Is Video Podcast Supplementation as a Learning Aid Beneficial to Dental Students?

Shivananda Kalludi1, Dhiren Punja2, Raghavendra Rao3, Murali Dhar4

1 Associate Professor, Department of Physiology, Akash Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Devanahalli, Bengaluru, India.

2 Assistant Professor, Department of Physiology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal University, Manipal, India.

3 Professor, Department of Physiology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal University, Manipal, India.

4 Associate Professor, Department of Population Policies and Programmes, International Institute for Population Sciences, Mumbai, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Dhiren Punja, Assistant Professor, Department of Physiology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal University, Manipal-576104, India. E-mail : dhirenpunja82@hotmail.com

Introduction

Podcasting has recently emerged as an important information technology tool for health professionals. Podcasts can be viewed online or downloaded to a user computer or a handheld multimedia device like a portable MP3 player, smart phone and tablet device. The principal advantage of the podcast is that the presentation of information need not be linked with any particular time or location. Since students are familiar with newer technology tools and may be using it on a regular basis, video podcast could serve as a convenient tool for students to help remember both conceptual and factual information.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to assess the attitude of first year dental students towards video podcast supplementation and to assess the efficacy of video podcast as a teaching aid in comparison to text book reading.

Materials and Methods

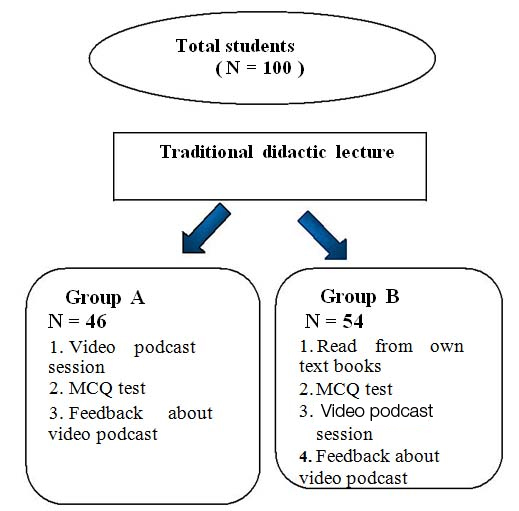

First year dental students were recruited for this study. A didactic lecture class was conducted for the students (n=100). The students were then randomly divided into two groups. Students present in group A (n=46) underwent a video podcast session followed by a multiple choice question test. This was followed by student feedback to assess the usefulness of video podcast. Students belonging to group B (n=54) had a study session for 20 minutes followed by the MCQ test. Students then underwent the video podcast session followed by feedback to assess the utility of video podcast. Mann-Whitney U test was applied to compare the difference in the median MCQ score between the two groups.

Results

The findings revealed a significant gain in the median MCQ score in the intervention group (group A) when compared to control group (Group B). In the feedback form, 89% of students agreed that the video podcast might be useful as it would enable them to view slides and hear the lectures repeatedly.

Conclusion

Students who underwent the video podcast session performed significantly better in the MCQ test compared to students who underwent text book reading alone. This demonstrates an advantage of video podcasts over text book reading. Majority of students accepted the benefits of video podcast supplementation.

Audio podcast, Fleming’s VARK, Technology tool

Introduction

Podcasting has recently emerged as an important information technology learning tool for health professionals and consumers around the world [1]. Technology has evolved over the past decade and the younger generation is growing up using information technology and its information collecting devices [2]. With the presence of more digitally engaged students, medical and dental institutes are incorporating newer technologies to disseminate information. Educational information for students need not solely be delivered through live lectures or obtained from textbooks. Web based applications like wikis, blogs, podcasts have been increasingly adopted by many health professionals and educational services. Because of their ease of use and rapidity of deployment, they offer the opportunity for powerful information sharing [3]. In podcasting, information is recorded digitally using audio or video recording software. The recorded MP3 or MP4 file is then uploaded to a website or published through programs like iTunes [4]. The file can be played on a computer, digital player or smart phone. Sandars et al., have suggested that all educators need to promote computer-based technology in the undergraduate curriculum [5].

Although many web-based resources are available in the form of websites and CD-ROMs, not all have the advantage of being pocket-portable or instantly accessible [6]. One of the advantages of podcast is its ability to view from multiple viewing platforms [7]. Podcasts can be viewed online or downloaded to a user’s computer or handheld multimedia device like portable MP3 player, smart phone or, tablet device [8]. In addition, with podcasts students have an opportunity to revisit material as many times as required. Studies have found this to be advantageous to students who have learnt English as a second language [5].

Previously, podcasts only allowed the distribution of audio files and hence they were advantageous to be used for topics that did not require images. However, new technology allows one to publish, disseminate and download video files as a video podcast. Video podcasts or VOD casts (Video on Demand Podcasts) are syndication feeds that are in movie file format (MPEG-4 {Moving Picture Experts Group, Audio Player 4}) instead of MP3 format (audio only). These digital presentations are not limited to videos, but can be used for slide shows or animation [7]. Video podcasts could be in the format of lectures, skill based (helping students learn specific procedural tasks) or supplementary support material [9]. A personal computer with a high-end CPU, extensive memory and large-capacity storage space enables users to produce and encode videos with relative ease [10].

A video format offers an expressive non-textual way to capture and present information. A major assumption of the cognitive learning model is that a learner’s attention is limited and therefore selective. With more interactive and richer media available, a learner who prefers an interactive learning style has more flexibility to meet individual needs [11]. Providing video podcasts will enable students to engage with concepts during lecture rather than note taking and allows students to assimilate complex information at their own pace [12]. Jones et al., observed that students found video podcasts were beneficial in learning [13]. Video streaming has benefited students with respect to reviewing previously attended lectures [10]. Parson et al., observed that audio podcasts and video podcasts were beneficial when used in conjunction with lecturers’ slides [14]. Pierce et al., observed that students preferred flipped classroom model containing video podcasts [15]. Smith et al., observed that video-clips from a digital camera were the preferred method for demonstrating tooth preparations in a preclinical dentistry course [16].

Contrary to the above mentioned studies, Solomon et al., observed that no differences existed in performance among students who underwent digital lectures when compared to those who underwent live lectures [17]. However, in the above mentioned study students belonged to different courses.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the efficacy of video podcasts when used as a supplement to live lectures. Another purpose was to assess the students’ perception of video podcast with regard to its usefulness as a supplementary learning aid.

Materials and Methods

Preparation of podcasts and validation of questionnaire

Script related to the subject and power-point slides were prepared by two faculties of the Physiology department. Video podcast was prepared in a quiet room to prevent background noise. The Camtasia software was downloaded from the internet (www.techsmith.com) and was employed to prepare the podcast. The digital files were saved in MP4 format. The total duration of the video podcast was 12 minutes. Eight statements intended to assess the attitude of students towards video podcast were e-mailed to five faculty members of physiology department to validate the questions. Faculties suggested modifications in three statements which were incorporated in the final questionnaire. Likert-type statements were scored, from 1(strongly agree), 2 (agree), 3 (can’t say), 4 (disagree) to 5 (strongly disagree) for negative statements (numbered 3, 4, 6 and 7) and for positive statements (numbered 1, 2, 5 and 8), from 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (can’t say), 4 (agree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Inclusion criteria of subjects

All (n=100) students enrolled in the first year dental course curriculum agreed to participate in the study. Students were informed that their participation would be voluntary.

Study design

This cross-sectional study was conducted in December 2013 after obtaining ethical clearance from the Institutional Ethics Committee (653/2013). Students were informed about the study 10 days in advance and the purpose of the study was explained to them. The study was conducted in the lecture halls of the Dental College. Written informed consent was obtained from them. All students attended a 20 minute live lecture in a single classroom. The topics taught were structure of gastric gland, mechanism of hydrochloric acid production, phases of gastric acid secretion, function of gastric mucosal barrier, role of antacids and pathophysiology of gastric ulcers. An overview of study design has been shown in [Table/Fig-1]. The students were then randomly divided into two groups. Students with even serial numbers formed group A and students with odd serial numbers formed group B.

Group A students underwent the video podcast session for 12 minutes in a separate class room. The video podcast was a structured podcast and contained only the highlights and concepts of the topics that were covered in the live lecture. The podcast was not uploaded to the internet to prevent propagation to students in the control group (group B). Group A then underwent an MCQ test consisting of ten questions based on the topics covered in live lecture. The same group of students then completed a Likert-type questionnaire consisting of eight statements. These statements were used to assess the students’ attitude towards the video podcast. [Table/Fig-2] gives the questionnaire.

Mean attitude score of both the groups for each statement in the questionnaire

| Statements | Mean attitudescore± S.D |

|---|

| 1. Viewing video podcast after the live lecture class enabled me to understand the topic better | 3.30± 1.01 |

| 2. I believe that including video podcast as a teaching aid along with didactic lectures will enhance my performance in my exams | 4.16± 0.82 |

| 3. I might not use video podcasts because they are time consuming | 3.97± 0.91 |

| 4. I might not use video podcast because it requires a computer/laptop for viewing which might not be readily available at all times | 3.99± 1.O1 |

| 5. I find video podcast useful because it will enable me to view slides and hear the lectures repeatedly which might help me for my exams | 4.33± 0.77 |

| 6. Viewing video podcasts are not a good form of learning | 4.27± 0.81 |

| 7. Video podcasts are not a convenient form of learning as I might face some technical difficulties in using them | 4.10± 1.08 |

| 8. Supplementing video podcasts with didactic lectures is necessary to understand difficult topics in Physiology | 4.00 ± 0.92 |

| Overall Mean score | 32.12 ± 4.64 |

Group B students were considered as the control group. After the live lecture they were given 12 minutes to review the topics covered in the live lecture class from their own textbooks in a separate class room. The same group then underwent a MCQ test for assessment, after which they had video podcasting session. The questionnaire was distributed among the students and then they completed the questionnaire consisting of eight statements.

Statistical Analysis

Data was compiled using Microsoft Excel and analyzed using SPSS version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). In order to test the normalcy of MCQ scores in two groups, Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied. Since the MCQ scores in Group A were found to deviate from normalcy (p<0.031), Mann-Whitney U test was applied to compare the significance of difference in the median MCQ scores between the two groups.

Results

The average age of the students belonging to group A was 18.34 years and group B was 18.46 years. The total score for the MCQ test was 10 and each correct response was awarded 1 mark and no score was given for an incorrect response. Students belonging to group A obtained a median MCQ score of 6.0. The median MCQ score of group B was 5.0. Significant difference in the median MCQ scores was observed between the two groups [Table/Fig-3].

Median and Interquartile range(IQR) of MCQ scores.

| Score | Group A (videopodcast) | Group B | p-value |

|---|

| Median(IQR) | 6.0 (2) | 5.0 (3) | 0.021 |

Since p-value is less than 0.05, scores of group A students are significantly better than group B students

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to explore utility of video podcasts with respect to understanding the subject content and impact on students’ performance in the examination. We found that students who were supplemented with video podcast performed significantly better in the MCQ test than students who were not supplemented with video podcasts.

Conflicting reports have been published so far regarding the usefulness of video podcasts. A few institutions have observed that mere audio-format lectures were in demand by students and other centers found that visual educational content were necessary [18,19].

Hill et al., observed that no significant differences in the examination of essay grades prior to and post adoption of podcasts. However in the same study investigators found that video podcasts were perceived as useful resource for revision and assessment with students agreeing that vodcasts provided visual images which stimulated factual recall and highlighted knowledge gaps [20]. Another study has shown that video podcast offered no additional benefit to the students [21].

Contrary to the findings observed in the present study, Kazlaukas et al., observed that students prefer to learn in face-to-face environments and reading in set study environments when compared to podcasts. However students included in the above mentioned study were from nursing and business programme [22].

It has been suggested that medical skills are effectively taught through multisensory approaches based on Fleming’s VARK (Visual, Auditory, Read/Write, Kinesthetic) model, which proposes that some learners have a preferential sensory channel through which they best receive and integrate information, while audio podcasts may mainly benefit the auditory learners, video podcasts may benefit both the visual and auditory learners as well as bimodal (visual/auditory) learners [23]. Kalludi et al., observed that 63 percentage of students felt absence of images and diagrams in audio podcasts was a disadvantage [4]. In the present study 89% of students agreed that viewing slides and hearing the information simultaneously might help them [Table/Fig-4,5].

Median and quartile attitude score for each statement in the questionnaire as mentioned in [Table/Fig-2] among students in both groups

| Statement number | Group A | Group B |

|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) |

|---|

| 1. | 3.0 (1) | 3.0 (1) |

| 2. | 4.0 (1) | 4.0 (1) |

| 3. | 4.0 (2) | 4.0 (2) |

| 4. | 4.0 (1) | 4.0 (2) |

| 5. | 4.5 (1) | 4.0 (1) |

| 6. | 4.5 (1) | 4.0 (1) |

| 7. | 4.5 (1) | 4.5 (2) |

| 8. | 4.0 (1) | 4.0 (2) |

Number of students in both the groups who responded to each statement in the questionnaire as mentioned in [Table/Fig-2] with agree, disagree or can’t say respectively

| Sl. Number ofstatements in thequestionnaire | Number of students(percentage) whoAgree/Stronglyagree | Number of students(percentage) whoDisagree/ Stronglydisagree | Number of students(percentage) whoCan’t say |

|---|

| 1. | 39(42.4) | 12(13.0) | 41(44.6) |

| 2. | 77(83.7) | 2(2.2) | 13(14.1) |

| 3. | 63(68.5) | 4(4.4) | 25(27.2) |

| 4. | 65(70.6) | 10(10.9) | 17(18.5) |

| 5. | 82(89.1) | 2(2.2) | 8(8.7) |

| 6. | 77(83.7) | 3(3.3) | 12(13.0) |

| 7. | 65(70.7) | 8(8.7) | 19(20.7) |

| 8. | 70(76.1) | 7(7.6) | 15(16.3) |

Meade et al., observed that edited audio podcasts as a supplementary tool were found to enhance understanding of pharmacology [24]. The same study observed consistent improvement in the mean exam score of students. However, in the above mentioned study students were from pharmacy, paediatric nursing, adult nursing, mental health nursing and community matron. This probably shows that audio podcasts are beneficial to students with diverse educational qualifications.

Meade et al., observed that 65% of students found podcast was "very helpful" in promoting understanding of pharmacology and another study observed 35% of students "strongly agreed" that biology podcasts are helpful in understanding the subject [24,25]. In the present study 42% of students agreed (“strongly agree” and “agree”) that video podcast helps them to understand the subject indicating podcast serves as an important purpose in education.

In the present study a majority of students agreed that viewing video podcast after live lecture class enabled them to understand the topic better. Eighty nine percentage of the students felt that video podcast will help them enhance their performance in the examinations. Copley et al., observed that the use of video podcasts was rated superior in comparison to traditional printed handouts and lecture notes [12].

In the present study some students felt that video podcast might have a disadvantage since a computer or a laptop may be required to view video podcast which may not be always feasible. A small percentage of the students felt that viewing video podcasts may be too time consuming or that they might face technical difficulties in using them. Copley et al., have stated that disadvantage of video podcast is that not all portable media players have video capability and only 14% of the individuals had portable devices which also had video capability. In the same study some students felt downloading video podcast was time consuming especially when the internet connectivity was not optimal [12].

Narula et al., have used five minute medicine videos for clinical clerks. Majority of clinical clerks agreed that the medicine video podcasts were effective learning tools appropriate for clinical clerks and time-efficient, more so than conventionally used resources like textbooks and online resources [19].

Even with video podcasts being available, classroom interaction is necessary as it gives opportunity to the students to ask doubts and clarify concepts. Copley et al., observed that students will not skip classes if video podcasts are available to them, as lecture classes offers an opportunity for interaction and provides a structured learning environment [12].

Conclusion

Insights achieved from this study shows that students’ are benefited from video podcast and acceptability of video podcast is good among first-year dental students. With many universities now providing online resources for students, video podcasts have the potential to be widely used to enhance the students learning experience. Although didactic lecture still has an indispensable role in medical education and is probably the most employed teaching technique, alternative strategies like video podcasts can greatly facilitate the students learning experience and provide a more reliable source of knowledge among the vast array of information that is now available online for students. Additional research on video podcast in other subjects may help to further establish the benefits of using video podcasts as a supplement to live lectures.

Since p-value is less than 0.05, scores of group A students are significantly better than group B students

[1]. Johnson L, Grayden S, Podcasts—an emerging form of digital publishingInt J Comput Dent 2006 9(3):205-18. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Peroz I, Beuche A, Peroz N, Randomized controlled trial comparing lecture versus self studying by an online toolMedical Teacher 2009 31:508-12. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Boulos MN, Maramba I, Wheeler S, Wikis, blogs and podcasts: a new generation of Web-based tools for virtual collaborative clinical practice and educationBMC Med Educ 2006 6:41 [Google Scholar]

[4]. Kalludi SN, Punja D, Pai KM, Dhar M, Efficacy and perceived utility of podcasts as a supplementary teaching aid among first-year dental studentsAustralas Med J 2013 6(9):450-57. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Sandars J, Morrison C, What is the Net generation? The challenge for future medical educationMed Teach 2007 29(2):85-88. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Rainsbury JW, McDonnell SM, Podcasts: an educational revolution in the making?Journal of Royal Society of Medicine 2006 99:481-82. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Corl FM, Johnson PT, Rowell MR, Fishman EK, Internet-based dissemination of educational video presentations: a primer in video podcastingAJR Am J Roentgenol 2008 191(1):23-27. [Google Scholar]

[8]. White JS, Sharma N, Boora P, Surgery 101: evaluating the use of podcasting in a general surgery clerkshipMed Teach 2011 33(11):941-43. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Kay R, Using video podcasts to enhance technology-based learning in preservice teacher education: A formative analysisJournal of Information Technology and Application in Education 2012 1(3):97-104. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Bennett PN, Glover P, Videostreaming: implementation and evaluation in an undergraduate nursing programNurse Educ Today 2008 28(2):253-58. [Google Scholar]

[11]. Zhang D, Zhou L, Briggs RO, Nunamaker JF, Instructional video in e-learning: assessing the impact of interactive video on learning effectivenessInformation & Management 2006 43(1):15-27. [Google Scholar]

[12]. Copley J, Audio and video podcasts of lectures for campus-based students: production and evaluation of student useInnovations in Education and Teaching international 2007 44(4):387-99. [Google Scholar]

[13]. Jones K, Doleman B, Lund J, Dialogue vodcasts: a qualitative assessmentMed Educ 2013 47(11):1130-41. [Google Scholar]

[14]. Parson V, Reddy P, Wood J, Senior C, Educating an iPod generation: undergraduate attitudes, experiences and understanding of vodcast and podcast useLearning, Media and technology 2009 34(3):215-28. [Google Scholar]

[15]. Pierce R, Fox J, Vodcasts and active-learning exercises in a “flipped classroom” model of a Renal Pharmacotherapy moduleAm J Pharm Educ 2012 76(10):196-99. [Google Scholar]

[16]. Smith W, Rafeek R, Marchan S, Paryag A, The use of video-clips as a teaching aideEuropean Dent Educ 2012 16:91-96. [Google Scholar]

[17]. Solomon DJ, Ferenchick GS, Laird-Fick HS, Kavanaugh K, A randomized trial comparing digital and live lecture formats (ISRCTN 40455708)BMC Med Educ 2004 29(4):27-32. [Google Scholar]

[18]. Robert B, Trelease Diffusion of innovations: Anatomical informatics and iPodsAnat Rec B New Anat 2006 289(5):160-68. [Google Scholar]

[19]. Narula N, Ahmed L, Rudkowski J, An evaluation of the 5 minute medicine video podcast series compared to conventional medical resources for the internal medicine clerkshipMed Teach 2012 34(11):e751-55. [Google Scholar]

[20]. Hill JL, Nelson A, New technology, new pedagogy? Employing video podcasts in learning and teaching about exotic ecosystemsEnvironmental Education Research 2011 17(3):393-408. [Google Scholar]

[21]. Dupagne M, Millette DM, Grinfeder K, Effectiveness of video podcast use as a revision toolJournalism and Mass communication educator 2009 64(1):54-70. [Google Scholar]

[22]. Kazlauskas A, Robinson K, Podcasts are not for everyoneBritish Journal of Educational Technology 2012 43(2):321-30. [Google Scholar]

[23]. Fleming ND, Mills C, Not another inventory, rather a catalyst for reflectionTo Improve Academy 1992 42:137-49. [Google Scholar]

[24]. Meade O, Bowskill D, Lymn JS, Pharmacology as a foreign language: a preliminary evaluation of podcasting as a supplementary learning tool for non-medical prescribing studentsBMC Med Educ 2009 9:74-85. [Google Scholar]

[25]. Mostyn A, Jenkinson CM, McCormick D, Meade O, Lymn JS, An exploration of student experiences of using biology podcasts in nursing trainingBMC Med Educ 2013 13:12-19. [Google Scholar]