Evaluation of the Factors and Treatment Options of Separated Endodontic Files Among Dentists and Undergraduate Students in Riyadh Area

Samah Samir Pedir1, Abeer Hashem Mahran2, Khaled Beshr3, Kusai Baroudi4

1 Lecturer, Department of Restorative Dental Sciences, Al Farabi Colleges - Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

2 Professor, Department of Restorative Dental Sciences, Ain Shams UniversityCairo - Egypt; Professor of endodontic – Restorative Department –Al Farabi Colleges - Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

3 Assistant Professor, Department of Restorative Dental Sciences, Al Farabi Colleges - Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

4 Associate Professor, Department of Preventive Dental Sciences, Alfarabi Colleges, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Kusai Baroudi, Associate Professor, Department of Preventive Dental Sciences, Alfarabi Colleges, Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

E-mail: d_kusai@yahoo.co.uk

Introduction

Separation of endodontic files during root canal treatment is a common multifactorial problem facing most of dental practitioners both dentists and students that has high impact on treatment and prognosis outcome.

Aim

To compare the incidence, factors and treatment options of separated endodontic files among dentists and undergraduate students in Riyadh area.

Materials and Methods

A survery of 35-questionnaire was formulated and e-mailed to all 149 dentists of different dental specialties who are working in different clinical centers in Riyadh area and are attending the 26th Saudi Dental Society International Dental Conference in addition to 130 undergraduate students in different dental colleges in Riyadh. Overall, 118 participants of dentists completed the survey, with response rate of 79% and the same number of students with response rate of 90.7%.

Results

Total of 57.6% dentists’ faced separated files problem during root canal preparation, while only 7.6% of students faced this problem. 53% of separated endodontic files (SEF) were hand files, 65% stainless steel files, 81% were small size files most common sizes (#15-20) (p <0.0001). Causes of SEF were root Canal anatomy, in 45%. 66% of SEF occurred in curved canals, 98% were in molars in mesiobuccal and mesiolingual canals, (p <0.0001). 44% of SEF were successfully bypassed, 53% were successfully removed from coronal third of root canal, 42% of SEF successfully removed using ultrasonics under visualization of operating microscope. 73% of retained SEF cases showed good prognosis, (p <0.0001).

Conclusion

SEF is a multifactorial clinical problem that must be either removed, by passed to allow complete cleaning, shaping, disinfection, obturation and effective coronal seal.

Broken, Management, Mishaps, Prognosis, Ultrasonic

Introduction

Clinicians always face procedural errors during root canal preparation. One of these errors is the separation of endodontic instruments within root canal [1]. The incidence of separated instruments in the previous literature ranges from 0.5% to 5% of the cases investigated [2]. A retained Separated Endodontic Files (SEF) impact treatment outcome and obstacle mechanical and chemical treatment of a root canal [3].

The most common causes for SEFare root canal anatomy, improper use, inadequate access, manufacturing defects, limitations in physical properties, and insufficient knowledge about the root canal morphology and its variations [4]. Both nickel-titanium (Ni-Ti) hand and rotary files used currently for root canal instrumentation due to their greater flexibility than stainless steel files so they offer distinct clinical advantages in curved root canals [5–8]. Regardless of the favourable qualities Ni-Ti instruments, there has been an unfortunate increase in the occurrence of broken instruments [9]. Stainless steel instruments commonly fail by excessive torque while Ni-Ti rotary files usually fracture by torsional stress and cyclic fatigue [10].

Divergent to the popular belief; Ni-Ti instruments are of equal fragility as stainless steel instruments of the same size, as there are many radiographic documented reports before 1991 showed remnants of endodontic instruments (stainless steel files, Lentulos, thermocompactors, reamers, etc) left in root canals long before the introduction of rotary Ni-Ti instruments. Until now there no studies clearly reveal that the number of fractured instruments increased since the execution of rotary Ni-Ti instrumentation [11].

Before managing a separated instrument either by removal of the fractured segment, bypassing and sealing the fragment within the root canal space or true blockage we should properly assess the pulp status, root canal infection, root canal anatomy, position and type of fractured instrument and the amount of damage that would be caused to the remaining tooth structure should be considered [12].

Recent technological advancements as ultrasonic and micro tube methods allow easy removal of separated instruments [13,14]. The dental operating microscope allows clinicians to visualize most broken instruments [15].

The diameter, length and position of the obstruction within a canal and the type of the metallic object influence the non-surgical access and removal of a broken instrument. Nonsurgical removal usually cannot be accomplished when the entire segment of the broken instrument is apical to the curvature so that safe access with visualization is not possible [16,17].

Traditional retrieval techniques evolved but were ineffective because of limited vision and/ or restricted space. Leaving a fractured instrument inside the root canal with incomplete obturation or ineffective coronal seal may lead to micro-organisms penetration inside the canal developing periapical lesion and so treatment failure [18,19].

Aim

The aim of this study was to compare results of the incidence and factors contributing to separated endodontic files between dentists and undergraduate students as well as to analyse the results of treatment options, management mishaps and prognosis of SEF during endodontic treatment among dentists in Riyadh area.

Materials and Methods

A pilot survey was sent to a group of local dentists whose feedback was incorporated into the final 35-questions survey. An invitation to participate in the online survey was e-mailed to all 149 dentists from different dental specialties, working in different clinical centers in Riyadh and are attending 26th Saudi Dental Society International Dental Conference and 130 undergraduate students from different Dental Colleges in Riyadh. The study was conducted in Alfarabi College with ethical approval number 236/2015, consent was obtained from the participants.

This survey was divided into 3 categories in the following order [Table/Fig-1]:

| Baseline demographics |

|---|

| What is your gender?- Male- Female |

| What is your current professional status?- Register- Consultant- G.P |

| How many years have you been practicing dentistry?- less than 3 years- 5-10 years.- More than 10 years. |

| Part I |

| Incidence of SEF and behavior questions: |

| 1. Did you ever break instrument during root canal treatment?- Yes- No | 5. Will you inform your patient and refer him to another specialist?- Yes- No |

| 2. If you break an instrument will you inform your patient?- Yes- No | 6. Wouldn’t you inform your patient and complete treatment?- Yes- No |

| 3. Will you inform your patient and complete treatment in another appointment?- Yes- No | 7. Wouldn’t you inform your patient and not remove the instrument?- Yes- No |

| 4. Will you inform your patient and complete treatment in the same visit?- Yes- No | 8. Do you think that instrument breakage will impact root canal treatment?- Yes- No |

| Factors contributing to SEF |

| 9. Which types of files frequently break with you?- Rotary files- Hand files | 14. Related to the cause of breakage, is it due to?- Root canal anatomy-Improper use- Wrong file motion- Manufacturing errors- Dentist experience |

| 10. Which alloy of manufacture is frequently broken?- Stainless steel- Ni-Ti | 15. If file breakage related to root canal anatomy, what is the most common cause?- Narrow canal-Curved canal- Calcified canal |

| 11. Which sizes are more broken?- Small- Large | 16. In which teeth instruments break more?- Incisors- Canines- Premolars- Molars |

| 12. In which part of root canal the instruments more separate?- Apical- Middle- Coronal | 17. If it is molars, in which root canal is more instrument breakage?- Mesiobuccal canal- Mesiolingual canal- Distobuccal canal- Palatal canal- Distal canal |

| 13. In which stage of root canal treatment instruments are more separate?- While negotiating the canal- During cleaning and shaping- After cleaning and shaping | 18. What will you do to deal with this separated instrument?- Leave it- Bypass- Remove- Refer to specialist |

| Part II: Treatment options results |

| 19. If you will try to bypass it, in which third of root canal could you successfully bypass?- Coronal- Middle- Apical | 23. Will you try to remove the separated instrument?- Yes- No |

| 20. Which size of the separated instrument could you easily bypass?- Small- Large- Mention size……………… | 24. If you will try to remove it, in which third of root canal could you successfully remove?- Coronal- Middle- Apical |

| 21. Which size of instrument could help you for easily bypassing?- Small- Large- Mention size……………. | 25. Which method will help you more in removing the separated file?- Masseran kit - Ultrasonics under the visualization of an operating microscope - Conventional methods- Special device |

| 22. While attempting to bypass separated file, which procedure error results?- Over enlargement of canal- Ledge formation- Canal irregularities- Apical transportation- Perforation- Mention error…………………. |

| Management mishaps |

| 26. While attempting to bypass separated file, which procedure error results?- Over enlargement of canal- Ledge formation- Canal irregularities- Apical transportation- PerforationMention error…………………. | 28. While trying to remove the separated instrument, which procedure error results in root canal?- Over enlargement of canal- Ledge formation- Canal irregularities- Apical transportation- PerforationMention error………………….. |

| 27. If any error produced while attempting to bypass, what will you do?- repair this error and complete bypassing procedure- repair this error and stop bypassing procedure | 29. If any error produced while attempting to remove the separated instrument, what will you do?- repair this error and complete removal procedures- repair this error and stop removal procedures |

| Follow up and prognosis: |

| 30. If you will leave the separated instrument, will you follow up the case?- Yes- No | 33. If it is poor prognosis, what was the periapical tissue state?- Within normal - Periodontitis- Periapical abcess- Loss of lamina dura continuity |

| 31. If you followed up, what results do you found?- Poor prognosis with treatment failure- Good prognosis- It depend on multiple factors | 34. If it is poor prognosis, in which stage was the root canal treatment?- While negotiating the canal- During cleaning and shaping- After cleaning and shaping |

| 32. If it is poor prognosis, what was the previous pulp state?- Vital- Non-vital | 35. If it is poor prognosis, in which canal third was the separated instrument?- Coronal- Middle- Apical |

Baseline demographic

Part I (18 comparison questions for both dentists and students): divided into-

(A) Incidence of SEF and behaviour,

(B) Factors contributing to SEF.

III Part II (17questions only for dentists) divided into-

(A) Treatment options,

(B) Management mishaps,

(C) Follow-up and prognosis.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS software is used for this simple statistical analysis. Chi-square test and one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) at the significance level of α=0.05 were performed to compare between results of questions (1-18) of postgraduate dentists and undergraduate dental students and analysing all results of remaining 17 questions for dentists only in Riyadh area all results are highly significant (p<0.0001).

Results

One hundred eighteen out of one hundred forty nine dentist of different responded to the survey, representing a 79% response rate and the same number of students out of 130 responded also representing 90.7% response rate. 75% of dentist participants were females.

Results of demographic data, current professional status and experience years are presented in [Table/Fig-2]. The difference between genders was statistically significant (p < 0.0001)

Baseline Demographics (n=118).

| Gender | Male | (n=29) | 25% |

|---|

| Female | (n=89) | 75% |

| Professional status | Register | (n=52) | 44% |

| Consultant | (n=13) | 11% |

| G.P | n=53) | 45% |

| Experience/years | >3years | (n=26) | 22% |

| 5-10years | (n=23) | 19% |

| <10years | (n=69) | 59% |

Part I: Comparing first 18 questions answered by dentists and students

Incidence of SEF and behaviour:

– The results of this part of study is presented in [Table/Fig-3]

– Chi-square value shows a statistical significant difference was found when compare between dentist and student answers (p-value < 0.0001).

Factors contributing to SEF:

– We statistically compare answers of the dentist with students’ answers. The results were statistically significant at p-value (p < 0.0001). Also, the different answers within same questions were statistically compared (p < 0.0001).

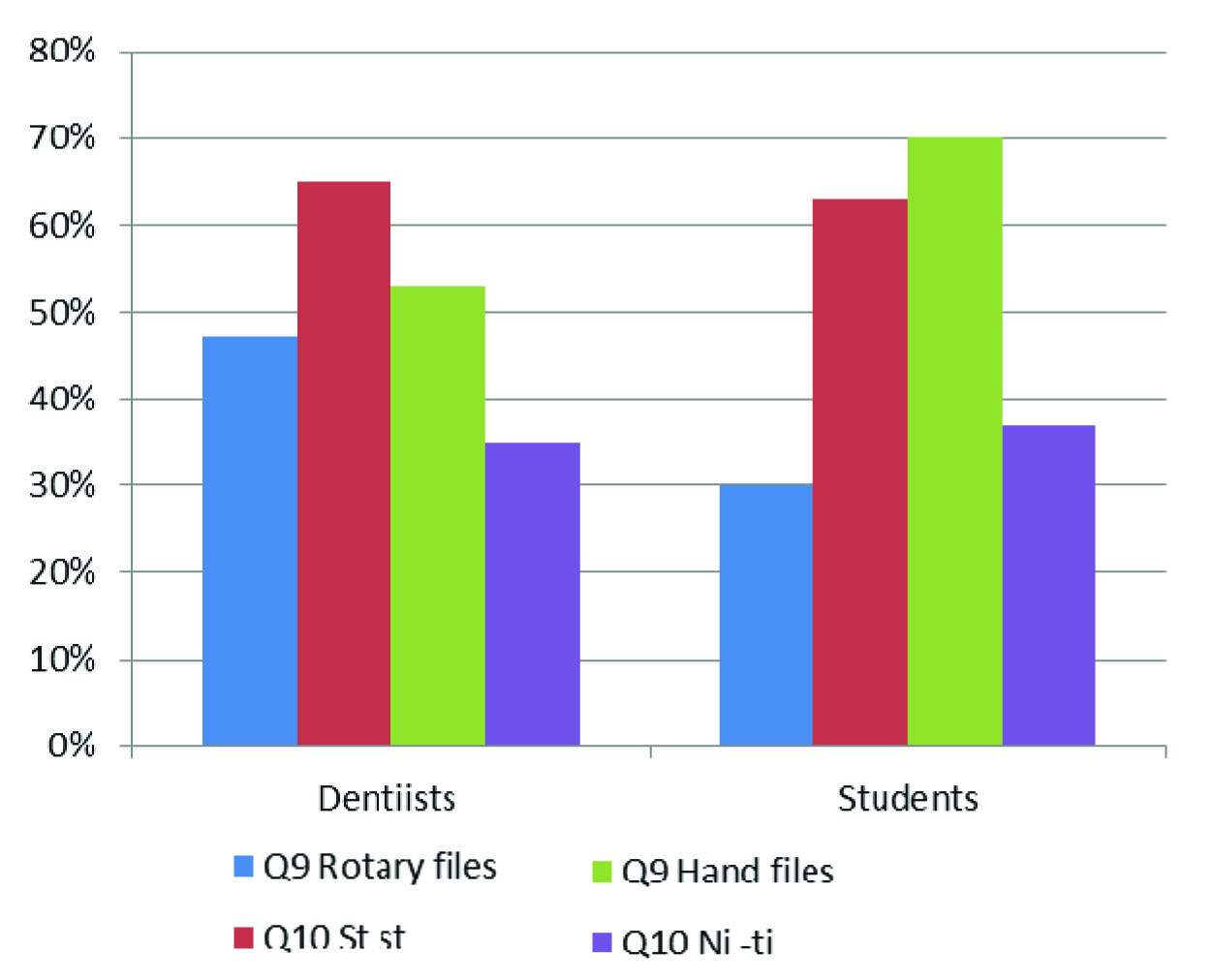

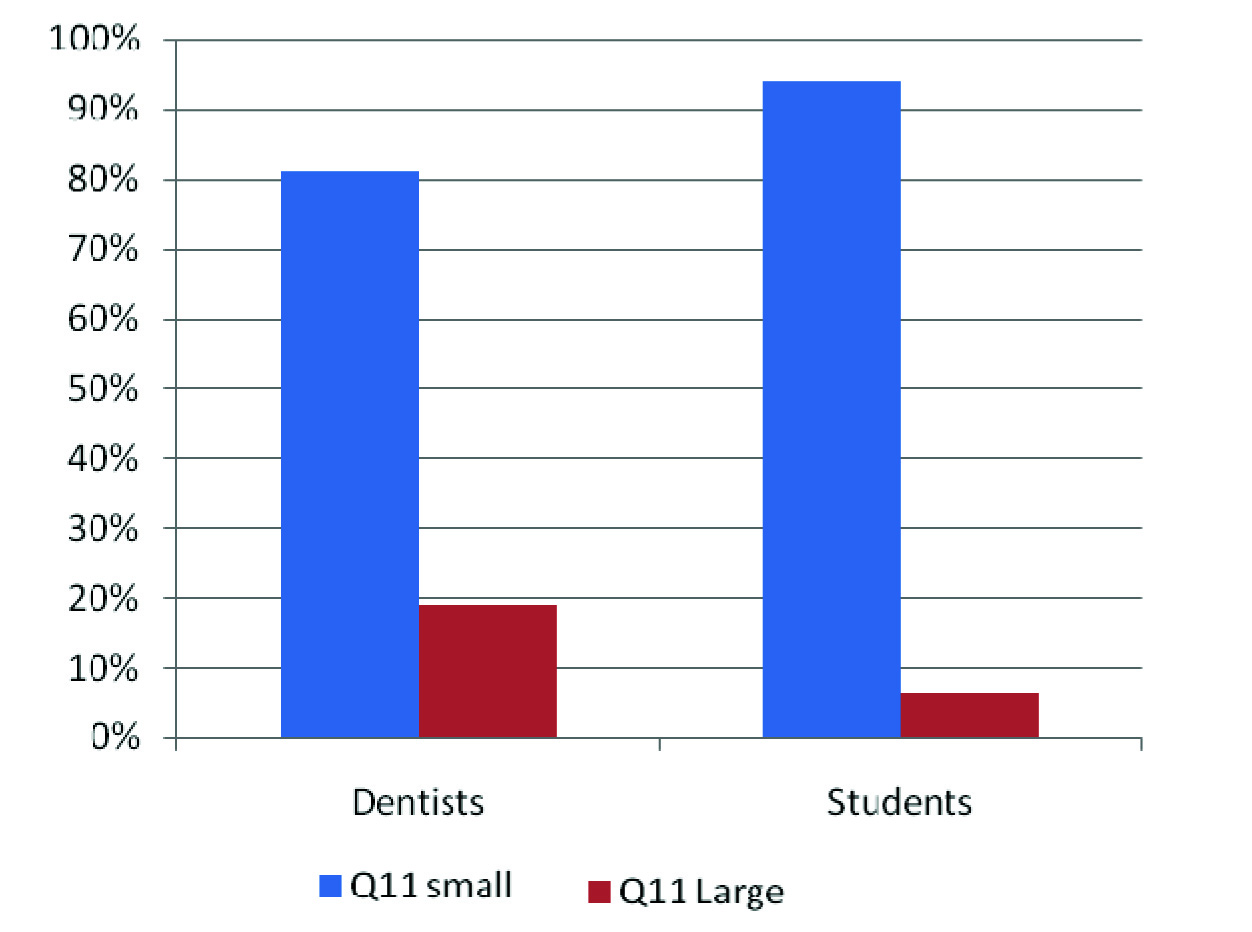

– Concerning dentist answers- 53%, of broken files was hand files, 65% stainless steel files, [Table/Fig-4] and regarding size 81% small size files most commonly (#15-20) [Table/Fig-5].

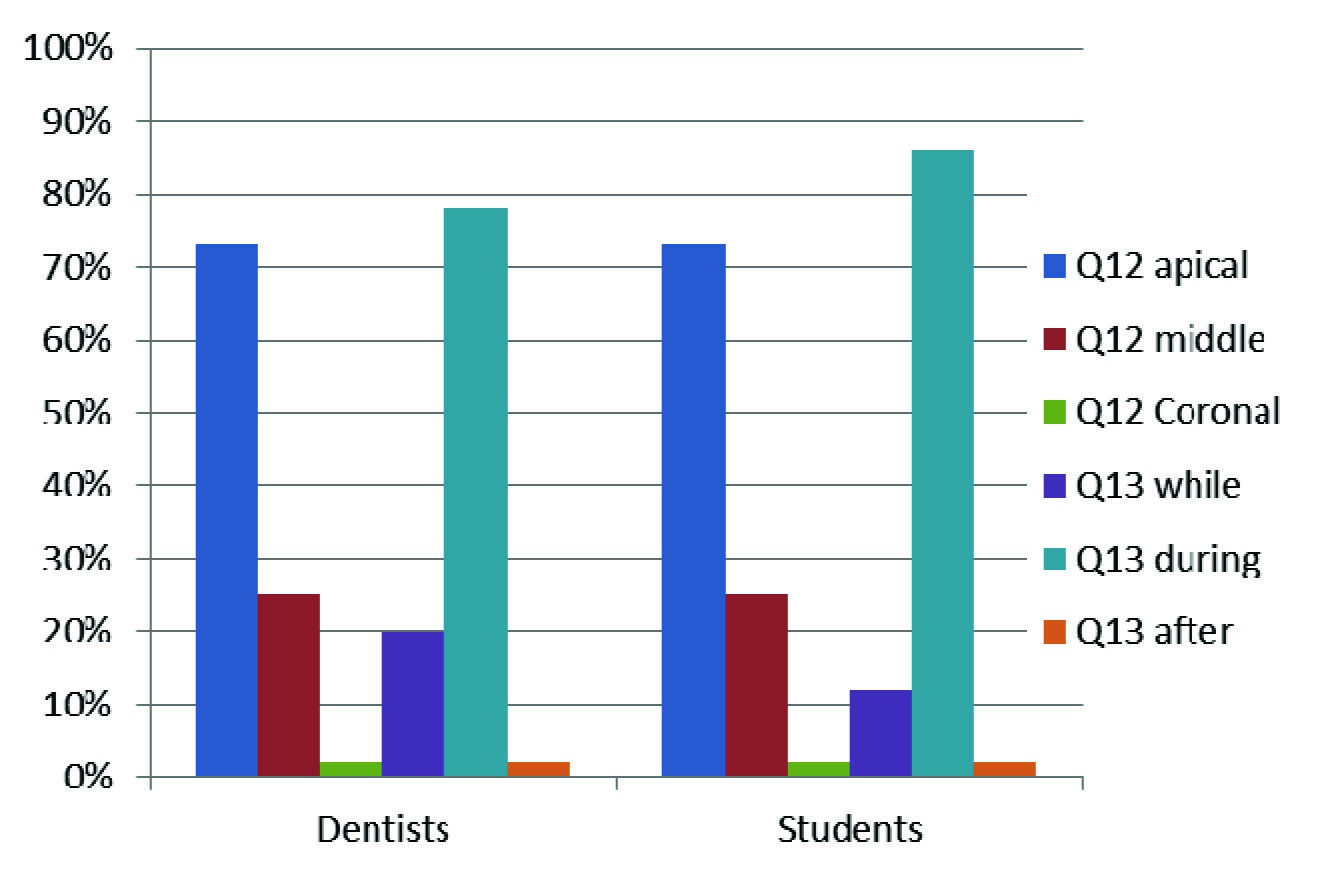

– Concerning the site significantly higher percentage was separated in apical third.

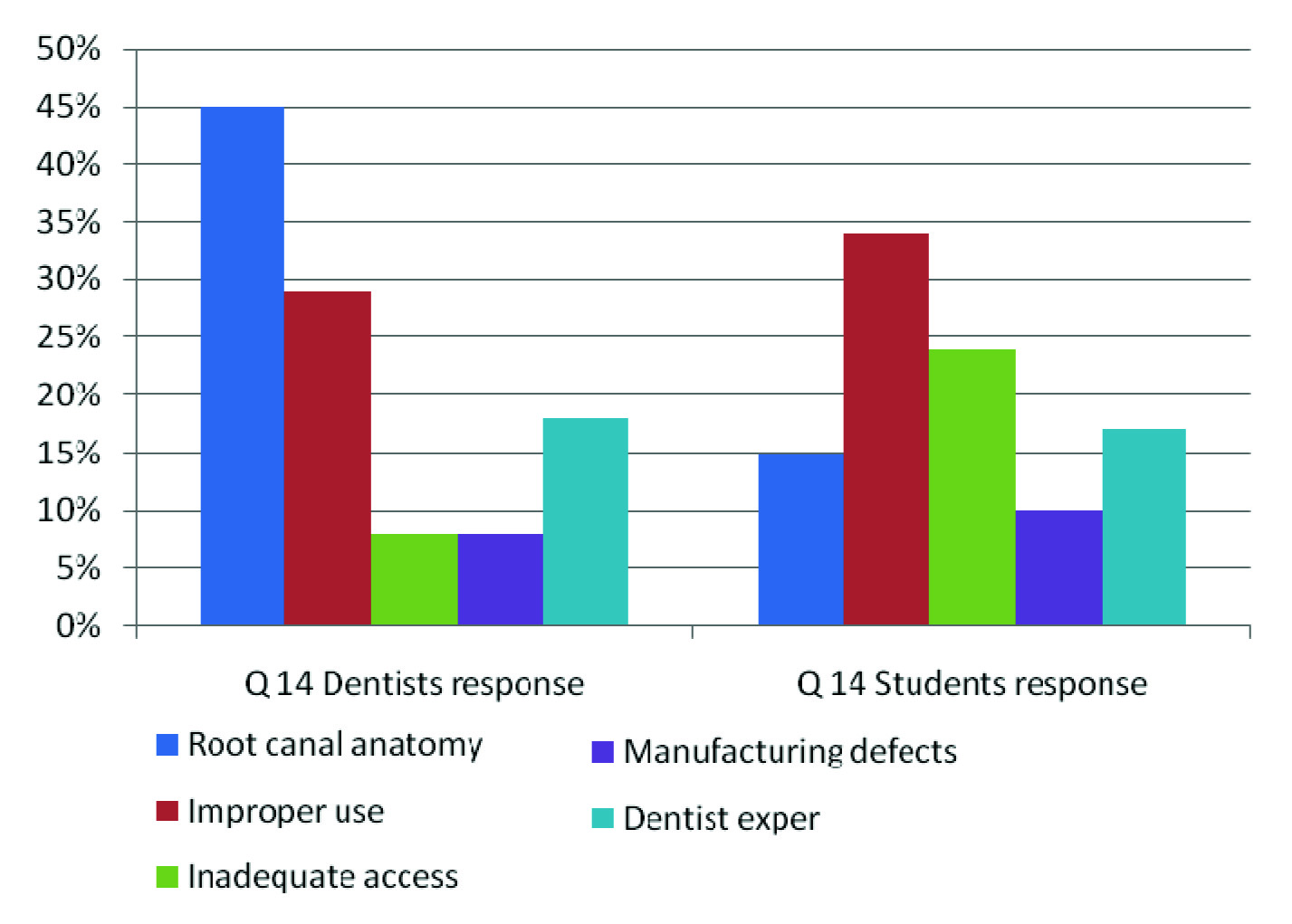

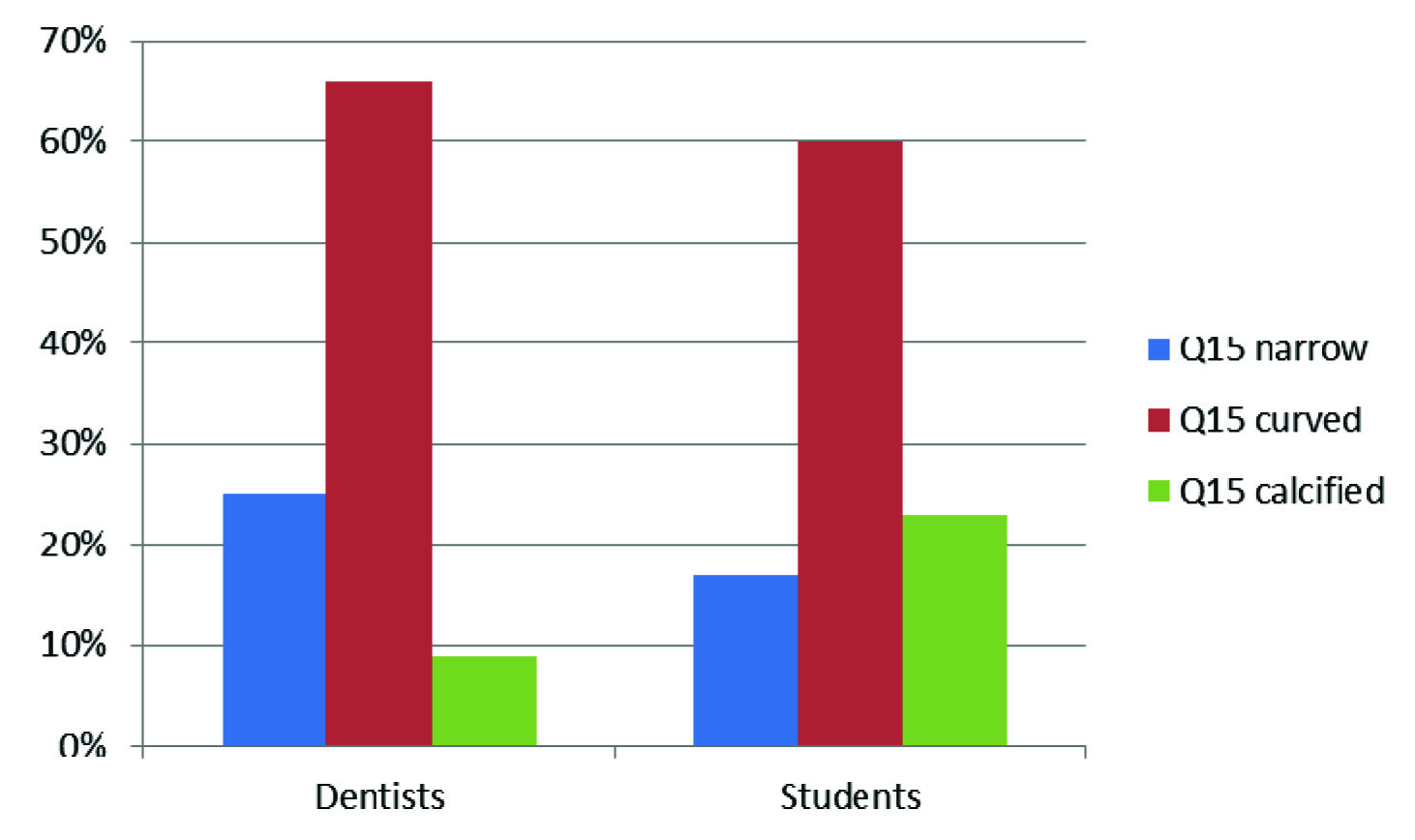

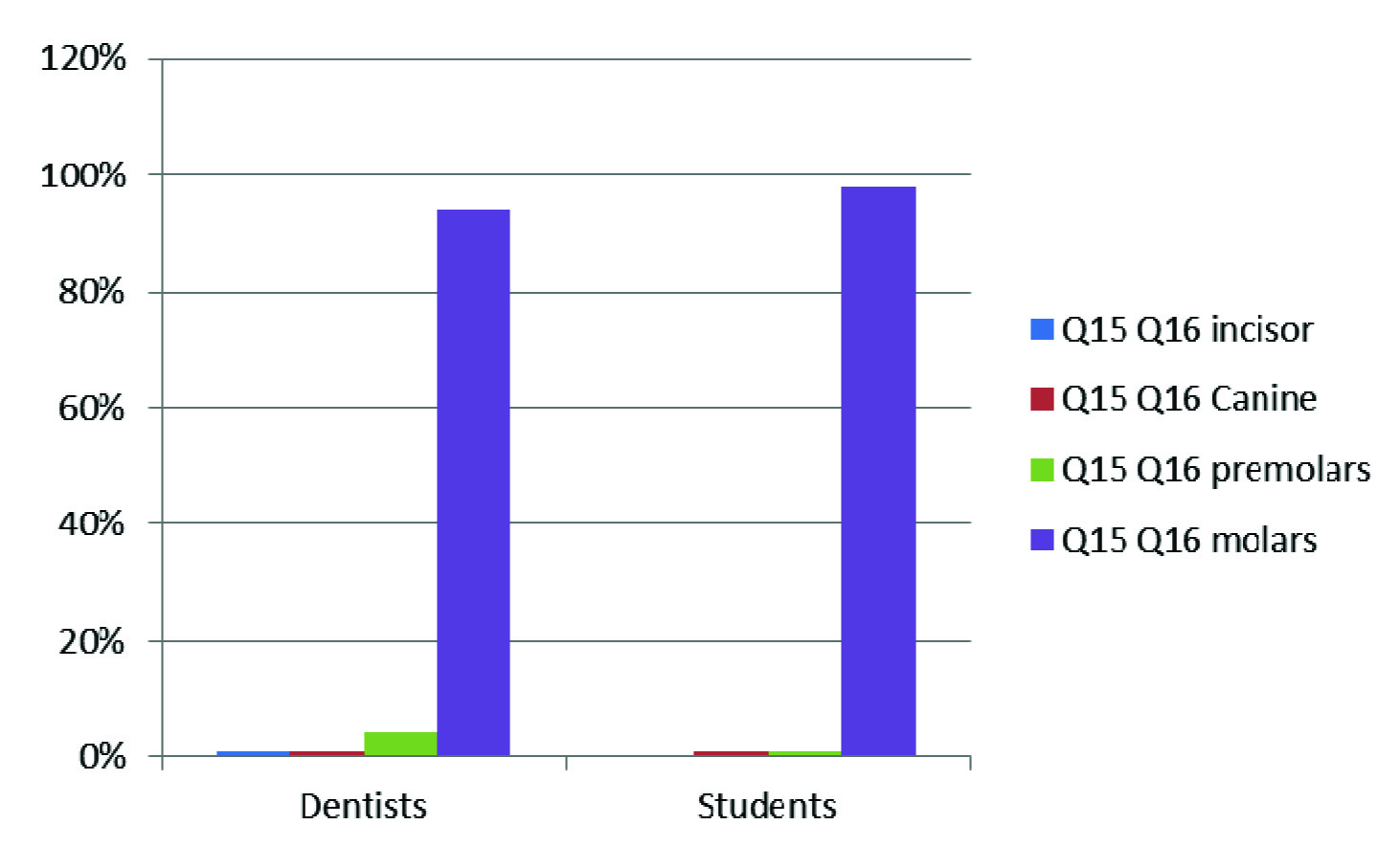

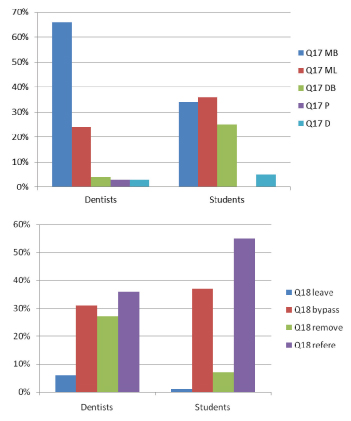

– While 78% significantly broken during cleaning and shaping [Table/Fig-6]. As regard different opinion concerning causes statistically significant results as follows, 45% of breakage due to root canal anatomy [Table/Fig-7], and 66% of curved canals [Table/Fig-8] most commonly were in molars by 94% [Table/Fig-9] especially in mesiobuccal canal 66% [Table/Fig-10].

– Students answers- regarding file type significantly 70% was of hand files, 63% stainless steel [Table/Fig-4], and 94% of small size most commonly (#15-20). [Table/Fig-5] Statistically significant higher percentage were in apical third by 73%, while 86% during cleaning and shaping stage [Table/Fig-6].

– Statistically significant 15% of breakage cases were due to root canal anatomy, [Table/Fig-7] 60% curved canals [Table/Fig-8] significantly molars by 94% [Table /Fig-9] and in mesiolingual 36% [Table/Fig-10].

Incidence of SEF and behaviour (n=118).

| Dentists | Students | Chi-square value |

|---|

| Break files during RCT. | Yes(n=68) 57.6%No(n=50) 42.4% | Yes(n=9) 7.6%No(n=109) 92.4% | 7.164** |

| Inform patient. | Yes(n=103) 87%No(n=15) 13% | Yes(n=116) 98%No(n=2) 2% | 13.97** |

| Inform patient and complete treatment in another appointment. | Yes(n=70) 59%No(n=48) 41% | Yes(n=69) 58%No(n=49) 42% | 113.941** |

| Inform patient and complete treatment in the same visit. | Yes(n=64) 54%No(n=54) 46% | Yes(n=78) 66%No(n=40) 34% | 71.719** |

| Inform patient and refer to specialist. | Yes(n=66) 56%No(n=52) 44% | Yes(n=105) 89%No(n=13) 11% | 18.543** |

| Complete treatment without informing patient. | Yes(n=33) 28%No(n=85) 72% | Yes(n=18) 15%No(n=100) 85% | 54.709** |

| Didn’t inform patient and not removing the separated instrument. | Yes(n=14) 12%No(n=104) 88% | Yes(n=10) 9%No(n=108) 91% | 81.164** |

| Think that instrument separation impact RCT. | Yes(n=83) 70%No(n=35) 30% | Yes(n=104) 88%No(n=14) 12% | 37.669** |

Note: (p-value <0.0001) Chi-square value shows**Results are highly significant.

Most frequent files and alloy of manufacture with SEF.

Which part and stage of root canal most commonly with SEF.

Most frequent causes of SEF.

(A) Most frequent files and alloy of manufacture with SEF. Statistically significant difference observed (P<0.0001). (B) Most frequent SEF size. Statistically significant difference observed (P<0.0001). (C) Most common part of root canal and stage of treatment affected by SEF. Statistically significant difference observed (P<0.0001). (D) Causes of SEF. Statistically significant difference observed (P<0.0001).

Root canal morphology as a cause of SEF.

Most common teeth with SEF.

Root canals with SEF. Management options for SEF

(A) Root canal anatomy and morphology as one cause of SEF. Statistically significant difference observed (p<0.0001). (B) Most frequently affected teeth with SEF. Statistically significant difference observed (p<0.0001). (C) Root canals with SEF. Statistically significant difference observed (p<0.0001). (D) Management options of SEF. Statistically significant difference observed (p<0.0001).

Part II: Analysing results of 17 questions for dentists only. Using chi-square test found that all results are highly significant (p<0.0001)

Treatment options:

– Out of total number of dentist 44% could successfully bypass the SEF in coronal third of root canal, while 30% in middle, and 26% in apical third the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001).

– Small size SEF significantly can bypass by 81% of dentists, meanwhile 85% dentist successfully bypassed using small size files (p<0.001) [Table/Fig-11].

– Mishaps may resulted while attempting to bypass SEF from root canal, 56% of dentists significantly resulted in ledges, 25% perforations, 12% over enlargement of root canal space, and finally 5% resulted in apical transportation. (p<0.0001) [Table/Fig-12].

– Regarding removal of SEF from canal 81% of dentists tried to remove it, 53% of them successfully removed significantly from coronal third followed by 42% from middle finally 5% from apical third (p<0.0001).

– Concerning removal methods, 42% of dentists significantly removed SEF using ultrasonic device under visualization of operating microscope, while 23% used conventional methods, (17%) need special devices (p<0.0001)

Follow up and prognosis:

– Statistically significant number of dentist 93% will follow up the cases after leaving SEF in root canal, in addition 73% of cases showed that prognosis is a multifactorial issue (p<0.0001).

– About the effect of instrument position within the root canal on prognosis, statistically significant 55% of poor prognosis cases showed that SEF in the middle third, 28% in apical third, while 17% were in coronal third.

– As regards effect of timing of instrument separation; statistically significant 54% of poor prognosis cases happened during canal negotiation stage, while 42% were during cleaning and shaping stage and finally 4% at the end of cleaning and shaping procedures (p<0.0001).

– A high statistically significant 82% of poor prognosis cases were with non-vital pulp tissue. Meanwhile concerning the influence of previous state of the periapical tissue, statistically significant 70% showed poor prognosis with periapical abscess, 19% of cases with loss of lamina dura continuity, while 6% with periodontitis and finally 5% of cases were within normal before treatment start (p<0.001) [Table/Fig-13].

Management options for SEF. (n=118)

| Question | Choices | Results | p-value |

|---|

| Canal third successfully bypass SEF | CoronalMiddleApical | 44%**30%**26%** | p<0.0001 |

| File Size which easily bypassed SEF | SmallLarge | 81%**19%** | p<0.0001 |

| Size of files used for bypassing SEF | SmallLarge | 85%**15%** | p<0.0001 |

| Which procedure error results while bypassing | - Over enlargement - Ledge formation- Apical transportation- Perforation | 12%**56%**5%**25%** | p<0.0001 |

| Canal third successfully remove SEF | CoronalMiddleApical | 53%**42%**5%** | p<0.0001 |

| Methods used to remove SEF | Masseran kitUltrasonicsConventional methodsSpecial device | 13%**42%**23%**4%** | p<0.0001 |

Note: (p-value <0.0001) Chi-square value shows**Results are highly significant.

SEF management mishaps (n=118)

| Errors | During bypassing (n=118) | During removal (n=118) |

|---|

| Over enlargement of canal | n=14 12% ** | n=30 25%** |

| Ledge formation | n=66 56%** | n=50 42% ** |

| Canal irregularities | n=2 2% ** | n=5 4% ** |

| Apical transportation | n=6 5% ** | n=5 4% ** |

| perforation | n=30 25% ** | n=28 25%** |

| Repair error and complete procedure | n=61 52%** | n=64 54%** |

| Repair error and stop procedure | n=57 48% ** | n=54 46%** |

Note: (p-value <0.0001) Chi-square value shows**Results are highly significant

Follow up and prognosis. (n=118).

| Question | Choices | Results | p value |

|---|

| Follow up of SEF | - Yes- No | 93%**7% ** | <0.0001 |

| Canal part with SEF | - Coronal- Middle- Apical | 17%**55%**28% ** | <0.0001 |

| Stage of Root canal treatment | - Canal negotiation- Cleaning and shaping- After Cleaning and shaping | 54%**42%**4%** | <0.0001 |

| Pulp status | - Vital- Non – vital | 18%**82%** | <0.0001 |

| Periapical status | - Normal- Periodontitis- Periapical abcess- Loss of lamina dura | 5%**6%**70%**19%** | <0.0001 |

Note: (p-value <0.0001) Chi-square value shows**Results are highly significant

Discussion

This is a cross-sectional and retrospective clinical study aimed to compare the incidence, factors contributing to separate endodontic files between dentists and undergraduates and analysing results of treatment options, management mishaps and prognosis of separated endodontic files during endodontic treatment among dentists in Riyadh area. The response rate among dentists was 79% and 90.7% among students. Every question had a different number of total respondents, suggesting that participants chose freely which questions they felt comfortable answering.

A 57.6% of dentists and 7.6% of dental students broke files during RCT. Gandevivala et al., reported that the prevalence of broken instruments during RCT ranges from 0.5% to 5% [2]. An 87% of dentists and 98% of students informed their patients about file separation that corresponds with Choksi et al., reported that the patient should be informed about SEF when breakage occurs clinically during root canal treatment (p<0.001) [20]. A 59% of dentists and 58% of students informed patients and completed treatment in another appointment while (41%) of dentists and (42%) of students. Informed patients and completed treatment in the same visit that corresponds with Simon et al., that reported if the location of SEF and canal contamination precludes easy removal or bypass, then treatment should be completed in the same visit, or it will be postponed to another appointment [11]. A 70% of dentists and 88% of students agree and thought that file separation impact and hinder proper preparation of root canal space corresponds with those of Choksi et al., and Vivekananda et al., [20,21].

The higher percentage of separation cases with dentists and students were of stainless steel files followed by Ni-Ti files and hand files followed by rotary files that against Mukhtar et al. , that reported that- the incidence of separated instruments has increased with the increased use of nickel-titanium (Ni-Ti) instruments hand or rotary [22] while Simon et al. , reported that Ni-Ti instruments are not more fragile than a stainless steel instrument of equivalent size [11]. Fractured instruments occurred long before the introduction of rotary Ni-Ti instruments. Small size files are more separated (81%) that corresponds with Choksi et al. , reported that small endodontic instruments (size 15, 20) are more prone to distortion as a result of stressing on their small cross sections [20]. Gencoglu and Helvacioglu reported that rotary instruments size #25.04 were the most fractured rotary instruments at a length of 2.5 mm because they are the most common MAF size [23]. (73%) of SEF were in apical third of root canal, (78%) of SEF during cleaning and shaping of root canal, (45%) of causes of SEF were root canal anatomy and (66%) occurred in curved canals (p<0.001) corresponds with Madarati et al., reported that the risk of SEF in the apical third of the canal is higher when compared to coronal and middle thirds that is because of most curved canals are narrow and the contact surface with the dentinal walls increases with curvature increase so that files undergo greater fatigue that lead to separation [24]. Choksi et al., reported that Curved and narrow canals have a higher risk of instrument fracture than straight and wide canals [20].

A 94% of SEF more separated in molars, 66% of SEF in Mesiobuccal canal followed by 24% Mesiolingual canal corresponding with Madarati et al., reported a higher prevalence of SEF has been reported in molars particularly in the mesial roots of mandibular molars [24].

Dentists and students faced SEF either referred cases to specialists (36%), successfully bypassed 31%, 27% successfully removed or 6% left inside root canal with true blockage. That corresponds with Gandevivala et al., reported that when an instrument fractures during root canal preparation [2], there are three basic management options: (i) Remove it; (ii) Bypass and seal it within the root canal; or (iii) block the root canal with it (p<0.0001).

A 44% of dentists bypassed SEF and 53% could successfully remove SEF from coronal third Gencoglu and Helvacioglu reported that 100% success rate for removal and bypassing the SEF obtained in coronal third of the all canals [23]. The success rate was the lowest in the apical third. A 42% of dentists could successfully remove SEF using ultrasonics under visualization of operating microscope while 23% successfully used conventional methods (p<0.0001) corresponding with Gencoglu and Helvacioglu which confirmed that ultrasonic with the aid of an operating dental microscope is more successful in removing fractured instruments than conventional methods [23]. A 71% of dentists used EDTA as a chelating agent during bypassing or removal of SEF corresponding with Jadhav that reported that the use of EDTA facilitate SEF negotiation with files as it is used to soften the root canal wall dentin around separated instruments [25].

All dentists in this study while trying to remove or bypass the separated instrument produced ledges, perforations, over enlargement of the canal, canal irregularities and apical transportation that corresponds with Choksi et al., that reported that attempting to remove or bypass SEF can lead to ledge formation, over enlargement, canal transportation and perforation [20].

(73%) of retained SEF cases showed good prognosis that against Gandevivala et al., reported that the fractured segment always accompanied with bacteria and dentine debris which considered as a foreign object that cause inflammation and so treatment failure [2]. But corresponding with Vivekananda et al., that reported that a retained instrument had no influence on the outcome of endodontic treatment, few studies have found reduced success rate [21].

A 69% of SEF cases showed good prognosis when separation happened after complete cleaning and shaping, 77% were with vital pulp tissue, 88% were with normal periapical tissue before separation and 68% of SEF found in the apical third of root canal (p<0.001). A 70% of poor prognosis cases were with periapical abcess before separation, 54% of SEF happened during canal negotiation stage that prevented complete cleaning and shaping, 55% of SEF were in the middle third of root canal beyond canal curvature or at its level, 82% of cases were with non-vital pulp tissue corresponding with Vivekananda et al. , that reported that the main prognostic factor in SEF cases is the presence or absence of a pre-operative periradicular pathosis [21].

Successful prognosis is affected by the evaluation of the pulp status, the root canal infection, the root canal anatomy, the position and type of fractured instrument and the amount of damage that would be caused to the remaining tooth structure. Chauhan et al., reported that a retained fractured instrument inside the root canal without complete obturation and coronal seal allows micro-organisms to penetrate inside the canal developing periapical lesion and so treatment failure [26].

Conclusion

Incidence of separated endodontic files (SEF) among dentists was higher than students this is due to the more cases they treat than students. The higher percent of students referred SEF cases while dentists tried to remove or bypass the SEF.

The higher percent of SEF were hand stainless steel more than Ni-Ti rotary files and of small size files. SEF more separated in apical third during root canal preparation due to root canal anatomy more of curved canals in molar teeth especially in mesiobuccal and mesiolingaul canals.

Dentists faced this problem reported that the most successful method for SEF removal was ultrasonics under visualization of operating microscope. They also successfully bypassed small size SEF using another small size files or left SEF inside the root canal and followed the cases but this depended on the pulp status, periapical tissue and lamina dura state before separation of the endodontic files. While trying to remove or bypass SEF dentists reported that the higher percentages of errors were ledges then perforations, over enlargement of root canal and apical transportation.

Dentists reported that the good prognosis cases were of vital pulp tissue, normal periapical tissue and lamina dura before separation problem occurs and all of poor prognosis cases were in contrary with these situations.

Note: (p-value <0.0001) Chi-square value shows**Results are highly significant.

Note: (p-value <0.0001) Chi-square value shows**Results are highly significant.

Note: (p-value <0.0001) Chi-square value shows**Results are highly significant

Note: (p-value <0.0001) Chi-square value shows**Results are highly significant

[1]. Rahimi M, Parashos P, A novel technique for the removal of fractured instruments in the apical third of curved root canalsInt Endod J 2009 42:264-70. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Gandevivala A, Parekh B, Poplai G, Sayed A, Surgical Removal of Fractured Endodontic Instrument in the Periapex of Mandibular First MolarJ Int Oral Health 2014 6:85-88. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Cujé J, Bargholz C, Hülsmann M, The outcome of retained instrument removal in a specialist practiceInt Endod J 2010 43:545-54. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Al-Qudah AA, Awawdeh LA, Root canal morphology of mandibular incisors in a Jordanian populationInt Endod J 2006 39:873-77. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Vaudt J, Bitter K, Neumann K, Kielbassa AM, Ex vivo study on root canal instrumentation of two rotary nickel-titanium systems in comparison to stainless steel hand instrumentsInt Endod J 2009 42:22-33. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Bonaccorso A, Cantatore G, Condorelli GG, Schäfer E, Tripi TR, Shaping ability of four nickel-titanium rotary instruments in simulated S-shaped canalsJ Endod 2009 35:883-86. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Carvalho LA, Bonetti I, Borges MA, A comparison of molar root canal preparation using stainless-steel and Nickel-Titanium instrumentsJ Endod 1999 25:807-10. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Sattapan B, Nervo GT, Palamara JE, Messer HH, Defects in rotary nickel-titanium files after clinical useJ Endod 2000 26:161-65. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Hülsmann M, Schinkel I, Influence of several factors on the success or failure of removal of fractured instruments from the root canalEndod Dent Traumatol 1999 15:252-58. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Grossman LI, Guidelines for the prevention of fracture of root canal instrumentsOral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1969 28:746-52. [Google Scholar]

[11]. Simon S, Machtou P, Tomson P, Adams N, Lumley P, Influence of fractured instruments on the success rate of endodontic treatmentDent Update 2008 35:172-79. [Google Scholar]

[12]. Gencoglu N, Helvacioglu D, Comparison of the different techniques to remove fractured endodontic instruments from root canal systemsEur J Dent 2009 3:90-95. [Google Scholar]

[13]. Parashos P, Messer HH, Rotary NiTi instrument fracture and its consequencesJ Endod 2006 32:1031-43. [Google Scholar]

[14]. Plotino G, Pameijer CH, Grande NM, Somma F, Ultrasonics in endodontics: A review of the literatureJ Endod 2007 33:81-95. [Google Scholar]

[15]. Ruddle CJ, Broken instrument removal. The endodontic challengeDent Today 2002 21:70-72.:4 [Google Scholar]

[16]. Suter B, Lussi A, Sequeira P, Probability of removing fractured instruments from root canalsJ Endod 2005 38:112-23. [Google Scholar]

[17]. Terauchi Y, O’Leary L, Kikuchi I, Asanagi M, Yoshioka T, Kobayashi C, Evaluation of the efficiency of a new fileremoval system in comparison with two conventional systemsJ Endod 2007 33:585-88. [Google Scholar]

[18]. Öztan MD, Endodontic treatment of teeth associated with a large periapical lesionInt Endod J 2002 35:73-78. [Google Scholar]

[19]. Soares JA, Brito-Junior M, Silveira FF, Nunes E, Santos SM, Favourable response of an extensive periapical lesion to root canal treatmentJ Oral Sci 2008 50:107-11. [Google Scholar]

[20]. Choksi D, Idnani B, Kalaria D, Patel RN, Management of an Intracanal Separated Instrument: A Case ReportIran Endod J 2013 8:205-07. [Google Scholar]

[21]. Vivekananda Pai AR, Mir S, Jain R, Retrieval of a metallic. obstruction from the root canal of a premolar using Masserann techniqueContemp Clin Dent 2013 4:543-46. [Google Scholar]

[22]. Andrabi SM, Kumar A, Iftekhar H, Alam S, Retrieval of a separated nickel-titanium instrument using a modified 18-guage needle and cyanoacrylate glue: a case reportRestor Dent Endod 2013 38:93-97. [Google Scholar]

[23]. Gencoglu N, Helvacioglu D, Comparison of the Different Techniques to Remove Fractured Endodontic Instruments from Root Canal SystemsEur J Dent 2009 3:90-95. [Google Scholar]

[24]. Madarati AA, Watts DC, Qualtrough AJE, Factors contributing to the separation of endodontic filesBr Dent J 2008 204:241-45. [Google Scholar]

[25]. Jadhav GR, Endodontic management of a two rooted, three canaled mandibular canine with a fractured instrumentJ Conserv Dent 2014 17:192-95. [Google Scholar]

[26]. Chauhan R, Chandra A, Singh S, Retrieval of a separated instrument from the root canal followed by non-surgical healing of a large periapical lesion in maxillary incisors - A case reportEndodontology 2013 25:68-73. [Google Scholar]