Introduction

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) is the most serious hyperglycaemic emergency in patients with type 1 and type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (DM) and is associated with significant morbidity and mortality [1]. DKA is responsible for more than 500,000 hospital days per year [2,3]. It is conceptualized that DKA occurs most often in patients with Type 1 diabetes but this is not true. DKA is also reported in type 2 diabetes; however, it rarely occurs without a precipitating event [4-6]. National Centre for health statistics showed that most patients with DKA were between the ages of 18 and 44 years (56%) and 45 and 65 years (24%), with only 18% of patients <20 years of age. Two-thirds of DKA patients were considered to have type 1 diabetes and 34% to have type 2 diabetes; 50% were female and 45% were nonwhite [2]. Another previous study by Adhikari et al., also showed predominance of type 2 diabetes mellitus (62.8%) as compared to type 1 diabetes mellitus (37.8%) who presented with DKA [7].

DKA consists of the triad of hyperglycaemia, ketosis, and acidemia. An arterial pH of less than 7.35, a Serum Bicarbonate (HCO3-) value of less than 15 mEq/L, and a blood glucose level of greater than 250 mg/dl with a moderate degree of ketonaemia and/or ketonuria (as determined by nitroprusside method) are necessary for the diagnosis of DKA [8].

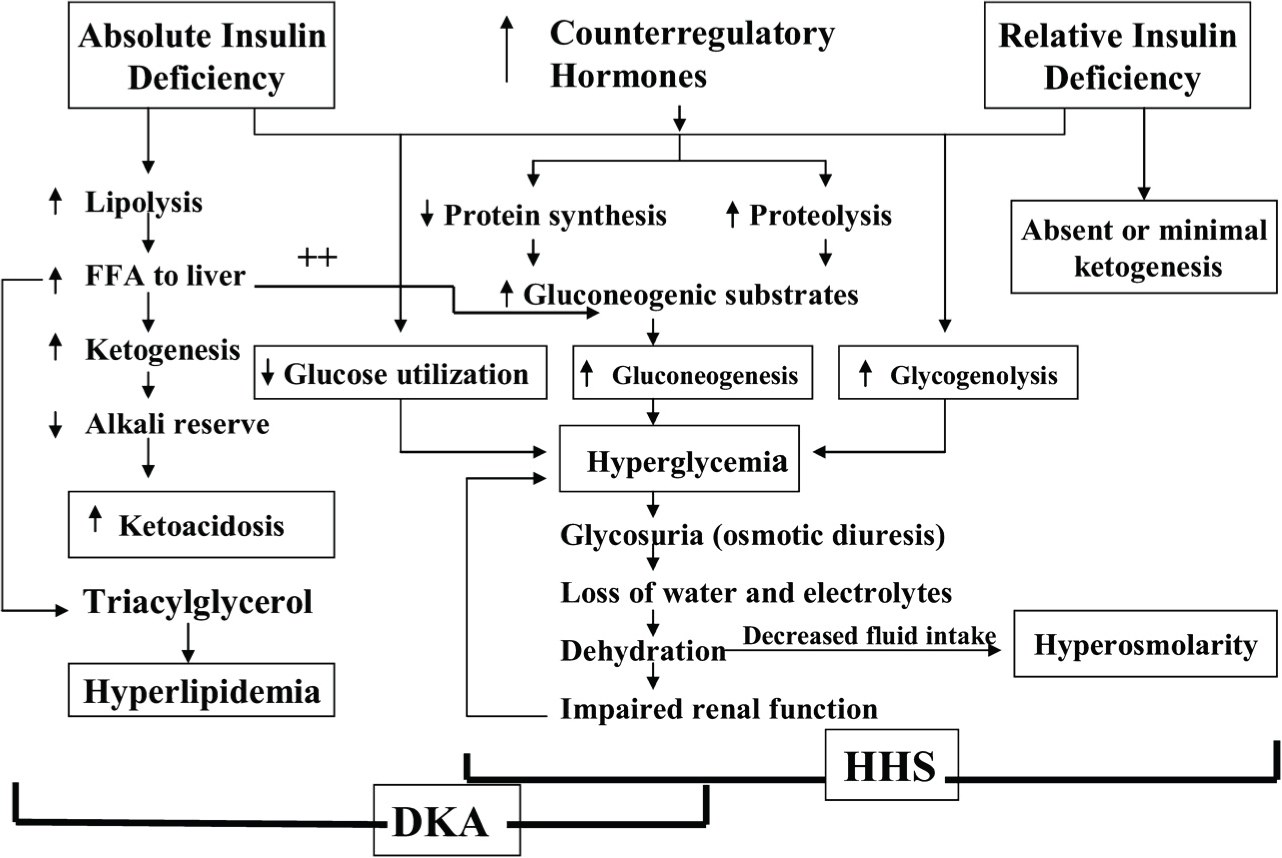

Pathophysiology of DKA involves reduction of the effective insulin concentrations in the body which are not able to match the glycaemic overload either due to high intake or increased concentrations of counter-regulatory hormones (catecholamines, cortisol, glucagon, and growth hormone). This imbalance leads to hyperglycaemia and ketosis. Hyperglycaemia can be due to increased gluconeogenesis, accelerated glycogenolysis, or impaired glucose utilization by peripheral tissues [Table/Fig-1][9]. DKA is a catabolic state and there is an alteration of protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. The anion gap is increased from normal (8-12 mmol/L) in DKA. It has heterogeneous clinical presentation. Increased mortality and fatal complications are seen in untreated patients.

DKA usually presents with symptoms like nausea, vomiting, pain abdomen. They may also have increased thirst and polyuria. On examination usually a fruity odour can be smelled and the breathing is typical of DKA, rapid shallow kussmaul breathing. Severe cases may present with hypotension, altered sensorium. Features of the precipitating cause may also be present. A study was done by Munro et al., who noticed the frequency of nausea and vomiting (86%), pain abdomen (27%), polyuria/polydipsia in 24% of patients [10]. Umpierrez et al., did a study and found abdominal pain in 46% of patients with DKA [11]. Adhikari et al., noticed vomiting and abdominal pain in 34.9% of patients, altered sensorium in 47%, kussmaul breathing in 28% and hypotension in 46% of patients with DKA [7].

DKA can be the initial presentation of diabetes mellitus or precipitated in known patients with diabetes mellitus by many factors, most commonly infection [12]. Other precipitating factors include acute myocardial infarction, any cerebrovascular accident or any postoperative stress. Adhikari et al., found infection as a precipitating factor for DKA in 58% of patients [7]. Studies of Vignati et al., emphasized the importance of infection as a precipitating cause occurring in up to 50% of patients [13]. Matoo et al., and Westphal found an incidence of infection in 30% and 40% of patients respectively [14,15]. Noncompliance is also one major precipitating factor for DKA. Matoo et al., found that incidence of non-compliance to treatment was 20% and while Westphal found it 16% [14,15]. Often more than factors may be present in a patient or rarely no obvious factor can be identified. A study conducted by Umpierrz et al., found no obvious factor of DKA in 2-10% of cases [16].

The management of diabetic ketoacidosis is complex and involves many aspects [17]. These include:

1. A careful clinical evaluation of the patient and identification of all the metabolic abnormalities and their correction.

2. Meanwhile all efforts should be made for identification of precipitating and co-morbid conditions and its treatment.

3. Once acute phase is over, a comprehensive approach should be made for appropriate long-term treatment of diabetes, and plans to prevent recurrence.

Another most important aspect of management is patient education so as to ensure compliance to treatment as non-compliance may lead to DKA in patients with DM [14,15].

DKA is the most common acute complication in children and adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes which leads to high mortality. It accounts for almost 50% mortality in diabetic patients younger than 24 years of age [18]. Though the overall mortality is rare in adults with DKA; a higher mortality rates occur in the elderly and in patients with co-morbidities [19,20]. Underlying precipitating illness is the major cause of death in these patients than hyperglycaemia or ketoacidosis [7,21].

This study was conducted to study the clinical profile of DKA patients. The mortality from DKA varies from 3-13%, therefore it is important to recognize DKA at an earlier stage as early recognition of DKA, leads to less complications and is associated with increased incidence of successful recovery.

Materials and Methods

Study design This study was a prospective study conducted in a Tertiary care Hospital taking a total of 60 patients of Type 1 and 2 Diabetes Mellitus admitted in the Emergency who were diagnosed to have DKA on the basis of following criteria:

Diagnostic Criteria for Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) [8]

• Blood glucose (mg/dl) > 250

• Arterial pH <7.3

• Serum bicarbonate (mEq/l) <15

• Moderate degree of ketonaemia and ketonuria (As determined by nitroprusside method)

Patients on steroids and other Endocrine disorders like Cushing’s syndrome, Acromegaly which can also cause Hyperglycaemia were excluded from the study.

The clinical profile, precipitating factors and clinical outcome was analysed.

Ethics:This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation of the institution.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done just by calculating percentages. No other statistical test was required in this study.

Results

Out of 60 patients, 12 (20%) patients belong to type 1 diabetes mellitus and 48 (80%) patients belong to Type 2 DM. Among them, 34 (56.66%) were males and 26 (43.33%) were females. The male: female ratio was 1.3:1. Our study showed that only 14 (23.3%) patients were on regular treatment while 32 patients (53.33%) were on irregular treatment and eight patients (13.33%) were not taking any treatment for Diabetes. In six (10%) patients Diabetic status was detected only when they presented with DKA complication. Age and sex distribution of the patients is stated in [Table/Fig-2].

Clinical presentation was analysed and it was found that nausea and vomiting were present in maximum number of patients (63.33%). Symptoms related to precipitating cause were also present in a large number of patients (60%). Pain abdomen was present in (43.33%) of patients, while altered sensorium and polyuria/ polydipsia were present in 30% and 26.66% of cases respectively. Twenty (33.33%) patients were dehydrated. Weakness was present in ten (16.66%) of patients. Kussmaul breathing was present in ten (16.66%) patients. Only eight (13.33%) patients had hypotension [Table/Fig-3].

The most common precipitating factor was found to be infection (73.33%), followed by non-compliance to treatment (66.66%), and followed by stressful conditions (26.66%). In six (10%) patients diabetic status was detected only when they presented with DKA complication and all the six patients belong to Type 1 DM [Table/Fig-4].

Since out of 60 patients of DKA, 44 (73.33%) patients had evidence of infection, types of infections were further analysed. Most common infection was found to be of pneumonia (18 patients, 40.90%). Four (9.09%) patients had sputum AFB positive pulmonary tuberculosis. Urinary tract infection was the precipitating cause of DKA in 12 patients (27.27%). Among them, two patients had emphysematous pyelonephritis. four patients (9.09%) had diabetic foot and two patients (4.54%) had gastrointestinal tract infection.

Four patients (9.09%) had mixed infection like two patients had pneumonia and urinary tract infection and the other two had diabetic foot and urinary tract infection [Table/Fig-5].

Mean blood glucose at admission was 535.6 mg/dl in Type 1 and 380.07 mg/dl in Type 2 DM patients. Mean serum potassium (4.55mEq/l), arterial pH (7.23) & bicarbonate level (12.46 mmol/l) were calculated. In our study severe acidosis with arterial pH <7.0 was found mainly in Type 1 Diabetic patients with DKA.

Mean fluid requirement on first day of therapy was 3.51 litres. Mean insulin dosage required for clearance of urinary ketones was 115 units while mean time taken for clearance of urinary ketones was 36.20 hours. However, 6 patients expired before clearance of urinary ketones.

Discussion

In our study, a total of 60 patients presenting to the emergency with diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis were taken, out of which 12 (20%) patients belong to Type 1 DM and 48 (80%) patients belong to Type 2 DM. It is because prevalence of Type 2 DM is much higher than Type 1 DM. Moreover, in a developing country like India, due to poor socio-economic status, many patients with type 2 DM tend to have poor compliance and poor control of blood sugar levels so any precipitating factor tends to land them in a state of DKA. National Centre for health statistics and study by Adhikari et al., also showed the same [2,7]. A recent study evaluating 138 consecutive admissions for DKA at a large academic center observed that 21.7% had type 2 diabetes [22]. In a study conducted in Taiwan, the patients attacked with DKA were predominant type 2 DM (98 vs. 39 patients) [23]. Nearly 70% of the admissions involved discontinuation of medications, and almost half had an identifiable infection when an intensive search was undertaken. S Mishra has reviewed the pathophysiology of ketosis prone type 2 diabetes in his recent article and shown that DKA is not just the feature restricted to Type 1 diabetes but can also be a complication of type 2 diabetes usually with a precipitating factor and in some races even without precipitating cause [5,24].

Mean age of patients in our study group was 51.46 years which also points in favour of type 2 diabetes to be causing DKA more than type 1 diabetes. Many studies support this finding. In the study by Adhikari et al., the mean age was 44.78 years [7]. Faich et al., and Kreisberg et al., studies reported that the mean age of patients admitted for DKA was between 40-50 years [25,26]. Beigelman et al., study reported 47 years as the mean age of presentation for DKA [27].

The percentage of freshly diagnosed diabetes has been variably reported. Our study result matches with Kretz AJ et al., which also found that 10% patients were freshly diagnosed [28]. Casteels and Mathieu found DKA was the presenting illness in 20-25% of newly diagnosed patients with type 1 diabetes [29]. Westphal found ketosis onset diabetes in 27% of patients [15].

Nausea and vomiting were the most common symptoms (63.33%) of DKA patients in our study, followed by pain abdomen (43.33%). One third (33.33%) of patients were dehydrated. Altered sensorium was seen in 30% of patients. 26.66% of patients were complaining of polyuria and polydipsia. Only 16.66% of patients had kussmaul breathing and 13.33% had hypotension. Symptoms related to precipitating cause were present in 60% of patients. A similar incidence of symptoms has been reported in previous studies by Munro et al., Umpierrez et al., and Adhikari et al., [7,10,11].

In our study many patients had more than one precipitating factor like patients who were non-compliant to treatment also had infection and associated stressful situations like acute myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, postoperative stress etc. Thus, it is seen that presence of non-compliance to treatment is an important precipitating factor which indicates that prevalence of DKA can be reduced by proper education of patients about their illness and harm of non-compliance. Welch et al., did a case study on patients with type 2 diabetes presenting with DKA and found that some precipitating factor is required in a type 2 diabetic patient to land up in DKA as similar to our study [4].

Present study showed pneumonia as the most common infection precipitating DKA in 40.90% of patients. Sputum AFB positive Pulmonary Tuberculosis was present in 9.09% patients. Urinary Tract Infection was the precipitating infection in 27.27% of cases, among them, one patient had Emphysematous Pyelonephritis. 9.09% patients had diabetic foot and gastrointestinal tract infection in 4.54% of patients. Mixed infection was the causative factor in 9.09% of patients. Several factors including hyperglycaemia, leucocyte dysfunction, macrovascular disease and acidosis predispose the diabetic with ketoacidosis to common and rare infections. This is in accordance with previous studies which also showed that infection of any site is an important precipitating factor in causing DKA [13-16]. Adhikari et al., showed diabetic foot as the infection precipitating DKA in 30.23% of patients [7].

The overall mortality in our study was 10% which is quite similar to other studies. Westphal found mortality of 5.1% [15], while Beigelman and Faich et al., found mortality rate of 9% [25,27]. Adhikari et al., found mortality of 16.3% and Matoo et al., study showed mortality of 23.7% [7,14]. Estimated mortality rate for DKA is between 4-10% showed by Chaisson et al., [30]. This shows that DKA in patients with type-2 DM is a more severe disease with worse outcomes compared with type-1 DM. A comparative study in patients presenting with DKA also showed that type 2 DM patients who present in DKA have significantly severe presentation and worse outcome than those who have Type 1 DM [31]. Indian studies still report mortality figures in the range of 20-30%, and hence, may constitute preventable mortality. Delayed presentation and poor socio-economic conditions which influenced the selection of better antibiotics were contributory. This study shows that the clinical profile of patients with diabetic ketoacidosis is similar to that reported from West and other Indian studies. Delay in hospitalization, severity of acidosis and peripheral vascular insufficiency appeared to be a major risk factor for the higher mortality rate.

Pathogenesis of DKA and HHS: stress, infection, or insufficient insulin

Age and sex distribution in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis

| Age range (years) | Male | Female | Total |

|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

|---|

| 20-40 | 12 | 20.00 | 10 | 16.66 | 22 | 36.66 |

| 41-60 | 12 | 20.00 | 8 | 13.33 | 20 | 33.33 |

| 61-80 | 10 | 16.66 | 8 | 13.33 | 18 | 30.00 |

| Total | 34 | 56.66 | 26 | 43.33 | 60 | 100 |

| Mean age (years) | 51.58 | 51.30 | 51.46 |

Symptomatology in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis

| Symptoms | Number of patients | Percentage |

|---|

| Nausea/vomiting | 38 | 63.33 |

| Pain abdomen | 26 | 43.33 |

| Weakness | 10 | 16.66 |

| Polyuria/polydipsia | 16 | 26.66 |

| Dehydration | 20 | 33.33 |

| Hypotension | 8 | 13.33 |

| Kussmaul breathing | 10 | 16.66 |

| Altered sensorium | 18 | 30.00 |

| Symptoms related to precipitating cause | 36 | 60.00 |

Precipitating factors of diabetic ketoacidosis

| Precipitating factors | No. of patients | Percentage |

|---|

| Infection | 44 | 73.33 |

| Non-compliance to treatment | 40 | 66.66 |

| Stressful condition | 16 | 26.66 |

| First presentation | 6 | 10.00 |

| Unknown | 4 | 6.66 |

Infections precipitating diabetic ketoacidosis

| Infections | Number of patients | Percentage |

|---|

| Pneumonia | 18 | 40.90 |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 4 | 9.09 |

| Urinary tract infection | 12 | 27.27 |

| Diabetic foot | 4 | 9.09 |

| Gastrointestinal tract infection | 2 | 4.54 |

| Mixed infection | 4 | 9.09 |

| Total | 44 | 100 |

Conclusion

An active measure should be taken stressfully to rule out DKA in any diabetic and comatose patient to prevent complications and mortality, as the mortality mainly depends on the general condition of the patient, as well as the coexistent medical illness and time of onset of therapy. Therefore, education of a diabetic patient about warning symptoms of ketosis such as weakness, abdominal pain, vomiting and drowsiness are mandatory for early diagnosis and treatment.

[1]. AE Kitabchi, G.E Umpierrez, Thirty years of personal experience in hyperglycaemic crises: Diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar stateClin Endocrinol Metab 2008 93(5):1541-52. [Google Scholar]

[2]. National Center for Health Statistics. National hospital discharge and ambulatory surgery data. [article online]. Available from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/hdasd/nhds.htm Accessed 24 January 2009 [Google Scholar]

[3]. S Kim, Burden of hospitalizations primarily due to uncontrolled diabetes: implications of inadequate primary health care in the United StatesDiabetes Care 2007 30:1281-82. [Google Scholar]

[4]. BJ Welch, I Zib, Case Study: Diabetes Ketoacidosis in Type 2 Diabetes: “Look Under the Sheets”Clinical Diabetes 2004 22(4):198-200.doi: 10.2337/diaclin.22.4.198 [Google Scholar]

[5]. S Misra, N Oliver, A Dornhorst, Diabetic ketoacidosis: not always due to type 1 diabetesBMJ 2013 346:f3501 [Google Scholar]

[6]. A Balasubramanyam, JW Zern, DJ Hyman, V Pavlik, New profiles of diabetic ketoacidosis: type 1 and type 2 diabetes and the effect of ethnicity.Arch Intern Med 1999 159:2317-22. [Google Scholar]

[7]. PM Adhikari, N Mohammed, P Pereira, Changing profile of diabetic ketosisJ Indian Med Assoc 1997 95(10):540-42. [Google Scholar]

[8]. CR Kahn, GC Weir, In: Joslin’s Diabetes Mellitus 1996 13th EditionPhiladelphiaLea and Febiger:489-507. [Google Scholar]

[9]. AE Kitabchi, GE Umpierrez, JM Miles, Hyperglycaemic Crises in Adult Patients with DiabetesDiabetes Care 2009 32(7):1335-43. [Google Scholar]

[10]. JF Munro, IW Campbell, AC Mc Cuish, LJ Duncan, Euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosisBr Med J 1973 2:578-80. [Google Scholar]

[11]. G Umpierrez, AX Freire, Abdominal pain in patients with hyperglycaemic crisesJ Crit Care 2002 17:63-67. [Google Scholar]

[12]. JF Wilson, Diabetic Ketoacidosis- The ClinicsAnn Int Med 2010 152(1):ITC1-1. [Google Scholar]

[13]. L Vignati, AC Asmal, WL Black, SJ Brink, JW Hare, Coma in diabetes. In: Marble A, Krall LP, Bradley RF, et al (eds). Joslin’s Diabetes Mellitus 1985 12th EditionPhiladelphiaLea and Febiger:526-48. [Google Scholar]

[14]. VK Matoo, K Nalini, RJ Dash, Clinical profile and treatment outcome of diabetic ketoacidosisJ Assoc Physicians India 1991 39:379-81. [Google Scholar]

[15]. SA Westphal, The occurrence of diabetic ketoacidosis in non-insulin dependent diabetes and newly diagnosed diabetic adults Am J Med 1996 101(1):19-24. [Google Scholar]

[16]. GE Umpierrez, M Khajavi, AE Kitabchi, Review: diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar nonketotic syndromeAm J Med Sci 1996 311:225-33. [Google Scholar]

[17]. OA Fasanmade, IA Odeniyi, AO Ogbera, Diabetes ketoacidosis: diagnosis and management: AfrJ Med Med Sci 2008 37(2):99-105. [Google Scholar]

[18]. J Wolfsdorf, N Glaser, MA Sperling, Diabetic ketoacidosis in infants, children, and adolescents: a consensus statement from the American Diabetes AssociationDiabetes Care 2006 29:1150–-2259. [Google Scholar]

[19]. ML Malone, V Gennis, JS Goodwin, Characteristics of diabetic ketoacidosis in older versus younger adultsJ Am Geriatr Soc 1992 40:1100-04. [Google Scholar]

[20]. GE Umpierrez, JP Kelly, JE Navarrete, MM Casals, AE Kitabchi, Hyperglycaemic crises in urban blacksArch Intern Med 1997 157:669-75. [Google Scholar]

[21]. A Kitabchi, G Umpierraz, M Murphy, Management of hyperglycaemic crises in patients with diabetesDiabetes Care 2001 24:131-53. [Google Scholar]

[22]. CA Newton, P Raskin, Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes: Clinical and Biochemical differences Arch Intern Med 2004 164(17):1925-31. [Google Scholar]

[23]. CH Chu, JK Lee, HC Lam, CC Lu, The Occurrence of Diabetic Ketoacidosis in Type 2 Diabetic Adultshttp://www.tsim.org.tw/journal/jour10-6/P10_230.PDF [Google Scholar]

[24]. GE Umpierrez, W Woo, WA Hagopian, SD Isaacs, JP Palmer, LK Gaur, Immunogenetic analysis suggests different pathogenesis for obese and lean African-Americans with diabetic ketoacidosisDiabetes Care 1999 22:1517-23. [Google Scholar]

[25]. GA Faich, HA Fishbein, SE Ellis, The epidemiology of diabetic acidosis: A population based studyAm J Epidemiol 1983 117:551-58. [Google Scholar]

[26]. R Kreisberg, Diabetic ketoacidosis. In: Rifkin H, Porte D (eds). Diabetes mellitus: Theory and practice 1990 4th EditionNew YorkElsevier Science:591-603. [Google Scholar]

[27]. PM Beigelman, Severe diabetic ketoacidosis (diabetic “coma”). 482 episodes in 257 patients; experience of three yearsDiabetes 1971 20:490-500. [Google Scholar]

[28]. JC Pickup, G Williams, Textbook of Diabetes 2003 3rd EditionMassachusetts, USABlackwell Science:32.1-33.19. [Google Scholar]

[29]. K Casteels, C Mathieu, Diabetic ketoacidosisRev Endocr Metabol Disord 2003 4:159-66. [Google Scholar]

[30]. JL Chiasson, NA Jilwan, R Belanger, Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis and the hyperglycaemic hyperosmolar stateCMAJ 2003 168(7):859-66. [Google Scholar]

[31]. L Barski, R Nevzorov, I Harman-Boehm, A Jotkowitz, E Rabaev, M Zektser, Comparison of diabetic ketoacidosis in patients with type-1 and type-2 diabetes mellitusAm J Med Sci 2013 345(4):326-30. [Google Scholar]