Introduction

Aesthetics plays an important role in modern society. People have come to understand the contribution of well aligned teeth, to beauty of face. Gone are the days when people feared knife to modify god’s creation. Osteotomies in association with orthodontics are efficient means to correct skeletal protrusion.

Facial harmony and balance are determined by the facial skeleton and its soft tissue drape. The architecture and topographic relationships of the facial skeleton form a “foundation” on which the aesthetics of the face is based. However, it is the structure of the overlying soft tissues and their relative proportions that provide the visual impact of the face.

Osteotomies of the facial skeleton can alter the form and function of facial structures. Alteration in face after these surgical procedures is not only confined to hard tissues. A degree of soft tissue alteration was noted for each bony movement.

There have been many reports in the literature of soft and hard tissue changes after orthognathic surgery but very few about anterior segmental surgery of maxilla and mandible [1]. Segmental maxillary surgery was performed for many years before total maxillary osteotomy became popular. Anterior maxillary osteotomy allows for improvement of occlusion, but often at the expense of facial aesthetics. The procedure is predictable from the standpoint of dental stability and soft tissue changes [2].

First reported anterior maxillary segmental osteotomy was performed in 1921 by Cohn-Stock. The procedure has since been modified with variation in incision design depending on the desired osseous movement [2]. Single stage set-back osteotomy through a vestibular approach was first described by Wassmund. Wunderer presented an important improvement of Wassmund’s technique in that he recommended a predominantly palatal approach, which simplified the procedure. Bell introduced the concept of ‘downfracturing’ in which the anterior segment is approached through a horizontal vestibular incision [3].

First description of an anterior subapical mandibular osteotomy was by Hullihen in 1849. Hofer made this procedure popular by recommending its use for dentoalveolar set-back as well as advancement. Kole advocated this osteotomy to treat anterior skeletal open bite by interposition of a bone graft taken from the lower border of the mandibular symphysis [3].

Modifications in the design of soft tissue incision and bony osteotomy have been made by many surgeons such as Wassmund, Wunderer and Bell. However many problems remained such as necrosis of the repositioned segment and devitalization of teeth, especially canines. Modified anterior segmental osteotomy was developed and reported at the European craniomaxillofacial surgeon’s congress in Zurich in 1996. Horizontal vestibular incision is given from canine to canine. A vertical bone cut is performed on the extraction space. The bicortical horizontal osteotomy between the canine root tip and the aperture piriformis is then carried out to connect the vertical osteotomies on the right and left sides. Mini plates are used to secure the position of anterior segment. In our study we have followed Modified anterior segmental osteotomy.

Anterior segmental osteotomy is indicated in excess vertical and or anteroposterior dimension of maxilla, bimaxillary protrusion, anterior open bite, in extreme reverse curve of spee and in asymmetry [2].

In our study we evaluated changes after surgery. The unintended facial changes were evaluated using cepahalometric and photometric analysis [Table/Fig-1,Table/Fig-2] . One of the salient finding of this study was the variability of soft tissue response to hard tissue movement. Variation in individual skeletal patterns and consequent variation in orthodontic, surgical and suturing procedures may account for some of this variability. The tonicity of the facial musculature can vary with skeletal patterns and influence the integumental response to dental and skeletal changes.

Materials and Methods

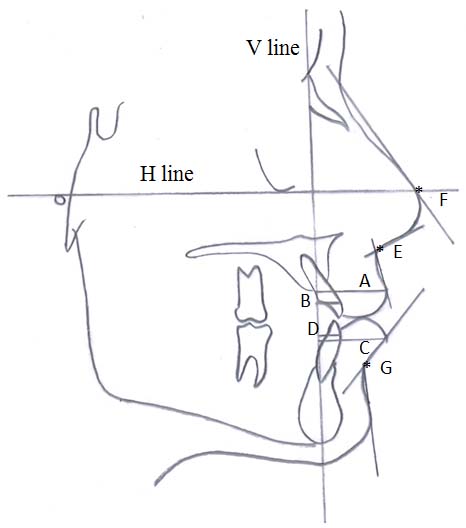

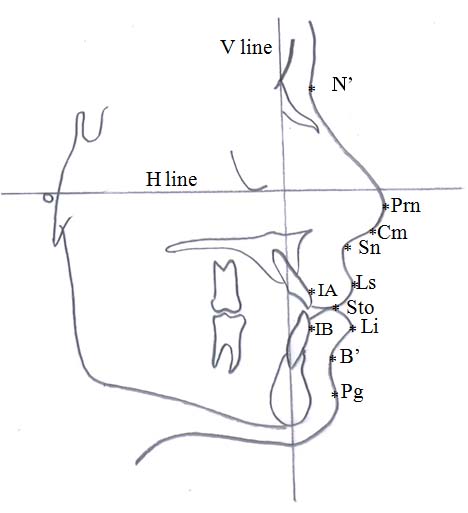

Ten patients aged 18-30 years who underwent anterior segmental osteotomy in Krishnadevaraya College of dental sciences, Bangalore, India were included in the study. Patients who underwent other orthognathic surgery and who were less than 18y or more than 50y were excluded in the study. All ten patients underwent preoperative and postoperative orthodontic treatment. Preoperative orthodontic treatment carries out decompensation of the compensation that is occurred due to skeletal deformity, align upper and lower teeth and co-ordinate upper and lower arch. In postoperative orthodontic treatment residual space distal tocanine is closed, minor leveling and alignment is done to correct the occlusion. Preoperative and postoperative records consisted of lateral cephalogram and frontal and lateral photographs. Lateral cephalograms were analysed using Cephalometrics for orthognathic surgery (COGS).COGS system describes horizontal and vertical portion of the facial bones by use of constant versatile system. Preoperative cephalometric measurements were taken before starting orthodontic treatment. Postoperative measurements were taken six months after surgery. Preoperative and postoperative measurements were carried out by the author. Reference plane constructed were FH – plane [H line] and nasion vertical plane (V line), which were perpendicular to FH – plane. Following landmarks were used [Table/Fig-3].

Soft tissue landmarks

Soft tissue nasion (N’) – Deepest point on the concavity overlying the area of frontonasal suture.

Pronasale (Prn) – The most prominent point on the nose tip.

Columella point (Cm) – The most anterior point on columella of nose.

Subnasale (Sn) –A point located at the junction between the lower border of nose and beginning of upper lip at mid-sagittal plane.

Labrale superius (Ls) – Most prominent point on the vermillion border of upper lip in the mid-sagittal plane.

Stomion (Sto) –Imaginary point at crossing of vertical facial midline and horizontal labial fissure between gently closed lips, with teeth in natural position.

Labrale inferius (Li) – Most prominent point on vermillion border of lower lip in the mid-sagittal plane.

Soft tissue point ‘B’ (B’) – The point at the deepest concavity between the Labraleinferius and soft tissue pogonion.

Soft tissue pogonion (Pg) – Most prominent or Anterior point on the soft tissue chin in mid-sagittal plane.

Hard tissue landmarks

Incision anterius (IA) – The most prominent point on maxillaryincisor as determined by a tangent to the incisor passing through subspinale.

Incision anterius (IB) – The most prominent point on the mandibular incisor as determined by a tangent to the incisor passing through supramentale.

In lateral aspect 4 linear and 3 angular measurements were evaluated [Table/Fig-4].

1. Upper lip protrusion: Ls to V line

2. Upper incisor protrusion: LA to V line

3. Lower lip protrusion: Li to V line

4. Lower incisor protrusion: IB to V line

5. Nasolabial angle: Cm-Sn-Ls

6. Nasal tip inclination: N-Prn to H line

7. Labiomental angle: Li-B-Pg

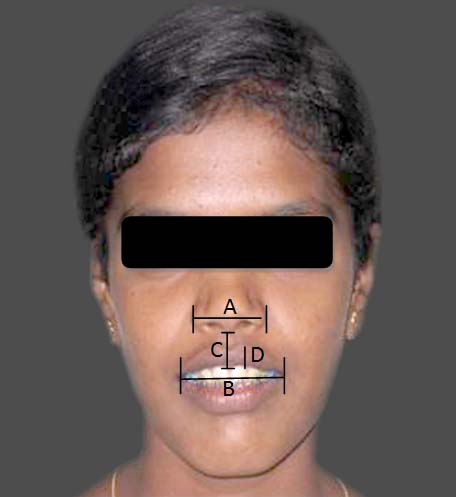

In frontal aspect 4 linear measurements were evaluated [Table/Fig-5].

1. Nasal width: alar to alar

2. Lip width: commissure to commissure

3. Philtrum length: subnasale to stomion

4. Vermillion length: top of cuspid bow to stomion

Results

Preoperative and postoperative changes were calculated by subtracting the corresponding values for each patient. Descriptive statistical analysis has been carried out in the present study. Results on continuous measurements are presented on Mean +SD (Min- Max) and results on categorical measurements are presented in Number (%). Significance is assessed at 5 % level of significance. Student t-test (two tailed, dependent) has been used to find the significance of study parameters on continuous scale within ach group. Wilcoxon signed rank test has been used to find the significance of parameters on non-parametric scale between Preop and post-op variables. Effect size is performed to find the effectof intervention.

Statistical analysis showed changes in both soft and hard tissue parameters [Table/Fig-6,7]. Changes were not uniform for all the parameters. Few parameters had significant changes where as others had suggestive significance or moderate significance.

Upper lip and upper incisor protrusion decreased postoperatively suggesting that anterior segmental osteotomy is effective when protrusion cannot be corrected by orthodontic treatment alone. Lower lip and lower incisor protrusion decreased but the changes were not statistically as significant as upper lip and upper incisor changes.

Nasolabial angle increased postoperatively suggesting that the surgery has positive effect on nasolabial relation. Nasal tip inclination and mentolabial angle increased postoperatively but changes were not statistically significant. Nasal width and philtrum length significantly increased postoperatively. Lip width and lip thickness decreased postoperatively.

Discussion

Various studies have been carried out to evaluate the postoperative changes. Mild alteration in the surgical techniques yields aesthetically pleasing results. To control the soft tissue changes associated with maxillary surgery, the surgeon must be aware of any pre-existing deformity, the anticipated soft tissue adaptation to the surgical procedure being planned, and the importance of the effects of orofacial muscles in form, function, and aesthetics[4].

Betts and colleagues, studied the soft tissue response to maxillary surgery and noted that soft tissue changes may be more affected by the type and position of the soft tissue incision and methods used in closure than by the surgically induced hard tissue changes [5]. For example, the horizontal incision in the upper labial vestibule commonly used to gain access to the maxilla causes shortening of the lip with loss of vermilion and a decrease in lip thickness, whereasvertical incisions with a tunneling approach and palatal flap for the same surgical procedure show minimal postoperative lip changes [6].

The importance of muscle repositioning following superior repositioning of the maxilla was stressed by many investigators [7-9]. They state that the muscles detached during stripping of the periosteum required for maxillary surgery shorten and retract laterally. The muscles reattach in this position if they are not reapproximated at the time of surgery. The lateral movement of the muscles and subcutaneous tissues causes the alar base to flare and the upper lip to thin. The loss of visible vermilion may be a result of other causes. These include a rolling under vermilion of the upper lip secondary to an incision made high in the vestibule with associated scarring and retraction and inclusion of large amounts of tissue during closure. This loss of vermilion is especially unattractive in those individuals with thin lips [4].

The upper lip closely follows the movement of the maxillary incisor in the horizontal plane. The lip follows approximately 40% of the vertical maxillary change. This lip shortening is accentuated with combined anterior and superior maxillary movements. The amount of vertical soft tissue change increases progressively from the nasal tip to Stomion superius, with loss of vermilion [4].

The soft tissue changes associated with the maxillary segmental setback osteotomy include an increase in the nasolabial angle because of posterior lip rotation around subnasale, lengthening of the upper lip, decrease in interlabial gap, uncurling and retraction of the lower lip, prominent nasal tip projection, increase in nasal width [8,10,11], decrease in lip width [8,10,11] and lip thickness [6,8,10,11].

One of the important concerns of oral surgeon and orthodontist should be preoperative distance between Labralesuperius and stomion. In past this was the most overlooked measurements, yet most talked by patients postoperatively. Decrease in lip length was initially thought to be due to intrusion of anterior segment of maxilla. For a given amount of maxillary intrusion, stomion moves farther superiorly than Labralesuperius, the distance between these two points would decrease, resulting in vertical upper lip thinning. This response was not only due to vertical movement but also due to horizontal movement [12].

While significant advances in the stability and predictability of maxillary surgery have been made over the years, minimal attention has been focused on the influence of maxillary surgery on the nose and facial soft tissues. Tissue dissection and horizontal bone cutting performed from the inferior aspect of the aperture performis minimize unfavorable nasal changes [1]. Maxillary setback procedures result in loss of nasal tip support because of posterior movement of the anterior nasal spine and the bony support area around the piriform aperture [4]. Several surgical techniques have been suggested which help to control the detrimental soft tissue changes associated with maxillary surgery. Changes in facial aesthetics and occlusion following orthognathic surgery depend highly on the stability achieved following surgery [4].

In our study we have used following techniques to achieve aesthetically pleasing results. The alar cinch sutures marginally increase postoperative nasal width resulting in acceptable postoperative nasal width. Contouring of the anterior nasal spine supports the columella and Septoplasty prevents postoperative buckling of nasal septum. We noticed that adequate elevation of periosteum and replacement of muscle attachment resulted in minimal postoperative oedema and acceptable postoperative changes.

Various authors have evaluated soft and hard tissue changes after anterior segmental osteotomy and have concluded that highest correlation coefficient was obtained between the soft and hard tissue changes in the upper lip region [13,14] and minimal changes in nasal and genial landmarks [15]. Reduction of labial prominence with an increase in nasolabial angle and philtrum length [15,16], upper incisor and vermillion length decreases [16].

Rajan Gunasheelan et al., did a retrospective study in 103 patients to evaluate intraoperative and postoperative complication in anterior segmental osteotomy and concluded that 30% of the patients in 103 series had complications attributed to different causes. Most commonly observed were soft tissue injuries (43.4%), dental complication (36.6%) and other complication attributed for 20%. Mechanical and technical complications depend to a great extent on the technique employed. Anterior segmental osteotomy is safe and reliable in hands of skilled surgeon [17].

Measurement differences of cephalometric analyses

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 |

| Upper lip protrusion | 6mm | 10mm | 5mm | 2mm | 4mm | 6mm | -2mm | 5mm | 2mm | 5mm |

| Upper incisor protrusion | 13mm | 13mm | 3mm | 8mm | 7mm | 8mm | 15mm | 7mm | 6mm | 10.5mm |

| Lower lip protrusion | 0mm | 16mm | 3mm | 4mm | 4mm | 3mm | -20mm | 4mm | 0mm | 3mm |

| Lower incisor protrusion | 1mm | 2mm | -1mm | 2mm | 3mm | 1mm | -1mm | 3mm | 1mm | 6mm |

| Nasolabial angle | -21deg | -6deg | -3deg | -25deg | -1deg | -8deg | -17deg | -1deg | -21deg | -1deg |

| Nasal tip inclination | 1deg | -4deg | 10deg | -1deg | 5deg | -7deg | -64deg | 6deg | -4deg | -4deg |

| Mentolabial angle | -4deg | 8deg | -3deg | -23deg | 18deg | 0deg | 20deg | 7deg | -3deg | 0deg |

Measurement differences of photometric analyses

| P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 | P10 |

| Nasal width [%] | -3mm | -2mm | -4mm | -2mm | -4mm | -4mm | -3mm | -3mm | -4mm | -2mm |

| Lip width [%] | 4mm | 5mm | 4mm | 6mm | 6mm | 3mm | 7mm | 2mm | 5mm | 7mm |

| Philtrum length [%] | 0mm | -1mm | -2mm | -2mm | -2mm | -3mm | -3mm | -3mm | -2mm | 0mm |

| Lip thickness [%] | 2mm | 0mm | 1mm | 1mm | 2mm | 0mm | 0mm | 1mm | 1mm | 2mm |

Four linear and three angular measurements in lateral aspect

Postoperative frontal photograph

Summary of soft tissue changes in lateral aspect

| Variables | Preoperative | Postoperative | Delta | p-value | Effect Size |

| Upper lip protrusion(mm) | 21.55±6.53 | 17.25±4.69 | 4.30±3.16 | 0.002** | 1.36(VL) |

| Upper incisor protrusion(mm) | 15.15±5.17 | 7.10±4.09 | 8.05±3.27 | <0.001** | 2.46(VL) |

| Lower lip protrusion(mm) | 15.10±7.2 | 12.30±5.91 | 2.80±3.74 | 0.042* | 0.75(M) |

| Lower incisor protrusion(mm) | 6.50±3.17 | 4.80±2.74 | 1.70±2.06 | 0.028* | 0.83(L) |

| Nasolabial angle(deg) | 93.40±22.71 | 101.30±21.5 | -7.90±10.85 | 0.032* | 0.73(M) |

| Nasal tipinclination(deg) | 60.60±11.1 | 66.80±23.77 | -6.20±21.01 | 0.683 | 0.3(S) |

| Mentolabial angle(deg) | 96.25±23.9 | 94.20±16.92 | 2.05±12.28 | 0.594 | 0.17(N) |

Summary of soft tissue changes in frontal aspect

| Variables | Preoperative | Postoperative | Delta | p-value | Effect Size |

| Nasal width [%](mm) | 21.30±3.97 | 24.40±4.2 | -3.10±0.99 | <0.001** | 3.12(VL) |

| Lip width [%](mm) | 32.80±2.35 | 28.10±2.77 | 4.70±1.49 | <0.001** | 3.15(VL) |

| Philtrum length [%](mm) | 16.70±1.77 | 18.50±2.46 | -1.80±1.14 | 0.001** | 1.59(VL) |

| Lip thickness [%](mm) | 6.10±0.88 | 5.10±0.74 | 1.00±0.82 | 0.004** | 1.22(VL) |

d<0.20

No effect (N) d<0.20

Small effect (S) 0.20 <d<0.50

Moderate effect (M) 0.50 <d<0.80

Large effect (L) 0.80<d<1.20

Very large effect (VL) d>1.20

+ Suggestive significance (p-value: 0.05 < p <0.10)

* Moderately significant ( p-value:0.01< p < 0.05)

** Strongly significant (p-value : p<0.01)

Conclusion

Anterior segmental osteotomy allows for improvement of occlusion and facial aesthetics which cannot be achieved by orthodontic treatment alone. Versatility and reliability of the procedure helps correcting various dentoalveolar defects. Complications associated with the procedure are rare.

d<0.20No effect (N) d<0.20Small effect (S) 0.20 <d<0.50Moderate effect (M) 0.50 <d<0.80Large effect (L) 0.80<d<1.20Very large effect (VL) d>1.20+ Suggestive significance (p-value: 0.05 < p <0.10)* Moderately significant ( p-value:0.01< p < 0.05)** Strongly significant (p-value : p<0.01)

[1]. Je Ukpark, Hwang Young Sook , Evaluation of soft and hard tissue changes after anterior segmental osteotomy on the maxilla and mandible.JOMFS 2008 66:98-103. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Fonseca Raymond J., 2:249Section 3, Chapter 11 [Google Scholar]

[3]. Langdon John D, Patel Golan F, Operative maxillofacial surgery,J Oral Med:477-483.Part 11, Chapter 39 [Google Scholar]

[4]. Peterson’s principles of oral and maxillofacial surgery.22nd Edition:1223-1234.Part 8, Chapter 59 [Google Scholar]

[5]. NJ Betts, R Fonseca, P Vig, Changes in nasal and labial soft tissues after surgical repositioning of maxilla.Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognathic Surg. 1993 8:7-23. [Google Scholar]

[6]. DJ Tomlak, J Pieuch, S Weinstein, Morphologic analysis of upper lip area fallowing maxillary osteotomy via tunneling approach.AM J Orthod. 1984 85:488-93. [Google Scholar]

[7]. L Wolford, lip-nasal aesthetics fallowing lefort 1 osteotomy.Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988 81:180 [Google Scholar]

[8]. SA Schendel, J Delaire, Facial muscles for, function and reconstruction in dentofacial deformities. In: Bell WH, White RP, editors.Surgical correction of dentofacial deformities. 1980 PhiladelphiaWB Saunders:259-80. [Google Scholar]

[9]. SA Shendel, LW Williamson, Muscle reorientation fallowing superior repositioning of maxilla.JOMFS 1983 41:235-40. [Google Scholar]

[10]. F O’Ryan, S Schendel, Nasal anatomy and maxillary surgery. 1. Esthetic and anatomic principles.Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognathic surgery. 1989 4:27-37. [Google Scholar]

[11]. F O’Ryan, S Schendel, Nasal anatomy and maxillary surgery. 2. Unfavorable nasolabial aesthetics fallowing lefort 1 osteotomy.Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognathic surgery. 1989 4:75-84. [Google Scholar]

[12]. Radney Larry J., Jacobs Joe D., Soft tissue changes associated with surgical total maxillary intrusion. Am J Orthod. 1981 :191-212. [Google Scholar]

[13]. M Okudaira, T Kawamoto, T Ono, T Moriyama, Soft tissue changes in association with anterior maxillary osteotomy: a pilot study.Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008 12(3):131-38. [Google Scholar]

[14]. MM Shawky, TI EI-Ghareeb, Abu Hameed, LA Hummos, Evaluation of the three dimensional soft tissue changes after anterior segmental maxillary osteotomy.Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012 41(6):718-26. [Google Scholar]

[15]. Jayaratne YSN, wahlen RAZ, Cheung JLOLK, Facial soft tissue response to anterior segmental osteotomies. a systematic review.Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg.. 2010 39:1050-58. [Google Scholar]

[16]. ZX WU, Subapical anterior maxillary osteotomy. A modified surgical approach to treat maxillary protrusion.J Cranio Surg. 2010 21(1):97-100. [Google Scholar]

[17]. Gunasheelan Rajan, IIanterior maxillary osteotomy. A retrospective evaluation of 103 patients. J oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009 67:1269-73. [Google Scholar]