There are an estimated 23.9 lakh people living with HIV/AIDS in India with an adult prevalence of 0.31 percent in 2009. HIV Counseling and Testing Services were provided to 106 lakh persons including 45.9 lakh pregnant women during 2010, out of which 12,429 pregnant women tested HIV positive. In Southern India, the prevalence of HIV positive was 1% among antenatal mothers. Tamil Nadu comes under group I high prevalence state, as the prevalence of HIV infection in antenatal mothers is below 1% but above 5% in high risk group (HRG). In Tamil Nadu, 22 districts come under group A (1% prevalence in ANC and 5% prevalence in HRG) and 5 districts come under group B (<1% in ANC and 5% in HRG) [1]. Tamil Nadu State AIDS Control Society (TANSACS) was established in 1993 to control and prevent the spread of HIV / AIDS. TANSACS was the first AIDS Control Society formed in the country. It provides a comprehensive, low cost PPTCT programme of short-term preventive medicine and treatment for the mother as well as the baby by offering safe delivery practice, safe infant feeding practice, counselling and support services. Tamil Nadu’s PPTCT programme is recognised by NACO as the model program for the entire country, with 10.3 lakh (in 2009) pregnant women covered under the programme and 91% (in 2009) of the Mother-Baby pair were administered Nevirapine [2].

Mostly, women are diagnosed as HIV positive during pregnancy as pregnant women attending antenatal clinic are taken as proxy or representative for general population. All antenatal mothers are counseled for HIV testing and if found positive, they are referred to the nearest Anti–Retroviral Treatment (ART) center. However, antenatal, intra-natal and post–natal services are supposed to be provided as for HIV negative mothers. Discrimination against HIV positive patients is alarmingly common in the health care sector. As in other settings, individuals with HIV in India suffer from stigma and discrimination that affect their access to health care, testing, disclosure, treatment adherence and prognosis [3]. A study in 2006 by UNDP found that 25% of people living with HIV in India had been refused medical and surgical treatment on the basis of their HIV positive status [4]. Negative attitudes of health care staff have generated anxiety and fear among many people living with HIV and AIDS and as a result, many keep their HIV status a secret. Antenatal period in HIV positive mothers is a critical period to make them accept Prevention of Parent to Child Transmission (PPTCT), enrolment in HIV care and ART services. The purpose of this study was to explore the difficulties faced by HIV positive mothers of rural areas in Tamil Nadu and the discrimination from health care providers, which act as barrier in accessing intra-natal services by these women.

Material and Methods

This is a descriptive, qualitative study of PPTCT services for pregnant HIV-infected women in the Gingee Block of Tamilnadu.

Study Setting

Gingee Block of Tamilnadu is situated between hills and forests (Gingee group of hills and Muttukadu), 40 kms from Villupuram district headquarters. Public transport facility is not available for all villages; some can be reached only by walk for about 3-4 kms. It has 60 village panchayats and two town panchayats with a population of 1,67,650. The main occupation of the people living here is agriculture and construction labour (mason). Public health infrastructure in this block providing free health care services consists of one Community Health Centre (CHC) in Sathyamangalm, one Taluk Hospital in Gingee Town and four additional Primary Health Centres (PHCs at Ananthapuram, Gengavaram, Nallanpillai and Ottampattu). Antenatal care is provided mainly at the PHCs. Normal deliveries are conducted at the PHCs, while referrals are made to the CHC, Taluk Hospital and District hospital, tertiary centre (JIPMER) and the Government Hospital (GH) in Pondicherry (neighbouring district), both providing referral and all services free of charges.

TANSACS established Integrated Counselling and Testing Centres (ICTC) in all CHCs from June 2006. ICTC facilities were available at Taluk hospital in Gingee town, CHC, Sathyamangalm and District hospital, Villupuram. All the antenatal mothers were motivated and screened for HIV mostly in ICTC of CHC, Sathyamangalam and also in camps like ‘Varumunkappom’ (‘Prevention’ in the local language), implemented by Tamil Nadu State Government. ART services were provided at the District Hospital Villupuram; while CD4 count testing, counseling to HIV/AIDS patients and other welfare schemes by the Government (widow pension, divorce’s pension etc) were also provided to the People living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA).

Procedure

All HIV positive mothers and their children, residing in Gingee Block of Tamil Nadu and detected to be positive between June 2006 and May 2010 were the subjects for this study. Socio-demographic details and data on treatment compliance of these subjects and other co-morbid conditions like tuberculosis were collected from the registers maintained at ART center in Villupuram. Issues regarding problems faced by HIV positive mothers in accessing intra–natal services were included in the interview guide. The lady Out Reach Worker (ORW) under the District Project Manager was also involved in data collection. There were 21 mothers who were identified to be HIV positive during this period. Interviews were conducted after obtaining informed consent from the subjects. The audio-taped interviews were transcribed and then translated into English, and analysed for content. The study protocol was cleared by the Institute Research and Ethics committees.

Results

Majority (67%) of the mothers were less than 30 years of age [Table/Fig-1]. Most women (71%) had education upto middle school level while 19% were illiterate. Five of the 21 women were house wives and rest were agricultural laborers, mason coolies or housemaids. The per capita income per month was below Rs.959 per month for 76.1% of subjects.

Socio–demographic background of HIV positive mothers in this study (n=21)

| Variables | n=21 | % |

|---|

| Age | 20–24 years | 6 | 29% |

| 25–29 years | 6 | 38% |

| 30–34 years | 4 | 19% |

| 35–39 years | 3 | 14% |

| Education Status | Illiterate / No School | 4 | 19.1% |

| Middle School (up to 8th Std) | 11 | 52.3% |

| High School (9th and 10th) | 5 | 23.8% |

| Higher Secondary | 1 | 4.8% |

| Social Class -Per capita / Month | V below 480 | 7 | 33.3% |

| IV 480–959 | 9 | 42.7% |

| III 960–1799 | 1 | 5.0% |

| Present income not known | 4 | 19.0% |

Antenatal Care Services

All 21 mothers received (100%) full antenatal care at their PHCs and Taluk Hospital including Tetanus Toxoid vaccination. In this study 13 (62%) of them were identified to be HIV positive in the CHC, Sathyamangalam, 7 (33.3%) in Taluk Hospital and one in the District Hospital. Out of 21 mothers, two did not give consent and hence in-depth interviews were conducted at the homes of the rest 19 women.

Place of Delivery

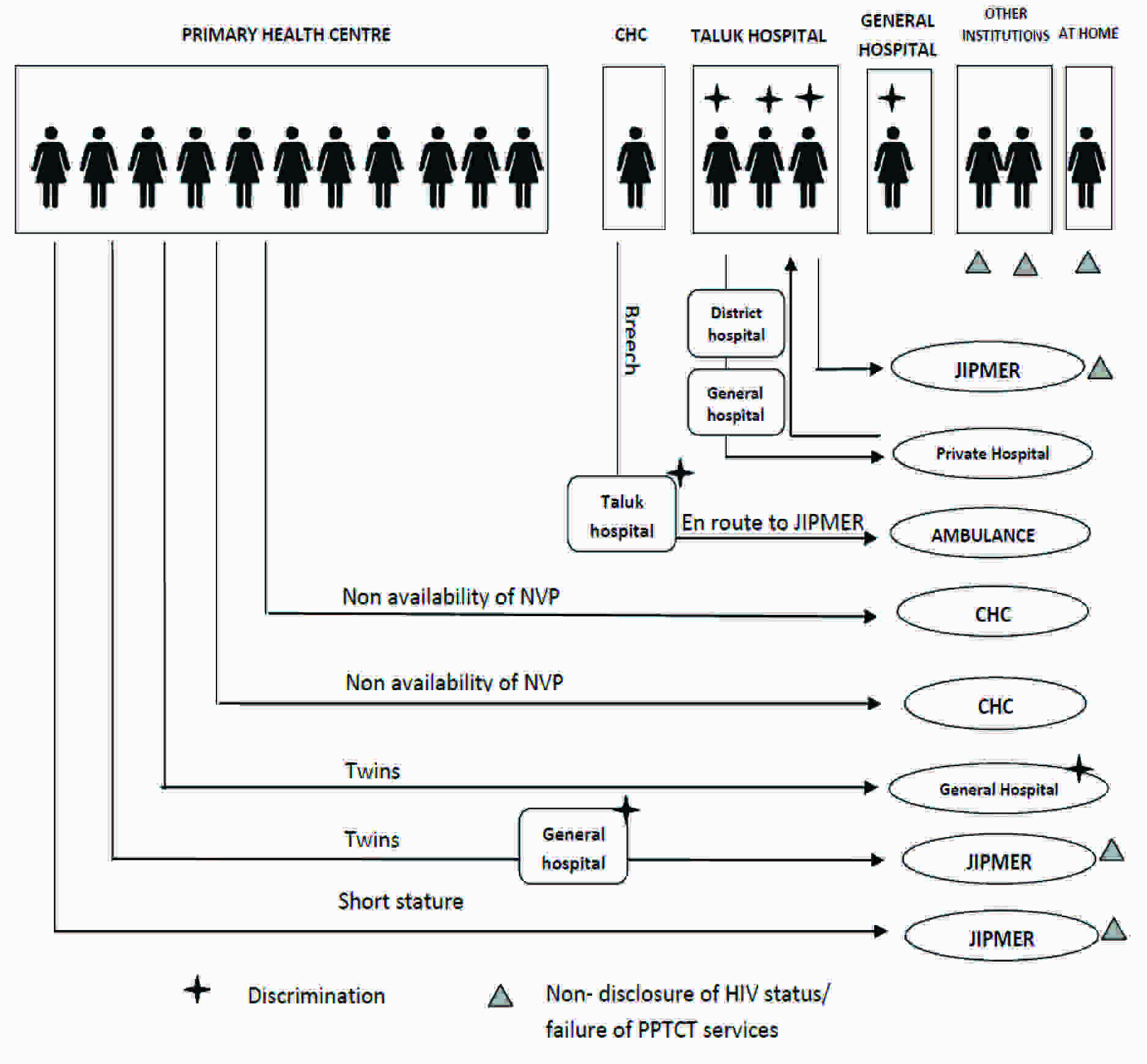

During their antenatal checkups identification of institution for delivery was made by Doctors, Village Health Nurses and counselor of ICTC. Sixteen (76%) of them were advised to undergo delivery in their area PHCs, whereas 3 of them were referred to higher institution i.e. District Hospital because of their high risk conditions like breech, short stature and twin pregnancy. Fourteen of the 19 mothers chose the health facility based on the advice of the health care providers, five went to different centre for their delivery.

Intra–natal Care Services

During intra-natal period in all these facilities, monitoring and delivery care were given for 15 women (79%) by Staff Nurses and for four women (21%) by Doctors. From the experiences of these 19 mothers, the problems that emerged to be affecting the HIV positive pregnant women accessing intra-natal care were as follows; eleven out of 19 subjects faced difficulties and discrimination during intra natal care in different levels of health institutions [Table/Fig-2]. Seven mothers felt offended due to the rude comments and behaviour of the health care providers. Five of these subjects were monitored only by asking questions and were not examined per abdomen or per vaginum.

Experiences of HIV positive mothers during Intra-natal period (n=19)

Experiences at the Primary Health Centres and Community Health Centre

Out of 11 women who approached the PHC for their delivery, one was referred to a tertiary centre, the indication being short stature (contracted pelvis), while two mothers were referred for indication of pregnancy with twins. Two women were referred to CHC, Sathyamangalam due to the non availability of Nevirapine tablets and drops at the PHCs. One mother went directly to CHC as advised by the ORW during her antenatal period, for possible breech presentation.

One lady who went to CHC narrated her experience as painful. In the CHC, the Staff Nurse on duty hesitated to examine and scolded her saying, “Why did you come here as per the advice of the PHC staff? Why didn’t you go to JIPMER Pondicherry (tertiary centre)?” As the woman waited, duty changed and the next duty Staff Nurse conducted normal delivery with the help of the ORW without any problems.

Unnecessary Referrals

All three subjects, who had gone directly to Taluk Hospital, Gingee for delivery, faced problems. One of these subjects was referred to District Hospital, Villupuram for LSCS stating the reason as prevention of transmission of HIV to her infant. But from the District Hospital she was again referred to GH Pondicherry stating, that they were not performing LSCS for HIV patients. After reaching GH Pondicherry, she was made to wait for a long time without any examination. Because of all these referrals she was frustrated and came back to a private hospital in Gingee. But due to the efforts of the District Project Manager and ORW, she was again brought back to Taluk Hospital, Gingee where she had a normal delivery. By then she had faced repeated referrals and transfer from one hospital to another hospital 4 times during the labour.

Another subject, who was referred from CHC to Taluk Hospital Gingee for breech delivery, was referred again from there to JIPMER without any examination. She delivered a dead born baby in the ambulance itself, conducted by Staff Nurse deputed from CHC.

Discrimination in Providing Care

Out of three subjects who accessed a tertiary care facility (General Hospital) for delivery, two were referred from their area PHC for high risk status (pregnancy with twins) during the antenatal period. They were monitored during delivery, but they were treated badly. One mother said “I was given a place adjacent to the toilet before and after the delivery of my twin babies. Both the infants died within 2 days of birth. Because of these incidents and discrimination in care by the health care providers, I preferred JIPMER for my two subsequent deliveries, without disclosing my HIV status.” Another mother with twin pregnancy reported, “The ANM and staff nurse threw the records on my face and asked me to go to JIPMER for delivery. During that time my membranes ruptured. So I went to JIPMER, throwing my records (in frustration) and delivered there without disclosing my HIV status.”

Failure of Prevention of HIV Transmission

All the three subjects who received intra-natal care at JIPMER Pondicherry did not disclose their HIV status, owing to their bad experiences at other centres, and therefore Nevirapine tablets and drops were not given to the mother and the babies. One of these mothers disclosed her HIV status during the postnatal period and hence the baby received NVP drops. The twin infants delivered in JIPMER died during their third and fifth month because of respiratory infection and diarrhea respectively. In JIPMER all antenatal cases are screened for HIV routinely, but mothers not receiving antenatal care at this centre and seeking emergency services during labour are not tested for HIV. Two subjects who preferred other institutions outside the block area did not disclose their HIV status and delivered without receiving Nevirapine.

Discussion

In this rural block of Villupuram district in Tamil Nadu, India, all the HIV positive pregnant women between June 2006 and May 2010 were from the lower socio-economic strata. Though all these subjects received antenatal care and advise on the place of delivery, most of them faced discrimination and difficulties during the intra-natal period. In a study among women accessing PPTCT services in the rural Northern Karnataka, HIV positive women consistently expressed that discrimination was an important barrier for access to health care in the medical facility. HIV positive mothers had experienced refusal for treatment, abusive behavior, moral judgment and lack confidentiality by health staff [5].

Similar are the experiences of women in the African countries. Operational research results of HIV/AIDS related stigma, fear and discriminatory practices among health care providers in Rwanda showed that 76.4% of them were discriminatory towards HIV positive patients in hospitals and health centers [6]. During labour and delivery, 41.7% of providers discriminated against HIV positive mothers. About 9% of providers refused to provide care to a patient with HIV / AIDS in Nigeria, in a qualitative survey [7]. In Bangladesh, much higher percentage of the staff nurses (80%) and physicians (90%) exhibited discriminatory behaviour with the HIV positive individuals [8]. HIV related stigma and discrimination remains an economical barrier to effectively fighting the HIV and AIDS epidemic [9].

Unnecessary referrals were made for these women from rural areas, in some cases citing the need for LSCS for HIV positive pregnant women. In a resource-limited setting, several interventions to reduce mother to child transmission may prove difficult to implement; Cesarean delivery is often not safely available [10]. LSCS in HIV patients need not be insisted in resource poor settings, since perinatal transmission rate to child can be reduced to below 5 to 8% with measures like ART to the mother during pregnancy and delivery, Nevirapine to new born, avoidance of invasive procedures during pregnancy and avoidance of breastfeeding. Moreover studies from the region have suggested that safe vaginal delivery may be an acceptable solution for prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV in mothers on Nevirapine and is more cost effective than elective Caesarian section [11].

Fear of discrimination and specific personal experience with abuse and denial of services led a few mothers to hide their HIV serostatus (or non-disclosure) during the intra natal period. This results in non-provision of PPTCT services to the subjects and also increased risk to the health staff at these health centres or institutions.

The negative attitude of the health care providers towards HIV positive pregnant women could decelerate the progress in control of HIV/AIDS, as barriers to health care services. The long term implications on the control programme may be in the form of avoidance of HIV testing and therefore avoidance of ART by the women. Facilities should have sufficient equipments, instruments and information so that health workers can carry out universal precautions and prevent exposure to HIV. Multiple approaches is needed to reduce or eliminate discrimination among health care providers starting from Sanitary workers, Maternity Assistants, Staff Nurse up to Doctors in different levels of health facilities like sub centre, Primary Health Centers, Taluk Hospital, District Hospital and Institutions. Research has shown that a multi-component approach is needed to reduce stigma and discrimination and increase access to essential PPTCT services in India through acknowledging the institutional/cultural roots of the problem, examining HIV-related laws and policies, normalizing HIV testing, improving quality of PPTCT services, better training of health care providers in medical ethics and professionalism and community education strategies [5].

Conclusion

Findings of this research suggest that HIV positive pregnant women experience stigma and discrimination and unnecessary referrals during the intra-natal period, which makes delivery of PPTCT services a challenging issue. Discrimination against HIV positive mothers is a high risk not only to the mothers, babies, but also to the health care providers. There is a pressing need to improve access to quality PPTCT services for HIV-infected pregnant women in India, especially during the intranatal period.