Alcohol use disorders are one of the most common behavioural disorders in armed forces. It is the cause of 15-20% of all psychiatric admission and many surgical and traumatic emergencies [4]. Varied alcohol consumption pattern are linked to variety of health, occupational and social problems which compromise the quality of life of Indian patients [5].

Patients with alcohol dependence syndrome are found to have frustration and disturbance in every sphere of their lives especially with regards to interpersonal relationships, jobs and family situations. This leads to greater psychological distress and lowered self esteem which in turn leads to increased alcohol consumption [6].

Social support reflects mechanisms by which interpersonal relationship empowers people to overcome adverse effects of stress. Considerable research now indicates that social support reduces or buffers the adverse psychological impact or exposure to stressful life events and ongoing life strains [7–9]. Numerous studies show the impact of perceived social support on processes related to health and disease, as well as its beneficial effect on the evolution of diseases as diverse as depression, arthritis and diabetes [10,11]. The existence of social support denotes the availability of people around us on whom one can depend and people who reciprocate our values and love [12]. Social support strengthens the capacity to withstand stress and overcome frustration.

Department of Defense Survey of Health Related Behaviours among Military Personnel reported substantial substance use and perceived high stress in the armed forces. Stress at work or in the family was an important predictor of substance use among military men [13].

Research in field of social support in alcoholism have revealed its wider role in understanding risk factors related to alcohol dependence syndrome and wider implication in improving treatment response by reducing relapses. It becomes imperative to look at the extra treatment factors beyond the confines of treatment setting which influence the outcome in alcohol dependence syndrome. Social support is one of such extra treatment variable. Research in India in field of social support in relation to alcohol dependence syndrome is meager. Army is a large community where personnels are closely bonded together through sense of we-ness and brotherhood. So it becomes imperative that social angle of recovery must be assessed and utilized in treating alcoholics for better outcome. Keeping this in view present study was taken up to understand social support variable in alcohol dependence syndrome treatment outcome in armed forces settings. The findings in the study would enable us to evolve therapeutic programme with better outcome involving social support and network members as shown in several western studies [14,15].

Materials and Methods

An approval was obtained from the hospital ethics committee before the commencement of the study. The cross-sectional study was carried out in the Department of Psychiatry, Base Hospital Delhi from 01 Jan 2014 to 31 Dec 2014. The patients were all consecutive male adults admitted as cases of alcohol dependence syndrome for review. Inclusion criteria was patient must be meeting criteria for alcohol dependence syndrome as per International Classification of Diseases 10 (ICD 10). Exclusion criteria were patient with concurrent neurological disease resulting in cognitive deficit and any other major psychiatric illness other than alcohol dependence syndrome. Cases with concurrent nicotine dependence were not included. They were informed about the details of the study and informed consent was obtained from each participant before undertaking the research.

Those who satisfied the selection criteria (N=55) were selected for the study. Patient meeting the inclusion criteria were divided into two categories.

Those that had been abstinent throughout the review period of six months formed abstinent group (n= 18).

Those who had been taking alcohol during review period formed relapsed group (n=37).

Detailed clinical evaluation of individuals was carried out and details were recorded as per specifically designed format which included their socio-demographic profile, alcoholic status along with presence or absence of withdrawal features routine lab investigations, treatment received and psychosocial problems related with alcohol. Relapse group were detoxified (N=37) and when physically and psychiatrically stable entered next stage of study prior to which all medications were withdrawn. In the next stage social support of patient was ascertained. Social support was assessed using (A) social support questionnaire (SSQ). It is 18 item questionnaires. Each item has four option which range from agreement (scored as 1) to extreme agreement (scored as 4) higher score indicate more social support to the individual. It was developed by Nehra et al., [16]. (B) Social Provision Scale (SPS). This is 24 item scale. Each item of scale has 4 option which range from disagree, agree, strongly disagree, strongly agree measuring six social provision guidance, reliable alliance, reassurance of worth, opportunity of nurturance, attachment and social integration in relation with current friend family members, co-workers and community worker. A score of each social provision is derived such that a higher score indicates that individual is receiving that provision. Total social support is then reflected adding all six provisions score [17]. Relapsed group were assessed for social support after stabilization of withdrawal features by administering SSQ and SPS in 1or 2 settings. Each patient needed about 2 to 4 settings for complete evaluation.

Statistical Analysis

Data were tabulated and statistically analysed by using chi square test. Comparison of SPS and SSQ in different socio economic groups was calculated using Rank ANOVA test where applicable. p-value <.05 was taken as significant. Comparison of social provision in abstinent and relapse group was done using MANN-WHITNEY U-TEST.

Results

There was no significant difference between the relapsed and abstinent groups with regards to age, marital status, educational status, occupation, current place of work and income. This suggests that difference between the group that were obtained on dependent measures cannot be attributed to influence of any of above variable. It also suggests that group were comparable. [Table/Fig-1] denotes the comparison of SPS and SSQ in different socio- economic groups. Professional and semi-professional perceived better social support than clerks and skilled worker in SPS though SSQ scores were not statistically significant. While considering educational background individuals with professional degree perceived greater social support than who were below matriculate or beyond matriculate though the income bracket did not have any significant statistical difference.

Comparison of sps and ssq in different socio economic groups Data are expressed as median and range Statistically significant difference (p<0.05) a=from group i, b=from group ii

| Group I | Group II | Group III | p-value |

|---|

| OCCUPATION |

|---|

| SPS | PROF. + SEMI PROF . n=19 | CLERK + SEMI SKILLED n=19 | UNSKILLED n=17 | RANK ANOVA P< |

| 78.0 (53.0-96.0) | 72.0 (59.0-84.0) | 73.0a (47.0-96.0) | 0.05 |

| SSQ | PROF. + SEMI PROF . n=18 | CLERK + SEMI SKILLED n=19 | UNSKILLED n=17 | RANK ANOVA P< |

| 57.0 (43.0-66.0) | 52.0 (30.0-68.0) | 51.0 (33.0-64.0) | NS |

| EDUCATION |

| SPS | PROF n=11 | BEYOND MATRICULATE n=25 | NON MATRICULATE n=19 | RANK ANOVA P< |

| 78.0 (59.0-96.0) | 74.0 (59.0-96.0) | 63.0ab (47.0-75.0) | <.05 |

| SSQ | PROF n=11 | BEYOND MATRICULATE n=25 | NON MATRICULATE n=19 | RANK ANOVA P< |

| 54.0 (45.0-62.0) | 54.0 (30.0-68.0) | 52.0 (33.0-64.0) | NS |

| INCOME |

| SPS | >Rs. 45000 n=14 | >Rs.25000-Rs.45000 n=22 | <Rs.25000 n=19 | RANK ANOVA P< |

| 74 (55.0.86.0) | 72 (47.0-89.0) | 75 (63.0-96.0) | NS |

| SSQ | >Rs. 45000 n=14 | >Rs.25000-Rs.45000 n=22 | <Rs.25000 n=19 | RANK ANOVA P< |

| 53 (41.0-62.0) | 55 (30.0-68.0) | 54 (43.0-64.0) | NS |

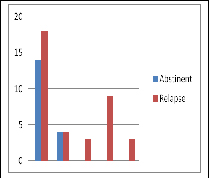

Individual’s subjective evaluation of severity of alcohol problem as to how much bothered or troubled they were due to their drinking [Table/Fig-2] revealed those who were less bothered about their alcohol problem scored significantly high in SPS (Z=3.87, p<0.001) and SSQ (Z=3.87, p<0.001). This can be understood in light that drinking problems increase life stress in soldiers by causing job, health related, disciplinary and interpersonal problems and reduce social resources by causing peer, superiors, family and relatives to withdraw.

Comparison between Not At all vs Rest

| DEGREE OF TROUBLE/BOTHERATIONDUE TO ALCOHOL RELATED PROBLEMS | ABSTINENT | RELAPSE |

|---|

| N=18 | N=37 |

|---|

| 1 | NOT AT ALL | 14 | 18 |

| 2 | SLIGHTLY | 4 | 4 |

| 3 | MODERATELY | 0 | 3 |

| 4 | CONSIDERABLY | 0 | 9 |

| 5 | EXTREMELY | 0 | 3 |

|

X2 = 4.22 & df =1 p < 0.05

A comparison was made of perceived social support in individuals who had positive family history of alcoholism (FH+, n=22) with individuals who had negative family history of (FH—, n=22) in SSQ and SPS score comparison between two groups in SPS (Z=.23, p=.8185) and SSQ (Z=.22, p=.8273) was not significant.

Correlation between quantity of alcohol taken in relapsed group one month prior to admission was not significantly related to SPS (r= -0.308, p= .0641) and SSQ (r = -.08020). Though there was inverse correlation between support it was not significant.

Correlation between duration of use in relapse group with SPS (r =0.172, p=0.3081) and SSQ (r =0.236, p=O.1589) was not significant. Similar correlation between duration of dependence in relapse group with SPS (r=0.669, p=0.6864) and SSQ (r =0.0442, p=0.794) was not significant.

In abstinent group duration of use was not statically significant with SPS (r = 0.264, p = 0.2901) and SSQ (r = -0.435, p=.0710). Duration of dependence in abstinent group was not statistically significant with SPS (r= -0.135, P=0.5935) and SSQ (r =.484, P=.0419). Though there was inverse correlation between duration of use and dependence with the abstinent group with social support it was not of statistical significance.

[Table/Fig-3] shows comparisons of social provision score in abstinent and relapsed group in all six social provisions. All provisions were statistically significant in relapsed and abstinent group.

| COMPARISON OF SOCIAL PROVISION IN ABSTINENT AND RELAPSE GROUP |

|---|

| SOCIAL PROVISIONSCALE | ABSTINENT | RELAPSE | SINGIFICANCE |

|---|

| MEDIAN | RANGE | MEDIAN | RANGE | Z | P |

|---|

| 1 | GUIDANCE | 15 | 12-16 | 12 | 9-16 | 2.67 | <0.01 |

| 2 | REASSURANCE OF WORTH | 15 | 13-16 | 11 | 5-16 | 3.77 | <0.001 |

| 3 | SOCIAL INTEGRATION | 14 | 12-16 | 12 | 7-16 | 3 | <0.01 |

| 4 | ATTACHMENT | 13 | 10-16 | 12 | 5-16 | 2.18 | <0.05 |

| 5 | NURTURANCE | 15 | 10-16 | 12 | 10-16 | 2.67 | <0.01 |

| 6 | RELLIABLE ALLIANCE | 14 | 9-16 | 12 | 5-16 | 2.5 | <0.05 |

Discussion

The present study examined role of social support in treatment outcome of alcohol dependence syndrome and to see its correlation with socio-economic data. Research in India in field of alcoholism in context of psychosocial intervention is meager [18]. According to stress support model [17] Alcoholism would be viewed as potentially controllable stressor requiring personal coping effort on part to overcome it. Mechanism hypothesized to produce relapse share an emphasis on interplay between relapse risk factors (perceived stress, negative affect, positive expectations about substance use) and relapse protective factors like (coping skills & self efficacy) [19]. Social support enhance people belief in their ability to facilitate effective coping behaviour through mediation of self effective coping behaviour and less negative affect during time of stress.

In this study, patients were all from defence background. Out of which, 94.54% were married yet perception of social support distinguished abstinent and relapse groups as measured by SPS (Z=3.36, p<0.001) and SSQ (Z=3.77, p< 0.001). [Table/Fig-3] shows comparison of social provision score in relapse and abstinent group in all six social provisions. Reassurance of worth was important provision to buffer against stressor associated with alcoholic status. Being perceived by unit or platoon members and leaders as capable and worthy may enhance self confidence of an alcoholic to overcome his drinking problem. A soldier immaterial of his skill whether he is a cook or a housekeeper or a combatant or an animal handler or a washerman if is valued by his family members or relatives is likely to overcome his addiction. High level of reassurance of worth to recovering alcoholics significantly lengthened their time to readmission by reducing relapses [14].

In present study, social integration was perceived significantly in better manner in abstinent group. An alcoholic who is not marginalized or stigmatized in the unit and integrates well with the fellow members is likely to have better treatment outcome and abstain. It’s pertinent that the self stigma which an alcoholic carries with him is dealt during the group therapy session or the Alcohol anonymous meets. This will help him in coming out of his drinking problem and improve his endeavors to integrate well or get well with others. Social integration or sense of comradeship in unit or platoon buffers against relapse. Thus preventing social isolation of an alcoholic in his unit, family and social setting will help him to overcome his addiction. Social integration strengthens motivation to abstain from drugs and alcohol post-treatment in adolescents [20]. Social disintegration has been reported in heavy drinkers [21]. Hanson reported few contact, friends and relatives and lower social participation in heavy drinkers. Broader public health message initiatives might need to focus on dispelling the commonly held “skid row” alcoholic stereotypes [22–24]. Stigma and discrimination exists against people with drug dependence [25–27]. They are often looked down upon [28]. Patients suffer greater psychological pain for stigma than the mental illness or addiction itself [29,30] and it delays path to care, recovery and rehabilitation [31]. Stigma against mental illness is highly prevalent in Indian armed forces [32].

Reliable alliance (the assurance that other can be counted upon for tangible assistance) was also statistically significant across abstinent and relapsed group. Reliable alliance was reported to have to have buffering influence on financial stress and alcohol involvement [33]. Army has age old system of forming a buddy for all its soldiers. It is important that a buddy be familiar with signs of stress and alcoholism in his mate and it can prevent full relapse in his mate through timely referral. A buddy is of usually of same background and village of the soldier and preferably should be non drinker. As soldiers get frequently relocated this alliance may get broken and should be re-established soon.

Relational provision of guidance does contribute to skill acquisition. Alcoholics post discharge & treatment face range of challenges and strains. A number of new skills must be acquired and new routines need be established. The relational provision of guidance does contribute to skill acquisition. Direct advice from experienced superiors, partners and co-workers, informal sharing with other young colleagues may speed up learning process which would otherwise depend on trial and error. Abstinent group in our study perceived provision of guidance better than relapsed group and could perhaps abstain. Guidance through non drinkers or pro abstainers to achieve and maintain sobriety has been found useful in network therapy [34]. They not only provide hope, coping strategies but are also useful role model in testing periods.

Nurturance represents a belief that others need to rely on one. For individuals facing loss of valued role opportunity of nurturance appears to be important in maintain self esteem and health [35]. Alcoholics have interpersonal difficulties and are accompanied by sense of role loss as there is social and occupational devaluation. Thus it makes sense that recovering alcoholic should benefit from relationship in their life which gives them sense of worth and purpose. Perhaps individuals whose sense of self worth is bolstered by others take better care of themselves and therefore abstinent group were able to abstain.

Attachment (emotional closeness from which one derives a sense of security) is most often provided by spouse but may also be derived from close friendship or family relationship. It was better perceived in abstinent group. Enduring romantic relationships generally are expected to be the most important attachment relationships in adult life. Marital relationships can be a catalyst towards retaining or disrupting commitments to abstinence. Abstinence improves relationship satisfaction by reducing the emotional distress, improving shared activities, problem solving. Family involvement in patient care is important in recovering alcoholics but in military often separation from family has to be endured as a result of postings or deployment. Sometimes families are not staying together due to career ambition of spouse or shortage of accommodation. Co-opting family into treatment process becomes important and has longlasting benefit through attachment support. One study had found that unmarried alcoholics were nearly twice as likely to relapse to drinking as married alcoholics [36]. Another study reported that demographic variables, such as being single and having a lower education, were the best predictors of poorer drinking outcomes [37].

Every individualized treatment plan should include assessment of soldier’s social support in the environment to which he will return. The assessment should determine whether human network in unit setting and personal life is favourable or unfavourable to patient’s social and emotional growth. Soldier should be educated to mobilize their own support system in times of stress and mental worry. Special instructions to the environment in which soldier returns should be passed on an individualized basis in discharge instructions with emphasis on methods to increase his integration, employments increasing his self worth and increasing association and guidance through pro-abstainers members. There should be strong efforts to deal with self stigma and environment attached stigma in cases of alcoholics. The idea is to sustain and enhance treatment gains achieved during hospital stay. Development of network therapy is important and involves training network to provide specific type of support and patient how to derive such support from significant others. All of which will have important bearing on treatment outcome in alcohol dependence syndrome. These results are consistent with the work of Billing and Moose [38] and Rosenberg [39]. Billing and Moose demonstrated that stress coping response and family environment as post treatment factor was important predictor of alcoholism treatment response [38]. Rosenberg reported in alcoholics greater perceived and received support greater use of coping skills and fewer negative events in abstinent subject compared to relapse [39].

There are certain limitations in our study. First, the demographic homogeneity of the sample may have resulted in limited variance in responses and outcomes. The results in this study are based on cross-sectional study. Therefore it is not possible to determine causal relationship between high perception of social support and abstinence. Our Study didn’t account for confounding variables like extraversion/introversion [40] or social investment [41] which influence perception of social support. Community health interventions should be broad based and should include both home based and workplace awareness initiatives. Rich and well integrated support system in Army should be utilized for this. Findings have important implication for treatment programs as social support factors are amenable to treatment intervention during treatment and as a part of aftercare. Focus of effort should be to develop methods to intervene in support network available and enhance support from colleagues, peers family and friends. Scope also involves identification of patients who may experience decline in support after discharge and are more at risk for poorer outcome and should be focus of network therapy which in our study were patients with health related problem & interpersonal problem due to alcohol use and of lower socio-economic status.

Conclusion

The findings of this study highlight the potential therapeutic importance of social support in treatment outcome of alcohol dependence syndrome. Several alcohol-dependent patients have dysfunctional workplace and family relationship. Hence including pharmacological interventions with appropriate psychosocial therapies focusing on improving social network of the patient may provide better outcome than either of these therapies given alone. From the study it can be concluded that abstinent group perceived better social support than relapsed group and patient in upper socio-occupational status and less alcohol related problems perceived more social support than patients with lower socio-economic status and more alcohol related problems. However future studies should include larger sample size and be longitudinal in nature. They should incorporate factors like extraversion and introversion which influence perception of social support and also take into account psychiatric co-morbidity like depression while studying social support in treatment outcome of alcohol dependence syndrome.

X2 = 4.22 & df =1 p < 0.05