Primary Cavernous Haemangioma of the Frontal Bone: Computed Tomography Features

Mainak Dutta1, Arijit Jotdar2, Sohag Kundu3, Subrata Mukhopadhyay4

1 RMO-Cum-Clinical Tutor, Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head-Neck Surgery, Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, India.

2 Junior Resident, Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head-Neck Surgery, Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, India.

3 RMO-Cum-Clinical Tutor, Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head-Neck Surgery, Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, India.

4 Professor, Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head-Neck Surgery, Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Mainak Dutta, RMO-Cum-Clinical Tutor, Department of Otorhinolaryngology and Head-Neck Surgery, Medical College and Hospital, 88, College Street, Kolkata-700073, West Bengal, India. E-mail : duttamainak@yahoo.com

Calvarial, Proptosis, Rare lesions

Primary cavernous haemangiomas of the calvarium are rare lesions and constitute about 0.2% of the benign skull neoplasms [1]. They are slow-growing, and are usually detected earlier as there are chances of developing facial deformity – therefore they seldom attain large size, and are amenable to surgical excision. Nevertheless, a cavernous haemangioma of skull-bone is not a usual suspicion in a patient presenting with bony facial swelling, given the fact that computed tomography (CT) findings are only occasionally suggestive [1,2]. Consequently, they are mostly detected at surgery and confirmed on subsequent histopathology [2–4].

We encountered a 40-year-old Indian housewife with a progressive painless swelling over the left side of her forehead for two years, and bulging of her left eye for seven months. She noticed gradual dimness of vision in her left eye, associated with double vision. The swelling [Table/Fig-1a&b] was large and globular, over the left frontal region, and was bony hard. It was smooth, non-tender, non-pulsatile, with free overlying skin, and without any sign of inflammation. She had left-sided proptosis with down and outward displacement of the eyeball. The affected eye had restricted movements with a visual acuity of 6/12. There was no other visible swelling in the rest of her body, and she had no history of trauma over her forehead. Neurological and other systemic examinations were unremarkable.

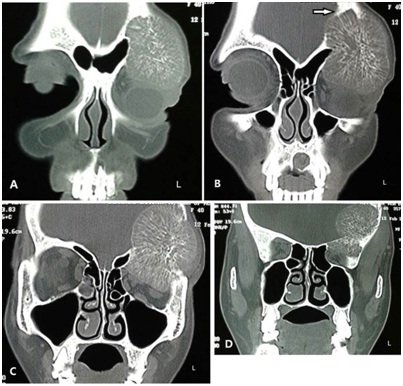

Our initial suspicion based on the clinical appearance of the swelling was that of a fibro-osseous lesion. Subsequent CT of the skull and orbits [Table/Fig-2a-d] revealed a well-demarcated, contrast-enhancing, expansile osteolytic lesion arising from the frontal bone. It was about six cm in greatest dimension, and involved both the outer and inner tables. The lesion had a thin sclerotic rim, especially prominent where it abutted against the dura pushing it medially towards the frontal lobe but without causing midline shift. It showed multiple trabeculae arranged radially, moving centrifugally from a sclerotic osseous core, forming a “sun-burst” or “sun-ray” appearance. The left orbital roof was breached and the lesion encroached the orbital compartment resulting in proptosis. The CT features were highly suggestive of a haemangioma [3,4], and we had to revise our provisional diagnosis.

Cavernous haemangiomas of the calvarium are notoriously misdiagnosed due to their rarity, and most importantly because there is seldom any clue available from imaging that could lead to the correct diagnosis. Although CT is the imaging modality of choice for calvarial neoplasms, the tell-tale features characterizing a haemangioma, as we have seen in our patient, are mostly absent [2,3]. Thus a bony hard facial swelling in a young or middle-aged woman is often misrepresented clinico-radiologically as fibrous dysplasia [3], with consideration of other important differentials like osteoma, ossifying fibroma, osteomyelitis, mucocele, histiocytosis, metastasis and multiple myeloma. Careful review of the imaging however would rule out most of them, as their appearance range from intensely radiodense (osteoma), well-circumscribed lesion with osteolysis and sclerotic banding (ossifying fibroma), to homogeneous radiolucency with peripheral sclerotic rim (mucocele). Characteristic imaging features of skull haemangioma is therefore quite distinct from the rest, which, if present, should aid considerably to the diagnosis.

From the clinical perspective, diagnosing a calvarial haemangioma becomes challenging when it presents with atypical features. In our patient, the vascular tumour was unusually large, and unlike most reported cases where haemangiomas have been found to involve only the outer table of the calvarium [1,5], the tumour here had eroded the inner table as well, replacing it over a considerable extent with its thin sclerotic rim, resulting in significant dural bowing. The tumour had presented late, and there was erosion of the orbital roof causing proptosis – findings considered rare for calvarial haemangiomas [3,5]. We were therefore fortunate to have the classic CT features for haemangioma, as this implied that the surgical planning needed to be changed.

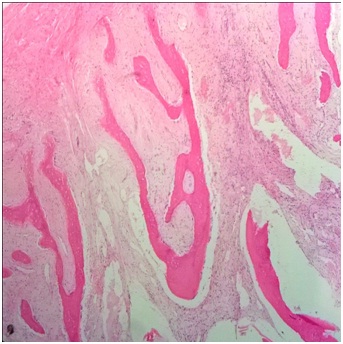

Considering the proposition that the bony trabeculae could be intimately attached with the dura and there could be practical chances of extradural and/or subdural haemorrhage while attempting to remove the tumour [5], we referred the patient to our neurosurgery colleagues for appropriate surgical management. Neurosurgical expertise was also needed for cranioplasty with split-thickness calvarial bone grafting following en-bloc removal of the tumour with 0.5-1 cm of healthy bone [1,3]. Curettage of a calvarial haemangioma rich in vascular channels and bony trabeculae (as often attempted for smaller lesions not involving the inner table/dura, or when the diagnosis is only peroperative) and subsequent radiotherapy is no longer preferred due to high chances of recurrence [3]. Feedback from the neurosurgeons and pathologists obtained later stated that the lesion in our patient was indeed a cavernous haemangioma [Table/Fig-3].

The patient presented with a large, globular, bony hard swelling on her left frontal region that resulted in proptosis; (a) frontal profile; (b) side profile. Informed consent in written has been obtained from the patient seeking permission to publish these figures

CT-scan shows a lytic lesion arising from the frontal bone that enhanced with contrast. The serial bone windows (from anterior to posterior) (a-d) show the spherical lesion to erode the external table of the calvarium (a) and progressing postero-medially to erode the inner table as well (b {arrow}). Inside the mass, the bony trabeculae radiate centrifugally from a sclerotic centre, forming the classic “sun-burst” or “sun-ray” pattern (c). The lesion has a thin sclerotic rim that is prominent at its medial convexity where it abuts against the dura causing compression over the frontal lobe but without any midline shift (c,d). The left orbital roof is breached and the lesion encroaches the orbital compartment resulting in proptosis (a,b)

Histopathology shows the cavernous vascular spaces lined by bland single-layer endothelium within the bone matrix (H&E; x 100)

Characteristic CT features are vital in diagnosing skull-bone neoplasms. For a primary calvarial cavernous haemangioma which remains mostly enclosed within the osseous plates and present as bone-hard swellings at late stages, it is crucial to have suggestive CT findings to differentiate it from other more common diagnoses related to osseous tumours/tumour-like lesions. This would help planning appropriate surgical treatment, and avoid indecision and unforeseen peroperative situations.

[1]. Murrone D, De Paulis D, Millimaggi DF, Del Maestro M, Galzio RJ, Cavernous hemangioma of the frontal bone: a case reportJ Med Case Rep 2014 8:121[doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-8-121] [Google Scholar]

[2]. Naama O, Gazzaz M, Akhaddar A, Belhachmi A, Asri A, Elmostarchid B, Cavernous hemangioma of the skull: 3 case reportsSurg Neurol 2008 70(6):654-59. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Park BH, Hwang E, Kim CH, Primary intraosseous hemangioma in the frontal boneArch Plast Surg 2013 40:283-85. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Nasser K, Hayashi N, Kurosaki K, Hasegawa S, Kurimoto M, Mohammed A, Intraosseouscavernous hemangioma of the frontal boneNeurol Med Chir 2007 47:506-08. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Politi M, Romeiki BFM, Papanagiotou P, Nabhan A, Struffert T, Feiden W, Intraosseous hemangioma of the skull with dural tail sign: radiologic features with pathologic correlationAJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2005 26:2049-52. [Google Scholar]