Several studies have observed the validity of self-reported periodontal disease and possible items for detection [1]. Periodontitis is still highly prevalent in industrial population whereas at the same time appropriate screening programs are missing. Authors in different studies have described different numbers of suitable periodontitis screening questions and conventional risk indicators such as age, gender, smoking behaviour, tooth-mobility, recession, gum bleeding and accomplished periodontal therapy [1–5]. Whereas further important risk indicators like nutrition, body-mass-index, dental prosthetics, alcohol consumption, stress and the educational level have not been mentioned appropriately [6–14]. Hence, to incorporate this aspect a new questionnaire that pays adequate attention to all present known periodontal risk indicators/factors must be evolved. These new elaborated items will enable users to indicate periodontitis incidence more precisely.

First of all, it must be stated that patients hosting periodontal pathogens do not implicitly develop periodontal disease. The disease progression also requires a susceptible host [15,16]. The determining factors for the onset of periodontal disease and their progression have been detected based on the results of current studies, systematic reviews and consensus conferences focusing on the individual results in the preceding years [17–20]. It became apparent that there are, in some cases, extremely differing results and that an evaluation cannot proceed based on a standardised principle [21]. The complex interaction of periodontal risk factors, systemic disease and innate factors currently permits a definite prognosis of the incidence and progression of periodontitis [22].

The applicable approach within modern periodontitis therapy should provide early care for high-risk patients, susceptible to an increased incidence of periodontitis. The current situation is characterized by an inadequate care provided to diseased persons in Germany, whereby conservative estimates in the oral health study from 2006 showed that approximately eight million people suffer from an advanced form of periodontitis (PSI equal to 4), while merely 980,900 treatments are billed [23, 24]. The majority of the patients are not aware of their situation and later present with advanced periodontitis at the dental clinic.

A screening test comprising of questionnaire used by different clinicians (e.g., family doctors, cardiologists), insurance companies (e.g., check-up, incentives through loyalty programs) or as a web-based application could increase awareness and acceptance of prevention measures.

The aim of the study was to evaluate a new questionnaire, based only on patients-reported data for periodontitis screening. In order to review the robustness of the screening test with respect to the prevalent severity of periodontitis, different periodontitis classifications (Perio 1, 2, 3) were defined.

Materials and Methods

The present clinical trial was approved by the Ethics Commission at the Medical Faculty in Leipzig (337-13-18112013). Before commencing the double-blind, controlled clinical trial (ID NCT02754401), all study participants were informed of its content and the use of personal data and confirmed their voluntary willingness to take part, in writing.

Patients: A newly developed questionnaire was used as part of a preliminary dental examination to interview a total of 200 patients concerning the clinical indications and periodontal risk factors of periodontitis. The clinical follow-up examination was conducted by the Periodontal Screening Index (PSI) [25]. To include representative periodontitis patients, a consecutive sampling was applied. Every patient meeting the criteria of inclusion was selected till the required sample size was achieved. The sampling was finished until each group reached a number of hundred patients. To reduce the so-called center effect the patients were exclusively new and untreated [26]. Thereby, they were all unknown for the examiners. Additionally investigators and patients did not know the purpose of the questionnaire before taking it. Patients were also required to be at least 18 years to take part in the study. Patients undergoing periodontal treatment, antibiotic therapy, pregnant and disabled persons were excluded from the study. Finally for statistical analysis participants were divided into two groups of non-periodontitis patients (Group 1; PSI Code 0, 1, 2) and periodontitis patients (Group 2; PSI Code 3 and 4) for the first PSI classification (Perio 1).

Periodontal Situation (PSI, PSR®)

The Periodontal Screening Index (PSI in Germany) or Periodontal Screening and Recording (PSR®) [12,13] was registered based on a WHO probe (Morita, Kyoto, Japan). The set of teeth was divided into sextants for the purpose of the investigation. The PSI Codes (0 to 4) were recorded: Code 0=healthy, Code 1=bleeding, Code 2=supra-/subgingival calculus, Code 3=probing depths from 3.5mm to maximum 5.5mm, Code 4=probing depths greater than 5.5mm. Only the highest finding was noted for each sextant. Subjects with findings of Code 0 to Code 2 were classified as non-periodontitis subjects (Group 1), whereby Codes 3 and 4 were considered probable periodontitis subjects (Group 2). Two additional PSI classifications were defined in order to review the robustness of the screening test with respect to the prevalent severity of periodontitis. Classification Perio 2 comprised subjects with a PSI Code 0, 1, 2 and once Code 3, indicating non-periodontitis, while subjects recording Codes 3 or 4 on one occasion were periodontitis subjects. In the third classification (Perio 3), only such patients who exhibited at least one Code 4 were considered as periodontitis subjects, while all others were evaluated as non-periodontitis subjects.

All clinical recordings were performed by the same calibrated examiners. Examiner calibration was performed as follows: five adults, not enrolled in the study, were evaluated by the examiners on two separate occasions, 48 hours apart. Calibration was accepted if the millimetre measurements at baseline and 48 hours later did not differ more than 10 percent.

Questionnaire: The questionnaire was initially prepared by a retrospective selection of suitable items reviewed in current literature on the subject of periodontal risk factors and indicators. Research was conducted using PubMed, whereby only articles written in English were included. Systematic reviews and randomised, controlled studies were preferred. Based on this 16 questions [Table/Fig-1] were developed. The individual response options were assigned point values extending from zero to eight, based on their assumed degree of influence on the periodontal disease. To determine the correct wording and phrasing, the questionnaire was given as a pre-test to 20 patients not included in the study.

| Question | Score |

|---|

| 1. Are you male or female? |

| Female | 0 |

| Male | 2 |

| 2. How old are you? |

| Under 35 | 0 |

| 35-65 | 5 |

| Over 65 | 8 |

| 3. The following is needed to calculate your BMI ___weight (in kilograms) ___height (in metres) |

| Under 25 | 0 |

| 25-30 | 1 |

| Over 30 | 2 |

| 4. How would you describe your dietary habits? |

| I tend to eat irregularly and with little variety. | 2 |

| I would describe my diet is normal. | 1 |

| I maintain a balanced diet and am concerned that my food is prepared fresh. | 0 |

| 5. Which was the final grade at school you attended? |

| Below 10th grade | 3 |

| 10th grade | 1 |

| 12th, i.e., 13th grade | 0 |

| 6. Do you suffer for one or more of the diseases listed hereafter (multiple answers possible)? |

| Diabetes | 3 |

| Osteoporosis | 2 |

| Heart disease | 1 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 |

| Depression | 2 |

| None known | 0 |

| 7. Does anyone in your family (parents or siblings) suffer from gum disease? |

| Yes | 1 |

| No | 0 |

| 8. To what extent do you believe that you suffer from chronic stress (work-related, family, social stress or worry)? |

| Not much | 0 |

| Moderately | 1 |

| Severely | 2 |

| 9. Please provide information on your smoking behaviour. |

| I have never smoked. | 0 |

| I am a former smoker or occasional smoker. | 1 |

| I used to be a heavy smoker. | 3 |

| I smoke up to 10 cigarettes per day. | 2 |

| I smoke more than 10 cigarettes per day. | 3 |

| 10. Please provide information on your alcohol intake. |

| I never drink alcohol, or drink alcohol infrequently. | 0 |

| I drink alcohol more frequently (2-3 times per week). | 1 |

| I frequently drink alcohol (at least 4 times a week). | 2 |

| 11. How often do you visit a dentist? |

| I try to avoid visiting a dentist. | 2 |

| I go for an annual dental check-up. | 1 |

| I visit the dentist regularly and also receive professional tooth cleaning. | 0 |

| 12. Have your gums already been treated? |

| I have received no treatment. | 1 |

| My last gum treatment was over 10 years ago. | 3 |

| A treatment has already been conducted, but there was no regular follow-up. | 2 |

| A treatment was conducted, and since then there have been regular follow-ups. | 0 |

| 13. Have you observed an increase in the incidence of bleeding gums? |

| Yes | 2 |

| No | 0 |

| 14. Have you noticed any increase in exposed root surfaces? |

| Yes | 2 |

| No | 0 |

| 15. Please provide assessment on the movability of your teeth. |

| I have never noticed any increase in tooth movability. | 0 |

| The position of my teeth has changed. | 1 |

| Some teeth are loose. | 2 |

| I have already lost teeth due to increased loosening or gum problems. | 3 |

| 16. Please provide information on your dental prosthetics. |

| I do not have any dental prosthetics. | 0 |

| I have several crowns, bridges or implants. | 1 |

| I have removable dentures. | 3 |

Statistical Analysis

Statistical evaluation was conducted using SPSS for Windows, Version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., NY, U.S.A.) and BiAS for Windows, Version 10.12. (epsilon-Verlag GbR, Hochheim Darmstadt, Germany). The sample size (200 participants) was calculated with an expected standard deviation of four score points, minimal different score point delta between 1.6 and 2, p-value of 0.05 and a power of 0.8 [27]. The categorised data was evaluated based on the Chi-squared test (question 2-6, 8-12, 15, 16), the precise test according to Fisher (question 1, 7, 13, 14). A two-sided review of significance was applied to each of the tests, whereby a p-value of <0.05 was assumed to be statistically significant for all statistical tests.

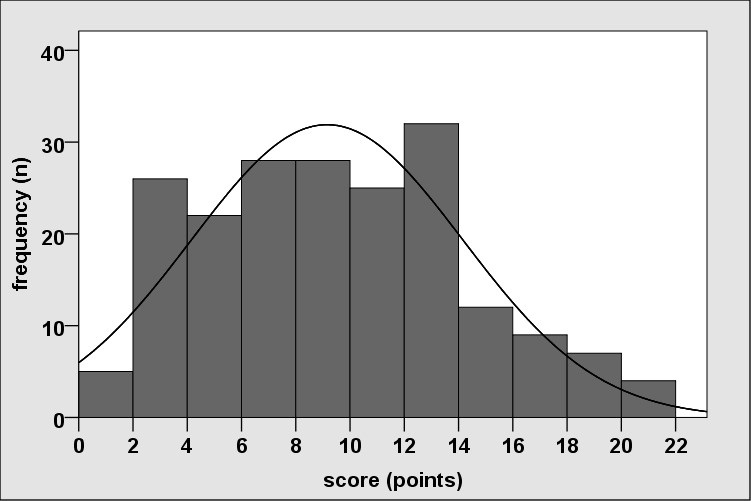

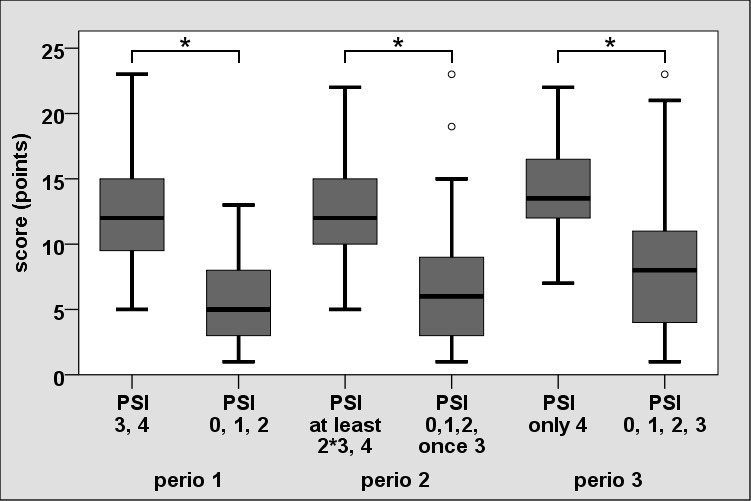

The distribution of total score was reviewed according to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test in terms of normal distribution. The score did not exhibit a normal distribution (Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test: p<0.05). Furthermore the Mann-Whitney U-test was applied in the comparison of scores based on the variety of periodontitis classifications (differentiated consideration of periodontally diseased persons) and box plots were created to elucidate the data.

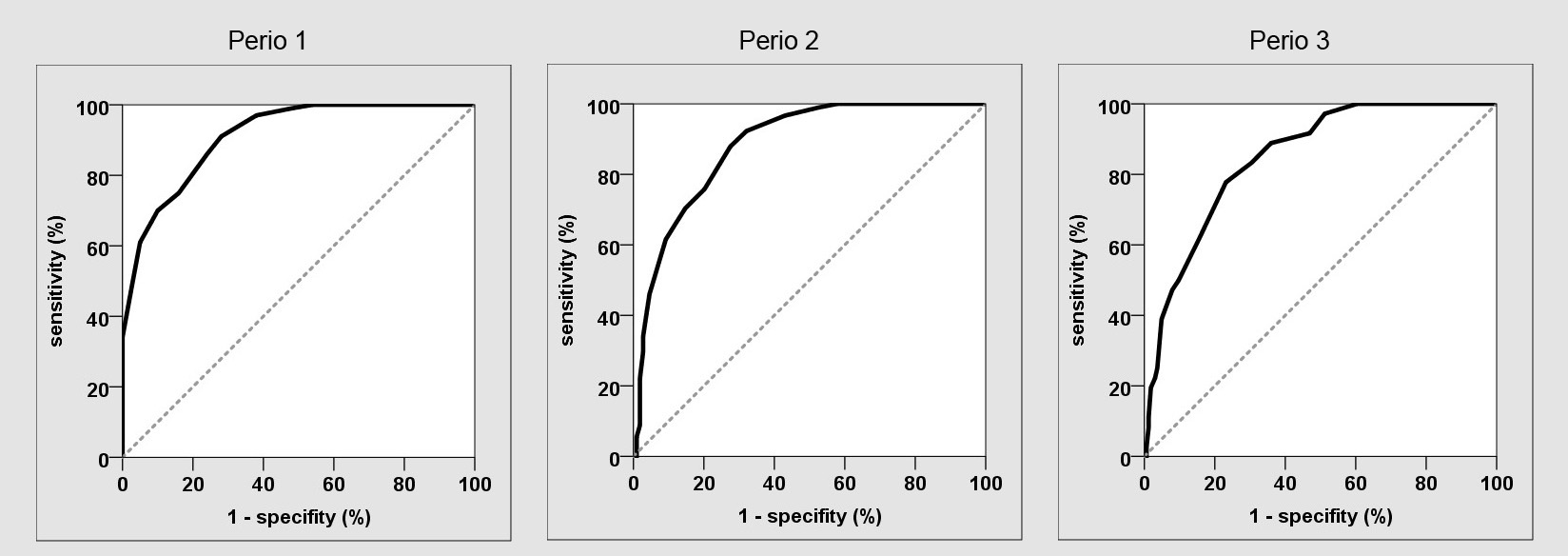

ROC curves were produced to illustrate sensitivity and specificity. The area under the ROC curve (AUC), which in a test without forecast reliability will be 0.5 and not more than 1, is a benchmark to measure forecast reliability. The cut-off point was defined as beyond a sensitivity of at least 80% with the greatest possible specificity in order to meet the requirements of a screening test.

Results

A total of 200 patients took part in the clinical trial, respectively comprising 100 healthy patients (Group 1) and 100 patients with periodontitis (Group 2). The study was conducted over a period of six months.

A statistically significant distinction (p<0.05) relating to the patients’ prevalent PSI (Perio 1) was verified for 12 of the 16 items [Table/Fig-2]. Statistical evaluation revealed significant differences between the two groups with regard to the basic parameters in terms of gender (p=0.016), age (p<0.001) and Body Mass Index (BMI, p=0.042). In terms of nutrition, an improvement in the dietary situation revealed a simultaneous increase in the number of persons with good periodontal health. This effect ran contrary to a decrease in the number of persons with a conspicuous periodontal condition (p=0.003). Concerning the educational level, there was a clear correlation verified between the rise in numbers of healthy patients and higher levels of education, concomitant with a decrease in the number of periodontitis patients (p=0.002). A comparison between the two groups with respect to prevalent diseases did not indicate any significant distinction (p=0.135). All three diabetic patients and four of the five patients with multiple diseases registered in the group of periodontally conspicuous patients. The difference in terms of a family history for more frequent gum diseases was statistically significant (p=0.042).

Socio-demographic and relevant characteristics of participants (Perio 1).

| Risk Indicator | Periodontal Screening Index | p-value |

|---|

| PSI 0, 1, 2n (%) | PSI 3, 4n (%) | Totaln (%) |

|---|

| Gender |

| Female | 62 (58.5) | 44 (41.5) | 106 (53) | 0.016 |

| Male | 38 (40.4) | 56 (59.6) | 94 (47) |

| Age (year) |

| <35 | 75 (72.1) | 29 (27.9) | 104 (52) | <0.001 |

| 35-65 | 25 (27.5) | 66 (72.5) | 91 (54.5) |

| >65 | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 5 (2.5) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) |

| <25 | 77 (55.4) | 62 (44.6) | 139 (69.5) | 0.042 |

| 25-30 | 21 (40.4) | 31 (59.6) | 52 (26) |

| >30 | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | 9 (4.5) |

| Nutrition |

| Unbalanced | 8 (26.7) | 22 (73.3) | 30 (15) | 0.003 |

| Normal | 49 (48) | 53 (52) | 102 (51) |

| Balanced | 43 (63.2) | 25 (36.8) | 68 (34) |

| Years of Education |

| <10 | 3 (27.3) | 8 (72.7) | 11 (5.5) | 0.002 |

| 10 | 26 (36.6) | 45 (63.4) | 71 (35.5) |

| ≥12 | 71 (60.2) | 47 (39.8) | 118 (59) |

| Disease |

| Diabetes | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 3 (1.5) | 0.135 |

| Heart disease | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | 7 (3.5) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 (25) | 3 (75) | 4 (2) |

| Depression | 5 (41.7) | 7 (58.3) | 12 (6) |

| Several disease | 1 (20) | 4 (80) | 5 (2.5) |

| Unknown | 91 (53.8) | 78 (46.2) | 169 (84.5) |

| Family/Parental History |

| Yes | 12 (33.3) | 24 (66.7) | 36 (18) | 0.042 |

| No | 88 (53.7) | 76 (46.3) | 164 (82) |

| Stress |

| Low | 27 (48.2) | 29 (51.8) | 56 (28) | 0.944 |

| Medium | 47 (51.1) | 45 (48.9) | 92 (46) |

| High | 26 (50) | 26 (50) | 52 (26) |

| Smoking |

| Non-smoker | 63 (81.8) | 14 (18.2) | 77 (38.5) | <0.001 |

| Occasion/ex-smoker | 25 (41) | 36 (59) | 61 (30.5) |

| Strong ex-smoker | 3 (21.4) | 11 (78.6) | 14 (7) |

| ≤10 cigarettes daily | 5 (25) | 15 (75) | 20 (10) |

| >10 cigarettes daily | 4 (14.3) | 24 (85.7) | 28 (14) |

| Alcohol Consumption |

| Non or occasion | 77 (51.3) | 73 (48.7) | 150 (75) | 0.25 |

| 2-3 times/ week | 22 (50) | 22 (50) | 44 (22) |

| ≥4 times/ week | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | 6 (3) |

| Dental Care |

| None | 22 (43.1) | 29 (56.9) | 51 (25.5) | 0.24 |

| Annual inspection | 57 (60) | 38 (40) | 95 (47.5) |

| Regular monitoring and tooth cleaning | 21 (38.9) | 33 (61.1) | 54 (27) |

| Periodontal Therapy |

| None | 93 (56.7) | 71 (43.3) | 164 (82) | 0.001 |

| >10 years | 0 (0) | 6 (100) | 6 (3) |

| Therapy without supportive measures | 3 (27.3) | 8 (72.7) | 11 (5.5) |

| Therapy with supportive measures | 4 (21.1) | 15 (78.9) | 19 (9.5) |

| Gingival Bleeding |

| Yes | 9 (20.9) | 34 (79.1) | 43 (21.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 91 (58) | 66 (42) | 157 (78.5) |

| Exposed Root Surfaces |

| Yes | 12 (30) | 28 (70) | 40 (20) | 0.007 |

| No | 88 (55) | 72 (45) | 160 (80) |

| Tooth Mobility |

| No | 91 (56.2) | 71 (43.8) | 162 (81) | <0.001 |

| Position alteration | 9 (52.9) | 8 (47.1) | 17 (8.5) |

| Tooth loosening | 0 (0) | 11 (100) | 11 (5.5) |

| Tooth loss on the basis of mobility | 0 (0) | 10 (100) | 10 (5) |

| Dental Prosthetics |

| None | 75 (69.4) | 33 (30.6) | 108 (54) | <0.001 |

| Fixed | 25 (30.1) | 58 (69.9) | 83 (41.5) |

| Removable | 0 (0) | 9 (100) | 9 (4.5) |

No significant distinction (p=0.944) was verified between the two groups based on the prevalence of different levels of stress. Smoking behaviour and its repercussions on periodontal disease exhibited high statistical significance (p<0.001). In terms of their alcohol intake no significant distinction was detected between the two groups (p=0.25), although the frequency of periodontitis patients with high alcohol consumption was five times higher when compared with healthy patients.

A statistically significant difference was verified between the two groups in terms of dental care (p=0.024). However, no constant rise in periodontal health was observed based on more intense dental care. Analysis of the data concerning a prior periodontitis therapy revealed a significant rise in subjects suffering from periodontal disease among those who had already received therapy (p=0.001). Surveying the patients with respect to gum bleeding revealed substantially greater number of periodontitis patients suffering from bleeding (p<0.001). Subjects already diagnosed with exposed root surfaces also exhibited greater numbers of periodontal problems (p=0.007). An analysis of tooth mobility and prior incidence of tooth loss was highly significant with a distinct rise in those suffering from periodontal disease (p<0.001). The question concerning dental prosthetics exhibited high statistical significance (p<0.001) with a clear increase in those suffering from periodontitis, based on the rise in scope and decrease in anchor quality of the prosthesis.

Only 12 of the 16 items (without questions regarding diseases, stress level, alcohol intake and dental care) exhibited a statistically significant distinction based on the PSI value (p<0.05). They were included in the calculation of total score [Table/Fig-3]. The distribution of the total score revealed highly statistical significant difference (Group 1: 5.69 ± 3.25; Group 2: 12.6 ± 3.94; p<0.001). Two additional PSI classifications (Perio 2,3) were defined in order to review the robustness of the screening test. In this, the differentiated consideration of periodontally diseased persons also indicated results with a high statistical significance (p<0.001) [Table/Fig-4].

Distribution of the total score (12 items).

Distribution of the total score based on differentiated consideration of non-periodontitis and periodontitis persons (Perio 1, 2, 3).

The AUC was 0.912 [Table/Fig-5]. Cut-off was applied at eight score points (non-periodontitis≤8 vs. periodontitis>8) with a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 76% (AUC=0.81).

Receiving operating characteristic curve (ROC) for different PSI classifications (Perio 1, 2, 3).

Discussion

The objective of the clinical trial was to conceive a new periodontal risk indicator system based entirely on patient-recorded data. The current variance in study design and study results concerning the influence of endogenous and exogenous risk factors and indicators for periodontitis could not draw clear conclusions [21]. This is why an intentional and relatively rough subdivision of the point values was chosen for the individual response options concerning the putative degree of influence, ranging from zero to three. The only exception was made in the evaluation of age, in which points were awarded ranging from zero (under 35 years) to five (35 to 65 years) up to eight points (aged over 65). It is suspected that the patients’ age acts as a multiplier of existing risk factors [23, 28–30].

Several univariate and multivariate analysis revealed that demographic features (age, gender, smoking history, education level), patient self-reported symptoms (tooth mobility, gum bleeding, root surface) and treatment history were predictive for periodontitis [3,5]. In a systematic review Blicher et al., discussed conflicting results when repeating self-reported questions in different studies [1]. For example, self-reported bleeding of gum was examined by six studies and only three of them published appropriate statistics. Of these three, two found that it was a valid measure for periodontitis and one found it was not [31, 32]. There is no obvious factor explaining the differences between studies in finding self-reported questions to be valid or not. The combined use of several questions might improve the sensitivity and specificity of the approach [4].

In the present study 12 of the 16 items exhibited a statistically significant distinction based on the PSI value (p<0.05). Advanced age, male gender, BMI, balanced nutrition, smoking behaviour, family history, level of education, gum bleeding, exposed root surface, tooth loss and prior periodontal treatment were significant markers for periodontitis.

One of the most controversial indicators, refers to the socio-economic status. Besides income, relationship status and attendant risks such as smoking and obesity as well as additional socio-economic status factors, the prevalence of differing levels of education was found to have an influence on periodontal disease [33, 34]. Herein, persons (2595 test participants) with lower school qualifications were exposed to a greater risk of periodontal disease [35].

Besides insufficient periodontal care, prosthetic systems worn by patients appear to have a substantial influence on the incidence of periodontitis [9,10]. Compared with fixed systems, patients with removable dentures exhibit substantially greater periodontal problems [36]. This observation was also confirmed by the current study, as shown in the highly significant accumulation of persons suffering from periodontal disease within the group of patients wearing prosthetic systems (p<0.001).

The positive effect of dental care on periodontal disease incidence, already assumed in prior studies, was confirmed (p=0.024) [37]. However, this study did not show any improvement based on greater intensity of care involving professional tooth cleaning. Quite the contrary, the accumulation of persons with periodontal diseases was the highest, registering at almost 61%, in this group. This is probably caused by insufficient periodontal therapy where professional tooth cleaning is applied as a sole means of therapy for initial, clinically visible inflammatory symptoms of a periodontal disease that has actually progressed further.

The questionnaire had a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 76%. Hence, the probability that any person recording a positive test result would nevertheless be healthy was around 11% [38]. The best possible distribution was selected based on the Area Under the Curve (AUC=0.81) considering that the PSI constitutes a relatively rough assessment of the disease and that the excessively high specificity places obstacles in identifying so-called risk patients. Before comparing studies concerning sensitivity, AUC and validity, it has to be mentioned that there is no generally accepted definition of periodontal disease and examination [39]. By way of illustration examiners used panoramic radiographs [5], measured probing depth and clinical attachment loss on only two sites per tooth in two randomly selected quadrants or on three or six sites of all teeth [2–4]. A different composition of the investigated population for developing predictive models may limit a common use. Prevalence of the disease in the population group designated for testing is of crucial importance with respect to the ratio of sensitivity and specificity [40]. Roughly 50 to 70 percent of adults suffered from periodontitis [29,40,41] hence, the main focus must be on identifying persons exhibiting periodontal disease and so called high-risk patients. Referring to that, Wu et al., [42] validated two different predictive models developed by Yamamoto et al., and Dietrich et al., [3,5]. Yamamoto’s model derived from only males in a police department without severe dental problems, whereas Dietrich’s model derived from a group of patients that obtained endodontic surgery. Because of that the AUC values fluctuate from 0.67 to 0.89 for moderate periodontitis and from 0.78 to 0.93 for advanced periodontitis. Consequently, the validation of different predictive models was distinct when testing capability on equal population. To avoid such discrepancy in the present study a consecutive sampling was applied to receive a representative population. For Yamamoto’s questionnaire, derived from 250 male persons, only four items reached a sensitivity of 0.73 and specificity of 0.8. The AUC was also 0.81. Another study with a questionnaire of 18 items (yes or no) and an additional survey of socio-demographic characteristics of patients calculated an AUC from 0.77 up to 0.83 according to different clinical periodontitis definitions [4]. The sensitivity ranged between 0.61 and 0.83 and the specificity from 0.69 up to 0.83. Only six questions were significantly associated with periodontal disease. Slade et al., observed the validity of periodontitis screening questions and common known risk indicators in nearly 3000 persons [2]. The combination of eleven questions was useful for prediction of moderate and advanced periodontitis. According to three different regression models, the sensitivity and specificity ranged varying strong from 0.23 up to 0.97. These results are similar to the current study and indicate that there is a limit in reliability of data for determining periodontitis incidence independently from different periodontitis definitions or the number of items.

Limitation

There exists clear limitations in detecting periodontitis incidence regarding sensitivity and specificity. It is suggested to use the current questionnaire as means of precaution for patients, different clinicians and also for companies in the dental market. The findings of this study should be confirmed by further investigations regarding validation with other known predictive models and larger size of participants.

Conclusion

In summary, this clinical trial indicates that a reliable detection of representative periodontitis patients using patient-reported data on periodontal risk factors and indicators is possible.

The newly developed questionnaire produced a reliable assessment of the individual risk (total score) and the need for periodontal treatment as well as the differentiation between gingivits and peridontitis.