Osteochondromas are commonly encountered benign tumours and they are characterized by cartilage capped bony growths that project from the surface of the affected bone. Osteochondromas tend to grow eccentrically rather than centrifugally. We are reporting a case of an 18-year-old male, who had presentation of a large, hard, irregular swelling over anterolateral aspect of his right leg. There was no neurovascular deficit in the extremity. Computed tomography showed that the origin of the tumour was probably proximal fibula. En-block excision of mass was done. A histopathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of a benign osteochondroma. Patient had uneventful recovery without any evidence of recurrence.

Case Report

An 18-year-old male presented with pain and swelling over anterolateral aspect of right proximal leg. Initially, it was small in size and painless, which later progressed over a period of three years, became painful and grew to the present size. Pain was dull aching in nature, which was aggravated on movement and relieved on rest. There was no history of trauma or fever. On clinical examination, a large swelling was seen over rt. proximal leg, on anterolateral aspect, of size which was approximately 10 x 10 x 8 cm. Swelling gradually increased from approximately 3 x 4 cm, when it was first noticed three years ago, to the present size. The swelling was irregular, hard, non-tender and fixed to bone. The movement in the knee joint was not restricted; also, there was no neurovascular deficit in the extremity.

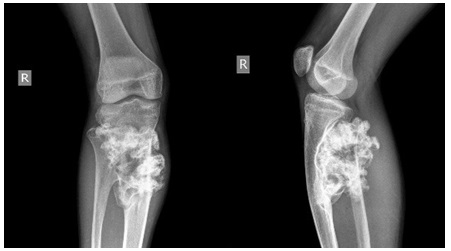

Plain radiographs (AP and lateral view) of leg with knee were taken, which revealed a large cauliflower like growth arising from proximal fibula, along with scalloping of tibia [Table/Fig-1].

Plain radiograph AP and Lateral view of leg with knee showing large cauliflower like growth arising from proximal fibula along with scalloping of tibia

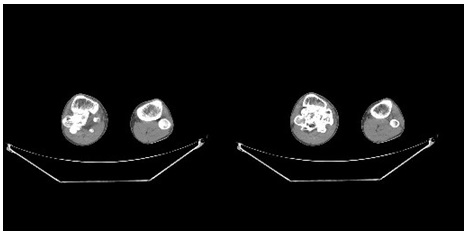

Computed tomography of right leg revealed a large growth arising from proximal fibula, with involvement of proximal tibia [Table/Fig-2]. Other laboratory investigations were normal.

Computed tomography of right Leg showing large growth arising from proximal fibula along with involvement of proximal tibia

After doing a complete evaluation under combined spinal epidural anaesthesia, en-block excision of tumour was performed and a small portion of head of fibula was left, where fibular collateral ligament was attached [Table/Fig-3] Patient. was placed in supine position, with a sandbag placed underneath the affected buttock. A tourniquet was applied after exsanguination which was achieved by limb elevation for 3-5 minutes. A linear incision was taken just posterior to fibula, along the line of biceps femoris tendon and after a superficial surgical dissection, common peroneal nerve was isolated. The nerve was mobilized and it was retracted anteriorly by using a strip of corrugated rubber drain. Muscles were stripped and fibula was exposed. En-block excision of tumour was performed. A single dose of intravenous antibiotics was given pre-operatively and this was continued for five days, along with analgesics and antiinflammatory drugs after surgery. A long leg slab was applied, with the ankle in neutral position, to prevent early muscle contracture and to help in pain management.

Post-operative radiograph after En-block excision of tumour, small portion of head of fibula was left where fibular collateral ligament was attached

Histopathological examination of excised tumour confirmed the benign nature of osteochondroma, without any evidence of a malignant transformation. The patient’s recovery was uneventful, with full neurological functions. He was subsequently followed up and showed no evidence of recurrence after 1 year of surgery.

Discussion

An osteochondroma was first described by Sir Astley Cooper, in 1818. It is the most common benign developmental tumour of the appendicular skeleton, which is characterized by an abnormal, ectopic, endochondral ossification around the physis. Osteochondromas account for 34% of the benign cartilage tumours and 8% of all bone tumours. These growths are comprised of bone which is surrounded by a cap of cartilage. Although this disease can occur spontaneously, it has been estimated that whatever the aetiology [neoplastic or traumatic], patients with solitary osteochondromas typically present with non-tender, slow-growing masses. Occasionally, fractures of the pedunculated osteochondromas can occur. Mass effect seen on adjacent structures such as bone [especially, when they occur in the forearm and leg], nerves, vessels, muscles, or even in the spinal cord, can also be symptomatic.

The incidence of primary bone tumours in the fibula is 2.5% [1].The most common tumours found in the proximal fibula are osteochondromas, giant cell tumours, osteosarcomas, and Ewing’s tumours. Osteosarcomas and Ewing’s tumours tend to grow in a centrifugal fashion, while osteochondromas grow eccentrically. Although they are most commonly located at the peripheries of the most rapidly growing ends of long bones, the lesions are also frequently found in the vertebral borders of the scapulae, ribs, and iliac crests. Osteochondromas may occur in the tarsal and carpal bones; however, they are often less apparent. Exostoses are initially recognized and diagnosed in the first decade of life, in over 80% of individuals with Hereditary multiple exostoses (HME) and are most commonly first discovered on the tibia or scapula, as these are often the most conspicuous locations [2,3]. Patients with exostosis tend to enlarge in size, while the physes is openly proportionate to the overall growth of the patient. The growth of the osteochondroma usually ceases at skeletal maturity. Lesions have been infrequently reported to spontaneously regress during the course of childhood and puberty.

There have been many theories that have proposed to explain the aetiology of osteochondromas; Virchow’s physeal theory, where portion of plate separates and rotates 90 degrees, Keith’s Plate defect theory which was proposed in 1920 and supported by studies done by D’Ambrosia and Ferguson in 1968. They produced exostoses by physeal cartilage transplantation, which demonstrated and supported the concept that exostoses were developmental physeal growth defects [4]. Muller’s theory of presence of small nests of cartilage are a few to mention. Present thought regarding aetiology of osteochondroma is a misdirected growth of a portion of the physeal plate.

Osteochondromas may be sessile or pedunculated and in 90% of the cases, they are solitary. Tumour is usually covered by a 1-3 mm cartilaginous cap, which is composed of hyaline cartilage, without cellular atypia. Osteochondromas commonly present as masses or bony lumps; however, progressive enlargement of a osteochondroma may cause tendon, vessel and nerve compressions or a skeletal deformity. As was reported by Shapiro et al., it may be associated with ulnar deformation, radial head dislocation, and rotation limitations in the upper extremity; coxa valga, genu valgum, genu recurvatum, obliquity of distal tibial physis and LLD in the lower extremities. A fracture which occurs through the stalk, a pseudoaneurysm formation, infection, ischaemic necrosis, and a malignant transformation may result in appearance of symptoms in adults [2,5–8]. A malignant transformation to a chondrosarcoma [approximately 1% for solitary and 20% for patients with multiple lesions] is rare and it should be suspected if tumour is suddenly increasing in size and if there is increase in pain and other symptoms. The diagnoses of osteochondromas are always made by doing radiographical studies of the affected areas. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance are useful for concomitantly demonstrating bony, vascular and soft tissue lesions. Vascular lesions can be diagnosed by angiography or colour–flow Doppler ultrasonography [9]. Bone scans are also helpful for making a diagnosis, but they cannot differentiate between benign active exostoses and chondrosarcomas. Lange et al., correlated the X-ray, bone scan and histologic findings in 24 patients with solitary or multiple exostoses and found malignant degenerations in 2 of 25 exostoses. Both exostoses were found to be in an “active” pattern by bone scan. The bone scan could not however, differentiate benign active exostoses and chondrosarcomas.

A proximal fibular osteochondroma may distort the normal anatomical course of nerves and vessels and it may lead to vascular compression syndromes and a pseudoaneurysm or peroneal nerve paralysis [10–13]. In our case, the main concern was size of the swelling, its abnormal location and involvement of neurovascular bundle posterior to the knee, but both dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial artery were easily palpable and also, neurological examination was normal. Another concern was the suspicion of a malignant transformation, but histopathological examination of resected specimen confirmed its benign nature, without evidence of any malignant transformation. Aggressive excisions of these proximal tumours may lead to destabilization of the proximal tibiofibular joint. Careful staging and planning of the surgical approach and procedure, is therefore of utmost importance, while proximal fibular tumours are being dealt with.

In most cases of solitary osteochondromas, treatment consists of a careful observation over time [2,3]. If there is vascular involvement, treatment of bone and vascular lesions is performed simultaneously. After osteochondroma resection, repair of the vascular lesion is performed according to lesion size and type. The surgical treatment of vascular complications of osteochondromas is recommended as an emergency procedure, to avoid irreversible lesions such as occlusions of distal vessels or venous thrombosis, with risk of a pulmonary embolism. Opinions about the need of prophylactic resections for all osteochondromas, in case of multiple hereditary osteochondromas, are controversial.

Recurrence of an exostosis after its surgical excision, although it is rare, has been observed and it may be attributed to incomplete removal of lesions which are contiguous with the physis in growing children or incomplete removal of the cartilaginous cap. Mirra reiterated the importance of complete resection of the cartilaginous cap, to prevent recurrence. Prognosis after excision is excellent.

Conclusion

Although most of the osteochondromas in children should be treated conservatively until skeletal maturity, those affecting the proximal tibia or fibula should be treated with surgical excisions, in order to prevent knee deformities, vascular compression syndromes pseudoaneurysms or peroneal nerve paralysis or even fractures caused by the expanding nature of the benign tumour. The giant osteochondroma seen in our patient did not show any malignant change and thus, this refutes the common notion regarding the sarcomatous change in a late growing osteochondroma.

[1]. Unni K, Dahlin’s Bone Tumors: General Aspects and Data on 11,087 Cases 1996 PhiladelphiaLippincot-Raven Publishers [Google Scholar]

[2]. Ryckx A, Somers Jan FA, Allaert L, Hereditary Multiple ExostosisActa Orthopaedica Belgica 2013 79:597-607. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Saglik Y, Altay M, Unal VS, Basarir K, Yildiz Y, Manifestations and management of osteochondromas: a retrospective analysis of 382 patientsActa Orthopaedica Belgica 2006 72:748-55. [Google Scholar]

[4]. D’Ambrosia R, Ferguson AB, Jr, The formation of osteochondroma by epiphyseal cartilage transplantationClinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 1968 61:103-15. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Anderson RL, Jr, Popowitz L, Li JK, An unusual sarcoma arising in a solitary osteochondromaThe Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American volume 1969 51:1199-204. [Google Scholar]

[6]. El-Khoury GY, Bassett GS, Symptomatic bursa formation with osteochondromasAJR American Journal of Roentgenology 1979 133:895-8. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Ferriter P, Hirschy J, Kesseler H, Scott WN, Popliteal pseudoaneurysm. A case reportThe Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American volume 1983 65:695-7. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Unger EC, Gilula LA, Kyriakos M, Case report 430: Ischemic necrosis of osteochondroma of tibiaSkeletal Radiology 1987 16:416-21. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Douis H, Saifuddin A, The imaging of cartilaginous bone tumours. I. Benign lesionsSkeletal Radiology 2012 41:1195-212. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Mnif H, Koubaa M, Zrig M, Zammel N, Abid A, Peroneal nerve palsy resulting from fibular head osteochondromaOrthopedics 2009 32:528 [Google Scholar]

[11]. Cardelia JM, Dormans JP, Drummond DS, Davidson RS, Duhaime C, Sutton L, Proximal fibular osteochondroma with associated peroneal nerve palsy: a review of six casesJournal of Pediatric Orthopedics 1995 15:574-7. [Google Scholar]

[12]. Vassilios Andrikopoulos GS, Gerasimos Papacharalambous, Ioannis Antoniou, Konstantinos Tsolias, Panagiotis Panoussis, Arterial Compromise Caused by Lower Limb OsteochondromaEndovascular Surg 2003 37:185-90. [Google Scholar]

[13]. Boris M, Holzapfel GS, Richard Wagner, Werner Kenn, Rainer Meffert, Popliteal Entrapment Syndrome Caused by Fibular OsteochondromaAnnals of Vascular Surgery 2011 25:982.e5-e10. [Google Scholar]