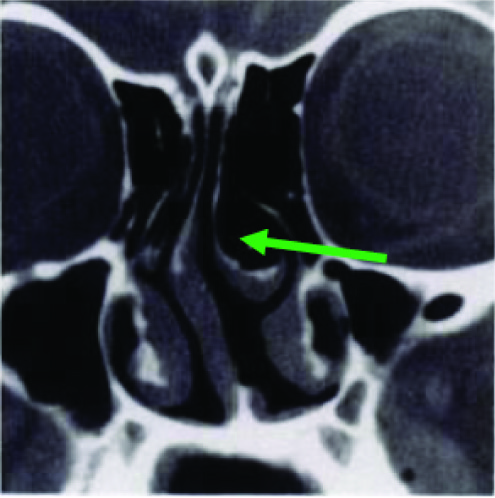

Chronic rhino sinusitis (CRS) is the most common disease for which consultation of otorhinolaryngologist is sought [1]. The approach to patients with chronic rhino sinusitis has changed after Messerklinger published the first comprehensive account of technique of nasal endoscopy and its application to the diagnosis and treatment of sinonasal diseases [2]. The endoscopic surgery aims at removing the obstruction of the main drainage pathway- in the osteomeatal complex-based essentially on the concept that such obstruction perpetuates the sinus disease. The key underlying concept behind minimally invasive functional endoscopic sinus surgery is the osteomeatal complex (OMC) – the small compartment located in the region between the middle turbinate and the lateral nasal wall in the middle meatus – represents the region for drainage of anterior ethmoid, maxillary and frontal sinuses [Table/Fig-1] [3,4]. Obstruction of OMC causes a vicious cycle of events that lead to sinusitis. Its obstruction leads to mucosal congestion that decreases air flow and leads to further obstruction [5].

Surgical clearance of these chronically infected sinuses while maintaining their ventilation and drainage is the treatment of choice [6]. To achieve this goal, there should be some diagnostic modalities which guide us towards exact diagnosis and safe intervention. Over the past few decades, both CT and nasal endoscopy have been used successfully as diagnostic modalities in sinus disease. The purpose of these investigations is to determine the mucosal abnormalities and bony anatomic variations of paranasal sinus and assess the possible pathogenicity of these findings in patients undergoing evaluation for sinusitis.

The revolutionary changes in the surgical treatment of rhino sinusitis in recent years, particularly in endoscopic surgery, require the surgeons to have detailed knowledge of the anatomy of the lateral nasal wall, paranasal sinuses and surrounding vital structures and of the large number of anatomical variants in the region, many of which are detectable only by the use of CT [7]. Presumably these variations might induce osteomeatal obstruction, preventing mucus drainage and predisposing to chronic rhino sinusitis.

Few studies of Indian origin have examined the putative role of anatomical variations of osteomeatal complex such as concha bullosa, septal deviation, uncinate process variations, agger nasi cells, haller cells and paradoxically curved middle turbinate in the development of traditional CRS [6]. We sought herein to examine the prevalence of these osteomeatal complex variations in the CRS cases through the use of computed tomography.

Materials and Methods

This present study titled “Study of anatomical variations of the osteomeatal complex in chronic rhino sinusitis patients” using computed tomography was conducted in the Department of ENT, BLDEU’S Shri B M Patil Medical College Hospital & Research Centre, Bijapur from November 2009 to October 2010.

Source of Data: All the patients attending the ENT outpatient department, who had chronic sinusitis for more than three months duration not responding to the medical line of treatment and who were willing to undergo Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery.

Sample Size: Using the statistical formula of N= 4pq/L2 and taking the prevalence of anatomical variations of osteomeatal complex in chronic sinusitis as 65% and 95% confidence intervals and allowable error as 20%, the worked out sample size was 54.

Sampling: Consecutive eligible cases.

Inclusion Criteria: All the consecutive patients undergoing FESS for chronic rhino sinusitis in BLDE University Shri B M Patil Medical College Hospital and Research Centre.

Exclusion Criteria: Polypoidal or other expansive lesions, patient’s with surgical or traumatic antecedents in nasosinusal region, facial disturbances, acute infections, fungal sinusitis , patients with altered ciliary motility like immotile cilia syndrome, kartageners syndrome, down syndrome and cystic fibrosis

Methods of Collection of Data

All the patients in active stage of the disease were treated with course of suitable antibiotic, systemic antihistamines and local decongestants.

Each patient underwent computed tomography of nose and para nasal sinuses.

Results and Observations

The present study was conducted in the Department of ENT, BLDEU’S Shri B M Patil Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Bijapur, India. The study subjects included consecutive 54 patients of chronic sinusitis during the period from November 2009 to December 2010; in whom we searched for anatomical variations by means of computed tomography images.

The age of the patients in our study varied from 13 to 70 y. 73% of the patients were relatively younger as they were either equal to or less than 40 y of age with equal proportion of the patients in the age groups of 21-30 y and 31-40 y.

Our study included 32 females and 22 males. Thus male to female ratio was 1: 1.45.

Anatomical Variations

In our study it was observed that 53.7% of the chronic sinusitis cases had 2 or more anatomical variations and 33.3% of the cases had single anatomical variation.

Deviated nasal septum was found to be the most common amongst the anatomical variations in chronic sinusitis cases in the present study which was followed by unilateral concha bullosa and paradoxically bent middle turbinate. Agger nasi cell and Haller cell were seen in one case each [Table/Fig-2].

Distribution of anatomical variations in study subjects

| Anatomical variations | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| Deviated nasal septum | 40 | 74.1 |

| Unilateral concha bullosa | 18 | 33.3 |

| Bilateral concha bullosa | 11 | 20.4 |

| Paradoxically bent middle turbinate | 8 | 14.8 |

| Uncinate hypertrophy | 3 | 5.6 |

| Uncinate deviation | 5 | 9.3 |

| Agger Nasi Cell | 1 | 1.9 |

| Haller Cell | 1 | 1.9 |

Discussion

The surgical management of CRS has evolved over the years. External facial incisions, extensive nasal packing and prolonged hospital stays have been replaced by minimally invasive surgery. This involves opening the obstructed ostia to provide normal ventilation with preservation of adjacent mucosa [8,9]. While excellent results have been reported in the literature to date [10,11], given the close relation of the paranasal sinuses to important structures such as the orbit and skull base, if complications occur in surgery, they are usually dangerous and harmful.

Anatomical variations in the sinonasal region are common. Recent advances in CT scanning and the widespread of ESS, as well as the presence of universal agreement in the variation nomenclature and terminology has made the extent of these variations apparent. Local anatomic variations including concha bullosa, deviated nasal septum (DNS), Haller cells, paradoxical middle turbinates, agger nasi cells and many others may be the source of middle meatal obstruction and subsequent rhino sinusitis.

In our study we found anatomical variation in osteomeatal complex of 87% chronic rhino sinusitis patients, out of which 53.7% had two or more anatomical variations and the remaining 33.3% had single anatomical variation. Similar findings were reported by Liu X et al., who observed prevalence of about 81% anatomical variations in chronic rhinosinuistis cases [12]. Severino Aires de Araujo Neto et al., reported relatively less anatomical variations 65% in the osteomeatal complex of the chronic rhino sinusitis cases [13]. Perez et al., also observed similar prevalence of anatomical variations in the chronic sinusitis cases [14].

Nasal Septal Deviation

Nasal septum is fundamental in the development of the nose and paranasal sinuses. It is the epiphyseal platform for the development of the facial skeleton [15]. 74.1% of the patients in our study presented with nasal septal deviation [Table/Fig-2]. Deviated nasal septum causes a decrease in the critical area of the osteomeatal unit predisposing to obstruction and related complications. Similar finding were observed by Perez et al., who reported the prevalence of deviated nasal septum to be about 80% [14]. Infact in various studies the finding of nasal septal deviation ranged from 14.1% to 80%, Dutra and Marchiore et al., [16]14.1%, Arslan et al., [17] 36%, Earwaker et al., [18] 44%. Dua et al., and Asruddin et al., found prevalence of 44% and 38% of deviated nasal septum in their respective studies [6,19]. Stallmann et al., and Mamtha et al., also reported lesser prevalence of 60% and 65% deviated nasal septum in chronic rhino sinusitis cases respectively [20,21].

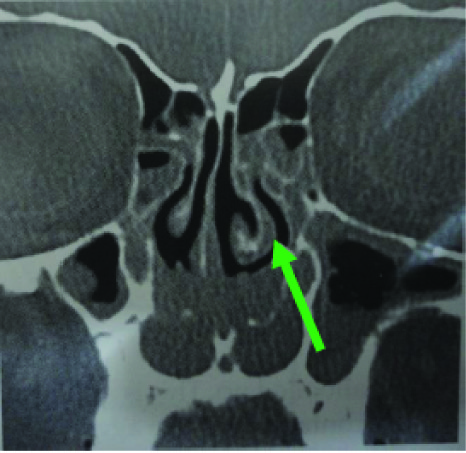

Concha Bullosa

Concha bullosa (pneumatised middle turbinate)[Table/Fig-3] has been implicated as a possible aetiological factor in the causation of recurrent chronic sinusitis. It is due to its negative influence on paranasal sinus ventilation and mucociliary clearance in the middle meatus region as quoted by Tonai [22]. Concha bullosa was seen in 53.7% of the chronic rhinosinuistis cases (unilateral 33.3%, bilateral 20.4%) which is almost similar to as reported by Bolger et al.,[7] and Yousem et al., [23] respectively. Perez-Pinas et al., and Scribano et al., reported higher prevalence of concha bullosa i.e. 73% and 67% in chronic rhino sinusitis cases [14,24]. The prevalence of concha bullosa in our study is on the higher side when compared to the findings of Stallmann et al., [20], Maru et al., [25] and Alkire BC et al., [26] who reported it to be 44%, 42.6% and 41.7% respectively.

Bilateral concha bullosa with septal deviation to right side (Arrow)

Wani et al., Dua et al., Asruddin et al., Mamtha et al., Zinreich et al., Llyod et al., and Weinberger et al reported further less prevalence of about 36%, 30%, 28%, 16% ,15%, 14% and 15% respectively [1,6,19,21,27–29].

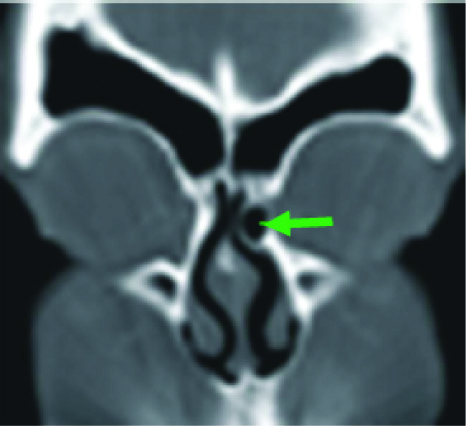

Paradoxically Curved Middle Turbinate

The middle turbinate may be paradoxically curved i.e. bent in the reverse direction [Table/Fig-4]. This may lead to impingement of the middle meatus and thus to sinusitis. Stammberger and Wolf [30] accepted paradoxical curvature of the middle turbinate as an etiological factor for CRS because it may cause obliteration or alteration in nasal air flow dynamics. It was found in 14.8% of the patients; the prevalence is similar to that of 12% by Asruddin et al., [19] and 15% by Llyod [28]. It is less than that reported by Bolger et al., 27% and Al-Qudah et al., 18% respectively [7,31]. Lesser prevalence of paradoxically middle turbinate was observed by Wani et al., [1].

Paradoxically curved middle turbinate (Arrow)

Uncinate Process of the Ethmoid Bone

We observed that the uncinate process may be deviated or pneumatized. Uncinate deviation can impair sinus ventilation especially in the anterior ethmoid, frontal recess and infundibulum regions. The deviated uncinate was found in 9.3% of cases which is similar to the findings of the study by Maru et al., [25] but higher than that reported by Bolger et al., [7] 2.5%, Dua et al., [6] 6% and Asruddin et al., [19] 2% Llyod et al., [28] reported the prevalence of about 16% of deviation of the uncinate process in chronic rhino sinusitis cases and even 65 % prevalence of uncinate process deviation was seen in the study by Mamtha et al., [21].

Hypertrophied uncinate process causes narrowing of the hiatus semilunaris and the ethmoid infundibulum. It has also been suggested as a predisposing factor for impaired ventilation of the anterior group of sinuses and frontal sinus. Hypertrophy of the uncinate process was observed in 5.6% of the cases which is very less as compared to the findings of Wani et al., who reported it to be 21% in chronic rhino sinusitis cases [1].

Agger NASI Cell

Agger nasi cells [Table/Fig-5] lie just anterior to the anterosuperior attachment of the middle turbinate and frontal recess. These can invade the lacrimal bone or the ascending process of maxilla. These cells were the least observed in our study i.e. about 1.9% Similar results were observed by Liu X et al., [12] and Llyod et al., [28] who reported the prevalence of agger nasi cell as 0.7% and 3% in chronic rhinosinuistis cases whereas in the study by Dua et al., [6] agger nasi cells were found to be present in 20 patients (40%). The prevalence is very less as compared to 98.5% by Bolger [7], 88.5% by Maru [25], 86.7% by Tonai and Baba [32] and 48% by Asruddin [19].

Agger nasi cell(Arrow Mark)

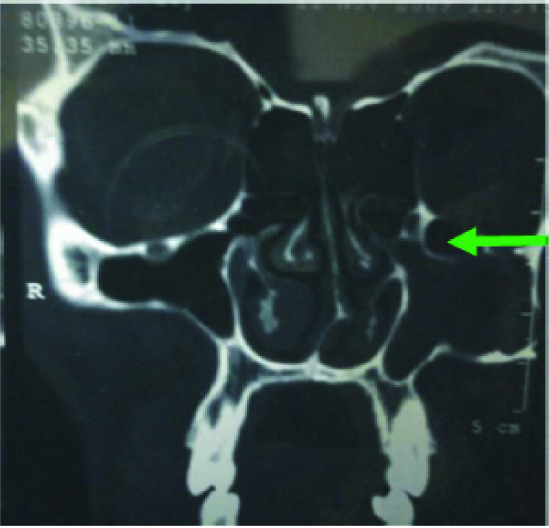

Haller’s Cell

Zinreich et al.,[33] and Kennedy et al., [34] described Haller’s cells as ethmoid air cells found inferior to the ethmoid bulla adhering to the roof of the maxillary sinus, in continuity with the proximal infundibulum, which formed part of the lateral wall of the infundibulum [Table/ Fig-6]. They are considered as ethmoid cells that grow into the floor of orbit and may narrow the adjacent ostium of the maxillary sinus especially if they become infected [35]. Davis et al., [36] noted the haller cell is thought to cause chronic sinusitis cases by impinging on the ostium of the maxillary sinus and infundibulum by inhibiting the ciliary function, leading to obstruction of the ostium.

Paradoxically bent middle turbinate & Haller cell (Arrow Mark)

The prevalence of Haller’s cells in our study was equal to that of agger nasi cell i.e. 1.9%. Similar findings were observed by Liu X et al., [12] who reported the prevalence of about 1 % of Haller cells in 297 chronic rhino sinusitis cases in a study conducted in Sun Yat Sen University of Medical Sciences. This is again very less as compared to that reported by Kayalioglu et al., [37] 5.5 %, Dua et al., [6] 16%, Llyod et al., [35] 15%, Perez-Pinas et al., [14] 20%, Tonai and Baba [32] 36%, Bolger et al., [7] 45.9%, Maru et al., [25] 36%, Alkire BC et al., [26] 39.9% and Asruddin et al., [19] 28% respectively.

Conclusion

In light of the results obtained in our study, it can be concluded that: Anatomical variations are common in the osteomeatal complex. Prevalence of multiple anatomical variations was more in our study in comparison to single anatomical variation. Deviated nasal septum was the most common anatomical variation encountered in our study followed by concha bullosa and paradoxically bent middle turbinate.

CT scan must be done prior to any functional endoscopic sinus surgery. They help in assessing the extent of sinus disease and to know the anatomical variations. Awareness of the possibility of such variations helps in making surgical decisions.