Diverticular diseases are more common in colon with a prevalence rate of 5 to 45% in western and industrial nations [1]. Next to it, duodenum is the most common site for diverticulum. Various modalities like barium meal, upper GI endoscopy, ultrasonography, Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance and Imaging (MRI), ERCP, Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) [2,3] can be used for diagnosing Duodenal Diverticulum (DD). The prevalence rate of DD varies from 1 to 22% depending upon the mode of investigation [4]. Its incidence ranged from 1–6% based on X- rays, 2-22% in autopsy [4] and 5.6% by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) [5]. However, the actual incidence of DD is not known because most of them are asymptomatic [6].

Of the various modalities of diagnosing DD, CT enables accurate assessment of both the intraluminal and extraluminal components of the diverticular disease and the involvement of other nearby organs and distant disease [7]. CT scan has a documented diagnostic accuracy rate of 90% to 95% in diagnosing diverticular diseases [8] and is considered to be the test of choice due to its high sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and availability as compared to other modalities of investigation [9]. Though the complications of DD are rare, haemorrhage and perforation are the dreaded complications with high mortality rate [10]. The present study aim to look for the prevalence of DD in Indian population using Contrast Enhanced Computed Tomography (CECT) abdomen.

Materials and Methods

This was an Institutional Review Board and Ethics committee approved retrospective study conducted in a tertiary care teaching hospital in South India. All the CECT abdomen including all age groups, performed over a period of one month (September 2013) in the Department of Radiology for varying clinical conditions, performed using 6 slice CT scanner (Brilliance CT; Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) with slice thickness of 2mm with reconstruction interval of 0.75mm were included in the study. The total number of cases included in this study was 565 (male - 314; female – 251). The age of the patients included in the study ranged from 8 weeks to 85 years (mean 44.90 ± 15.36).

The automated 2mm axial and coronal reformats were generated and was reviewed from Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) workstation (GE medical system) by a consultant radiologist. CT was assessed for the presence of duodenal diverticulum, number, size, location, relative wall thickness and content of the diverticulum. Abdominal CT examinations during the study period of patients who underwent surgical procedures that might have altered the anatomy of the duodenum or led to the removal of duodenum and of those patients with large mass lesions in the liver, gallbladder, duodenum, stomach and pancreas which would cause distortion of duodenum; and those patients with large peri-pancreatic collections and massive ascites and CT images with movement artefacts were excluded from the study.

Statistical Analysis

Clinical details of the patients were obtained from clinical workstation. Data collected were statistically analysed using SPSS software version 17.0. Descriptive statistics namely frequencies and percentages were calculated for all categorical variables. Spearman’s rho correlation was looked for age, diameter and content of DD.

Results

The normality of the age group studied was checked by histogram, Q-Q plot and found that the age of study group was approximately normally distributed. The prevalence of DD was found to be 8.3% (n = 47). Its prevalence in male was 8.9% (n = 28) and in female was 7.6% (n = 19) showing no sex predilection. Its prevalence increased with age (p < 0.01) and was found predominantly to be in the age group of above 60 years with the prevalence of 15.6% [Table/Fig-1]. Of the DD observed, 89.3% were of solitary and 10.64% were multiple (double).

Distribution of duodenal diverticulum in Indian population assessed using contrast enhanced computed tomography.

| Factors | Prevalence (%) |

|---|

| Overall (n = 565) | 47 (8.3) |

| Sex: |

| Males (n= 314) | 28 (8.9) |

| Females (n= 251) | 19 (7.6) |

| Age: |

| < 12 years (n=7) | 0 (0.0) |

| 13 – 40 years (n = 215) | 9 (4.2) |

| 41 – 60 years (n = 253) | 24 (9.5) |

| > 60 years (n = 90) | 14 (15.6) |

| Number of DD (n = 47) |

| Single | 42(89.3) |

| Multiple | 5 (10.6) |

| Location (n = 52) |

| I part | 0 (0.00) |

| II part | 47 (90.38) |

| PAD | 20 (42.55) |

| JPDD | 25 (53.19) |

| others | 2 (4.26) |

| III part | 5 (9.62) |

| IV part | 0 (0.00) |

| Contents (n = 52) |

| Air | 18 (34.62) |

| Air + fluid | 33 (63.46) |

| Fluid | 1 (1.92) |

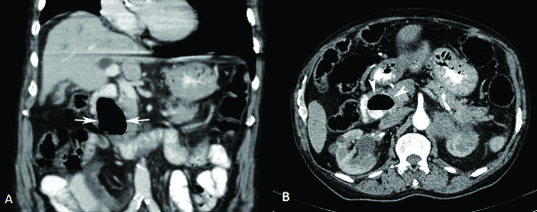

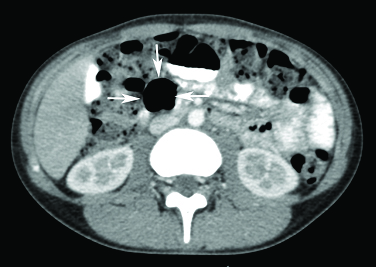

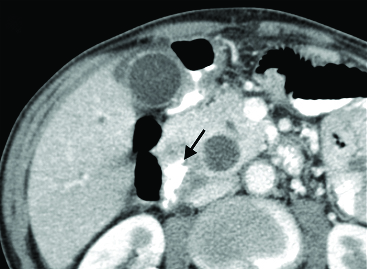

All the diverticulae were found along the inner border of the duodenum. The wall of the diverticulae was thin compared to the thickness of the normal duodenal wall. The diameter of the diverticulae varied from 6mm to 36mm (mean 17.13mm ± 7.26). They were predominantly found in the second part of duodenum (90.38%), of which Juxtapapillary Duodenal Diverticulum (JPDD) was the commonest (53.19%). Diverticulum in the second part of duodenum, 3-4cm away from the major duodenal papilla accounted for 4.26%. The content of the diverticulae was mixture of air and fluid/contrast in 63.46% [Table/Fig-2] followed by air alone in 34.62% [Table/Fig-3] and fluid/contrast alone in 1.92% [Table/Fig-4].

Coronal (A) and axial (B) contrast enhanced computed tomography sections of a 78-year-old man showing a duodenal diverticulum in II part containing contrast-air level (white arrows in A and white arrow heads in B).

Contrast enhanced computed tomography axial section through the abdomen of a 14-year-old girl shows an air filled duodenal diverticulum in the III part (white arrows).

Cropped contrast enhanced computed tomography axial sections of the abdomen of a 74-year-old man shows duodenal diverticulum in II part filled only with contrast (black arrow).

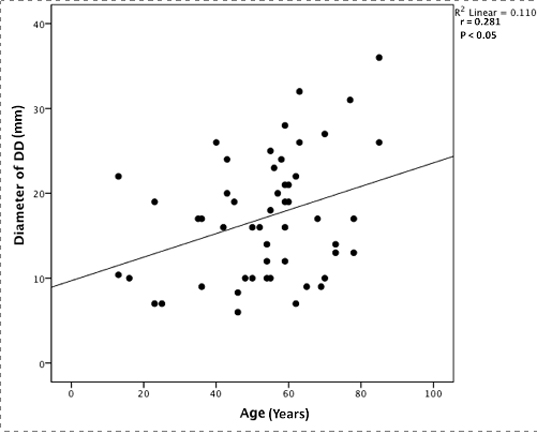

A significant positive correlation was found between age and the diameter of DD (p <0.05) [Table/Fig-5]. As the diameter of DD increased, fluid/contrast became its content. The mean diameter of DD with air alone as content is 14.98 mm, with air and fluid/contrast as content is 18.39mm.

Scatter plot showing a significant positive correlation between age of the patients and diameter of the duodenal diverticulum (DD). Spearman’s rho co-efficient value (r) and p-value are represented in the figure.

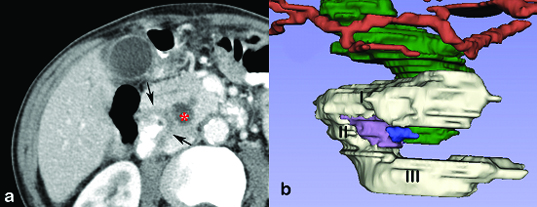

The DD was seen either alone or in association with pancreatitis, cholelithiasis, colonic diverticulum or periampullary carcinoma. But their associations were not found to be statistically significant. In addition, a tumour arising from the wall of the DD was observed in the case of periampullary carcinoma resulting in the dilatation of the common bile duct. For the better visualization of the tumour arising from the wall of DD, 3D reconstruction was created from the segmental contour which was performed on the axial images of CECT abdomen done only for the case of periampullary carcinoma arising from wall of DD using 3D slicer software version 4.4.0 [Table/Fig-6a,b].

(a) Cropped contrast enhanced computed tomography axial sections of the abdomen of a 74-year-old man showing peri-ampullary duodenal diverticulum with contrast alone as the content and nodular thickening of the wall (black arrows) causing distal common bile duct obstruction and upstream dilatation (red *).

(b) A 3D model on the axial images of contrast enhanced computed tomography of abdomen using 3D slicer software. I, II, III – 1st, 2nd and 3rd part of duodenum; purple – duodenal diverticulum; blue – tumour arising from the wall of duodenal diverticulum; green – common bile duct; red- hepatic artery. Note the dilated common bile duct due to the compression of the tumour from the duodenal diverticulum.

Discussion

Diverticulum and their related diseases are common in large intestine. Next to large intestine, it is common in duodenum followed by jejunum, ileum and stomach [11]. Prevalence of DD was reported to be 5.6% in Tehran population [5] and 4.2% in south Indian population [12]. Prevalence of DD in western population based on abdominal CT was found to be 0.46% (n = 12,704) [13]. In our series the prevalence of DD in the Indian population is found to be 8.3% using CECT. This figure is high in comparison with the number reported in a cadaveric study in South Indian population of 4.2% [12]. This can be attributed to the low sample size of the cadaveric study.

The mean diameter of the DD in the present study was 17.13mm ± 7.26 as compared to 14mm in the cadaveric study on South Indian population that was attributed to the shrinkage caused due to embalming [12]. But the average diameter of the DD was found to be 28mm in another radiological study done by Case in 85 samples [14]. Further study has to be done to ascertain whether the reduction in size of the DD in Indian population is due to ethnicity.

Its prevalence increased with age and was found to be rare before third decade of life [15]. Though the occurrence of DD showed no sex predilection [16], female preponderance was reported [17]. But in the cadaveric study in the South Indian population, DD was reported only in the male population [12]. In the present study, DD was noted as early as 13 years of age and showed no sex predilection.

DD is of two types namely, primary or true diverticulum (congenital) and secondary or false diverticulum (acquired). The other way of classifying it is Extraluminal DD (EDD) and intraluminal DD. Of which, EDD are more common and further classified as Periampullary Diverticulum (PAD) and Juxta-Ampullary DD (JPDD). JPDD is defined as DD seen within a diameter of 2cm from the major duodenal papillae and constitutes about 75% of EDD [11]. EDD is common in the second part of duodenum (62%), followed by third part (30%) and fourth part (8%). It is also common along the medial border of duodenum than the lateral border (5%) [18]. In the present study, all the diverticula were of extraluminal type. They were present along the inner border of the duodenum. As reported in the earlier studies, in the present study also DD were common in the second part and JPDD was the commonest (53.19%). A 4.26% of the diverticulum in the second part were 3 – 4 cm away from the papilla and so considered to be of the third variety called “Abpapillary or Fugopapillary type”. The present study has also emphasised on the contents of the DD as the presence of air and fluid in the diverticulum is one of the diagnostic criteria of the DD. Majority of the DD showed both air and fluid (contrast filled).

Etiopathogenesis for the development of DD are: 1) presence of locus minoris resistantiae [19]; 2) weakness or defect in the muscular wall of duodenum; 3) place where the blood vessels or ducts open into the duodenum. It could also be precipitated as a result of abnormality in peristalsis, intestinal dyskinesia and raised intraluminal pressure [6].

Most of the DD are asymptomatic. Only 5% present with clinical symptoms [18]. Major complications of DD include diverticulitis, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute perforation which is rarest and with high mortality of 20% [20], pancreatic or biliary disease, localized abscess and formation of fistula [21,22]. DD also predisposes to the formation of the enterolith (Bezoar) that may cause small bowel obstruction [21,23]. Juxta papillary DD is shown to develop with aging and likely predisposes patients to biliary calculi formation and cholangitis. JPDD is also found to considerably increase the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis, failure of cannulation and recurrence of biliary stone disease [5,15].

DD can attribute to the acute abdomen in the form of perforation diverticulitis, acalculous chloecystitis, pancreatitis, biliary obstruction, acute postprandial discomfort pain [24], solitary DD with enterolith [10]. Differentials to be kept in mind in case of cystic lesion in the head of pancreas include mucinous cystic neoplasm, pseudocyst and DD [25]. When the DD within the head of pancreas is completely filled with fluid, then in CT and MRI it may mimic a cystic neoplasm of the head of pancreas [25,26].

In the present study, in a periampullary DD where contrast alone was the content, its wall showed nodular thickening. It resulted in the dilatation of the common bile duct due to obstruction which could be seen in both the CECT and 3D reconstructed image. Periampullary carcinoma arising from DD is extremely rare and so far only 2 cases were reported [27]. Therefore, though DD is a differential diagnosis for cystic neoplasm of head of pancreas, it should be kept in mind that DD can give rise to periampullary carcinoma of the head of pancreas. Duodenal diverticulitis is rare, yet it can be a cause of acute abdomen mimicking other conditions. The association and the causal relationship of DD with pancreatitis, cholelithiasis, colonic diverticulum and periampullary carcinoma are yet to be studied.

Limitation

The association of DD with pancreatitis, cholelithiasis, colonic diverticulum could not be studied at a statistically significant level as the numbers of cases with these conditions were less in the studied sample size. Though CECT is the current modality of choice for diagnosing DD, in case of children CECT for diagnosing DD is of limited value due to less fat within the abdomen.

Conclusion

The prevalence of DD in Indian population is high compared to western population with no sex predilection. It can also be found in association with pancreatitis, recurrent biliary calculi and cholelithiasis. The radiologist when encountering a cystic lesion in the head of pancreas should be cognizant about the fact that DD with fluid alone as content may mimic a cystic neoplasm of pancreas. The knowledge of DD should be emphasised upon by the gastroenterologists and surgeons while dealing with cases of periampullary carcinoma as such carcinoma can rarely arise from the wall of the pre-existing DD.