The global population is aging and there is increased prevalence of chronic diseases associated with the elderly such as Alzheimer’s disease [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) there were 26.6 million individuals worldwide in 2006 with Alzheimer’s disease [2] and it is projected that by 2025 there will be 34.0 million persons living with the disease [3]. Data from developing countries indicate an estimated ≥5% age-adjusted prevalence of dementia in persons 65 years and older in Latin American and Asian countries, and 60% of these individuals have Alzheimer’s disease [4]. It is reported that greater than 50% of persons with Alzheimer’s disease reside in developing countries and this is projected to increase to over 70% by 2025 [2]. One of the primary risk factors of Alzheimer’s disease is advancing age and the risk of acquiring the disorder doubles for every five years after an individual has attain an age of 65 years [5].

There is no preventative or curative measures for Alzheimer’s disease, but there are a number of pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches such as psychosocial intervention and caregiving that have been documented to treat the symptoms of the disease [6,7]. While these treatments have gained some success in alleviating the symptom of the disease, they are not preventative nor are they able to arrest or reverse the neuropathological and pathophysiological changes related to the disease [8].

Cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease affect their ability to function independently and their quality of life. In a recent study, the overall quality of life scores for persons with Alzheimer’s disease who attended an Adult Day Program were similar to those without the disease [9]. Other studies have reported that worsening of the quality of life of individuals with Alzheimer’s disease is related to deterioration in cognition measured by mini-mental state examination [10,11] and being depressed [12].

The management of patients with Alzheimer’s disease is essential and the caregiver play a key role in providing critically needed care for these patients [13]. Caregivers such as unpaid family members or hired individuals perform a number of comprehensive tasks, and so the physical and emotional demands of caregiving are high. The life of the caregiver and other members of the patients’ family are usually negatively impacted in aspects such as economic, physical, psychological and social [14]. Studies have shown that the quality of life of the caregiver is influenced by the nature of the disease and is improved by his or her experience, the therapy of the patient and the strategies adopted [12,15,16]. Furthermore, knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease and the attitude of family members will influence their decision making regarding early diagnosis and treatment [17].

It important to assess the youth population’s attitudes and feelings towards those within our society who are diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease and no previous study has been conducted in Trinidad in this area. This study compared the knowledge and of pre-healthcare and non-medical students towards patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

Materials and Methods

The period for collecting data was between the months of February to August, 2012. The target population for this study was undergraduate students over the age of eighteen years from The University of the West Indies, St Augustine Campus. The study population involved pre-healthcare and non-medical undergraduate students. Pre-healthcare students comprised of those from medicine, dentistry, pharmacy, nursing and veterinary while non-medical students were those from all the other existing faculties of the University. Quota sampling was used where 691 questionnaires were completed (369 from pre-healthcare and 322 from non-medical students). Questionnaires were constructed and disseminated to students of both populations (pre-healthcare and non-medical students). The 28-item questionnaire utilised consists of closed-ended questions and some based on a scale rating (see Appendix). Approval from the ethics committee was sought before any questionnaires were distributed.

At the onset of the study, a pilot study was done in order to ensure the questionnaire (instrument) had face validity through the vetting of the questionnaire with faculty members and a small group of students to ensure the questions did not pose any problems. The pilot study was also performed in order to get estimates of variances and differences in the means that are necessary in the use of construction of the sample size.

In order to achieve Type I error rate of 0.05 and power of 90%, and assuming the population mean for one population is 39.95 and the other is 39.00, and a common standard deviation of 0.95, a sample size of at least 22 in each group was required. More than 22 from each of the groups were sampled.

In assessing the students’ knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease, the definitions received were graded on a point system, 0 to 3 in which:

0 = no knowledge about Alzheimer’s disease,

1 = very little knowledge about Alzheimer’s disease,

2 = fair knowledge about Alzheimer’s disease and,

3 = great knowledge about Alzheimer’s disease.

One point was awarded if the definition included and was similar to any of the following:

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive, degenerative disorder that attacks the brain’s nerve cells, or neurons, especially the frontal and temporal lobes (neuron death),

It is the most common form of dementia; resulting in loss of memory, thinking and language skills, and behavioural changes usually affecting individuals > 65 years.

It is characterized by the finding of unusual helical protein filaments in nerve cells of the brain called neurofibrillary tangles. It is associated with amyloid protein in neurons and low acetylcholine levels.

The Chi-square test of independence was also used to determine which knowledge variables (as a risk factor of Alzheimer’s disease: age, genetics, fatty diet, inadequate exercise, alcohol abuse and cigarette smoking) were independent of student’s status. The assessment of the attitude of the undergraduate students towards patients with Alzheimer’s disease was performed using questions 11 to 20, each based on a Likert 5 Point Scale (see Appendix). The totals for these questions were totalled and this provided the score for the Attitude Scale. The sum of the answers was calculated with the maximum value being fifty, and is equivalent to the most positive attitude. Crinbach’s alpha for this scale was 0.463.

Data were analysed using the computer software SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) version 16.0 for Windows.

Results

Demographics

Of the 691 students sampled, 369 (53.4%) were from the medical faculty and 322 (46.6%) were from the non-medical faculties. The sample consisted of 292 males and 399 females, with 53.4% of the males from the medical faculty and 46.6% of the males were from the non-medical faculties. Likewise, 53.4% of females were from the medical faculty while 46.6% of the females were from the non-medical faculties. It was found that 32.4% of the pre-healthcare students and 31.5% of the non-medical students were within the age group 18-22 years.

Alzheimer’s Disease Relations

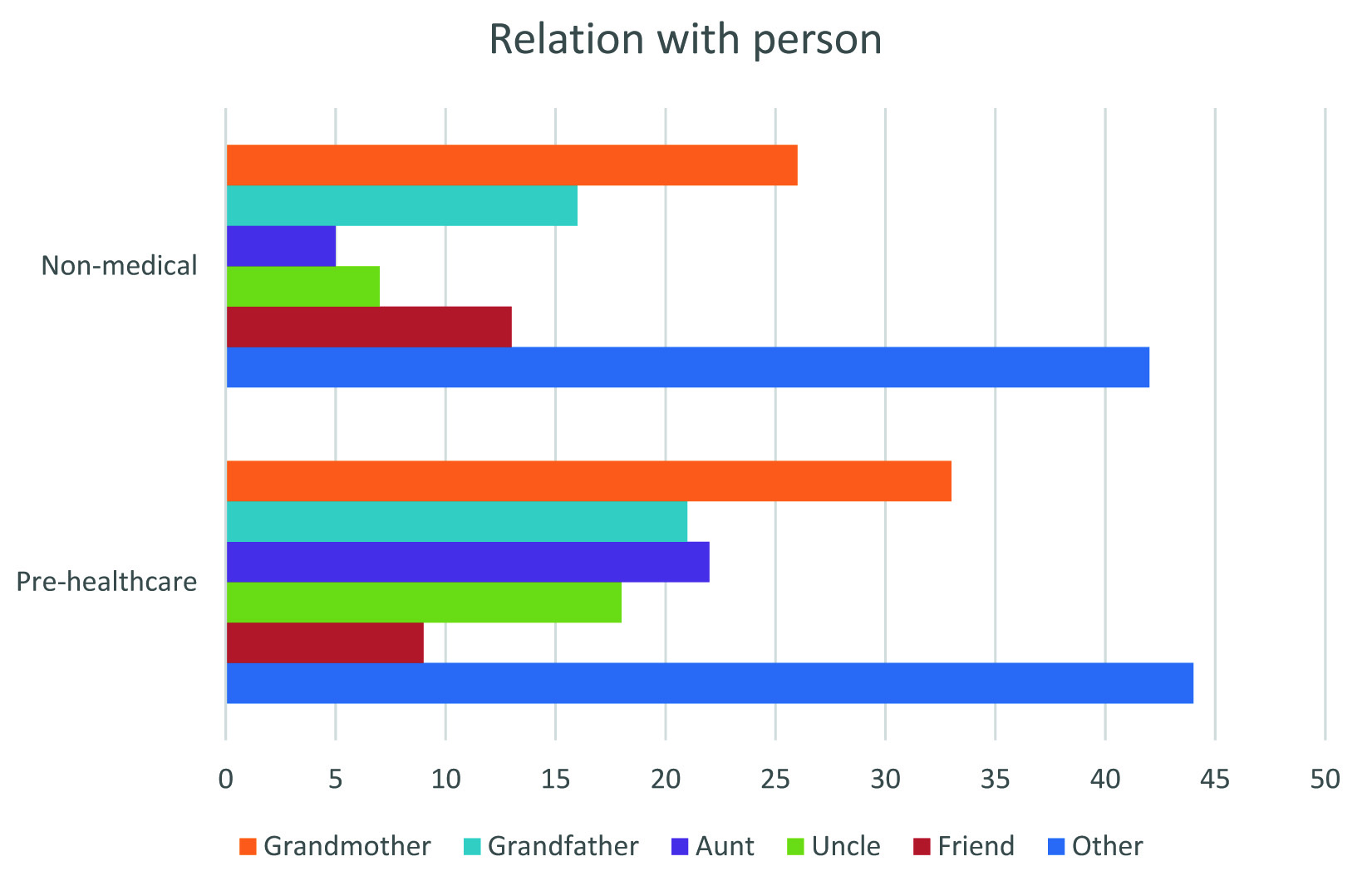

A total of 467 (67.6%) students did not know anyone with Alzheimer’s disease. Of this group, 48.7% were non-medical. Much fewer were familiar with patients of Alzheimer’s disease with 18.7% (129 students) from the medical faculty knew somebody with the disease and only 29.5% non-medical undergraduates were acquainted with someone with the illness. [Table/Fig-1] demonstrates percentages of students in both groups who knew someone with Alzheimer’s disease. Persons’ family members are not only closely related but in close and regular contact. Grandmothers of both groups were dominant with 4.8% and 3.8% for pre-healthcare and non-medical students respectively. Relations such as grandfather, aunt, uncle and even friend all were 3.0% and less for the two categories of students.

Relation to persons with Alzheimer’s disease

In this study, 84.9% endorse the disclosure of the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease of a family member to others. They cited that the reason for disclosure of the diseases is to increase awareness (50.9%) and to receive support (49.1%) from others. Furthermore, the majority (82.2%) of the students would disclosure the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease to others if they had the disease.

Attitude

The averages for both pre-healthcare and non-medical students were compared and it can be seen that the former do have a more positive attitude towards Alzheimer’s disease patients with a mean of 39.95 compared with 39.04 for non-medical students.

A 2-sample t-test was performed to determine whether the means were significantly different assuming equal variances for both populations since Levine’s test for the equality of variance gave both variances being equal (t=2.123, p-value=0.275 > 0.05). The mean attitudes of pre-healthcare and non-medical students at the 5% level was significant (p-value = 0.034 <0.05).

The means for attitude were tested to ascertain any difference based on the premise that the respondent knew someone with Alzheimer’s disease. The mean attitude for those who knew someone with Alzheimer’s disease was 40.27 while the mean attitude for those who did not know anyone with the disease was 39.10. A higher mean meant that the person had a better and more caring attitude towards someone with Alzheimer’s disease. Non-medical students have a slightly less positive attitude towards persons with Alzheimer’s disease (an average attitude of 39.93) as compared to pre-healthcare students (40.47).

The respondents felt that spouse (37.1%) would offer the best care to the Alzheimer’s disease patient during the latter stages followed by daughter (29.9%), son (26.4%) and other family member (6.6%).

Knowledge

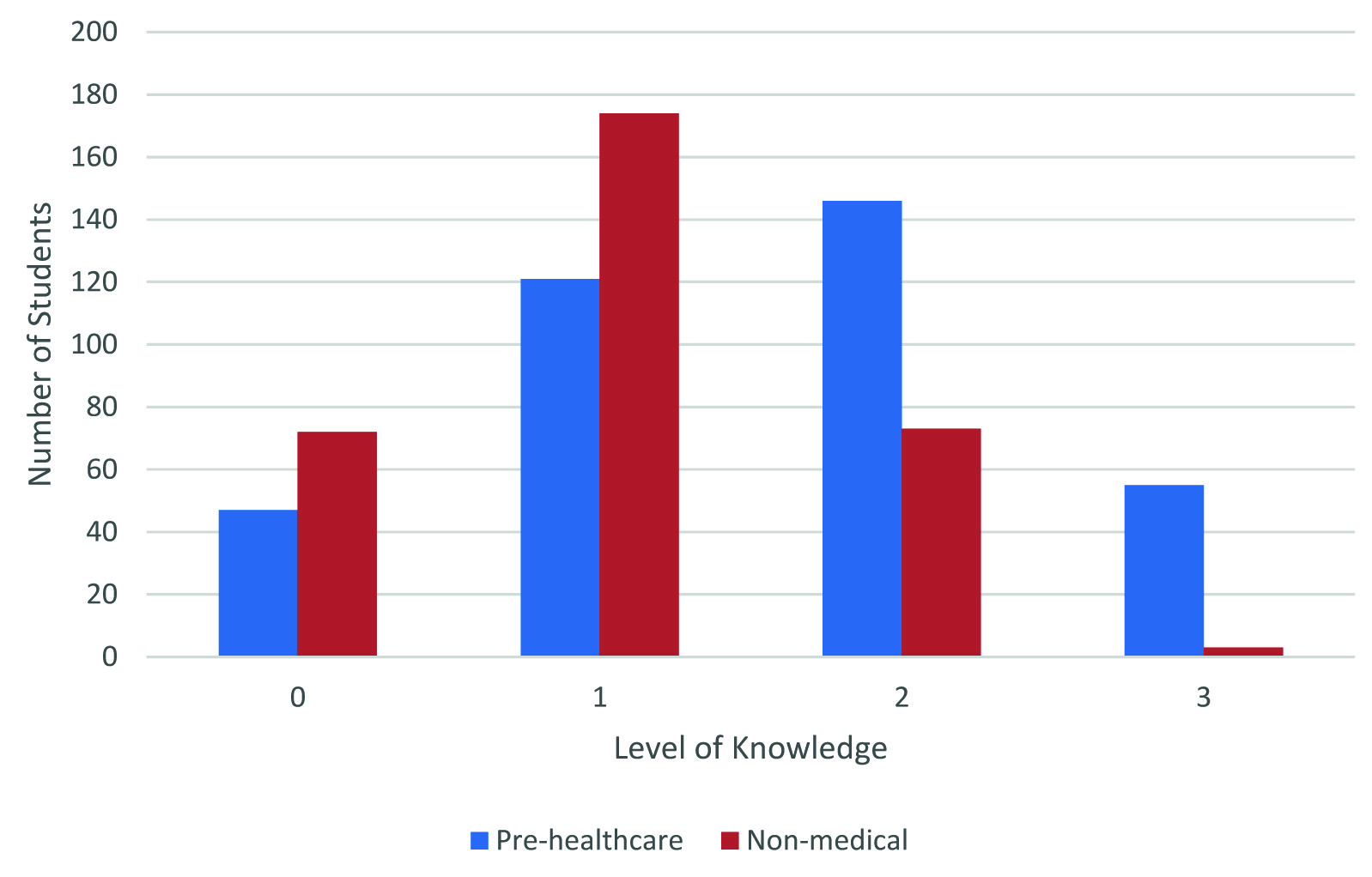

[Table/Fig-2] shows the rate of knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease (on a scale of 0 to 3) versus student’s status tabulated results. Overall, 40.01% of the undergraduate students in the study had great knowledge (score 3) or fair (score 2) knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease, with that of pre-healthcare students being satisfactory (54.47%). A more significant number of undergraduate pre-healthcare students had great knowledge (14.9%) or fair (39.54%) knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease compared to undergraduate non-medical students. More non-medical students had very little knowledge (score 1, 54.04%) or no knowledge (score 0, 22.36%) of Alzheimer’s disease.

Rate of knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease versus student’s status

The variables knowledge and status of student were dependent (χ2= 82.915, df = 3, p-value = 0.0001). Knowledge of the risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease such as age, genetics and fatty diet were dependent on the status of the student (whether they are pre-healthcare or non-medical).

Predictive Testing

In this study, it was noted that more than one-half (54.4%) of the respondents had fear of being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in their later years and 35.6% identified age as a risk factor while 34.0% suggested genetics. A total of 568 (82.2%) of the students wished to take advantage of predictive test for Alzheimer’s disease [Table/Fig-3]. It was found that 292 (51.4%) and 276 (46.6%) were pre-healthcare and non-medical undergraduate students respectively with reasons for agreeing such as wanting to know and preparation for future. However, 106 (15.3%) stated that they would not take the test. Only 21.7% of those who refused testing cited denial whereas 45.9% would be afraid to know if they would be predisposed to the disease.

Students’ views on taking advantage of predictive testing

| Take advantage ofpredictive testing | Pre-healthcare | Non-medical |

|---|

| Yes | 292 (42.2%) | 276 (39.9%) |

| No | 74 (10.7%) | 32 (4.6%) |

Discussion

The study consisted of undergraduate non-medical and pre-healthcare students and the majority were females and in the 18-22 year group. Approximately one-third of the undergraduate students were acquainted with persons with Alzheimer’s disease with more pre-healthcare students being familiar with individuals with the illness than their non-medical counterparts. The persons with the illness were close relatives of the students and more likely to be grandmothers as well as grandfathers, aunts, uncles and friends. In a study which examined the knowledge and attitude of the French public with regards to Alzheimer’s disease, 26.9% of the respondents know someone with Alzheimer’s disease who was either a family member or close acquaintance [18].

Knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease and a good understanding of the risk factors of the disease are generally considered to be essential for care of patients. In our study, 40.01% of the undergraduate students had great or fair knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease. A more significant number of undergraduate pre-healthcare students had great or fair knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease compared with non-medical undergraduate students. The greater knowledge of the pre-healthcare students about Alzheimer’s disease could be as a result of their prior exposure to information in the medical curriculum or in science classes in high school. The lower knowledge scores of the non-medical students may suggests that responses offered showed incomplete or lack of understanding of established facts documented in the literature about Alzheimer’s disease. It is important to note that the students in our study are in their first year and may have limited exposure to facts of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia care in their training.

The disclosure of the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease by family members or caregivers to the patient is a contentious issue. In our study, pre-healthcare students exhibited a more positive attitude and were more caring towards persons with Alzheimer’s disease compared with to non-medical students, although the difference was not statistically significance. These students support the view that patients with Alzheimer’s disease should be informed about their diagnosis, and that caregivers including family members being adequately informed about the illness can make a significant difference in the lives of these patients. The respondents indicated that spouse (37.1%) would offer the best care to Alzheimer’s disease patients during the latter stages followed by daughter (29.9%), son (26.4%) and other family member (6.6%). The undergraduate students who did not support the disclosure of the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease to the patient may wish to use denial as a defence mechanism to cope with such devastating news for their loved ones [19].

The results of our study differed from that of Maguire and colleagues who studied 100 consecutive family members who are caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and accompanied them to a memory clinic [20]. They reported that 17% indicated that the patient should be informed about the diagnosis of the disease while the remainder indicated the opposite. The main reason for the position of the latter group is this would negatively affect the patient who may become upset and depressed. The finding of the latter study is congruent with that by Puce and colleagues involving 71 closest relatives of patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease for the first time who were interviewed. They reported that 60.6% were not in favour of their loved one being fully informed that they had Alzheimer’s disease [21]. The justifications of this position by relatives include their own emotional difficulty in accepting and coping with the psychological reaction of their loved one and the risk of onset and possible worsening symptoms of depression in the patient [21]. In our study, 84.9% endorse the disclosure of the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease of a family member to others. They cited that the reason for disclosure of the diseases is to increase awareness (50.9%) and to receive support (49.1%) from others. Furthermore, the majority of the students would disclosure the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease to others if they had the disease.

In our study, it was noted that more than one-half (54.4%) of the respondents had fear of being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease in their later years and 35.6% identified age as a risk factor while 34.0% suggested genetics. This shows the lack of knowledge of relevant information about the disease among the undergraduate students. The findings of our study were not in congruent with a study of 1245 epidemiologically representative persons in Germans, where just over one-half (54%) reported that age was a major risk factor of Alzheimer’s disease [22]. In terms of developing the disease, just under three-quarters (70%) would like to be informed together with a close friend or relatives if they were diagnosed with the disease [22].

In the last decade genetic tests that identify an asymptomatic individual’s susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease has been increasing [23]. The majority of students in our study wanted to take the predictive test for Alzheimer’s disease if it was offered and this group consisted mostly of pre-healthcare students. These individuals were keen on knowing whether they were at risk for the disease so that they would be better prepared in the future. The undergraduate students who would refuse to take the predicted test had a lower level of concern for Alzheimer’s disease risk and cited reasons such as fear of knowing if they were predisposed to the disease and being diagnose with the illness in the future, and choosing to live in denial. In a study of 314 African Americans and Caucasian first degree relatives of Alzheimer’s disease patients who were surveyed about their concerns about developing Alzheimer’s disease, knowledge of genetic testing and risk of the disease as well as reasons for seeking genetic testing, the former group had less knowledge about established facts concerning Alzheimer’s disease and genetic testing [24]. African Americans reported less anxiety and concern regarding the possibility of developing Alzheimer’s disease [24], a finding which was consistent with a previous study by Robert and colleagues where this group perceived Alzheimer’s disease as a lesser threat compared to their Caucasian counterpart [25].

At risk individuals may pursue genetic susceptibility testing for early onset Alzheimer’s disease due to a number of reasons including anxiety relief, financial planning and organizing family affairs, prevention and medical treatment of the disease [24,26]. Our results suggest that undergraduate students were in favour of seeking genetic susceptibility testing as they are generally concerned about the possibility of developing Alzheimer’s disease in the future. Pre-healthcare students were more knowledgeable of established information about Alzheimer’s disease. The lack of knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease and genetic susceptibility testing for the illness may contribute to undergraduate students, more so non-medical to make decisions regarding predictive testing without being fully aware of its benefits, limitations and possible risks.

Conclusion

The study showed that the undergraduate pre-healthcare students had moderate knowledge of Alzheimer’s disease. It is important that throughout their career undergraduate pre-healthcare students should acquire higher levels of knowledge and increased understanding of Alzheimer’s disease and other-related dementia illnesses which will equip them as future health professionals to meet the challenges of caring for the increasing number of cognitively impaired patients as the world’s population ages. The active involvement of these pre-healthcare students in training, the sharing of information and ideas as well as reflection on the challenges experienced by the patients and their caregivers may provide a way to support an improved quality of life for persons with the illness.