Prescription refers to a written order from health professional to a patient. It is one of the significant steps in patient management. The word prescription originates from Latin “pre” meaning before and “scribe” meaning writing [1]. Almost all interactions between doctor and a patient end with prescription writing [2]. Appropriate prescription writing is an integral part of healthcare by which a physician can influence the patient’s health and well-being [3]. A prescription error can be described as “a failure in the prescription writing process that results in a wrong instruction about one or more of the normal features of a prescription” [4]. Errors in prescription usually arise due to careless attitude and hastiness exhibited by some health professionals during prescription writing.

Prescription errors are either ‘errors of omission’ or ‘errors of commission’. A prescription with essential information missing is an ‘error of omission’ whereas a prescription with wrongly written information refers to an ‘error of commission’. Majority of prescriptions are errors of omission that represent irregularities in dosage form, strength, or regimen, and also illegible prescriptions [5]. Prescription errors account for 70% of medication errors that could potentially result in adverse effects [6]. The suboptimal or irrational prescription writing skills can lead not only to therapeutic failure but also to wastage of our resources, adverse clinical consequences and economical harm to both patients and the community [2].

Errors in prescription writing are the most common form of preventable errors and thus an important area for improvement [7]. Good quality prescriptions are known to contribute to improved patient care. With this understanding of importance of quality prescriptions, the current study was conducted to analyze the quality of prescription writing patterns by the students of The Oxford Dental College and Hospital, Bangalore.

The main objective was to identify areas of strengths and weaknesses in prescription writing thereby encouraging health professionals to write a complete legible prescription.

Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted in the Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, The Oxford Dental College and Hospital, Bangalore. A cross-sectional study was carried out on 500 prescriptions written over a period of six months (January to June 2015). Patients exiting various departments in the college after obtaining prescriptions were approached for involvement in the study. The prescriptions were obtained directly from the patient to ensure that the prescribing students remain unaware of the study, so as to avoid bias. Photocopies of prescriptions were then made and retained as sample proof of the study.

Prescriptions obtained were written by students of different qualifications and were thus divided into three groups as those belonging to undergraduates, interns and postgraduates.

A structured evaluation proforma containing 19 parameters for institutional purpose was prepared by referring to various national and international prescription formats [8–12]. The proforma was then used to assess the quality of each prescription as follows (a) Patient’s information: OP number, name, age, gender, address and contact number. (b) Doctors information: Full name, department name, qualification, contact details, date of prescription, superscription and signature. (c) Drug information: Name, strength, dosage form, dosage instruction, duration and total quantity. Scoring of each prescription was done at the end of the proforma according to following criteria: if the parameter was present it was counted as Yes (1) and if parameter was absent than it was counted as No (0). Thus overall 19 parameters were assessed and scored for each prescription. The maximum and minimum scoring was 19 and 0 respectively.

According to the scores obtained, prescriptions were divided into four different groups as follows:

Group A (Poor) - Score 1 to 5

Group B (Fair) - Score 6 to10

Group C (Good) - Score 11 to 15

Group D (Excellent) - Score 16 to 19

The prescriptions were scored and grouped by the corresponding author under the supervision of a professor in our department. Association between the student’s qualification and the groups was done by taking mean score. The results obtained were tabulated and subsequently subjected to statistical tests (Chi – square test and Bonferoni method).

Results

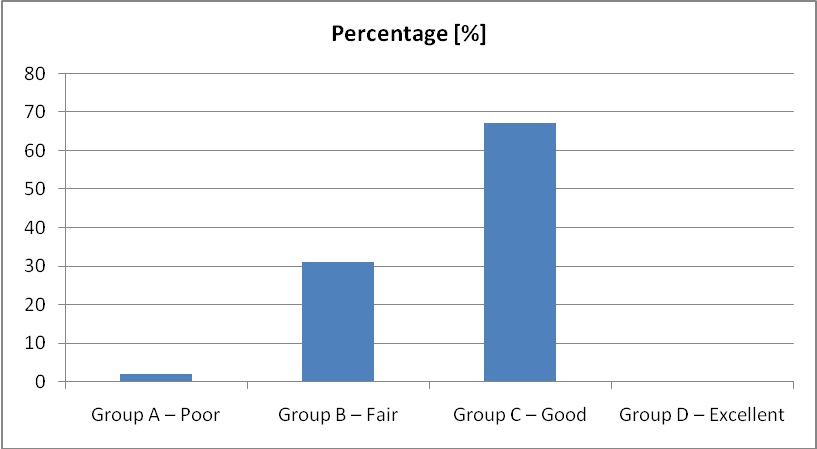

Analysis of quality of prescriptions was done by comparison with a standard format and dividing them into four groups as poor, fair, good and excellent depending upon the score obtained. The results showed that 12 (2%), 155 (31%), 335 (67%) and 0 (0%) prescriptions belonged to groups A, B, C and D respectively [Table/Fig-1].

Analysis of quality of prescription writing amongst students.

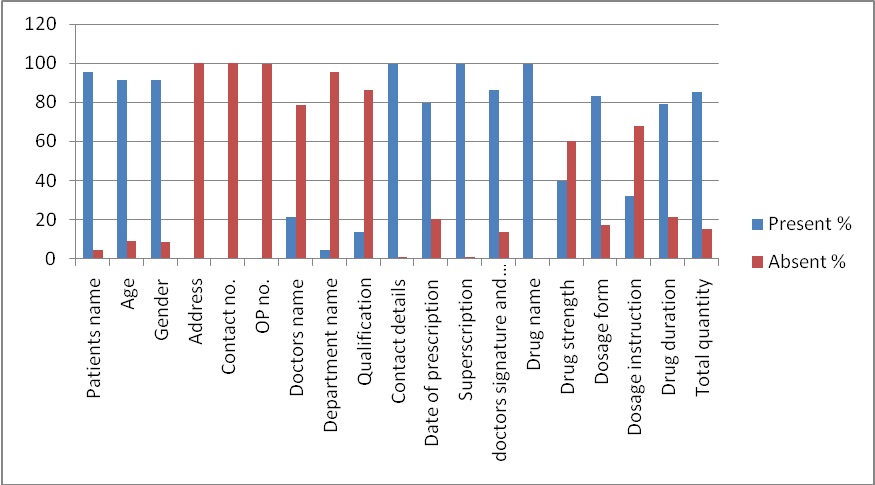

In all the prescriptions, 19 parameters were checked for presence or absence. On analyzing patients information about name, age, gender, address, and OP number, it was written by 478 (95.6%), 456 (91.2%), 458 (91.6%), 2 (0.4%) students respectively. None of the prescriptions had address and contact number [Table/Fig-2]. On analyzing doctors information (Full name, department name, qualification, contact details, date of prescription, superscription, and signature) it was written by 107 (21.4%), 22 (4.4%), 68 (13.6%), 497 (99.4%), 399 (79.8%), 497 (99.4%), and 432 (86.4%) students respectively [Table/Fig-2]. On analyzing drug information (Name, strength, dosage form, dosage instruction, duration and total quantity) was written by 499 (99.8%), 200 (40%), 415 (83%), 161 (32.2%), 395 (79%), 426 (85.2%) students respectively [Table/Fig-2].

Analysis of each parameter of prescription amongst students.

Out of 500 prescriptions, 52 prescriptions were written by undergraduates, 221 by interns and 227 by postgraduates. Association between patient’s information data and doctor’s qualification showed no statistical significant association [Table/Fig-3].

Comparison between patient’s information parameters and qualification of students.

| Patient Information | Result | UG Student (n=52) | Intern (n=221) | PG Student (n=227) | χ2 | p-value |

|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

|---|

| Patients Full Name | Absent | 1(2%) | 11(5%) | 10(4%) | 0.934 | 0.627 |

| Present | 51(98%) | 210(95%) | 217(96%) |

| Age | Absent | 2(4%) | 22(10%) | 20(9%) | 1.957 | 0.376 |

| Present | 50(96%) | 199(90%) | 207(91%) |

| Gender | Absent | 2(4%) | 21(10%) | 19(8%) | 1.751 | 0.417 |

| Present | 50(96%) | 200(90%) | 208(92%) |

| Address | Absent | 52(100%) | 221(100%) | 227(100%) | --- | --- |

| Present | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) |

| Contact No. | Absent | 52(100%) | 221(100%) | 227(100%) | --- | --- |

| Present | 0(0%) | 0(0%) | 0(0%) |

| OP No. | Absent | 52(100%) | 220(100%) | 226(100%) | 0.233 | 0.890 |

| Present | 0(0%) | 1(0%) | 1(0%) |

Statistical analysis for the association between doctor’s information and qualification showed significant association (p<0.05) in doctor’s full name (p<0.001), doctor’s qualification (p<0.001) and doctor’s signature (p=0.016) [Table/Fig-4].

Comparison between doctor’s information parameters and the qualification of students.

| Doctor Information | Result | UG Student (n=52) | Intern (n=221) | PG Student (n=227) | χ2 | p-value |

|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

|---|

| Doctor’s full name | Absent | 15 (29%) | 191 (86%) | 187 (82%) | 86.501 | <0.001* |

| Present | 37 (71%) | 30 (14%) | 40(18%) |

| Department name | Absent | 52 (100%) | 214 (97%) | 212 (93%) | 5.822 | 0.054 |

| Present | 0 (0%) | 7 (3%) | 15 (7%) |

| Qualification | Absent | 13 (25%) | 200 (90%) | 219 (96%) | 189.606 | <0.001* |

| Present | 39 (75%) | 21 (10%) | 8 (4%) |

| Contact details | Absent | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 1 (0%) | 0.755 | 0.685 |

| Present | 52 (100%) | 219 (99%) | 227 (100%) |

| Date of prescription | Absent | 6 (12%) | 49 (22%) | 46(20%) | 2.954 | 0.228 |

| Present | 46 (88%) | 172 (78%) | 181(80%) |

| Super-scription | Absent | 0 (0%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0.755 | 0.685 |

| Present | 52 (100%) | 219 (99%) | 226 (100%) |

| Doctor’s signature & date | Absent | 1 (2%) | 39 (18%) | 37 (16%) | 8.247 | 0.016* |

| Present | 51 (98%) | 182 (82%) | 190 (84%) |

*denotes significant association

Comparison between drug information and qualification showed statistical significant association for strength of the drug (p=0.032), dosage form (p=0.040), dosage instruction (p= 0.001) and total quantity of drugs (p=0.005) [Table/Fig-5].

Comparison between drugs information parameters and the qualification of students.

| Drug’s Information | Result | UG Student (n=52) | Intern (n=221) | PG Student (n=227) | χ2 | p-value |

|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

|---|

| Name of the drug | Absent | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1(0%) | 1.205 | 0.547 |

| Present | 52(100%) | 221(100%) | 226(100%) |

| Strength of the drug | Absent | 35(67%) | 143(65%) | 122(54%) | 6.897 | 0.032* |

| Present | 17(33%) | 78(35%) | 105(46%) |

| Dosage form | Absent | 3(6%) | 36(16%) | 46(20%) | 6.442 | 0.040* |

| Present | 49(94%) | 185(84%) | 181(80%) |

| Dosage instruction | Absent | 27(52%) | 167(76%) | 145(64%) | 13.709 | 0.001* |

| Present | 25(48%) | 54 (24%) | 82(36%) |

| Duration of drug | Absent | 6(12%) | 48(22%) | 51(22%) | 3.169 | 0.205 |

| Present | 46(88%) | 173(78%) | 176(78%) |

| Total quantity of drug | Absent | 2(4%) | 27(12%) | 45(20%) | 10.661 | 0.005* |

| Present | 50(96%) | 194(88%) | 182(80%) |

*denotes significant association

Comparison between groups and qualification showed statistical significant results. Out of 52 undergraduates, Groups B and C had 4 (8%) and 48 (92%) students respectively. Out of 221 interns, groups A, B, and C had 4 (2%), 81 (37%), and 136 (62%) interns respectively. Out of 227 postgraduates, groups A, B, and C, had 8 (4%), 70 (31%), 149 (66%) students respectively [Table/Fig-6].

Comparison between groups and qualification of students.

| Group | UG Student (n=52) | Intern (n=221) | PG Student (n=227) | χ2 | p-value |

|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Group A | 0(0%) | 4(2%) | 8(4%) | 20.197 | <0.001* |

| Group B | 4(8%) | 81(37%) | 70(31%) |

| Group C | 48(92%) | 136(62%) | 149(66%) |

*denotes significant association

Comparison of mean score between the qualifications showed higher mean score in undergraduate students followed by postgraduate students and interns respectively. The difference in mean score among the groups was found to be statistically significant (p<0.001) [Table/Fig-6].

In order to find out existence of significant difference amongst the different groups; we carried out multiple comparisons using Bonferoni method. The difference in mean score was found to be statistically significant between undergraduate students and interns (p<0.001) as well as between undergraduate and postgraduate students (p<0.001). No significant difference was observed between interns and postgraduate students (p>0.05) [Table/Fig-7].

Multiple comparisons using bonferoni method between pair of groups.

| (I) Prescriptionwritten by | (J) Prescriptionwritten by | MeanDifference(I-J) | p-value | 95% CI for Mean Diff |

|---|

| LowerBound | UpperBound |

|---|

| UG Student | Intern | 2.117 | <0.001* | 1.39 | 2.85 |

| PG Student | 1.928 | <0.001* | 1.20 | 2.66 |

| Intern | UG Student | -2.117 | <0.001* | -2.85 | -1.39 |

| PG Student | -0.188 | 0.938 | -0.64 | 0.26 |

| PG Student | UG Student | -1.928 | <0.001* | -2.66 | -1.20 |

| Intern | 0.188 | 0.938 | -0.26 | 0.64 |

*denotes significant difference

Discussion

Prescription of medications is the most common form of treatment. Errors in prescription writing do occur leading to significant patient morbidity and mortality. A study conducted by Ingrim et al., on 7858 prescriptions revealed errors in 1070 prescriptions (13.6%)this was in contrast to a study conducted at a government hospital in Indonesia in which prescription errors noted were really high (99.1%) [13,14].

In the current study, analysis of prescriptions revealed that patient’s name (95.6%), age (91.2%) and gender (91.6%) was written by majority of the students. Patient’s outpatient number (0%), address (0%), and contact number (0.4%) was missing in almost all the prescriptions. Patient’s information is very important to record so as to ensure that the correct medication goes to the proper patient and also for identification and record maintenance. The low level of entries with respect to these parameters may be due to clinical work load or due to the fact that the information is already recorded in the patient register or case sheets.

A similar study conducted in Nigeria to assess the quality of prescription in a tertiary care hospital showed that the age of the patients was recorded as adult in most of the prescriptions instead of specific age. However, patient identifier (name, hospital number and address) was present in majority of collected prescription [4].

Babar et al., conducted a study on 206 prescriptions to assess the quality of prescription writing, patients name and age was present in 180 (87%) and 115 (55%) prescriptions respectively [15].

In the current study, data collected from doctor’s information revealed that almost all the prescriptions contained contact details (99.4%) and superscription (99.4%). Doctor’s qualification (13.6%) and department name (4.4%) was missing in majority of the prescription. Doctor’s information is necessary to allow the patient or pharmacist to contact the doctor for any clarification. Moreover, absence of prescriber signature would also invalidate the prescription and cause inconvenience to the patient and the staff involved.

A similar study conducted by Rathnam et al., in KLE Institute of Dental Sciences, Belgaum showed that doctors information such as signature and departments name was lacking in most of the prescriptions whereas doctors name and contact number were present in majority of the prescriptions [16].

In the current study, data collected about drug information revealed that the parameters which were lacking the most were dosage instructions, strength of the drugs, and duration of the drugs [Table/Fig-1]. Antibiotics and analgesics were the most commonly prescribed drugs, amoxicillin and diclofenac sodium being the most commonly prescribed antibiotic and analgesic respectively. Also, brand names of the drugs were written instead of generic names in majority of prescriptions. It is advisable to prescribe medicines by generic names in order to make prescriptions simple, clear and economical [17].

Tamuno I et al., conducted a study on 497 prescriptions. The study revealed that generic drug prescribing was performed in only 42.7% of the prescriptions [18]. Similar study by Alagoa PJ et al., showed a total of 740 drugs being prescribed in 225 prescription notes, out of which generic name of drugs were written for 53% of the prescribed drugs [19]. A study by Sultana et al. on 978 prescriptions revealed errors in 769 prescriptions. Strength of the drug was missing for 279 drugs and 31 drugs were abbreviated, wrongly [20].

A study conducted by Bhosale et al., for analysis of completeness of prescription in a tertiary care hospital involved 400 prescriptions. The study showed that hospital identification and prescriber details like name and signature were present in majority of prescriptions [7].

Prescriptions in the current study were divided into four groups according to the scores obtained from the structured proforma, as Group A (Poor), Group B (Fair), Group C (Good) and Group D (Excellent) with the highest number of prescriptions belonging to group C (Good). Analysis for association between groups and qualification showed significant association (p<0.001) [Table/Fig-6]. Comparison of mean scores between the qualifications showed higher mean score in undergraduate students followed by postgraduates and interns, the mean score being statistically significant. Undergraduate student’s prescriptions were better written when compared with postgraduates and interns, as undergraduates were trained and supervised by staff in the respective departments in which they were posted. Interns prescriptions writing was the poorest in comparison with other groups due to negligence.

A study conducted in Nepal by Kumar J et al., to compare the quality of prescription writing skills between first year and second year medical students showed that the overall performance of second year medical students was better than that of first year students [2].

Legibility assessment is quite subjective and thus may be biased in the study. Whether a prescription is legible or not depends on the assessor’s familiarity with the handwriting of the prescriber as well as information provided in the prescription, thus we didn’t include legibility criteria in our study to avoid bias in the study [6]. It is also a matter of concern that most of the instructions given to the patients about the use of medication for oral or topical medication was verbal, so there are more chances of errors as it depends on patients understanding, the doctors communication and the language barrier between both, hence clear instructions should be written in the prescriptions to avoid errors [17].

A study on prescription patterns of general practitioners in Peshwar, Pakistan by Raza U et al., revealed poor quality of prescription writing due to lack of one or more essential components [21]. Similarly in the present study on analysis of the prescriptions, one or the other parameters were missing indicating that prescription writing quality of our institution needs to be improved.

Limitation

The current study with a sample size of 500 prescriptions provides an insight to quality of prescription writing in a single institution. Studies with a larger sample size in multiple health centers are recommended to provide more accurate understanding of prescribing patterns in a wider population.

Conclusion

The findings of the current study demonstrate the need for further improvement in the quality of prescription writing by the students of The Oxford Dental College and Hospital, Bangalore. The art of writing excellent quality prescriptions should be taught by medical faculties who are adequately trained in prescription writing. Other strategies recommended to improve quality of prescriptions include clinical governance, use of electronic computerized system of prescribing and continuing professional educational programs.

*denotes significant association

*denotes significant association

*denotes significant association

*denotes significant difference