Anxiety disorders that affect approximately one in four people at some point in their lives can impact on general functioning specifically psychological functioning, interpersonal functioning and educational/occupational functioning [1,2]. Individuals with anxiety disorders also experience impairment in interpersonal relationships, including marital functioning [3]. Quality of life describes an ultimately subjective evaluation of life in general that encompasses not only the subjective sense of well-being but also the objective indicators such as health status and external life situations [4]. High marital quality is associated with good adjustment, adequate communication, a high level of marital happiness, integration and a high degree of satisfaction with the relationship [5]. This study aimed to determine if Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) improves the quality of life of participants with anxiety disorders and if marital adjustment of participants with anxiety disorders and their spouses can be further improved with Behavioural Marital Therapy (BMT), relative to standard care that involves pharmacotherapy and psychoeducation. The specific hypotheses were that, compared to a group of persons with anxiety disorders that received pharmacotherapy and psychoeducation (the standard care or control group), the CBT and BMT group will a) report significantly better quality of life and b) significantly better marital adjustment.

Methods

The study protocol, that utilized an open label randomised clinical trial design, was approved by the departmental research committee and adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained prior to enrolling participants in the study. The inclusion criteria for participation in the study were a) age between 20 and 55 years, b) able to comprehend the local vernacular language and/or English, c) minimum education of 7th grade, d) married couples with at least one spouse diagnosed with anxiety disorders based on the WHO ICD-10 classification (F40- F42), and marital discord (a score >80 on the marital quality scale), e) both participant and the spouse provided informed consent to participate in the trial. The exclusion criteria included a) participants and spouses having any major co-existing physical illness, mental retardation, severe psychotic illness, severe disabling medical illness or substance abuse or severe depression (severe depression was identified using the Beck Depression Inventory) and b) participants had prior individual or marital therapy. Participants were recruited from two private psychiatry practices and data were collected from participants at regularly scheduled intervals.

Based on a preliminary pilot study, we assumed a mean baseline quality of life score in the psychological domain of 55 and that CBT will improve the mean score of the psychological domain to as much as 70 (a higher score indicates better quality of life). The sample size was estimated using a two sample comparison of means procedure and with the commercially available STATA version 10 (College Station, Tx, USA) statistical software package. With power set at 0.8, a two sided alpha of 0.05, and two groups, the sample size was estimated at 23 participants in each group. With power set at 0.9, a two sided alpha of 0.05, and two groups, the sample size was estimated at 30 participants in each group. For marital adjustment, the sample size was estimated at 29 participants in each group with a power of 0.8, a two sided alpha of 0.05, and two groups with the proportion of participants who may improve as 25% in the control group and 70% in the therapy group. The sample size for this study was thus determined as 30 participants in each arm and a minimum of 23 participants in each arm.

Eligible, enrolled participants were allocated to the intervention arms using a predetermined randomisation schedule that had blocks of unequal length. The randomization schedule for each participant was placed in a sealed opaque envelope that was opened by an independent observer not related to the study after the investigator administered the study instruments at baseline. Self-reported socio-demographic information included the age, gender, occupation, years of marriage, reported family income, the type of family and number of family members. Clinical details including the diagnosis, age at onset of illness, duration of illness, major complaints, details of treatment and complications and current clinical status were extracted from the medical records.

The WHOQOL-Bref instrument [6], a 26 item abbreviated version of the WHO Quality of Life- 100 item scale that includes one item from each of the 24 facets contained in the WHOQOL-100, was used to measure the quality of life of participants and their spouses at baseline and repeated 14 weeks after baseline assessment. This instrument measures the subjective evaluation of life in four domains of a) physical health, b) psychological health, c) social relationships and d) environmental domains. In addition, two items from the Overall quality of Life and General Health facet were included. Each item is rated on a five point scale. Higher scores indicate a better quality of life. Raw domain scores are calculated by straightforward summative scaling of constituent items and are transformed to a 0-100 scale.

Marital adjustment was measured using a marital quality scale developed in India [7]. There are 12 factors in the marital quality scale: understanding, rejection, satisfaction, affection, despair, decision making, discontent, dissolution potential, dominance, self-disclosure, trust and role functioning. The scale has an internal consistency (cronbach’s alpha coefficient=0.91) and high re-test reliability (r=0.83, over a 6 weeks interval). The scale has 50 items in statement form with four point rating scale and is administered separately for males and females. A score of above 80 for the patient and /or the spouse suggests marital discord.

A qualified clinical psychologist conducted all intervention sessions. The CBT+BMT arm had the following interventions. Cognitive behavioural therapy (Individual therapy for patients) included psychoeducation, relaxation therapy, activity scheduling, social skills training, systematic desensitization, exposure techniques, distraction techniques, behavioural experiments, and downward arrow technique (verbal challenge of dysfunctional assumptions). Individual therapy was provided over 12 to 15 sessions with each session of the duration 40 to 45 minutes. Participants were provided a CBT workbook and taught to complete a thought record worksheet that was reviewed with the clinical psychologist during the weekly meetings. Behavioural marital therapy (Couple intervention) included supportive psychotherapy techniques; empathizing, reassurance, prestige suggestion and environmental modification and working with specific identified problems such as communication patterns, problem solving, sexual dysfunctioning, and reducing conflict by trouble shooting. Couple interventions were provided over 4 to 10 sessions with each session of the duration one hour. The interventions in the CBT+BMT arm were provided over a 2.5 month period. The standard of care or the control arm received psychoeducation provided over one session and continued on maintenance pharmacotherapy as advised by the treating psychiatrist.The tools (quality of life and marital quality) were re-administered to participants and spouses in both groups at a follow up visit three and half months after baseline assessment (one month after completion of intervention in the CBT +BMT group).

Chi-square test, student’s t-test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to compare between group differences in socio-demographic medical variables, and baseline WHO-QOL and marital adjustment. The paired student’s t-test was used to compare the mean scores of the WHO QOL and marital adjustment scores pre and post intervention within groups and between groups. The potential association between years of marriage and duration of illness and QOL and marital quality and between QOL and marital quality was explored using ANOVA. The between groups effects of the intervention were analysed using effect sizes(Cohen’s d). An effect size of 0.2 represents a small effect, 0.5 a moderate effect, and 0.8 a large effect [8]. An effect size > 0.2 is considered as a benchmark for clinically meaningful effects [9] and may warrant a change in clinical practice.

Results

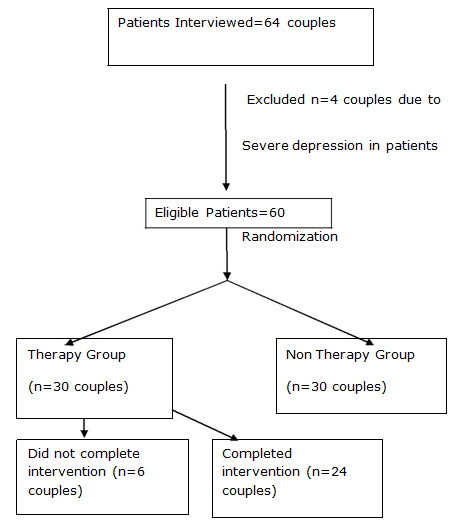

Recruitment for the study took place from April 2005 to May 2008. [Table/Fig-1] shows the flow of participants through the study. A total of 54 couples completed the study- 24 in the CBT + BMT group and 30 in the standard of care or control group. Participants age ranged from 25 to 55 years and 34 (62.96%) of participants were females. The majority of participants in the study were diagnosed, based on the ICD-10 criteria, with obsessive compulsive disorders (n=27, 50.00%) and phobic disorders (n=16, 29.63%) including eight participants with agoraphobia, seven participants with social phobia and one participant with a specific phobia. An additional seven participants (12.96%) had panic disorders and four participants (7.41%) had generalized anxiety disorder. The success of the randomisation procedure was assessed using chi-square tests, student’s t-test and ANOVA. We did not find any significant between group differences on any of the socio-demographic variables (age, sex, education, occupation, years of marriage, type of family and family income), diagnosis, age at onset of illness, or duration of illness (all p-values >0.10). Additionally, the groups did not differ in the baseline WHOQOL scores of participants, baseline WHOQOL scores of spouses of participants, baseline marital adjustment scores of participants and baseline marital adjustment scores of spouses of participants (all p-values > 0.10). [Table/Fig-2] presents the baseline WHOQOL scores and baseline marital adjustment scores of participants and spouses of participants in the study. Four of the 30 participants in the therapy group dropped out because they were unable to return as per the requirements of the intervention protocol (two after the first individual session, and one each after the third session and fourth session respectively), and two participants in the therapy group dropped out because the spouses could not come for intervention. There was no statistically significant difference between the 24 participants in the therapy group that remained in the study and the six participants of the same group that dropped out from the study. The six participants that dropped out from the study were not considered for further analysis.

Flow Chart of Patient enrolment

Baseline WHOQOL and Marital adjustments scores of participants and spouses in the study

| Item | CBT+BMT Participant (mean score ±SD) | Standard of care group participant (mean score ±SD) | CBT+BMT group spouse (mean score ±SD)) | Standard of care group spouse (mean score ±SD) |

|---|

| WHOQOL Domains |

| Physical | 56.66± 12.75 | 54.63 ± 25.67 | 70.00± 21.81 | 71.77 ± 16.66 |

| Psychological | 45.79± 16.44 | 53.83 ± 22.36 | 65.17± 20.30 | 59.83 ± 18.50 |

| Social | 52.75± 25.28 | 51.57 ± 21.58 | 64.37± 15.59 | 66.9 ± 18.89 |

| Environmental | 70.35± 4.59 | 63.80 ± 16.22 | 70.38± 4.59 | 63.80 ± 16.22 |

| Marital Adjustment | 94.17± 11.58 | 88.40 ± 27.52 | 97.12± 20.29 | 92.17 ± 22.55 |

Post intervention, the WHOQOL scores of participants in the CBT + BMT group was significantly better than scores of participants in the standard of care group for two domains- psychological domain and social domain but did not differ significantly between groups for the physical or environmental domain [Table/Fig-3]. Post intervention, participants in the CBT+BMT group showed significantly better WHOQOL scores in the psychological (paired t-test, t=-5.25, df=46, p=<0.001) and social domains (paired t-test, t=-2.08, df=46, p=0.04).

WHO quality of life at final assessment of participants

| Domain | CBT+ BMT* group Mean ± SD | Standard of Care group Mean ± SD | f-value (ANOVA) | Degrees of Freedom | p-value |

|---|

| Physical | 58.25± 11.92 | 56.63 ± 25.67 | 0.08 | 53 | 0.77 |

| Psychological | 69.00± 14.08 | 52.83 ± 22.36 | 7.98 | 53 | 0.006* |

| Social | 65.75± 17.28 | 51.57 ± 21.58 | 4.54 | 53 | 0.02* |

| Environmental | 70.35± 4.59 | 63.80 ± 16.22 | 3.69 | 53 | 0.06 |

| * Cognitive Behavior therapy + Behavior Marital Therapy |

Post intervention, the WHOQOL scores of spouses of participants in the CBT + BMT group was significantly better than scores of spouses of participants in the standard of care group for two domains- psychological and environmental domains but did not differ significantly between groups for the physical or social domain [Table/Fig-4].

WHO quality of life at final assessment of spouses of participants

| Domain | CBT+BMT* group Mean ± SD | Standard of Care group Mean ± SD | f-value (ANOVA) | Degrees of Freedom | p-value |

|---|

| Physical | 70.00± 17.50 | 70.77 ± 16.67 | 0.03 | 53 | 0.87 |

| Psychological | 72.58± 15.27 | 57.83 ± 18.50 | 9.86 | 53 | 0.003* |

| Social | 71.25± 13.33 | 65.90 ± 18.90 | 1.37 | 53 | 0.25 |

| Environmental | 74.83± 6.95 | 61.80 ± 16.22 | 13.47 | 53 | 0.0006* |

| * Cognitive Behavior therapy + Behavior Marital Therapy |

Post intervention, the overall marital adjustment scores of participants in the CBT + BMT group was significantly better than scores of participants in the standard of care group and specifically for the following domains- understanding, despair, discontent, self-disclosure and role functioning [Table/Fig-5]. Post intervention, participants in the CBT+BMT group showed significantly better overall marital adjustment scores (paired t-test, t=5.65, df=46, p=<0.001) while participants in the standard of care group did not show any significant difference in the marital adjustment scores (paired t-test, t=0.00, df=58, p=1.00).

Marital adjustment score at final assessment of participants

| Domain | CT+ BMT group* Mean ± SD | Standard of Care group Mean ± SD | F Value (ANOVA) | Degrees of Freedom | p-Value |

|---|

| Understanding | 9.12 ± 2.57 | 12.80 ± 5.45 | 9.22 | 53 | 0.004* |

| Rejection | 18.71 ± 4.18 | 20.56 ± 7.87 | 1.09 | 53 | 0.30 |

| Satisfaction | 5.75 ± 2.72 | 6.20 ± 3.61 | 0.30 | 53 | 0.59 |

| Affection | 8.25 ± 1.54 | 9.60 ± 5.40 | 1.40 | 53 | 0.24 |

| Despair | 3.67 ± 0.82 | 4.83 ± 1.71 | 9.48 | 53 | 0.003* |

| Decision making | 8.21 ± 2.46 | 9.10 ± 4.72 | 0.70 | 53 | 0.41 |

| Discontent | 3.79 ± 1.58 | 5.30 ± 1.84 | 10.09 | 53 | 0.002* |

| Dissolution potential | 1.5 ± 0.83 | 1.30 ± 0.84 | 0.76 | 53 | 0.38 |

| Dominance | 4.91 ± 1.38 | 4.13 ± 2.24 | 2.25 | 53 | 0.14 |

| Self disclosure | 4.37 ± 1.31 | 6.40 ± 1.79 | 21.40 | 53 | <0.001* |

| Trust | 1.21 ± 0.41 | 1.17 ± 0.46 | 0.12 | 53 | 0.73 |

| Role functioning | 4.83 ± 1.16 | 7.00 ± 2.58 | 14.44 | 53 | 0.0004* |

| TOTAL | 74.33 ± 12.72 | 88.40 ± 27.52 | 5.34 | 53 | 0.02* |

* Cognitive Behavior therapy + Behavior Marital Therapy

Post intervention, the overall marital adjustment scores of spouses of participants in the CBT + BMT group was significantly better than scores of spouses of participants in the standard of care group and specifically for the following domains- understanding, rejection, affection, decision making, discontent, self-disclosure and role functioning [Table/Fig-6]. Post intervention, spouses of participants in the CBT+BMT group showed significantly better overall marital adjustment scores (paired t-test, t=5.01, df=46, p=<0.001) while spouses of participants in the standard of care group did not show any significant difference in the marital adjustment scores (paired t-test, t=-0.76, df=58, p=0.45).

Marital adjustment score at final assessment of spouses of all participants

| Domain | CBT+BMT* group Mean ± SD | Standard of Care group Mean ± SD | F Value (ANOVA) | Degrees of Freedom | p-Value |

|---|

| Understanding | 8.91 ± 1.63 | 13.03 ± 4.87 | 15.69 | 53 | 0.0002* |

| Rejection | 17.54 ± 3.07 | 23.10 ± 5.44 | 19.86 | 53 | <0.001* |

| Satisfaction | 7.08 ± 1.69 | 6.70 ± 3.80 | 0.21 | 53 | 0.65 |

| Affection | 9.08 ± 1.86 | 11.47 ± 4.41 | 6.10 | 53 | 0.02* |

| Despair | 3.62 ± 1.05 | 3.97 ± 1.50 | 0.89 | 53 | 0.35 |

| Decision making | 8.21 ± 2.00 | 10.5 ± 4.65 | 5.06 | 53 | 0.03* |

| Discontent | 3.00 ± 1.32 | 5.43 ± 1.98 | 26.77 | 53 | <0.001* |

| Dissolution potential | 1.25 ± 0.85 | 1.20 ± 0.55 | 0.07 | 53 | 0.79 |

| Dominance | 4.37 ± 1.41 | 4.63 ± 2.01 | 0.28 | 53 | 0.60 |

| Self disclosure | 4.46 ± 1.28 | 6.43 ± 2.50 | 12.33 | 53 | <0.001* |

| Trust | 1.17 ± 0.38 | 1.57 ± 0.97 | 3.61 | 53 | 0.06 |

| Role functioning | 5.71 ± 1.37 | 9.13 ± 3.31 | 22.57 | 53 | <0.001* |

| TOTAL | 74.42 ± 9.04 | 97.16 ± 22.55 | 21.57 | 53 | <0.001 |

* Cognitive Behavior therapy + Behavior Marital Therapy

Clinically meaningful effect sizes for the CBT+ BMT intervention were evident for the marital adjustment scores among participants and their spouses, and for the psychological, social and environmental domains of the WHOQOL [Table/Fig-7].

Effect sizes for the interventions

| Outcome measure | Effect size (Cohen’s d) | 95% Confidence intervals |

|---|

| Marital adjustment-patients | 0.63 | 0.07, 1.17 |

| Marital adjustment-spouses | 1.29 | 0.69, 1.86 |

| Patients-WHO QOL |

| Physical | 0.11 | 0.04, 0.25 |

| Psychological | 0.84 | 0.27, 1.39 |

| Social | 0.72 | 0.15, 1.26 |

| Environmental | 0.52 | 0.02, 1.56 |

| Spouses-WHO QOL |

| Physical | 0.05 | 0.001, 0.40 |

| Psychological | 0.86 | 0.29, 1.41 |

| Social | 0.32 | 0.22, 0.86 |

| Environmental | 1.01 | 0.42, 1.56 |

Discussion

The CBT and BMT group had significant improvements in quality of life and marital adjustment compared to the standard of care group. Effect sizes showed clinically meaningful and statistically significant effect sizes among participants and spouses in the CBT +BMT group for marital adjustment and for all WHOQOL domains except the physical domain.

The present study is consistent with previous literature that has demonstrated a significant benefit in quality of life with CBT [10–15] and with prior literature on the benefits of BMT [16–22]. The effects of combining CBT and BMT in the management of anxiety disorders is a value addition to the literature especially from India. Cognitive behaviour therapy helps individuals with anxiety disorders gain a different perspective of their problems leading to a change in their thought processes and teaches individuals to identify and dispute irrational beliefs replacing them with more positive, rational alternatives. Relief from the effects of anxiety symptoms might have helped patients relate better with their spouses. In this study,we found that CBT+BMT significantly improved the psychological and social domain quality of life as well as marital adjustment supporting the premise that CBT+BMT can help individual gain better control over their behaviour.

Involving the spouse in the therapy provides the spouse a better understanding of the problems faced by the person with anxiety disorder, the proposed management strategy and the expected improvement with a realistic expectation from the management process. All these factors could have contributed to improved quality of life in spouses of patients in the therapy group that itself may contribute to reduced anxiety in participants through better marital adjustment.In this study, we found that the spouse showed significant improvement in the psychological and environmental domains of the quality of life as well as overall marital adjustment post intervention. Behavioural marital therapy for the couple with marital discord simultaneous to CBT for the individual with anxiety disorder helped to improve the marital adjustment and relieve stress or anxiety related to marital adjustment. An improved understanding of the thought process of the person with anxiety disorder may help the spouse adjust better as well as become a trusted co-therapist.

There are several limitations to the study. Although we could establish a beneficial effect for CBT+BMT in persons with anxiety disorders and marital discord, we could not attribute a proportionate improvement between CBT and BMT. A trial that compares CBT+BMT to CBT alone will provide more evidence in this regard. The relatively short duration of follow up is another limitation with longer follow useful to determine long term benefits of CBT+ BMT.The smaller size of the subgroups may also be considered as a limitation although the overall sample size was adequate to detect statistically significant differences.

To conclude, the present study supports the use of CBT and BMT for persons with anxiety disorders and marital discord and involvement of the spouse in the therapy. Assessing the marital adjustment for persons with anxiety disorders and their spouses at baseline will be a useful addition to therapy.

* Cognitive Behavior therapy + Behavior Marital Therapy

* Cognitive Behavior therapy + Behavior Marital Therapy