Introduction

Private health sector is the dominant health care sector in India and it employs approximately 80% of the registered health care providers. Not surprising that this sector manages the two most common preventable causes of death in children, by distributing two-thirds of the Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS) for diarrhoea and managing more than a quarter of Acute Respiratory Infections (ARIs) [1]. However, challenges of regulation, quality, accountability and collaboration with other sectors hinders its potential to deliver public health goals, such as the reduction of under five mortalities [2]. Also, the privatization of health services poses unique ethical dilemmas and challenges for developing countries [3,4]. We, thus set out to review the evidence base regarding health care systems in India, regulation of private hospitals, financial models of health delivery, applicability of private-public mix, state of health insurance and policy issues, to understand and conceptualize the complex web of equity, ethics and management for health care. We then provide a model for the ethical delivery of services by taking a potential example of services undertaken for sick newborns and infants by private hospitals in India.

Search Strategy

A systematic search strategy was developed, to understand the broad issues of ethics, management and equitable delivery of health services within the health systems in India. A search of PUBMED, CINAHL, EMBASE and GOOGLE SCHOLAR was conducted by using the following search terms, “health systems” AND “India”, “health policy” AND “India”, “health insurance” AND India, “health economics” AND “India”, “private health sector” AND “India”, “Ethics” AND “health” AND “India”, “Health equity” OR “health equality” AND “India”. Abstracts were read for more than 500 articles and important publications were collected in full text. An initial search was conducted between April and May 2008 and broad themes were identified by using the approach of a thematic synthesis of qualitative data for systematic reviews [5,6]. The same search strategy was used for relevant policy issues of South Africa and Australia. A search for progress and newer developments in the areas of health systems, ethics, polices in India was conducted again in November 2013. No new themes emerged in the literature during the second review process, though the number of articles on health system issues, which emerged from India increased substantially.

Health Care Infrastructure in India

Public Health Care

India has a three-tier apex public health system. At the base, there is a vast network of 22,370 Primary Health Centers (PHC) which coordinate six sub-centrer and serve a population of about 30,000 people. In the middle, there is a community health centre which serves about 100,000 people, followed by district level hospitals [7, 8]. At the apex, are the tertiary level centrer which are generally in the form of medical schools. There are over 200 medical schools in major cities, with an increasing participation of private health sector [9]. The Government of India has further invested heavily for strengthening the rural health infrastructure, under the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) [10]. However, acute shortages of rural health care providers and teachers in medical schools and sub-optimal performance indicators of employed staff due to job satisfaction issues, raises questions on quality of service delivery within public health sector [11–15].

Private Health Care

The private health care sector is markedly heterogeneous, both in terms of regional heterogeneity (inter and intra-state, rural-urban and intra-urban differences) as well as provider heterogeneity (formally qualified providers with multiple health systems Allopathy, Ayurveda, Homeopathy, Naturopathy and Unani medicine and unqualified providers such as drug peddlers and quacks) [16]. To complicate matters further, there is substantial uncertainty on the number of health professionals, especially in the private health sector in India. A 1991 census estimated that there were about 300,000- 390,000 qualified allopathic doctors, about one million Rural Private Practitioners, and over 650,000 providers of other systems of medicine [17]. These are most likely gross underestimations and innovative approaches such as map- based health management information systems are being utilized to ascertain this robustly [18, 19]. Most of the qualified practitioners practise individually in out-patient settings or in their self-owned nursing homes. These nursing homes are usually five to thirty bed health facilities with inpatient and outpatient services, with co-location of pathology and other auxiliary services, depending on available resources. A large number of corporate hospitals (often more than 100 bed facilities) have been established with investments made by industry, pharmaceutical companies and foreign investments. Medical tourism undertaken by many of these hospitals is being actively promoted by the government of India, seeking to generate foreign exchange, which leads to social and ethical issues [20].

Utilization of Health Services

In the private and public health sectors of India, the splits for utilization of health services between primary, secondary and tertiary care sectors have been reported to be 48.1%, 24.1%, 15.1% and 60%, 21% and 19% respectively [21]. The utilization of private and public health services across the lower quintiles remains at 30-45%, but it rises in favour of private sector utilization to almost 70% among higher income quintiles [22]. Private corporate hospitals, though they utilize major investments, provide coverage to a very small proportion of population. A total of 77.4% of health expenditures in India is private, while only 20.3% is public. Non-governmental organizations and other supports contribute to 2.3% of expenditures. Public expenditures in India are amongst the lowest in the region (logging behind those of Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka). On the other hand, 98.4% of the private health expenditure is from households, in the form of out-of-pocket payments. A very small proportion comes from health premiums which are paid by employees and group insurance schemes.

Another important aspect of this sector are private pharmacies and prescription drugs are easily available due to little control of the authorities over the sale and licensing of drugs [23].

Regulation of Private Health Sector

The expansion of the private sector in India has forced a number of regulations, to promote quality of care and to protect consumers. The following three particular acts, the Consumer Protection Act, Medical Councils Act, and the Nursing Home Act, have provided basic guidelines for regulation of certain aspects of the health sector [24, 25]. However, effective implementation of these laws has remained a farce. The focus of the government, driven by political compulsions and paucity of resources, has been to ensure availability of basic services for a large section of the rural poor population and enforcement of regulations for sections which pay for their own care has been largely neglected. This may be contributing to increased violence against doctors in India [26].

In only few states where such legislations exist, the Nursing Home Act permits registered medical practitioners to provide services to patients who have any sickness and it categorizes basic minimum requirements in terms of infrastructure, manpower, paramedical staff and waste disposal. However, there are no provisions on the type of services that these hospitals can deliver, payment mechanisms for doctors, fees that these hospitals can charge for services, competitive practices which should be followed and the number of hospitals which can be allowed market entry. This goes against the fundamental definition of the areas of regulation made by Moran and Wood [27]. As a result, specialty services like cardiac surgery, neurosurgery and, intensive care are delivered by smaller hospitals. There is, thus, a vast possibility of exploitation of users, especially in developing countries, where poor awareness and knowledge among people make them highly vulnerable to receive sub-optimal quality care at exorbitant prices [28,29]. On the other hand, large private corporate hospitals, even with the necessary infrastructure, do not deliver these services to the poor against their contract with the government in the absence of enforcement, (a reciprocal arrangement for subsidized land and tax incentives) [30].

The second important regulatory act is the Consumer Protection Act which was enacted in 1986. This act broadly failed in achieving its objectives, as it did only little to curb medical negligence and malpractices and is often counter-productive, promoting unethical practices of over-investigations and unnecessary subspecialty referrals [31]. Medical Councils in India have failed to achieve any success in regulating the large numbers of individual practitioners, as they are under-resourced and lack necessary mechanisms for regulation.

How Can We Improve the Private Health Sector in India?

Improving the private health sector is a worthy goal, as it is a popular resource which is used by all social classes. It is unlikely that a “one size fit all” will work, as there many situational, structural, cultural and exogenous factors which influence policy implementation [2].

Some strategies highlighted by Mills et al., [32] have been used in India, while the potentials of others need to be explored. These include influencing consumers and promoting consumer protection by using Information, Education and Communication (IEC) activities, targeted use and distribution of vouchers that are exchanged for services from a private provider (feasible in India as a mechanism for identifying the disadvantaged groups through a system of ration cards, Below Poverty Line (BPL) cards exists), influencing private providers through training, regulatory, participatory and comprehensive approaches (such as professional organizations building on non-financial incentives of social recognition for providers), restructuring and regulating the market and role of government (the need for this has been highlighted in a study done in Madhya Pradesh [33], Contracting services [34] (some states have successfully initiated large scale contracts “Chiranjeevi Yojna”, “Janani Suraksha Yojna” to save lives of mothers and newborn [35,36], development of rural task force for villages by corporate hospitals [37], overcoming barriers such as inter-sectoral barriers of mistrust which hinder true dialogue due to social, moral and economic bases [38], expansion of telemedicine [39], discouraging practice of informal payments [40], and allowing listed companies to own hospitals, as the financial performances of hospitals run by listed companies are likely to be better [41].

We will now discuss some of the insights gained from the review of literature from South Africa and Australia.

Lessons from Regulation of Private Health Sector in South Africa

The key lessons learned from the government policies of South Africa for regulating health care in the private sector are [42,43]:

Restructuring of the public health system with decentralization of the services and use of a resource allocation formula, which is based on population weights, to distribute the national health budget between states on an equitable basis.

Changes in policy promoting self-regulation rather than direct state directed regulation, with an integrated regulatory mechanism.

‘State governments’ base evaluations of applications of private hospitals on location and capacity of existing private and public hospitals (“certificate of need process”) and they often involve a temporary moratorium on building of new hospitals.

Statutory prohibitions exist against doctors’ ownerships of shares in the hospital, control of emergency transport services and pharmacies and kickback arrangements of medical supplies.

Alternative reimbursement models have been developed, maximum prices have been set, processes of National Health Reference Price List (NHRPL) have been endorsed and strengthened to establish true costs and to ensure transparency in private hospital tariff. Payments for private medical schemes are reviewed on a timely basis, to prevent uncontrolled claims and to increase competitiveness.

Tax subsidies are encouraged for the training of health care workers in private sector.

Doctors in the private health sector have been mandated to prescribe drugs by using non-proprietary or generic drug names and pharmacists have been allowed to substitute a generic drug if a doctor prescribes a branded version.

Public-private interactions made for sharing resources creating greater access, efficiency and enhanced sharing of health information systems.

Insurance industry is community rated, which improves cross-subsidization of the ill and elderly within medical schemes, and limits the extent to which high-risk groups are excluded.

Lessons from Regulation of Private Health Sector in Australia

Australia’s health care system changed remarkably over the last two decades, as a result of change in policy, to encourage private health insurance and to relieve financial pressure on the public health care sector [44]. These policies included (a) Upto a 30% premium rebate for the public buying of private health insurance, (b) health insurers offering lifetime enrolment on existing terms and the future relaxation of premium regulation by permitting premiums to increase with age, and (c) a mandate for insurers, to offer complementary coverage for bridging the gap between actual hospital billings and benefits which were paid. This has made an impact by reducing number of individuals who used public hospital systems [45].

A word of caution also emerges from Australia, for a more equitable case-mix of utilization of services. The workload of private hospitals is characterized by a high proportion of surgical procedures in general services (48.1%), while intensive care and emergency services (75%) continue to be provided by the public system [46]. Further, a negative impact was noted on ‘maternity care’, in terms of higher birth interventions and operative birth rates in private hospitals in New South Wales (NSW) .

Strategies such as co-location of public and private hospitals, used for creating a new hybridized ‘health care’ space between two sector hospitals [47], benchmarks and performance of private hospitals, to help informed decision making by consumers [48] and cost restraints on pharmaceutical spending by regulating reimbursement based on drug safety, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, have made a positive impact [49]. Further, initiatives in the form of development and funding of geographically based divisions of general practice has provided an organization structure to individual practitioners, with links to the rest of health care structures.

Appraisal of Government Policies in India: Issue of Distributive Justice

The recent policy initiatives and experiences in the private health sector in India raise questions on distributive justice in India [30]. Confederation of Private Sector Initiatives in Health Care estimated a requirement of 60,000 super specialty beds every year, with the current status of only 3,000 beds per year being planned, creating a general impression that establishment of such facilities will solve the problems in health care and there by divert the attention of policy makers for further subsidies. In contrast, no pilot studies were conducted on the technical, operational and administrative feasibility of NRHM program before the initiation of this ambitious program, to strengthen rural health care infrastructure [14]. The Foreign Investment Promotion Board in India approved 100 million US$ of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) during the period from 1991 to 1997, with one-third in Delhi and the rest in major towns of India. No robust mechanisms exist for giving special tax incentives to corporate hospitals, to establish health facilities in rural areas of India. Few initiatives have been taken by the government, to increase the investments made by the private health sector in public primary health care centres. Some states have developed innovative non-tax financing by creation of autonomous hospital development committees (Kerala) or Medicare relief societies (Rajasthan).

The health insurance sector is limited to about 1.6 million people of upper middle social classes and the government has yet to effectively implement innovative schemes for the poor on a national scale.

An analysis done by Mahal [50] clearly showed that the aggregate of the public and private health sector spending in India (5.6% of GDP, mostly in the form of out-of-pocket expenses) was higher than China, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. It has also been estimated that Indians spent US$ 19.5 per capita on health and due to OOP expenditures, the poorest 20% lose more than two-thirds of their income and leave 25% of their ailments untreated. At a national level, richest 20% enjoy 31% subsidies (three times to the poorest 20% in India). These inequities are more in rural areas and they differ among states.

Private and State Health Insurance in India

Dror [51] highlighted seven characteristics of poor households which are useful for policy makers, for developing health insurance schemes.

Willing ness to pay 1% of their household income on health insurance.

The cost of drug consumptions is similar to cost of hospitalizations.

Insulation effect of larger households with fewer illness episodes and less risk to insurers.

Intra-house information, resource and asset sharing and demographic balancing lower the prevalence of illness.

Can participate actively in the health insurance package.

Poor communities differ from each other and thus, “one size fits all” insurance product is unsuited to poor.

Significant proportion of cost of insurance can be contributed by people.

Community Based Health Insurance Projects

Several Community Health Insurance (CHI) schemes have been initiated by non-governmental organizations (NGO) to target the poorest and vulnerable households [52,53]. Three commonly used models are: NGOs acting as both insurers and providers, NGOs acting as insurers and the services being purchased from private providers, NGOs acting only as a link between the insurers and private providers. However, these schemes have been showing provide only partial protection to the poor against catastrophic health expenditure [54].

The Government of India is promoting the private health insurance companies and it has passed an Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority Bill (IRDA). However, the likely adverse effects of private health insurance on increase in costs of care, suggest some sort of cross-subsidy from the rich to the poor, which may be the most desirable strategy [50].

Public-Private Initiatives in India

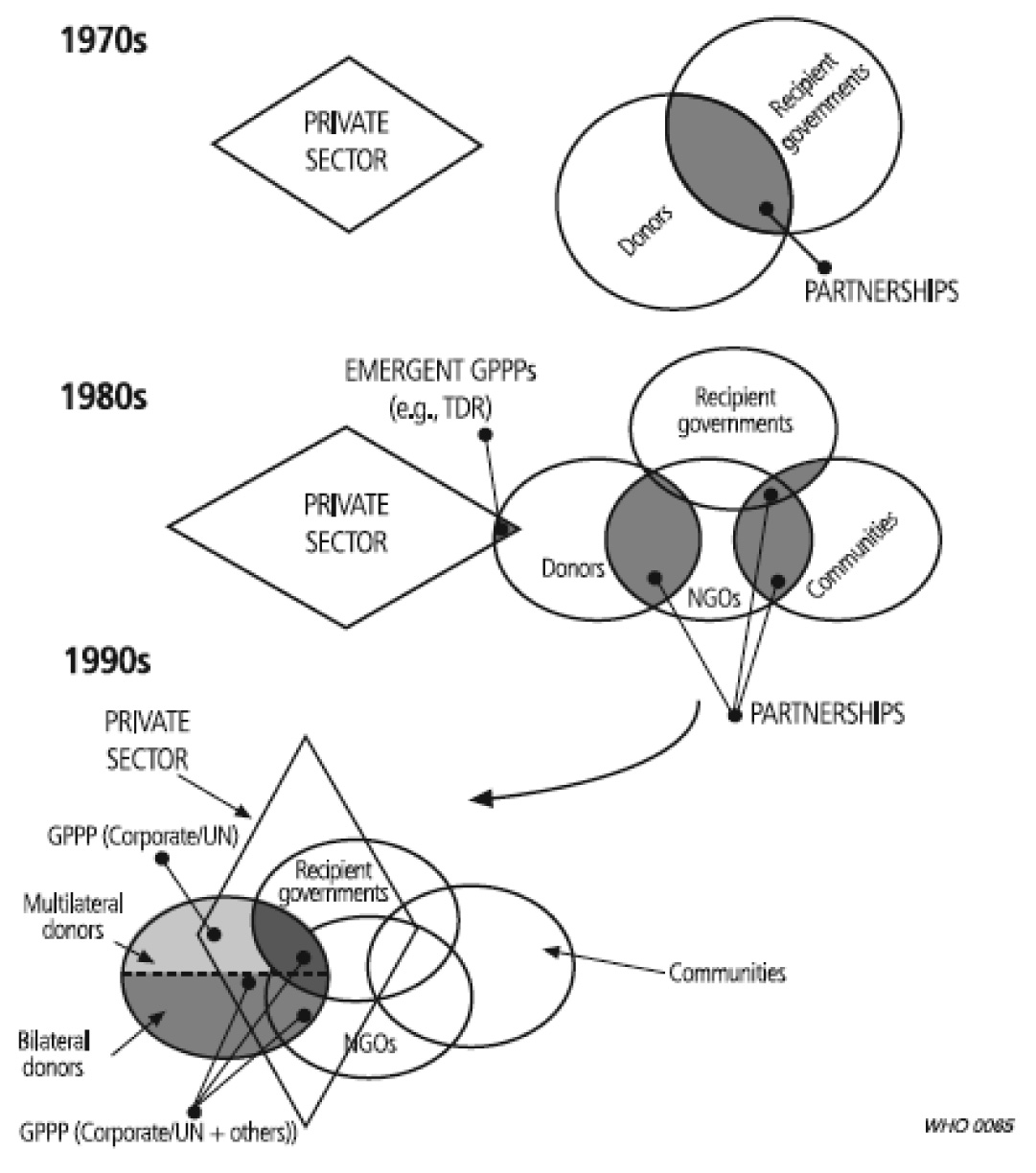

There is a shift in global public-private initiatives in recent decode [Table/Fig-1] [55]. Scaling up of facilities for the reduction of neonatal services at a district health system in south India has been shown by upgrading of the neonatal services at public district hospitals by private funds from NGOs [56]. The National Committee of Healthcare, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and Quality Council of India, has established National Accreditation standards for hospitals in India. The Government of the state of Maharashtra in western India has formulated transparent guidelines and regulations for private sector management of primary public health facilities. Contracting of services such as laundry, kitchen and cleanliness services by state governments of Rajasthan, Delhi, and Punjab, (India) to private players have given good results. The states of Himachal Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh and Karnataka, (India) have formed trusts with leading private institutions, to establish medical colleges and reputed private institutions have been given permissions to run nursing schools.

Shift in global private-public relationships There is a convergence of public and private-for-profit sectors after an initial period of minimal collaboration, to current full scale endorsement of open partnerships (55)

Ethical Issues and Model for Service Delivery With Private Health Sector

In developing countries, ethical questions which may arise for health providers, especially for evolving private hospitals are:

Different perspectives of health care providers and management may create conflicts for the type, quality and methods of service delivery. What to do from the health care provider’s perspective if management is not keen to upgrade services for specialties which are needed but are not financially luring options?

What are the patients’ rights in the setting of resource limited healthcare settings? Are they different in different contexts?

Inadequate staffing results in dilemmas on work-hours of the employees. Is it justified to accept mistakes and errors on the part of overworked employees?

Who is responsible for neonatal deaths in the absence of adequate referrals and transport services in public or private health systems?

Who is responsible if newborn babies come to private hospitals but cannot afford care and die or suffer non-recoverable damages during transport to other hospitals?

Can new private hospitals charge user fees which are similar to those which are charged by developed hospitals for the partially developed services?

Singh [57] has argued that: ‘In view of our economic restraints, we should follow the philosophy of utilitarian ethics, based on the concept of “value for money” and focus our resources and efforts for the care of salvageable babies. The specific ethical questions which can be asked during the care of sick newborns are (a) Should we be concerned with the “best interests” of the child alone or global interests of the community, society or state? (b) Should NICU facilities be denied if families cannot afford it? How far should the governments with limited resources support the salvage of one such baby when many others can be saved elsewhere at lesser expenses? (c) Should future fertility of the couple or the gender of the child affect ethical decisions? (d) The concepts of destiny, will of God, the doctor-knows-the-best attitude and illiteracy, often mitigate the concepts of parental autonomy and informed consents of parents! How valid is an ‘informed consent’ in such a situation? (e) When survival of a high-risk baby is associated with a neuromotor disability, it may be unbearable for the family due to lack of social support system and inadequate facilities for the care of children with severe neuromotor disabilities. The forced survival of such a baby (if the baby was born in a public sector hospital with all facilities) may be more devastating for the family than its demise. Should the parents be allowed to decide to not attempt salvage? (f) What should be done when the family cannot further afford the ongoing expenses for providing medical care to their critically sick baby in a private hospital and when there is no public sector hospital nearby? and (g) Is it ethically justifiable to provide hi-tech and extremely expensive intensive care to a tiny baby of illiterate and economically destitute parents who are in a most probable situation, who are unlikely to be able to provide necessary care to the baby after discharge from the hospital?

Intergrated Model for Service Delivery

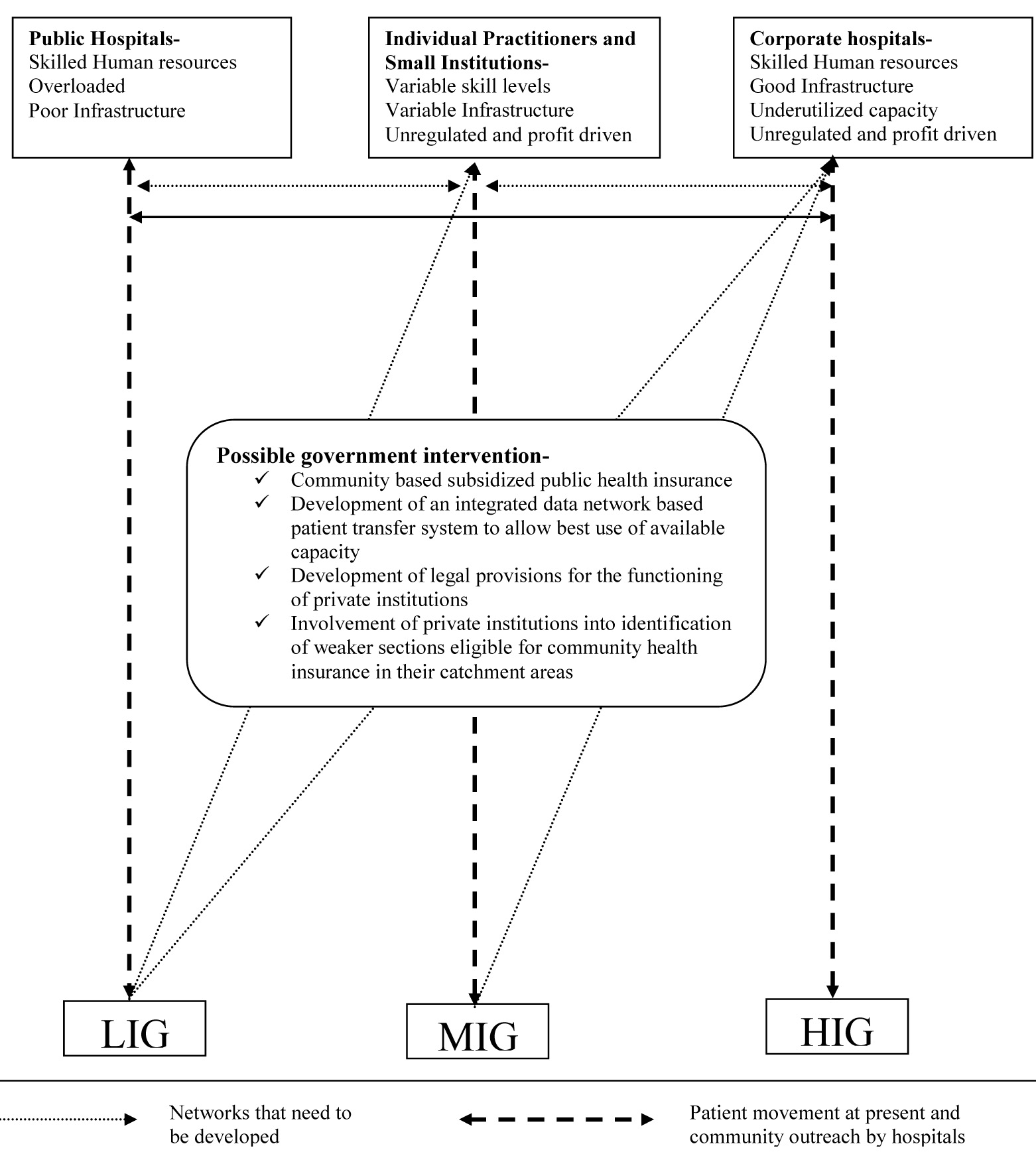

With this background literature review and personal experiences of authors in the public and private health sector of India, we suggest an integrated care model for ethical service delivery for sick children and newborns [Table/Fig-2]. This model incorporates both the supply and demand end stakeholders meeting their complex and varied needs [58]. As is evident at present, the patient flow among various social classes is highly demarcated, with public health facilities being utilized predominantly by the lower income quintiles [21]. Individual private health care providers are mostly excluded from the public health system and referral and transport systems are rudimentary [59,60]. This means that even if a sick child reaches the individual health care provider or a small community hospital, it may not be managed, referred and transported appropriately. If it reaches a public health facility, it is likely that infrastructure would be inadequate to provide appropriate care to it. This is why, an integrated system between the public and private hospitals has the greatest potential to make improvements in health services in India. Government can play a central role by coordinating, regulating and monitoring various stakeholders to maximize the utilization of resources. It can also chart guidelines for an increased participation and role of private hospitals to provide health care services to the poor through community based insurance schemes. A pilot project of prospective data collection and confirmatory factor analysis will lend further support to this model.

Collaborative model for providing ethical delivery of health services in India*

LIG – Low income group; MIG – Middle income group; HIG – High income group

*Ref [58], this model has also been published in Archives of disease in childhood. 2011;96(4):407

Conclusion

The private health sector in India, even though it is heterogeneous and varied in quality, is a potential resource which can contribute to public health objectives. Innovative and effective private-public initiatives are feasible and successful in contemporary India. India’s government has a key and responsible stewardship role in regulating the networking and monitoring of the public-private collaborations. The private sector has a moral and social responsibility to the poor also, and they can meet this with innovative community based health insurance schemes. There is a need for rigorous testing of the proposed model, to provide further evidence of its utility.

[1]. Waters H, Hatt L, Peters D, Working with the private sector for child healthHealth Policy and Planning 2003 18(2):127-37. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Söderlund N, Mendoza-Arana P, Goudge J. The new public/private mix in health: exploring the changing landscape: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research Malta. 2003 [Google Scholar]

[3]. Jindal S, Privatisation of health care: new ethical dilemmasIssues in Medical Ethics 1998 6(3):85-6. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Blumenthal D, Hsiao W, Privatization and its discontents—the evolving Chinese health care systemNew England Journal of Medicine 2005 353(11):1165-70. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Thomas J, Harden A, Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviewsBMC Medical Research Methodology 2008 8(1):45 [Google Scholar]

[6]. Harden A, Thomas J, Methodological issues in combining diverse study types in systematic reviewsInternational Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005 8(3):257-71. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Satpathy S, Public health infrastructure in rural India: challenges and opportunitiesIndian Journal of Public Health 2005 49(2):57 [Google Scholar]

[8]. Rural Health Care System in Indiawelfare Mohaf 2007 [Google Scholar]

[9]. Mahal A, Mohanan M, Growth of private medical education in IndiaMedical Education 2006 40(10):1009-11. [Google Scholar]

[10]. National Rural Health Mission. In: Welfare MoHa, editor. Nirmal Bhawan, New Delhi: Government of India. 2005 [Google Scholar]

[11]. Kumar R, Jaiswal V, Tripathi S, Kumar A, Idris M, Inequity in health care delivery in India: the problem of rural medical practitionersHealth Care Analysis 2007 15(3):223-33. [Google Scholar]

[12]. Gill K. A primary evaluation of service delivery under the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM): findings from a study in Andhra Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Rajasthan. Government of India. 2009 [Google Scholar]

[13]. Satpathy S, Venkatesh S, editors. Human resources for health in India’s national rural health mission: dimension and challenges. Regional Health Forum; 2006: Health Administration Press [Google Scholar]

[14]. Sharma AK, National rural health mission: time to take stockIndian Journal of Community Medicine: Official Publication of Indian Association of Preventive and Social Medicine 2009 34(3):175 [Google Scholar]

[15]. Ananthakrishnan N, Acute shortage of teachers in medical colleges: Existing problems and possible solutionsNational Medical Journal of India 2007 20(1):25 [Google Scholar]

[16]. Bhat R, Characteristics of private medical practice in India: a provider perspectiveHealth Policy and Planning 1999 14(1):26-37. [Google Scholar]

[17]. Viswanathan H, The Rural Private Practitioner. In: Lucius-Kochendörfer G, Peskin B, editorsService Provision for the Poor: Public and private sector coperation 2003 BerlinWorkshop Series:59-65. [Google Scholar]

[18]. Deshpande K, Diwan V, Lönnroth K, Mahadik VK, Chandorkar RK, Spatial pattern of private health care provision in Ujjain, India: a provider survey processed and analysed with a Geographical Information SystemHealth Policy 2004 68(2):211-22. [Google Scholar]

[19]. De Costa A, Saraf V, Jhalani M, Mahadik V, Diwan V, Managing with maps? The development and institutionalization of a map-based health management information system in Madhya Pradesh, IndiaScandinavian Journal of Public Health 2008 36(1):99-106. [Google Scholar]

[20]. Gupta AS, Medical tourism in India: winners and losersIndian Journal of Medical Ethics 2008 5(1):4-5. [Google Scholar]

[21]. National Health Accounts (India)New Delhi: Minsitry of Health and Family WelfareCell NaHA 2001-2002 [Google Scholar]

[22]. Sundar R, Sharma A, Morbidity and utilisation of healthcare services: a survey of urban poor in Delhi and ChennaiEconomic and Political Weekly 2002 :4729-40. [Google Scholar]

[23]. Saradamma RD, Higginbotham N, Nichter M, Social factors influencing the acquisition of antibiotics without prescription in Kerala State, south IndiaSocial Science and Medicine 2000 50(6):891-903. [Google Scholar]

[24]. Bhat R, Regulation of the private health sector in IndiaThe International Journal of Health Planning and Management 1996 11(3):253-74. [Google Scholar]

[25]. Bhat R, Regulating the private health care sector: the case of the Indian Consumer Protection ActHealth Policy and Planning 1996 11(3):265-79. [Google Scholar]

[26]. Chatterjee P, Maharashtra government is told to end doctors’ strikes over poor security in hospitalsBMJ 2013 346(f742) [Google Scholar]

[27]. Moran M, Wood B, States, regulation and the medical profession 1993 BuckinghamOpen University Press [Google Scholar]

[28]. Selvaraj S, Karan AK, Deepening health insecurity in India: evidence from national sample surveys since 1980sEconomic and Political Weekly 2009 :55-60. [Google Scholar]

[29]. India I, The impoverishing effect of healthcare payments in India: new methodology and findingsEconomic and Political Weekly 2010 45(16):65 [Google Scholar]

[30]. Purohit BC, Private initiatives and policy options: recent health system experience in IndiaHealth Policy and Planning 2001 16(1):87-97. [Google Scholar]

[31]. Peters DH, Muraleedharan V, Regulating India’s health services: To what end? What future?Social Science and Medicine 2008 66(10):2133-44. [Google Scholar]

[32]. Mills A, Brugha R, Hanson K, McPake B, What can be done about the private health sector in low-income countries?Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2002 80(4):325-30. [Google Scholar]

[33]. De Costa A, Diwan V, ‘Where is the public health sector?’: Public and private sector healthcare provision in Madhya Pradesh, IndiaHealth Policy 2007 84(2):269-76. [Google Scholar]

[34]. Palmer N, The use of private-sector contracts for primary health care: theory, evidence and lessons for low-income and middle-income countriesBulletin of the World Health Organization 2000 78(6):821-9. [Google Scholar]

[35]. Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, James SL, Hogan MC, Gakidou E, India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluationThe Lancet 2010 375(9730):2009-23. [Google Scholar]

[36]. Mavalankar D, Singh A, Patel SR, Desai A, Singh PV, Saving mothers and newborns through an innovative partnership with private sector obstetricians: Chiranjeevi scheme of Gujarat, IndiaInternational Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics 2009 107(3):271-6. [Google Scholar]

[37]. Developing Healthy villages through Public-Private-People Parternership: A case study. 2008 [Google Scholar]

[38]. De Costa A, Johansson E, Diwan VK, Barriers of mistrust: public and private health sectors’ perceptions of each other in Madhya Pradesh, IndiaQualitative Health Research 2008 18(6):756-66. [Google Scholar]

[39]. Sood SP, Negash S, Mbarika VW, Kifle M, Prakash N, Differences in public and private sector adoption of telemedicine: Indian case study for sectoral adoptionStudies in Health Technology and Informatics 2007 130:257 [Google Scholar]

[40]. Ensor T, Informal payments for health care in transition economiesSocial Science and Medicine 2004 58(2):237-46. [Google Scholar]

[41]. Ramesh B, Nishant J. Governance of private sector corporate hospitals and their financial performance: preliminary observations based on analysis of listed and unlisted corporate hospitals in India. Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad, Research and Publication Department. 2006 [Google Scholar]

[42]. Doherty J, Thomas S, Muirhead D, Health financing and expenditure in post-apartheid South Africa. 1996/97-1998Health EUaNDo 1996 [Google Scholar]

[43]. Sanders D, Chopra M, Key challenges to achieving health for all in an inequitable society: the case of South AfricaJournal Information 2006 96(1) [Google Scholar]

[44]. Hopkins S, Zweifel P, The Australian health policy changes of 1999 and 2000Applied Health Economics and Health Policy 2005 4(4):229-38. [Google Scholar]

[45]. Walker AE, Percival R, Thurecht L, Pearse J, Public policy and private health insurance: distributional impact on public and private hospital usageAustralian Health Review 2007 31(2):305-14. [Google Scholar]

[46]. Nichol B, Hospitals then and now: changes since the start of MedicareAustralian Health Review 2007 31(5):4-12. [Google Scholar]

[47]. Brown L, Barnett JR, Is the corporate transformation of hospitals creating a new hybrid health care space? A case study of the impact of co-location of public and private hospitals in AustraliaSocial Science and Medicine 2004 58(2):427-44. [Google Scholar]

[48]. Sheahan M, Little R, Leggat SG, Performance reporting for consumers: issues for the Australian private hospital sectorAustralia and New Zealand health policy 2007 4(1):5 [Google Scholar]

[49]. Hall J, Incremental change in the Australian health care systemHealth Affairs 1999 18(3):95-110. [Google Scholar]

[50]. Mahal A, Health policy challenges for India: private health insurance and lessons from the international experienceTrade, Finance and Investment in South Asia 2002 New DelhiSocial Science Press:417-76. [Google Scholar]

[51]. Dror DM, Health Insurance for the poor: Myths and realitiesEconomic and Political Weekly 2006 :4541-4. [Google Scholar]

[52]. Dror DM, Radermacher R, Koren R, Willingness to pay for health insurance among rural and poor persons: Field evidence from seven micro health insurance units in IndiaHealth Policy 2007 82(1):12-27. [Google Scholar]

[53]. Devadasan N, Ranson K, Van Damme W, Acharya A, Criel B, The landscape of community health insurance in India: An overview based on 10 case studiesHealth Policy 2006 78(2):224-34. [Google Scholar]

[54]. Devadasan N, Criel B, Van Damme W, Ranson K, van der Stuyft P, Indian community health insurance schemes provide partial protection against catastrophic health expenditureBMC Health Services Research 2007 7(1):43 [Google Scholar]

[55]. Buse K, Walt G, Global public-private partnerships: part I-a new development in health?Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2000 78(4):549-61. [Google Scholar]

[56]. Baliga BS, Raghuveera K, Prabhu BV, Shenoy R, Rajeev A, Scaling up of Facility-Based Neonatal Care: A District Health System ExperienceJournal of Tropical Pediatrics 2007 53(2):107-12. [Google Scholar]

[57]. Singh M, Ethical and social issues in the care of the newbornThe Indian Journal of Pediatrics 2003 70(5):417-20. [Google Scholar]

[58]. Garg P, Public–private collaboration: way forward for survival in resource-poor settingsArchives of Disease in Childhood 2011 96(4):407 [Google Scholar]

[59]. Green A, Gerein N, Exclusion, inequity and health system development: the critical emphases for maternal, neonatal and child healthBulletin of the World Health Organization 2005 83(6):402 [Google Scholar]

[60]. Biswas A, Nandy S, Sinha R, Das D, Roy R, Datta S, Status of maternal and new born care at first referral units in the state of West BengalIndian Journal of Public Health 2004 48(1):21 [Google Scholar]