“Positive psychology,” is a recent method which is being employed in psychological treatment protocols, in an effort to better understanding about happiness, meaning of life, character strengths, and how all these can be developed and enhanced in life to have a better quality of life [1]. Positive emotions promote discovery of novel and creative actions, ideas and social bonds, which in turn, build an individual’s personal resources; ranging from physical and intellectual resources, to social and psychological resources [2]. Positive emotions play a crucial role in enhancing resources and coping in the face of negative events [3]. Subjective well-being and satisfaction with life are important domains of life [4]. Brief training on mindfulness meditation or somatic relaxation reduces distress and improves positive mood states [5]. Meditation is an age-old self-regulatory strategy that is gaining more interest in mental health counsel and psychiatry, as it can reduce arousal states and anxiety conditions [6]. Meditation is considered as a type of mind-body complementary medicine. It can give a sense of calmness, peace and balance that benefits both emotional well-being and overall health. Spending even a few minutes in meditation can restore mental calmness and inner peace [7]. Brahma kumaris Rajyoga Meditation (BKRM) gives a clear spiritual understanding of self and helps one to re–discover the use of positive qualities which are already latent within oneself, this enables to develop strengths of character and to create new attitudes and responses to life [8].

The present study was aimed at assessing the efficacy of BKRM on positive thinking, essential for enhancing self-satisfaction and happiness in life. Studies done by psychologists have identified significant improvement in critical cognitive skills following brief period of mindful meditation. But, there are no studies which have related the effect of Brahma Kumaris Rajayoga Meditation (BKRM) practice on positive thinking and happiness in life. The present study was designed to test the hypothesis that meditation enhances positive thinking and that it is essential for increasing self-satisfaction and happiness in life.

Material and Methods

This study was approved by the ethical committee of Annamalai University Distance Education program, Annamalai University, Tamilnadu, India. Fifty participants [age: 42.95±15.29] selected for this study included (BKRM) practitioners (n=25) and normal healthy non-meditator subjects [not practising any kind of meditation] (n=25). Socio-demographic profile of each participant was collected, as has been shown in [Table/Fig-1]. Regular meditators were selected from BKRM Centres at Manipal and Udupi, India. All the 25 meditators were daily practitioners of Rajayoga meditation at the centres, who undertook similar practices at home as well. The inclusion criteria for selecting these meditators was, a minimum period of 3 months of regular BKRM practice. Non-meditators were healthy subjects who were willing to participate, selected for the study from the general population of Manipal.

Distribution of socio–demographic status of meditators and non-meditators

| Socio-demographic variables | Meditators (n=25) | Non-Meditators (n=25) |

|---|

| Age (mean±SD) | 48.68±13.77* | 36.96±11.98 |

| Gender n(%) | | |

| Male | 10 (40) | 15 (60) |

| Female | 15 (60) | 10 (40) |

| Marital Status n(%) | | |

| Unmarried | 7 (28) | 8 (32) |

| Married | 18 (72) | 17 (68) |

| Education n(%) | | |

| Non-graduates | 11 (44) | 10 (40) |

| Graduates | 14 (56) | 15 (60) |

| Employment status n (%) | | |

| Unemployed | 11 (52) | 10 (40) |

| Employed | 14 (48) | 15 (60) |

| Economic Status n(%) | | |

| No Income | 8 (32) | 10 (40) |

| Income | 17 (68) | 15 (60) |

SD, standard deviation; NA, not applicable. *P<0.05

Rajayoga Meditation

Rajayoga meditation is one of the training courses of Rajayoga Education and Research Foundation of Brahma Kumaris World Spiritual University (BKWSU), a Non-Governmental Organization [NGO] that has consultative status with UNO, UNICEF and WHO [9].

During Rajayoga Meditation, subjects sit in soul consciousness with their eyes open, and with their gazes fixed on a meaningful symbol (a point of light which is considered as Supreme Soul).The mental connection between the soul and Supreme Soul or the remembrance of the Supreme Soul by the soul is called as Rajayoga. Stability in the Soul-consciousness and God-consciousness will bring peace and bliss to the soul [10] .

This meditation is practised in four stages: [11]

Initiation: Comfortable, quiet, sitting posture with eyes open, relaxing the body and mind.

Meditation: A connected series of pure and positive thoughts that produces the fuel for inner journey of the soul.

Concentration: In this stage, world thoughts cease without difficulty, as the mind becomes fascinated with its own reality and the presence of Supreme Being becomes evident.

Realization: Realization of peace and happiness of mind, experienced as bliss.

Psychological Test Tool

In this study, Oxford Happiness Questionnaire (OHQ) was used to measure the self-reported happiness status. It is being widely used by psychologists and sociologists as a tool for assessing happiness status. OHQ is a uni-dimensional scale with 29-items, designed to measure the happiness status. It is a reliable and valid questionnaire [12]. It employs a 6 point Likert-type format of response, from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree, to measure self-reported happiness score and self-satisfaction score OHQs filled out by all subjects were collected and the mean score for the 29 items was calculated. The lowest possible score was 1 and the highest was 6. Based on the mean score, the ‘unhappy to happy state of mind’ can be interpreted. In this study, mean scores of 4 or >4 were considered as representing happy state and those <4 were considered as representing unhappy state. Further, the items which represented self-satisfaction [Table/Fig-2] of the subjects were selected and the average score of self-satisfaction was compared between meditators and non-meditators.

Comparisons of happiness score, happiness status and self satisfaction between meditators and non-meditators

| Groups (n-50) | Happiness score (mean ±SD) | Happiness status | Self-Satisfaction¶ (mean±SD) |

|---|

| Unhappy n(%) | Happy n(%) | |

|---|

| Meditators(25) | 4.66±0.39** | 1(4) | 24(96)* | 4.80±0.59** |

| Non-meditators(25) | 3.98±0.41 | 11(44) | 14(56) | 4.09±0.53 |

¶ Self-Satisfaction items in Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 14, 17, 22, 24, 29.

SD, standard deviation. *p<0.05, **p<0.001.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics and testing of hypothesis were used for the analysis by using R v2.15.2. The associations between the different variables were tested using the Chi-square test and strength of the relationship was tested using logistic regression. Student t-test was used for the comparison of the mean happiness scores and self-satisfaction scores.

Result

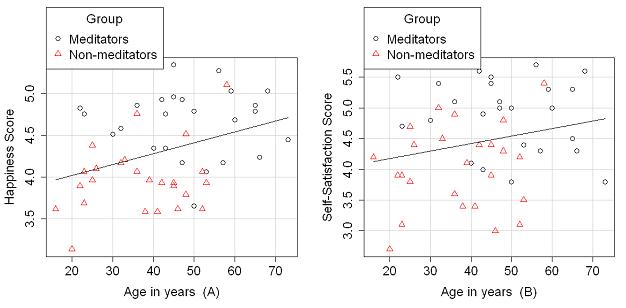

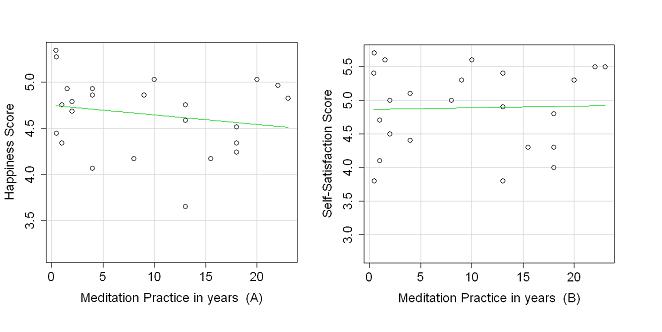

In the present study, no significant difference was found in socioeconomic status between meditators and non-meditators, as has been shown in [Table/Fig-1]. The mean happiness scores and happiness status were compared between meditators and nonmeditators, as has been shown in [Table/Fig-2]. Mean happiness scores of meditators were significantly higher (t=5.88,df = 48, p‹0.001) as compared to those of non-meditators.Significantly more meditators were in happy status as compared to non-meditators c2 (Fisher′s exact test) 10.97, 2-tailed p‹0.05), which indicated that meditators [24(96%)] were happier than non-meditators [14(56)]. Additionally, meditators expressed significantly higher mean self-satisfaction scores(t=4.47, df=48, p ‹0.001) as compared to non-meditators, as has been shown in [Table/Fig-2]. No positive or negative correlation was found between happiness scores (r = -0.04205, 95% CI; -0.4301 – 0.3591, p = 0.8418) and selfsatisfaction scores (r = -0.1955, 95% CI; -0.5483 - 0.2165, p= 0.3491) of meditators as well as happiness scores (r = 0.2840, 95% CI; -0.1252 - 0.6107, p = 0.1688) and self-satisfaction scores (r = 0.1578, 95% CI; -0.2533 - 0.5205, p = 0.4514) of non-meditators in relation to their age, as has been shown in [Table/Fig-3]. The years of meditation practice also did not correlate with happiness score (r = -0.1992, 95% CI; -0.5510 – 0.2128, p = 0.3398) as well as with self- satisfaction score (r = 0.03078, 95% CI; -0.3689 – 0.4209, p = 0.8839) in meditators, as has been shown in [Table/Fig-4].

Correlation of age with happiness score (A) and self-satisfaction score (B) in both meditators and non-meditators. Note the higher distribution of both self-satisfaction and happiness scores in meditators through aging

Correlation of number of years of meditation practice among meditators with their happiness score (A) and self-satisfaction score (B).

Discussion

A positive mind anticipates happiness, joy, health and successful results [13]. Gable stated that communicating personal positive events has an impact on the person, for increasing daily positive effects and well-being [14]. Self-focus on positive self-aspects and following positive events were related to lower negative effects [15]. The short-term effect of positive reappraisal could be helpful for youth experiencing difficulties in managing negative effects [16]. Studies have shown that having positive emotions helped people to come out of depression, following aftermath of any crisis in life [17] and that these positive emotions helped in providing a broad mind-set [2]. Positive behaviour recognition is especially important during adolescent development, to cultivate moral reasoning and social perspective thinking on various social systems [18]. Positive thinking helps with stress management and in overcoming negative self-talk [7]. Levy reported in his aging studies, that older individuals with more positive self-perceptions had better functional health than those with more negative self-perceptions of aging and that they lived 7.5 years longer. This advantage remained after age, gender, socio–economic status, loneliness, and functional health were included as covariates [19, 20]. Similarly, results of the present study suggested that practice of BKRM at any age enhanced positive thinking and that it provided happiness in life.

Diener described that positive and negative feelings were associated with fulfillment of psychological desires [21]. Happiness is not simply a matter of desire satisfaction but of personal well–being or life satisfaction as well [22]. In the present study, meditators had significantly highest scores on self-satisfaction, suggesting that BKRM enhanced personal well-being and it thus, expressed a more self-satisfied life.

Happy people have a functioning emotion system that can react appropriately to life events [23]. Research psychologists, Matthew A. Killingsworth and Daniel T Gilbert of Harvard University reported in 2012, that “the ability to think about what is not happening is a cognitive achievement that comes at an emotional cost” and people who achieve this kind of mindfulness are happier [24]. Studies have shown that brief periods of mindfulness meditation intervention were effective in reducing pain ratings and anxiety scores and that they increased mindfulness skills [25]. It was observed that just 4 days of meditation training could enhance the ability to sustain attention, which was usually reported in long-term meditators. Similarly, in the present study, meditators scored significantly higher in happiness scores than non-meditators, suggesting that BKRM helped in achieving mindfulness which elevated them to happier emotional states, irrespective of the period of meditation experience.

Limitations

The sample size was limited to n=25, since the available regular meditators from Manipal and Udupi BKRM Centres were only 25 in number during our study period from july to september 2012.

This study did not have adequate representation of samples from different socio-demographic and economic strata. Larger sample sizes from both the groups, which belong to different socio-demographic and economic strata, need to be studied, to analyze their effects on self-satisfaction and happiness in life.

Conclusion

Happiness is associated with multiple benefits, including better health. BKRM helps in significantly increasing self-satisfaction and happiness in life by enhancing positive thinking. Irrespective of age and years of short-term or long-term meditation practice, enhanced positive thinking increases self-satisfaction and happiness in life.

SD, standard deviation; NA, not applicable. *P<0.05