis B. Of the 17 incidences where titre was not done or low, six received Hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIg). At the end of six months, no sero-conversion was reported in 45 cases and status was not known in three incidences.

Anti-HBS antibody titre status of all exposed HCWs to Hepatitis B.

| Good(>100 mIU/ml) | Marginal(10-100 mIU/ml) | Low(<10 mIU/ml) | Titre result not available |

|---|

| Completed | 17 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Incomplete on schedule | 3 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| Incomplete not on schedule | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 22 (48.9%) | 6 (13.3%) | 3 (6.7%) | 14 (31.1%) |

(HCW-Health Care worker, Anti-HBS – Anti-Hepatitis B Surface antigen)

Detail of PEP management of HCWs exposed to Hepatitis B.

| Vaccination status | Anti-HBS antibody titre | Total numbers in given category | No action | Hepatitis B vaccine | (HBIg) + Hepatitis B vaccine |

|---|

| Completed | Good* | 17 | 17 | - | - |

| Completed | Marginal** | 5 | - | 5 | - |

| Completed | Low# | 3 | - | - | 3 |

| Completed | Not done | 8 | - | 8 | - |

| Incomplete vaccinated on schedule$ | Good* | 3 | - | 3 | - |

| Incomplete vaccinated on schedule$ | Marginal** | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Incomplete vaccinated on schedule$ | Not done | 4 | - | 2 | 2 |

| Incomplete vaccinated not on schedule$$ | Good* | 2 | - | 2 | - |

| Incomplete vaccinated not on schedule$$ | Not done | 2 | - | 1 | 1 |

| Not vaccinated | - | 3 | - | 1 | 2 |

| - | | 48 | 17 (35.4%) | 23 (47.9%) | 8 (16.7%) |

(HCW- Health Care Worker, PEP-Post Exposure Prophylaxis, HBIg-Hepatitis B Immuno-Globulin)

(* Good titre – Anti-HBS antibody titre is >100 mIU/ml, ** Marginal titre – Anti-HBS antibody titre is 10-100 mIU/ml

# Low titre - Anti-HBS antibody titre is <10 mIU/ml)

$ - Incomplete vaccinated and on schedule includes those who have not completed their vaccine and their 2nd and/or 3rd dose/doses of vaccine is/are due.

$$ - Incomplete and not on schedule includes those who have taken either one or two doses of vaccine but have missed remaining dose/doses.

Discussion

Few interesting observations were made in our study; detail of which is described below. In more than half of the exposures to HIV, basic (two drugs) regimen was used regimen expanded (three drugs). Zidovudine based regimens were used in majority but at the same time they were less well tolerated compared to Tenofovir based regimens. All the side effects were observed by female health care workers. Hepatitis B vaccination status was not adequate among HCWs exposed to Hepatitis B positive source. On one side vaccine non-responders were observed and on the other side, good antibody titre was observed in few HCWs even with incomplete vaccination status. No cases of sero-conversion were reported for either HIV or Hepatitis B.

Total 96 incidences of exposure to either HIV and/or Hepatitis B positive source were reported during the period of 13 years. Exposures were one and half times more common in female HCWs compared to males. Study from Romania had 90% exposures in females [31] and a study from Gujarat, India reported male to female ratio of 1:1.8 [28]. Difference in these ratios depends upon overall gender distribution among total HCWs at risk and their involvement in potentially risky procedures. Occurrence of 67.7% exposures reported in later half of study period against 32.3% in first half was significant [Table/Fig-1], this more than two times rise in later half may be due to various factors like increase in bed occupancy, increase in HCWs on job, increased number of procedures involving potential risk or increasing awareness among HCWs leading to increased tendency to report the incidence of accidental exposure.

PEP for HIV: PEP for HIV was started within two hours in only one third of exposures in whom it was warranted. Although this proportion was similar to mentioned in other studies from India and elsewhere [11,14,21,22,25,26,28]; various guidelines clearly recommends to start PEP preferably within two hours to have its best efficacy [2,3,30]. Not able to start within two hours, emphasizes the need for HICC and hospital administrators to analyze reasons for this delay and to focus its efforts to start PEP at the earliest. Choice between basic or expanded regimens was based on severity of exposure as per recommendations in earlier guidelines of NACO, India [2] and CDC [3,30]; more recent guidelines by CDC [32] and WHO [4] recommend expanded regimen (three drugs) irrespective of severity of exposure. While study by Mehta A et al., and S. Malhotra et al., have described use of two or three drugs regimens depending upon severity of exposure [27,33], study by Cai Juan and by Amrita Shriyan et al., have mentioned use of three drugs in all exposures as a part of hospital protocol [24,26]. In our study also basic regimen was used in more than half of the indicated cases of exposure. NACO, India guidelines, updated in 2009, also recommends choice of PEP regimen based on severity of exposure [29]. Other than this, we could not find further updated guidelines given by NACO, India.

In relation to choice of drugs used as PEP for HIV, Zidovudine based regimen was used in majority of incidences in our study. While older guidelines had recommendation of Zidovudine based regimens as first choice [2,3,30]; recent studies [21,23] and guidelines [4,32] have described Tenofovir based regimen as first choice due to its better tolerability and favourable side effects profile. Various studies from India and other countries have described use of Zidovudine based regimens in majority or all of their study population [22,24,26,27]. Lack of awareness as well as lack of availability of Tenofovir were probably the reasons for not using Tenofovir based regimens especially in resource limited countries. A study from China also described the non-availability of Tenofovir based regimen as the reason for not including it as first choice drug for PEP [24].

In our study before year 2009, Indinavir was used as third drug for PEP; which was replaced by Lopinavir/Ritonavir since 2009 based on updation in guidelines by CDC in year 2005 [30] and NACO in year 2009 [29]. Choice of third drug in PEP regimen has changed over the period of time in guidelines given by national and international bodies. As mentioned in earlier (2001) guidelines by CDC [3] and in other studies [34,35], Indinavir was used as first choice. With recognition of more side effects with Indinavir; later on Lopinavir/Ritonavir was recommended as first choice by CDC in 2005 [30] and by NACO, India in 2007 [2]. Year 2013 guidelines by CDC now recommend Raltegravir as first choice in view of its better tolerability, less drug-drug interactions and convenience of administration [32]. But due to uncertain availability and high cost of Raltegravir, Lopinavir/Ritonavir is still being recommended as first choice by NACO, India guidelines of 2009 [29] and by WHO guidelines of 2014 [4]. While study by Amrita Shriyan from Karnataka, India [26] has mentioned use of Indinavir as third PEP drug, majority of the studies have described use of Lopinavir/Ritonavir as third PEP drug [21,23,24].

Another interesting finding of our study was better tolerance and overall favorable side effect profile of PEP for HIV, compared to studies reported from other countries. Nearly only one third HCWs reported side effects in our study compared to very high percentage observed in other studies. Himmelreich H et al., from Frankfurt observed poor tolerability of PEP in 58.5% and moderate tolerability in 31.7% and better tolerability in only 9.8% of study population [21]. Raymond A Tetteh et al., from Ghana observed side effects in 91% of study population who received Zidovudine+ Lamivudine and in 96% of study population who received Zidovudine+ Lamivudine+ Lopinavir/Ritonavir combination [22]. Juan Cai et al., from China also observed fatigue in 88.5%, nausea, vomiting in 57.6%, liver dysfunction in 38.5% and drug rash in 69.2% [24]. One of the reasons for this difference may be because of our study being retrospective record based study rather than verbal interview based, of exposed HCWs. Whether genetic difference between different populations was also contributing in this variation or not, is not known. Fatigue and nausea were most common side effects reported in most of the studies. In our study, all side effects were reported by HCWs who were on Zidovudine based regimens. Tenofovir based regimen was well tolerated, although only four of 39 received Tenofovir based regimen. Better tolerability of Tenofovir based regimen was also observed in other studies [13,22,23,25] and with similar observations; majority recent guidelines also recommend Tenofovir based regimen as first choice as mentioned above [4,32]. Yet, guideline by NACO, India [29] still recommends Zidovudine based regimen as first choice of PEP therapy. In our study, all side effects were reported by female HCWs only. Heiko Himmelreich also reported less tolerance in female gender [21], while Raymond A. Tetteh et al., in their study done at Ghana, reported no gender difference in terms of tolerability of PEP drugs for HIV [22]. PEP was completed by most of the HCWs in our study; Heiko Himmelreich et al., reported only 59% completion rate due to poor tolerance [21]. Study from Gujarat, India reported 94% completion rate [28] and from China also reported 93% [24]. No sero-conversion was reported from available data, six exposed HCWs did not turn up for testing. Similar observations were made in other studies [21,26–28,36]. CDC reported 58 confirmed and 150 possible cases of occupationally transmitted HIV during period of 1985-2013 [37].

PEP for Hepatitis B: Inadequacy of Hepatitis B vaccination status among HCWs exposed to Hepatitis B as observed in our study, was similar to observations made in other studies [6,16,20,26,35,38,39]. Nevertheless, HICC should target 100% vaccination of all HCWs as well as medical, paramedical and nursing students in teaching institutes; considering high transmission rate of Hepatitis B in occupational setting and availability of otherwise this easy and effective tool to minimize the Hepatitis B transmission. We found 12.0% of vaccine non-responders among HCWs completely vaccinated against Hepatitis B, similar to described in other studies [21,27,31,40]. CDC has emphasized need for compulsory anti-HBS antibody screening of all vaccinated HCWs [40]; lack of awareness as well as lack of availability of diagnostic facility are some of the important reasons for titre not being done compulsorily especially in resource limited countries. On the other side, five of six incompletely vaccinated HCWs were also having titre of >100 mIU/ml. This demonstrates good efficacy of vaccine even with incomplete schedule and again emphasizes need to focus on 100% vaccination rate. Of 17 incidences where titre was not done or low, only six could receive Hepatitis B immunoglobulin. NACO, India recommends only Hepatitis B vaccine in such situations [2,29] probably because of limited availability as well as very high cost of HBIg; CDC [3,40] recommends HBIg for all exposures by unvaccinated HCWs or those having low titer. Inspite of high transmission rate, no case of sero-conversion was reported in our study from available data suggesting relatively good efficacy of vaccine as well as PEP.

Limitation

There were certain limitations also of our study. This study was done from reported incidences to HICC; unreported exposures were not included. No details were available on HIV viral load and CD4 count of source patients. No details were available on baseline as well as follow-up blood investigations (other than HIV) of HCWs exposed to HIV positive sources; subclinical hematological or hepatic abnormalities, might have been missed while studying side effects of PEP for HIV. HICC record had no mention of details of first aid taken after the exposure; appropriate and timely first aid also plays an important role in reducing chances of occupational transmission. Nevertheless, our study has a mention on remaining details of PEP; which is been described in only limited studies from India to the best of our knowledge. It has made an attempt to represent actual scenario from resource limited health care centers especially of developing countries. We believe, information derived will be useful atleast to some extent while forming policies related to infection control and PEP management by HICC and hospital administrators.

Conclusion

Choice of basic or expanded regimens was made according to severity of exposure rather than expanded regimen in all exposed to HIV. Zidovudine based regimens were used in majority but were less well tolerated compared to Tenofovir based regimens. Overall PEP for HIV was well tolerated with fewer side effects contrary to higher rate of intolerance observed in studies reported from countries other than India. All side effects were reported by female HCWs. Hepatitis B vaccination status was not adequate among HCWs exposed to Hepatitis B. Like documented in other studies, we also observed one tenth proportion of vaccine non-responders. This emphasizes the need for compulsory screening of anti-HBs antibody titer for all HCWs at the time of joining the job to identify this population. On the other side, good antibody titer was observed in few HCWs with incomplete vaccination status, suggesting vaccines to be used as easy and effective tool for HCWs. Although CDC recommends HBIg administration if exposure occurs to non-vaccinated HCWs or vaccine non-responders; same may not be possible to give in resource limited countries like India due to lack of availability and high cost as was observed in our study. No cases of sero-conversion were reported. Along with PEP, round the clock availability of system to manage occupational exposures also probably played an important role in preventing occupational transmission as observed in our study.

HCW- Health Care Worker

(HCW- Health Care Worker, PEP-Post Exposure Prophylaxis)

* - As per HICC protocol, PEP was not recommended more than 72 hours after exposure; hence it was not given in these two exposures.

# - Potentially infectious fluid include blood, pleural fluid, peritoneal fluid, CSF, pericardial fluid, amniotic fluid, semen and vaginal secretions.

** - Exposure to intact skin has negligible risk of transmission against potential risk of toxicity of PEP drugs; hence as per HICC protocol it was not given. Nonetheless, benefits and risks were explained to HCWs.

*** - Least infectious material include saliva, sputum, tears, vomitus, urine, feces (unless contains visible blood). As per HICC protocol PEP was not recommended in view of insignificant risk of transmission against potential toxicity of PEP drugs. Nonetheless, benefits and risks were explained to HCWs.

(PEP-Post Exposure Prophylaxis)

(PEP-Post Exposure Prophylaxis)s)

(HCW- Health Care Worker, PEP-Post Exposure Prophylaxis)

*-As per HICC protocol, PEP was not recommended more than 72 hours after exposure; hence it was not given in these two exposures.

** - Least infectious material include saliva, sputum, tears, vomitus, urine, feces (unless contains visible blood). As per HICC protocol PEP was not recommended in view of insignificant risk of transmission against potential toxicity of PEP drugs.

(HCW-Health Care worker, Anti-HBS – Anti-Hepatitis B Surface antigen)

(HCW- Health Care Worker, PEP-Post Exposure Prophylaxis, HBIg-Hepatitis B Immuno-Globulin)

(* Good titre – Anti-HBS antibody titre is >100 mIU/ml, ** Marginal titre – Anti-HBS antibody titre is 10-100 mIU/ml

# Low titre - Anti-HBS antibody titre is <10 mIU/ml)

$ - Incomplete vaccinated and on schedule includes those who have not completed their vaccine and their 2nd and/or 3rd dose/doses of vaccine is/are due.

$$ - Incomplete and not on schedule includes those who have taken either one or two doses of vaccine but have missed remaining dose/doses.