Therapeutic practice is expected to be primarily based on evidence provided by pre–marketing clinical trials, but complementary data from the post–marketing period are also paramount for improving drug therapy [1]. Drug Utilization Research (DUR) was defined by the WHO in 1977 as “The marketing, distribution, prescription, and use of drugs in a society, with special emphasis on the resulting medical, social and economic implications” [2]. The increased interest in DUR has resulted from recognition of the virtual explosion in the marketing of new drugs, the wide variations in the patterns of drug prescribing and consumption, and the increasing concern about the cost of drugs [1].

For the treatment of psychiatric disorders, a wide array of psychotropic drugs is available [7]. During the past two decades, the development of newer drugs like Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and atypical anti–psychotics have drastically changed the drug therapy protocols.

Methodology

Study design and ethical considerations

A retrospective cross-sectional DUS was conducted after Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) approval. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines were used in the preparation of protocol and the manuscript [8].

Selection criteria

Prescriptions of patients of both sexes and all ages, suffering from a psychiatric illness and started on at least one psychotropic drug, were selected.

Sample size

Six hundred prescriptions were analyzed as per the WHO recommendations on conducting retrospective DUS from medical databases/registries [9].

Study Procedure

The data of the patients attending the Psychiatry OPD, during the period 1st January 2012 to 31st May 2012, was collected from the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) database, thus obviating Hawthorne’s bias, and was recorded in a structured case record form. The sampling frame was fixed as six prescriptions per day, five days a week, during the given sampling period. The six prescriptions were selected as follows:

On day 1, all six prescriptions were chosen from the beginning of the day, on day 2 six prescriptions were chosen from the middle of the day and on day 3, six prescriptions were chosen from the end of the day and so on [9]. In case of OPD holidays, the prescriptions of that day were assigned to the next working day.

Data Analysis

The following data were collected:

Patient details like age, gender and registration number.

Patient diagnosis.

Prescription details like date, number of drugs, names of individual drugs (generic/brand), any Fixed Dose Combination (FDC) prescribed, whether the prescribed drug(s) was available from the hospital pharmacy, dose, dosage form, dosing schedule, and duration of treatment.

The data analysis was done as follows:Assessment of prescription patterns as per the WHO-INRUD drug use indicators [9].

Pattern of psychotropic drug used as per DUS metrics [2]:

The prescribed drugs were classified according to The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) – Defined Daily Dose (DDD) classification.

The Prescribed Daily Dose (PDD) was calculated by taking the average of the daily doses of the psychotropic drugs as the PDD. The PDD to DDD ratio was then calculated.

Cost analysis

Cost of drugs prescribed from the hospital schedule was calculated based on the rate contract available in hospital drug store. Cost of drugs prescribed from pharmacies outside the hospital, was obtained from the Drug Index (DI): April-Jun 2012 [10].

The cost parameters calculated were average total cost per prescription, percentage of average cost due to psychotropic drugs, average cost borne by the hospital, average cost borne by the patient.

For drugs prescribed from outside pharmacies we calculated the price per 10 tablets/capsules (minimum and maximum, as per DI), average monthly cost (minimum and maximum) which was equal to (PDD/ Dose per tablet) x Price per 10 tablets x 3 and Cost Index (CI) (Maximum price / Minimum price)

Statistical analysis

The level of significance was fixed at 5% (p<0.05) with 95% confidence interval. The Chi–Square test was used and all statistical calculations were carried out with Open Epi: A Web-based Epidemiologic and Statistical Calculator [11].

Results

Characteristics of Study Participants

The percentage of female and male patients was 51.8% and 48.2%, respectively. The relative distribution of different psychiatric disorders in different age groups and genders is shown in [Table/Fig-1]. The age range was 10–70 years with the average age being 33.9 years.

Age and gender wise distribution of psychiatric disorders in a sample of prescriptions of patients (n=600) attending the psychiatry outpatient department, Mumbai, India, 1st Jan – 31st May, 2012

| Psychiatric disorder | Age (years) | p–value | Gender | p–value |

|---|

| <20 | 20-40 | 41-60 | >60 | M | F |

|---|

| Schizophrenia and other psychoses (n=180) | 28 | 84 | 54 | 14 | 0.0002* | 102 | 78 | 0.003* |

| Mood disorders (n=238) | 27 | 149 | 44 | 18 | 0.00002* | 119 | 119 | 0.2 |

| Anxiety disorders (n=101) | 32 | 60 | 6 | 3 | 0.00002* | 32 | 69 | 0.0001* |

| Others (n=81) | 39 | 11 | 12 | 19 | <0.0000001* | 35 | 46 | 0.2 |

| Total (n=600) | 126 | 304 | 116 | 54 | - | 288 | 312 | - |

The p value was calculated using the Chi–Square test; * p<0.05.

Pattern of psychiatric disorders

Thirty percent of prescriptions were of schizophrenia, 22% of bipolar mood disorders, 17.7% of depression and 16.8% of anxiety disorders. The disorders like – childhood behavioral disorders, dementia, substance abuse disorders and personality disorders – were grouped as ’other psychiatric illnesses’ (13.5%).

Analysis of Prescription Patterns According to Various WHO/ INRUD Drug Use Indicators [

Table/Fig-2].

Assessment of the prescription pattern, as per various drug use indicators, in a sample of patients (n=600) attending the psychiatry outpatient department, Mumbai India, 1st Jan – 31st May, 2012

| Sr.No. | Drug use indicators | Result |

|---|

| 1. | Average number of drugs per prescription: Mean ± SD | 2.01 ± 1.03 |

| 2. | Average number of psychotropic drugs per prescription: Mean ± SD | 1.79 ± 1.02 |

| 3. | Percentage of prescriptions containing psychotropic FDCs | 135/600 (22.5%) |

| 4. | Percentage of drugs prescribed by generic name | 925/1217 (76.01%) |

| 6. | Percentage of prescriptions with an injection prescribed | 13/600 (2.2%) |

| 7. | Percentage of psychotropic drugs prescribed from the hospital drug schedule | 785/1074 (73.1%) |

| 8. | Percentage of psychotropic drugs actually dispensed from the hospital drug store | 669/1074 (62.3%) |

The 600 prescriptions contained 1217 drugs. Out of these, 1074 were psychotropic drugs. The other drugs commonly co-prescribed were, calcium lactate, vitamin B complex and multivitamins. There was no prescription with more than five drugs. The FDCs prescribed were, trihexyphenidyl hydrochloride 2 mg plus trifluoperazine 5 mg – prescribed to 115 patients and the combination of risperidone 3 mg plus trihexyphenidyl 2 mg – prescribed to 20 patients. The six drugs: trifluoperazine, diazepam, haloperidol, risperidone, carbamazepine and amitriptyline accounted for about 50% of all the drugs prescribed from the hospital drug schedule.

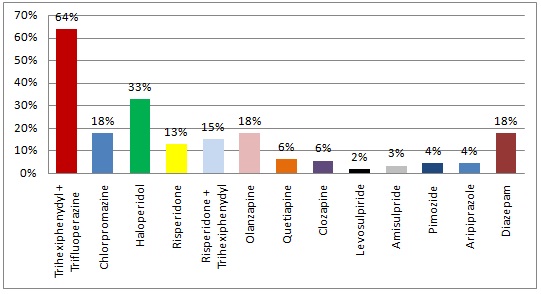

Drugs used in Schizophrenia and other psychoses: (n=180) [Table/Fig-3].

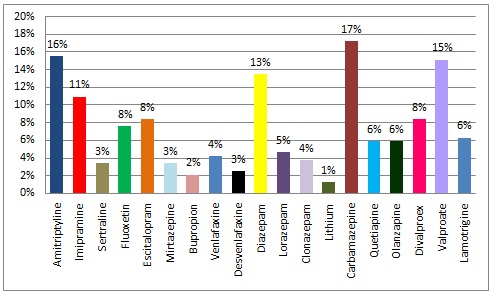

Drugs used in the management of Mood disorders: (n=238) [Table/Fig-4].

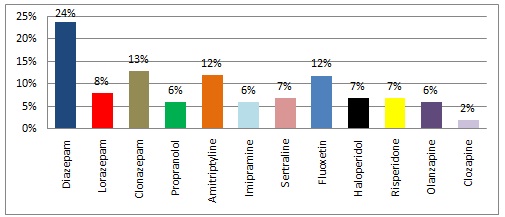

Drugs used in the management of Anxiety disorders: (n=81) [Table/Fig-5].

Percent utilization of drugs in a sample of prescriptions of patients (n=180) suffering from schizophrenia and other psychoses attending the psychiatry outpatient department, Mumbai India, 1st Jan – 31st May, 2012

Percent utilization of drugs in a sample of prescriptions of patients (n=238) suffering from various mood disorders (depression and bipolar disorder) attending the psychiatry outpatient department, Mumbai India, 1st Jan-31st May, 2012

Percent utilization of drugs in a sample of prescriptions of patients (n=101) suffering from anxiety disorders attending the psychiatry outpatient department, Mumbai India, 1st Jan – 31st May, 2012

Pattern of Psychotropic Drug Use as per the ATC/DDD Classification: [

Table/Fig-6].

ATC/DDD classification, PDD values and PDD/DDD ratio of psychotropic drugs prescribed in a sample of patients (n=600) attending the psychiatry outpatient department, Mumbai India, 1st Jan – 31st May, 2012

** For conversion of dose of lithium from mg to mmol the formula used was (16): mg/l × 0.144 = mmol/l × 6.94

| Sr. No. | Drug | ATC code | DDD* (mg) | PDD (mg) | PDD/DDD |

|---|

| 1. | Trifluoperazine | N05AB06 | 20 | 13 | 0.65 |

| 2. | Chlorpromazine | N05AA01 | 300 | 77 | 0.26 |

| 3. | Haloperidol | N05AD01 | 8 | 7.9 | 0.99 |

| 4. | Risperidone | N05AX08 | 5 | 4.5 | 0.9 |

| 5. | Olanzapine | N05AH03 | 10 | 8.5 | 0.85 |

| 6. | Clozapine | N05AH02 | 300 | 193 | 0.64 |

| 7. | Imipramine | N06AA02 | 100 | 73 | 0.73 |

| 8. | Amitriptyline | N06AA09 | 75 | 78 | 1.04 |

| 9. | Sertraline | N06AB06 | 50 | 80 | 1.6 |

| 10. | Fluoxetine | N06AB03 | 20 | 25 | 1.25 |

| 11. | Escitalopram | N06AB10 | 10 | 13.5 | 1.35 |

| 12. | Venlafaxine | N06AX16 | 100 | 78 | 0.78 |

| 13. | Diazepam | N05BA01 | 10 | 6 | 0.6 |

| 14. | Clonazepam | N03AE01 | 8 | 0.75 | 0.09 |

| 15. | Lorazepam | N05BA06 | 2.5 | 2 | 0.8 |

| 16. | Carbamazepine | N03AF01 | 1000 | 673 | 0.67 |

| 17. | Valproate | N03AG01 | 1500 | 1069 | 0.71 |

| 18. | Lithium ** | N05AN01 | 24 mmol | 12.5 | 0.5 |

DDDs mentioned in the table are for the oral route as obtained from the WHO ATC/DDD website 2012 [12].

Cost analysis of prescriptions:

The average cost per prescription was `178 or 3.2 USD, out of which `159 (89.3%) was on psychotropic drugs. The hospital bore 65.2% of the total cost. The drugs prescribed from outside the hospital were analyzed further in terms of their cost as shown in [Table/Fig-7].

Cost analyses of drugs prescribed from outside the hospital to a sample of patients attending the psychiatry outpatient department, Mumbai India, 1st Jan – 31st May, 2012

* The minimum and maximum cost was obtained from the Drug Index: April – June 2012 (13)

| Sr. No | Drugs | Dose per Tablet (mg) | Price per 10 tabs/caps in Rupees* in (₹) | Average monthly Cost (₹) | Cost Index (b/a) |

|---|

| Min (a) | Max (b) | Min | Max |

|---|

| 1. | Risperidone + Trihexiphenidyl | 3 + 2 | 36 | 43 | 216 | 258 | 1.2 |

| 2. | Olanzapine | 10 | 39 | 68 | 117 | 204 | 1.74 |

| 3. | Clozapine | 100 | 45 | 504 | 260.55 | 2918.16 | 11.20 |

| 4. | Levosulpiride | 25 | 57 | 85 | 1026 | 1530 | 1.49 |

| 5. | Pimozide | 4 | 17 | 73 | 51 | 219 | 4.29 |

| 6. | Aripiprazole | 15 | 80 | 82 | 272 | 278.8 | 1.03 |

| 7. | Fluoxetine | 20 | 20 | 44 | 75 | 165 | 2.20 |

| 8. | Escitalopram | 10 | 20 | 79 | 81 | 319.95 | 3.95 |

| 9. | Mirtazepine | 15 | 58 | 73 | 174 | 219 | 1.26 |

| 10. | Bupropion | 100 | 130 | 138 | 780 | 828 | 1.06 |

| 11. | Venlafaxine | 75 | 26 | 80 | 81.12 | 249.6 | 3.08 |

| 12. | Desvenlafaxine | 50 | 78 | 80 | 234 | 240 | 1.03 |

| 13. | Clonazepam | 0.5 | 10 | 25 | 45 | 112.5 | 2.50 |

| 14. | Lorazepam | 2 | 9 | 27 | 27 | 81 | 3.00 |

| 15. | Divalproex | 250 | 33 | 49 | 297 | 441 | 1.48 |

| 16. | Lamotrigine | 100 | 66 | 153 | 144.54 | 335.07 | 2.32 |

| 17. | Quetiapine | 200 | 78 | 103 | 468 | 618 | 1.32 |

Discussion

Profile of study participants

More female patients visited the psychiatry OPD than men. Many studies have reported a similar finding [13–15]. The reproductive age group (20–40 years) accounted for the majority of all the psychiatric disorders, as has been seen in many other studies [16–19].

Prescription Pattern Analysis as per the WHO/INRUD Drug Use Indicators

The average number of psychotropic drugs per prescription was 1.79, which was lower than that found in similar studies, where it ranged from 2.3 to 3 drugs per prescription [20,16,21]. Since, no prescription had more than five drugs, we can say that polypharmacy was avoided. Polypharmacy can lead to poor compliance, drug interactions, adverse drug reactions, under-use of effective treatments and medication errors [22,23].

A large proportion of drugs (76.01%) were prescribed by generic names. The proprietary names were used for the drugs prescribed from outside the hospital. It is a known fact that substitution by generic drugs helps in decreasing the overall cost of therapy and is hence recommended. But there have been concerns in the case of narrow therapeutic index drugs (NTIDs) [24,25]. The USFDA (United States Food and Drug Administration) recommends that the decision should be based on ones professional judgment [26]. Generic substitution can be beneficial, provided, adequate quality control is assured.

In our study, the only injection prescribed was haloperidol decnoate – 50mg/ml – once a month, in a minority of schizophrenics (2.2%) through intramuscular route. Many Indian trials have evaluated the efficacy of depot anti–psychotics in schizophrenia and have found that depot anti–psychotics are useful in the management of schizophrenia in acute phases and also for maintenance treatment [27]. Concerns about the adverse effects and cost-effectiveness of parenteral routes of drug administration, are probably the reason for the low utilization of ’depot injection’ formulation in the psychiatry OPD.

The most commonly prescribed Fixed Drug Combinations (FDCs) was: trifluoperazine (typical anti–psychotic) plus trihexyphenidyl hydrochloride (central anticholinergic) because this combination was available in the hospital pharmacy free of cost. However, this represents an excess use of the anti–cholinergic drug trihexiphenydyl. Most of the antipsychotic drugs (typical) themselves have mild anticholinergic effects. Anti–cholinergic side effects can be debilitating like retention of urine, constipation, attack of angle closure glaucoma, dry mouth etc. Many observers have noted that the addition of anticholinergic medication can exacerbate existing Tardive Dyskinesia (TD), and that discontinuing anticholinergic drugs may improve the condition [28,29]. Based on a number of studies, the WHO has recommended that anti–cholinergics should not be used routinely for preventing extra–pyramidal side effects in individuals with psychotic disorders treated with anti–psychotics but used only for short term in selected cases.

Utilization of drugs from the essential medicines list (Indian & WHO) was very high. The primary purpose of NLEM is to promote rational use of medicines considering the three important aspects i.e., cost, safety and efficacy [30].

Observed Drug Use Pattern in Schizophrenia

The most commonly prescribed drugs were conventional/1st generation anti–psychotics. This is, as per the current recommendations and mainly because they were available in the hospital drug store. For some years, it was believed that the newer/2nd generation drugs were more effective, but that belief is now fading. In addition, the high cost of the atypical/2nd generation antipsychotics is a matter of concern. There have been some important studies which brought to light the finding that 1st generation drugs are as useful as the 2nd generation drugs, with the exception of clozapine which outperforms all [31,32]. In 2009 the American Psychiatric Association (APA) acknowledged the fact that the distinction between first- and second-generation antipsychotics appear to have limited clinical utility [33]. Also, the National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines - 2010, suggested that there it is no longer imperative to prescribe an “atypical” agent as first line treatment [34]. Clozapine may be offered only after primary failure of two antipsychotic drugs.

Diazepam was co–prescribed in about 17.8% of the patients. Benzodiazepines, usually perceived of as quite safe medications, have an addiction potential and can lead to falls, particularly in the elderly. With long term use the adverse effects such as memory impairment, depression, tolerance, and dependence outweighs the benefits. There have been reports of increased mortality among those patients prescribed these medications [35]. The guidelines recommend for their use of short term (maximum, four weeks) or intermittent courses in minimum effective doses [36].

Observed Drug Use Pattern in Mood Disorders

Among the anti–depressants, the Tricyclics (TCAs) were prescribed more than the Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRI). This is contrary to the current recommendations (APA and NICE) in the management of mood disorders [19,37]. The reason being that TCAs were available free of cost from the hospital drug store and the only SSRI on the hospital drug schedule was sertraline due to budgetary constraints. Currently, SSRIs are greatly preferred over the other classes of antidepressants. The adverse-effect profile of SSRIs is less prominent than that of some other agents, which promotes better compliance. The SSRIs are thought to be relatively unproblematic in patients with cardiac disease except citalopram in high doses [38,39].

Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOI) were not prescribed to anyone in our study. The reasons being risk of hypertensive crisis, interactions with other drugs and dietary restrictions for patients on MAOIs [40].

Among the drugs used in bipolar mood disorders, carbamazepine was most commonly prescribed followed by valproate, divalprovex and olanzapine. Lithium was used only in 1.3% patients of bipolar disorder. Studies have shown that patients with bipolar disorder have fewer episodes of mania and depression when treated with mood-stabilizing drugs. Kessing et al found that, in general, lithium was superior to valproate [41]. But because of the low therapeutic index for Lithium (Li+), periodic determination of serum concentrations is crucial [42]. The concern about its narrow therapeutic index and difficulty in obtaining drug levels of lithium, explains the low use of lithium in our center. Many drug utilization studies have also reported a similar finding [43,44]. In contrast to this, in a study conducted by Piparva et al., in Gujarat in 2011, it was found that lithium was used extensively, in about 73% of patients diagnosed with bipolar disorders [16].

According to the NICE guidelines – 2006 [45], for the management of bipolar disorder, lithium, olanzapine or valproate can be considered for long-term treatment. If the patient has frequent relapses, or symptoms that continued to cause functional impairment, switching to an alternative monotherapy or adding a second prophylactic agent (lithium or olanzapine or valproate) should be considered. If a trial of a combination of prophylactic agents proves ineffective, lamotrigine or carbamazepine can be tried.

Observed Drug Use Pattern in Anxiety Disorders

Diazepam was the most commonly prescribed drug for anxiety disorders, followed by Clonazepam, amitriptyline and fluoxetin. The 2011 NICE guidelines for the management of anxiety disorders state that SSRIs or Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) should be offered to the patient first. Benzodiazepines should be avoided and used only for short term in case of crisis [46,47].

Benzodiazepines can be reasonably used as an adjunct in the initial stage while SSRIs are titrated to an effective dose, and they can then be tapered over 4-12 weeks while the SSRI is continued [48].

Alprazolam was not prescribed to any patient suffering from anxiety disorder or otherwise and rightly so because of its higher dependence potential; Alprazolam has a short half-life, which makes it particularly prone to rebound anxiety and psychological dependence [48,49]. Clonazepam has become a favored replacement because it has a longer half-life and empirically elicits fewer withdrawal reactions upon discontinuation.

ATC/DDD Classification and DUS Metrics [Table/Fig-6]

When the PDD/DDD ratio is either less than or greater than one, it may indicate that there is either under or over utilization of drugs. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the PDD can vary according to patient and disease factors. The PDDs can also vary substantially between different countries, for example, PDDs are often lower in Asian than in Caucasian populations. In addition, the DDDs obtained from the WHO ATC/DDD website are applicable for management of conditions of moderate intensity and are based on international data. Thus, the WHO encourages countries to have their own DDD list based on indigenous data.

Cost Analysis

The cost borne by the hospital was almost twice the cost borne by the patient since a large percentage of drugs were prescribed from the hospital pharmacy and this helps improve compliance, especially in the low socioeconomic population [50].

There were no similar studies published, with whom we could compare our cost parameters. Cost of therapy is an important factor in various psychiatric disorders, because of the prolonged treatment. When we calculated the cost of drugs prescribed from outside the hospital, we found that the minimum cost of drug therapy per month was ` 27 for lorazepam and the maximum cost was ` 2918 for clozapine. The CI of desvenlafaxine was the lowest CI (1.03 times) and that of clozapine was the highest (11.2 times). The Cost Index (CI) gives an idea about the difference in cost of the same drug marketed by different companies. This again highlights the need to prescribe generic drugs and choose brands that offer good quality low cost drugs.

The Berkson’s bias [51] may play a role so that the observed prevalence and distribution of various psychiatric disorders may not be generalizable to the entire population. Being a retrospective DUS, we could not measure the consumed daily dose (actual use) and could not assess the comparative clinical effectiveness and adverse effect profile of various psychotropic drugs prescribed.

Conclusion

Schizophrenia was the most common diagnosis followed by bipolar disorder, depression and anxiety disorders.

In Schizophrenia and other psychotic conditions the most commonly prescribed single drug and fixed drug combination were, trifluoperizine and trifluoperizine + trihexiphenydyl, respectively and the least commonly prescribed drug was levosulpiride.

In Bipolar disorders, the most commonly prescribed drug was carbamazepine and the least commonly prescribed drug was lithium.

In Depression, the most commonly prescribed drug was amitriptyline and the least commonly prescribed drug was bupropion.

In Anxiety disorders, the most commonly prescribed drug was diazepam and the least commonly prescribed drug was clozapine.

A major part of the total cost per prescription was borne by the hospital.

Overall, the principles of rational prescribing were followed according to the various drug use indicators mentioned by WHO/INRUD. A few deviations were found from the guidelines (APA and NICE) due to socioeconomic reasons, budgetary constraints and technical difficulties.

We would like to make the following recommendations:

The Hospital Drug Schedule: Need to add more SSRIs.

The practice of using typical antipsychotics as first line should be continued.

Anticholinergics should be used only in selected cases of patients on anti psychotics.

The use of diazepam (volume and duration) should be curtailed.