Case Presentation

A 49-year-old male with a past medical history of bipolar disorder, sickle cell trait and IV heroin, fentanyl and cocaine abuse was admitted to a hospital with fever, headache, toothache, low back pain and a nonspecific facial palsy. The patient reported a habit of injecting a mixture of at least 3 gm/day of heroin mixed with fentanyl, from prescription patches diverted from a medical supply. The patient reported occasional use of intravenous cocaine and an active smoking history of 3 cigarettes per day. He denied alcohol or marijuana use. His last dose of IV drugs was just a few days before admission.

At admission, his white blood cell count was 19,1 k/ul, haemoglobin was 12.2 g/dl, haematocrit was 35.9%, and platelets were 115 k/ul. Alkaline phosphatase was 146 U/L. Gamma glutamyl transferase was 109 k/ul. CRP was 5.9mg/L, ESR was 32mm/hr. CSF cultures from lumbar puncture were negative for bacterial, fungi or viral infections. Head CT and MRI were negative for any acute process. Transthoracic echocardiogram revealed a 0.5 x 0.6 cm vegetation on the medial leaflet of the tricuspid valve, with a strand prolapsing into the right atrium during systole.

On hospital admission day 1, 1/2 blood cultures grew Haemophilus parainfluenzae and a species of Streptococcus. The second bottle grew Actinomyces species. On day 4, 2/4 blood cultures grew Actinomyces species and 2/4 bottles grew a nutritional variant of Streptococcus. On day 7, 2/2 cultures grew H. parainfluenzae. On day 8, 2/4 cultures grew H. parainfluenzae and 2/4 cultures grew Neisseria sicca/subflava in two bottles. On day 9, 2/4 cultures grew Actinomyces and gram positive cocci. Blood cultures were obtained for fungal species, with no growth being reported [Table/Fig-1 and 2].

Blood culture results from the first hospital

| Hosp. Day | Aerobic Culture | Aerobic Gram Stain | Anaerobic Culture | Anaerobic Gram Stain |

|---|

| 1 | Haemophilus parainfluenzae (positive at 33 hours 9 minutes) | Gram positive cocci chains/pairs | Actinomyces species (positive at 16 hours) | Gram positive bacilli |

| 4 | Actinomyces species Nutritionally variant Streptoccus spp. | Gram positive bacilli | Nutritionally variant Streptoccus spp. (positive at 22 hours) | Gram positive cocci in chains |

| 4 | Nutritionally variant Streptoccus spp. Actinomyces | Gram positive bacilli | Nutritionally variant Streptoccus spp. (positive at 23 hours) | Gram positive cocci |

| 7 | Haemophilus parainfluenzae (culture positive at 20 hours) | Gram negative bacilli | No growth | Gram negative rods |

| 8 | Neisseria sicca/subflava (culture positive at 22 hours) | Gram negative diplococci | Neisseria sicca/subflava (positive at 36 hours) | Gram negative diplococci |

| 8 | Haemophilus parainfluenzae (culture positive at 25 hours) | Gram negative bacilli | Haemophilus parainfluenzae (positive at 27 hours) | Gram negative bacilli |

Blood culture results from Carney Hospital

| Patient left against medical advice and then presented to our hospital after 24 hours. The results below are from the second hospitalization. |

|---|

| 1 | Neisseria sicca/subflava (positive in <24 hours) | Gram negative cocci | Neisseria sicca/subflava (positive in <24 hours) | Gram negative cocci |

| Neisseria sicca/subflava (positive in <24 hours) | Gram negative cocci | Neisseria sicca/subflava (positive in <24 hours) | Gram negative cocci |

| Neisseria sicca/subflava (positive in <24 hours) | Gram negative cocci | Neisseria sicca/subflava (positive in <24 hours) | Gram negative cocci |

| 2 | Species type not performed, presumed N. sicca/subflava (positive in <24 hours) | Gram negative cocci | Species type not performed,

presumed N. sicca/subflava (positive in <24 hours) | Gram negative cocci |

| Species type not performed, presumed N. sicca/subflava (positive in 4 days) | Gram negative coccobacilli | No growth | none |

| 3 | No growth | none | Species type not performed, presumed N. sicca/subflava | Gram negative cocci |

| No growth | none | Species type not performed, presumed N. sicca/subflava | Gram negative cocci |

| 4 | No growth | none | Species type not performed, presumed N. sicca/subflava | Gram negative cocci |

| No growth | none | Species type not performed, presumed N. sicca/subflava | Gram negative cocci |

| 5 | Neisseria sicca/subflava (positive in 4 days) | Gram negative cocci | No growth | none |

| 11 | No growth | none | No growth | Gram negative cocci |

| 20 | No growth | none | Prevotella denticola (central line blood culture) | Gram negative rods |

| No growth | none | Prevotella denticola (peripheral blood culture) | Gram negative rods |

The patient was treated with IV vancomycin for 6 days before he left against medical advice. His temperature on discharge was noted to be 102.4F. After leaving the hospital, the patient reported using IV heroin again, and presented to our hospital one day later. On admission, he was noted to have a fever of 102.8°C.

The patient was admitted to the general medical floor, but he soon developed chest pain, dyspnea, hypoxia and diaphoresis. He was transferred to the ICU for monitoring and further management. Physical exam demonstrated crackles at the lung bases, right-sided diffuse chest tenderness and splenomegaly.

Serologies were positive for Hepatitis A, B and C, with a hepatitis C viral load of 1,340,000 IU/mL. Serology for HIV was negative.

Echocardiogram demonstrated 0.5x1.0cm vegetation on the posterior leaflet of the tricuspid valve. CT-chest revealed cavitating nodules in the upper lobes of both lungs, “basilar granulomas” and multiple splenic infarcts, consistent with a diagnosis of septic emboli [Table/Fig-3].

Chest CT demonstrating septic emboli and cavitary lesions

The patient was given IV vancomycin for 6 days at another hospital, then IV gentamicin for 4 days at our hospital, which then was discontinued, and the patient was started on IV ceftriaxone for 22 days. However, he was observed to have daily fever of 104.8°F, with rigors, chills, and diaphoresis, requiring high doses of acetaminophen and ibuprofen and cooling blankets. The febrile episodes would last for a few hours at a time.

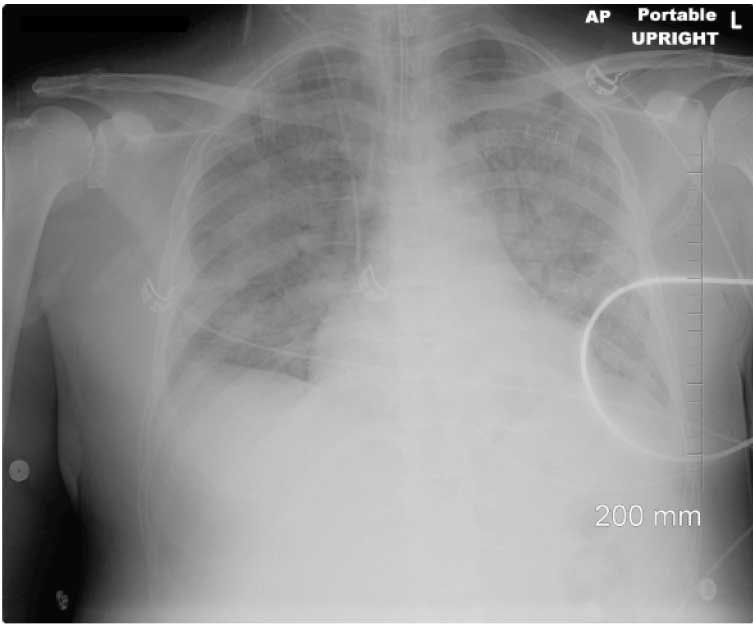

On hospital admission day 13, the patient developed respiratory failure, was intubated and was placed on a mechanical ventilator. Chest X ray demonstrated consolidation of the upper lobes, suggestive of aspiration pneumonia [Table/Fig-4]. Chest X ray, arterial blood gas and laboratory results were also consistent with diagnosis of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). Levofloxacin was added for anaerobic coverage.

Chest x-ray just after intubation

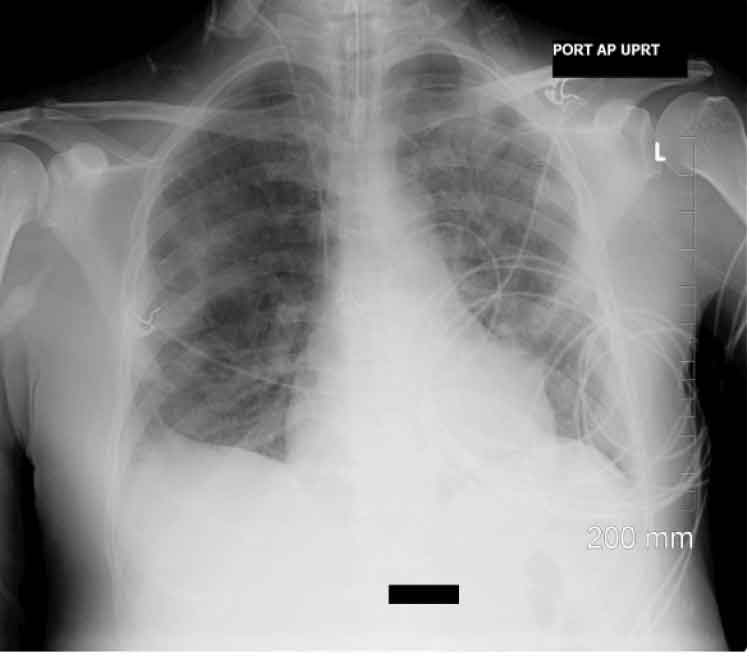

A repeat echocardiogram, showed an increased size of the vegetation on the posterior leaflet of tricuspid valve, now measuring 0.8 x 1.6cm, with moderate tricuspid regurgitation, and markedly elevated pulmonary artery pressure. Repeat chest X–ray was done on day 15 showed improvement following 2 days of levofloxacin therapy [Table/Fig-5].

Chest x-ray following 2 days of levafloxacin therapy

During the hospitalization, the patient developed severe anaemia and thrombocytopaenia, requiring transfusion of 11 units of packed red blood cells and 1 unit of platelets. A Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) panel failed to confirm a diagnosis of DIC. Heparin Induced Thrombocytopaenia (HIT) was considered, but Heparin PF4 Antibody was negative. His anaemia and thrombocytopaenia was considered to be multifactorial.

The patient’s renal function started to deteriorate on hospital

day 14.

Urine complement C3(123 mg/dL) and C4(27 mg/dL), Anti-Ds DNA and Anti-DNAase were within normal ranges. IgG was measured at 3340 mg/dL, IgA at 512 mg/dL, IgM at 205 mg/dL. Cryoglobulins were negative. However, rheumatoid factor was 63 IU/mL and it was thus elevated. The overall picture was consistent with a diagnosis of ATN as well as immuncomplex-mediated proliferative glomerulonephritis, most likely caused by hepatitis C, although post-infectious glomerulonephritis caused by N. sicca could not be excluded. Hemodialysis was begun on hospital day 21 via a femoral catheter.

On hospital day 22, the patient also developed dark skin lesions on his fingers, consistent with features of septic emboli to the skin [Table/Fig-6].

Septic emboli to the skin

The patient failed seven days of spontaneous breathing trials, and on intubation day 8 (hospital day 21), a tracheostomy as well as a Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy (PEG) were placed. Repeat CT scan of chest, abdomen, and pelvis, obtained on hospital day 23, showed worsening bilateral cavitary lesions that were new or slightly larger than those seen in the prior study done on hospital day 13 [Table/Fig-7]. A new 1.0x1.5cm left upper lobe nodular opacity was also noted. Small bilateral effusions and left upper lobe parenchymal opacities with air bronchograms worsened since the previous scan as well.

Chest CT demonstrating worsening bilateral septic emboli and cavitary lesions and mall effusion

An outside hospital was asked to evaluate the patient for possible cardiothoracic surgery, but it declined to do surgery.

Ceftriaxone was discontinued on hospital day 22 and the patient was started on Ciprofloxacin and on Metronidazole. Four days after initiation of Ciprofloxacin, the patient became afebrile. WBCs trended down. The patient’s respiratory status improved and he was able to be weaned off the ventilator machine.

A repeat TTE done on hospital day 31 showed improved systolic function with an EF of 55-60% and a “smaller vegetation” on the tricuspid valve. The tricuspid regurgitation remained moderate in severity. Blood cultures repeated were all negative. The patient’s overall clinical course improved and he was screened for rehab.

Furthermore, after being on haemodialysis for three weeks, the patient’s kidney function returned back to baseline, without the need of any further dialysis.

Discussion

Neisseria sicca/Subflava

Neisseria species are known to cause meningitis, septicaemia, otitis, bronchopneumonia, and genital tract disease [1]. However, N. sicca, a commensal microorganism of the upper respiratory tract, is an exceedingly rare cause of endocarditis. Only 21 cases of N. sicca endocarditis have been described in the literature since 1918 [2]. The most common clinical features of Neisseria species endocarditis include fever, headache, chills, murmur, petechiae, and haematuria [1].

N. sicca endocarditis, in particular, has been associated with prolonged fever, pneumonia, intracranial aneurysms, popliteal aneurysms, hepatic artery mycotic aneurysms, liver abscesses, disseminated disease in the immunocompromised, and fatal embolic phenomenon [3,2,4,5], four of which we encountered in our case. This disease has been associated with IV drug use and it is found in non-IV drug users with carious teeth [3], which were both seen as features in our patient [Table/Fig-8].

Some recent case reports of N. sicca endocarditis

| Reference | Age/Sex | Valve Involved | Organism | Therapy | Complications | Outcome |

|---|

| Aronson et al., [6] | 12 F | Mitral | N. sicca | PCN G | Pulmonary hemorrhage, ARDS, DIC, subarachnoid hemorrhage | alive |

| Sommerstein et al., [7] | 75 F | Aortic | N. sicca | Amox/clav | Cerebellar/lung emboli | dead |

| Debellemaniere et al., [2] | 41 M | Aortic | N. sicca | Cipro, gentamicin | Aortic ring abscess, CHF | alive |

| Present report | 49 M | Tricuspid | N. sicca/subflava, multiple | Vancomycin, ceftriaxone ciprofloxacin flagyl | Septic lung emboli, skin emboli, respiratory failure | alive |

A patient who had been reported previously [6] had many symptoms similar to those of our patient, including very high fever, decreased responsiveness, abnormal mentation, ARDS, progressive anaemia requiring blood transfusions and thrombocytopaenia. Some features of other patients recently reported with N. sicca endocarditis have been shown in [Table/Fig-8].

Haemophilus parainfluenzae

H. parainfluenzae is an established cause of infectious endocarditis, being one of the “HACEK” organisms. It tends to produce vegetations more on the mitral and aortic valves than on the tricuspid valve [8]. It is known to present with prolonged, high fever with rigors, organ dysfunction and severe headache [8,6]. In intravenous drug users with salivary contamination of needles, H. parainfluenzae has been described as presenting with severe endocarditis, with prominent septic pulmonary emboli [9]. Despite its severe course, the mortality is reportedly low [10] [Table/Fig-9].

Case reports of Haemophilus parainfluenzae endocarditis

| Reference | Age/Sex | Valve Involved | Organism | Therapy | Complications | Outcome |

|---|

| Adler et al., [3] | 39 M | Tricuspid | H. parainfluenzae, multiple | Amp, metronidazole | Cardiac surgery, subclavian abscess | alive |

| Patel et al., [11] | 34 F | Tricuspid | H. parainfluenzae, multiple | amp | Pulmonary emboli | alive |

| Nwaohiri et al., [12] | 64 F | Tricuspid | H. parainfluenzae | ceftriaxone | none | alive |

| Christou et al., [13] | 54 F | Mitral | H. parainfluenzae | ceftriaxone | Cerebral emboli | alive |

| Present report | 49 M | Tricuspid | N. sicca/subflava, multiple | Vancomycin, ceftriaxone Ciprofloxacin flagyl | Septic lung emboli,

skin emboli respiratory failure | alive |

Actinomyces

Actinomyces is an exceedingly rare cause of infectious endocarditis. It is associated with systemic emboli to the central nervous system [14]. There have been only 15 reported cases of endocarditis involving Actinomyces species since 1939, including this report [15,11]. Five of the reported patients died of the infection [Table/Fig-10].

Case reports of Endocarditis caused by Actinomyces species11

| Reference | Age/Sex | Valve Involved | Organism | Therapy | Complications | Outcome |

|---|

| Uhr | 24 M | Aortic/Mitral | A. bovis | Sulfathiazole | CNS emboli, CHF | dead |

| Beamer et al., | 55 M | Aortic/Mitral | Actinomyces sp. | none | CNS, renal, GI emboli | dead |

| MacNeal et al., | 39 M | Mitral | Actinomyces sp. | PCN G | CNS emboli | alive |

| Wedding | 37 M | Mitral | Actinomyces sp. | Sulfadiazine | CHF, renal, GI emboli | dead |

| Walters et al., | 43 F | Aortic/Mitral | A. bovis | PCN G | GI emboli | alive |

| Dutton and Inclan | 6 M | Mitral | A. israelii | PCN G | CHF | dead |

| Gutschik | 70 M | Mitral | A. viscosus | PCN G | CNS emboli, CHF | alive |

| Lam et al., | 65 M | Aortic/Mitral | A. israelii | PCN G | none | alive |

| Reddy et al., [17] | 64 M | Aortic | A. pyogenes | multiple | CNS emboli, CHF | dead |

| Hamedka | 81 M | Aortic | A. viscosus | Ceftizoxime | none | alive |

| Huang et al., | 55 F | Mitral | A. meyeri | Amp-Sulb | none | alive |

| Mardis and Many | 38 M | Mitral | A. viscosus | Multiple, PCN G | Cutaneous emboli | alive |

| Oh et al., [14] | 33 M | Tricuspid | A. odontolytica | ceftriaxone | Cavitary lung lesions | alive |

| Cohen et al., [18] | 68 M | Aortic (bicuspid) | A. neuii | Amp, ceftriaxone, gentamicin | Aortic abscess, acute renal failure | alive |

| Present report | 49 M | Tricuspid | Actinomyces sp., multiple | Vancomycin, ceftriaxone ciprofloxacin flagyl | Septic lung emboli, skin emboli, respiratory failure | Alive |

The species found to cause endocarditis include A. israelii, A. bovis, A. viscosus, A. pyogenes, A. meyeri, A. funkei, and A. neuii. Actinomyces species are known to be involved in polymicrobial infections in intravenous drug abusers and they are thought to be caused by saliva-to-needle contact [16]. In recent reports, ceftriaxone and ampicillin have been used successfully to eradicate the organism [15]. In our case, however, the patient’s condition did not improve on ceftriaxone treatment alone.

Conclusion

Infective endocarditis is a life threatening condition with a high mortality rate [19]. Polymicrobial endocarditis carries a mortality rate which has been reported to be greater than 30% [20].

While a vast majority of endocarditis cases are caused by a single organism, polymicrobial endocarditis appears to be increasing in incidence, especially amongst intravenous drug users [17]. Over 50% of these patients will require cardiac surgery for controling the infection or for repairing damaged valves [10].

The polymicrobial infection in our patient was caused by Neisseria sicca, Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Actinomyces species, and Streptococcus viridans. With the exception of S. viridans, these organisms are rare causes of endocarditis, even amongst intravenous drug abusers.

While N. sicca infections remain relatively rare, they have the potential to cause severe diseases with very high mortality. Furthermore, endocarditis caused by this species is known to cause numerous symptoms and complications. In our review of the literature and from our own experience, polymicrobial endocarditis was found to be characterized by severe, prolonged illness requiring intensive care, with mortality rates as high as 90% [17]. Unfortunately, our knowledge on this area is still limited to case reports.

Our patient reported injecting a mixture of heroin and fentanyl. The patient’s heroin dealers would scrape fentanyl off of a prescription fentanyl patch, freeze it, and then mix it with heroin prior to his injecting it. While endocarditis associated with intravenous heroin use has been well documented, this is the only case which has been reported, that involves infectious endocarditis associated with intravenous fentanyl abuse. Clinicians should be aware of the growing trend among injection drug users of using fentanyl in this matter.

Finally, it is s noteworthy that the patient’s condition did not improve on treatment with ceftriaxone. There was insufficient growth of the sample, for testing its susceptibility in vitro, but studies have shown that the species was resistant to ceftriaxone [21]. It is important for clinicians to remember that, although most other oral organisms that cause endocarditis are readily susceptible to this drug, this species is or may be resistant. Indeed, our patient’s condition began to improve shortly after the institution of ciprofloxacin treatment.

[1]. Johnson AP, The pathogenic potential of commensal species of NeisseriaJ Clin Pathol 1983 Feb 36(2):213-23.Review. PubMed PMID: 6338050; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC498155 [Google Scholar]

[2]. Debellemanière G, Chirouze C, Hustache-Mathieu L, Fournier D, Biondi A, Hoen B, Neisseria sicca Endocarditis Complicated by Intracranial and Popliteal Aneurysms in a Patient with a Bicuspid Aortic ValveCase Rep Infect Dis 2013 2013:895138doi: 10.1155/2013/895138. Epub 2013 Feb 5. PubMed PMID: 23476838; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3576735 [Google Scholar]

[3]. Adler AG, Blumberg EA, Schwartz DA, Russin SJ, Pepe R, Seven-pathogen tricuspid endocarditis in an intravenous drug abuser. Pitfalls in laboratory diagnosisChest 1991 Feb 99(2):490-1.PubMed PMID: 1989813 [Google Scholar]

[4]. Jung JJ, Vu DM, Clark B, Keller FG, Spearman P, Neisseria sicca/subflava bacteremia presenting as cutaneous nodules in an immunocompromised hostPediatr Infect Dis J 2009 Jul 28(7):661-3.doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e318196bd48. PubMed PMID: 19483662 [Google Scholar]

[5]. Chung HC, Teng LJ, Hsueh PR, Liver abscess due to Neisseria sicca after repeated transcatheter arterial embolizationJ Med Microbiol 2007 Nov 56(Pt 11):1561-2.PubMed PMID: 17965360 [Google Scholar]

[6]. Aronson PL, Nelson KA, Mercer-Rosa L, Donoghue A, Neisseria sicca endocarditis requiring mitral valve replacement in a previously healthy adolescentPediatr Emerg Care 2011 Oct 27(10):959-62.doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182309e95. PubMed PMID: 21975499 [Google Scholar]

[7]. Sommerstein R, Ramsay D, Dubuis O, Waser S, Aebersold F, Vogt M. Fatal, Neisseria sicca endocarditisInfection 2013 Jan 8 [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 23297179 [Google Scholar]

[8]. Chopra T, Kaatz GW, Treatment strategies for infective endocarditisExpert Opin Pharmacother 2010 Feb 11(3):345-60.doi: 10.1517/14656560903496430. Review. PubMed PMID: 20102302 [Google Scholar]

[9]. Mardis JS, Many WJ Jr, Endocarditis due to Actinomyces viscosusSouth Med J 2001 Feb 94(2):240-3.Review. PubMed PMID: 11235043 [Google Scholar]

[10]. Sousa C, Botelho C, Rodrigues D, Azeredo J, Oliveira R, Infective endocarditis in intravenous drug abusers: an updateEur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2012 Nov 31(11):2905-10.doi: 10.1007/s10096-012-1675-x. Epub 2012 Jun 20. Review. PubMed PMID: 22714640 [Google Scholar]

[11]. Patel A, Asirvatham S, Sebastian C, Radke J, Greenfield R, Chandrasekaran K, Polymicrobial endocarditis with Haemophilus parainfluenzae in an intravenous drug user whose transesophageal echocardiogram appeared normalClin Infect Dis 1998 May 26(5):1245-6.PubMed PMID: 9597274 [Google Scholar]

[12]. Nwaohiri N, Urban C, Gluck J, Ahluwalia M, Wehbeh W, Tricuspid valve endocarditis caused by Haemophilus parainfluenzae: a case report and review of the literatureDiagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2009 Jun 64(2):216-9.doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.02.015. Epub 2009 Apr 18. Review. PubMed PMID: 19376668 [Google Scholar]

[13]. Christou L, Economou G, Zikou AK, Saplaoura K, Argyropoulou MI, Tsianos EV, Acute Haemophilus parainfluenzae endocarditis: a case reportJ Med Case Rep 2009 Jul 16 3:7494doi: 10.4076/1752-1947-3-7494. PubMed PMID: 19830211; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2737790 [Google Scholar]

[14]. Oh S, Havlen PR, Hussain N, A case of polymicrobial endocarditis caused by anaerobic organisms in an injection drug userJ Gen Intern Med 2005 Oct 20(10):C1-2.PubMed PMID: 16191149; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1490230 [Google Scholar]

[15]. Hyvernat H, Pulcini C, Carles D, Roques A, Lucas P, Hofman V, Fatal Staphylococcus aureus haemorrhagic pneumonia producing Panton-Valentine leucocidinScand J Infect Dis 2007 39(2):183-5.PubMed PMID: 17366043 [Google Scholar]

[16]. Martín-Dávila P, Navas E, Fortún J, Moya JL, Cobo J, Pintado V, Analysis of mortality and risk factors associated with native valve endocarditis in drug users: the importance of vegetation sizeAm Heart J 2005 Nov 150(5):1099-106.PubMed PMID: 16291005 [Google Scholar]

[17]. Reddy I, Ferguson DA Jr, Sarubbi FA, Endocarditis due to Actinomyces pyogenesClin Infect Dis 1997 Dec 25(6):1476-7.Review. PubMed PMID: 9431403 [Google Scholar]

[18]. Cohen E, Bishara J, Medalion B, Sagie A, Garty M, Infective endocarditis due to Actinomyces neuiiScand J Infect Dis 2007 39(2):180-3.PubMed PMID: 17366042 [Google Scholar]

[19]. Leone S, Ravasio V, Durante-Mangoni E, Crapis M, Carosi G, Scotton PG, Epidemiology, characteristics, and outcome of infective endocarditis in Italy: the Italian study on endocarditisInfection 2012 40:527-35. [Google Scholar]

[20]. Saravolatz LD, Burch KH, Quinn EL, Cox F, Madhavan T, Fisher E, Polymicrobial infective endocarditis: an increasing clinical entityAm Heart J 1978 Feb 95(2):163-8. [Google Scholar]

[21]. Tanaka M, Nakayama H, Huruya K, Konomi I, Irie S, Kanayama A, Analysis of mutations within multiple genes associated with resistance in a clinical isolate of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with reduced ceftriaxone susceptibility that shows a multidrug-resistant phenotypeInt J Antimicrob Agents 2006 Jan 27(1):20-6.Epub 2005 Nov 28 [Google Scholar]