Mental and behavioural disorders accounts for 12% of the global burden of disease. The global prevalence of mental and behavioural disorders among the adult population is estimated to be 10% and contributed to four of the ten leading causes of disability [1]. These disorders account for low productivity and poor health of the people. Among mental disorders, depression is one of the most common disorders which presents with a variety of symptoms. More than 150 million persons suffer from depression at any point of time in the world [2]. Depression is the leading cause of disability as measured by Years Lived with Disability (YLDs) and was 4th leading contributor to the global burden of disease in 2000. By the year 2020, depression is projected to reach 2nd place of the ranking of Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) calculated for all ages and both sexes. Today, depression is already the 2nd cause of DALYs in the age category 15-44 years for both sexes combined [3]. The lifetime prevalence of depression is 12.1% [4]. Depression accounts for 5% of the total burden of disease from all causes [5]. A large population-based study from South India reported overall prevalence of depression to be 15.1% after adjusting for age using the 2001 Indian census data [6].

Psychiatric disorders are commonly reported in hospital setting also. 25 to 33% of the patients treated in primary care setting have a mental disorder [7]. Depression, anxiety and alcohol use are the commonest disorders in a primary care setting, contributing to nearly 20% of the caseload [1]. But only a small percentage of these is recognised and treated [8]. Studies have shown that up to half of the patients seen by primary care physicians remain unrecognised and thus untreated [9]. Different Indian studies have reported prevalence of depression in medical out patients ranging from 4.3% to 39.3% [10, 11]. However, the data is not adequate on prevalence of depression in rural hospitals. Keeping all these aspects in view, this study was carried out with an objective to find out the prevalence of unrecognised depression among outpatient attendees in a rural hospital in Delhi, India and its socio demographic correlates.

Material and Methods

Study design, participants and sampling technique

This was a hospital based cross sectional study conducted in Maharishi Valmiki Hospital, Pooth Khurd Village, a 150 bedded secondary level of health care institution situated around 30 km from Maulana Azad Medical College, New Delhi, India. Monthly adult patient load is approximately 36,000. The study was conducted over a period of 60 working days from February to April 2012. In the study, adult patients who came to seek medical care for non- psychiatric morbidities constituted the study population. Sample size was calculated on the basis of a previous study in which prevalence of unrecognised depression was 20% [12]. Taking power of the study to be 80% and α error 5% with 95% confidence interval, the sample size came out to be 385. A total of 395 patients were included in the study. Number of patients from an Out Patient Department (OPD) was taken in proportion to the size i.e. maximum patients use to come in Medicine OPD, thereby maximum number of patients were also taken from the same OPD and so on. Patients coming out from a particular OPD were selected by systematic random sampling method.

Methodology

There is no separate psychiatric OPD. It is assumed that doctors in other OPDs can make psychiatric diagnosis or refer the patient to psychiatrist mentioning their probable diagnosis. Patients were taken from non-psychiatric OPDs i.e. Medicine (42.8%), Orthopaedics (12.2%), Obstetrics and Gynaecology (11.1%). Dermatology (10.1%), Otorhinolaryngology (ENT) (9.6%), Surgery (8.6%) and Ophthalmology (5.6%). Adult patients coming out from an OPD after consultation were than interviewed. The patients were asked about the symptoms of depression in the past 14 days. Patients were diagnosed to be having depression if their score exceed the cut off level of using Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME MD) scale. Patients were also asked about the difficulty level, the problems had posed to their day to day activities if they had checked off any one of the 9 items in the PRIME MD scale. It was scaled as “not difficult at all”, “somewhat difficult”, “very difficult” and “extremely difficult”. Those patients who were found to be suffering from depression after the interview were referred to psychiatrist for further management. Those patients who were already diagnosed to be suffering from depression were also asked about their treatment history.

Study tool

Data was collected by using a predesigned, pretested questionnaire which included socio-demographic profile i.e., age, gender, education, occupation, family type etc, complaints for which patients seek help, diagnosis made by the consulting doctor, presence of any chronic disease and time spent by the doctor in the consultation. Depression was diagnosed by using PRIME MD, Patient Health Questionnaire-9, (PHQ-9). PRIME-MD is an instrument developed and validated in the early 1990s to efficiently diagnose five of the most common types of mental disorders presenting in medical populations: depressive, anxiety, somatoform disorders, alcohol, and eating disorders [13]. In its initial use, it was noticed that clinicians required considerable amount of time (average 8.4 min) to administer clinician evaluation guide. Due to the above limitation, Spitzer et al., [14] designed a fully self-administered version of original PRIME MD, called PRIME-MD Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ). PRIME-MD PHQ-9 has been found to facilitate the rapid and accurate diagnosis of the depression seen in primary care [15, 16, 17]. Its validity has been established in Indian setting also in which there was a significant positive correlation between diagnosis made by physician and PHQ-9 [18]. The validated Hindi version of PRIME-MD PHQ-9 is also available [19].

In PRIME MD PHQ-9, depression is scored after 9 set of items about symptoms of depression in the past 14 days. Items were scored as 0, 1, 2, and 3 for “not at all”, “several days”, “more than half the days”, and “nearly every day” respectively. Total score was sum of the individual score of the 9 items ranging from 0-27. Patients who had a score more than 4 were diagnosed to be having a depression. Severity of depression was also assessed according to the score as 0-4, 5-9, 10-14, 15-19 and 20-27 were taken as none, mild, moderate, moderately severe and severe respectively [16].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Adult patients i.e., aged equal to or more than 18 years coming out from the OPD consultation rooms were included. Patients who were diagnosed outside the hospital were also included. Seriously ill patients were excluded from the study.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analysed using SPSS software (version 16). Results were presented in simple proportions and percentages. Chi–square test or Fisher’s Exact test (wherever required) was used to observe the differences between proportions. Two way tables were utilized to assess the relationship between dependent (just diagnosed with depression) and independent variables (e.g. education, occupation, marital status). The results were accepted significant if “p” value was less than 0.05. To determine which factors are independently associated with outcome variable, multivariate analysis was also done using binary logistic regression with WHO EPI INFO software.

Ethical issues

All patients were explained the purpose of the study and confidentiality was assured to the patient before taking interview as well as ensured throughout the study. A written informed consent was taken from the participants before start of interview.

Results

Demographic profile of participants

A total of 395 patients were included in the study. Out of 395 participants, 265 (67.1%) were females and 130 (32.9%) were males. Majority were of the age group18-30 years (60%), Hindu (80.8%), married (75.4%) and residing in nuclear family type (60%). 47.3% were illiterate and 65.3% were unemployed. Details of socio demographic profile are shown in [Table/Fig-1].

Demographic characteristics of study subjects

| Characteristic | Male (Percentage) | Female (Percentage) | Total (Percentage) |

|---|

| Age Group(years) |

| 18-30 | 69 (17.5) | 168 (42.5) | 237 (60) |

| 31-40 | 26 (6.6) | 59 (14.9) | 85 (21.5) |

| 41-50 | 14 (3.5) | 24 (6.1) | 38 (9.6) |

| 51-60 | 14 (3.5) | 10 (2.5) | 24 (6.1) |

| More than 60 | 7 (1.8) | 4 (1) | 11 (2.8) |

| Religion |

| Hindu | 104 (26.3) | 215 (54.4) | 319 (80.8) |

| Others(Muslim, Sikh etc) | 26 (6.6) | 50 (12.7) | 76 (19.2) |

| Education |

| Illiterate | 53 (13.4) | 134 (33.9) | 187 (47.3) |

| Primary | 14 (3.5) | 42 (10.6) | 56 (14.2) |

| Middle | 11 (2.8) | 26 (6.6) | 37 (9.4) |

| High school | 11 (2.8) | 9 (2.3) | 20 (5.1) |

| Post High School | 34 (8.6) | 42 (10.6) | 76 (19.2) |

| Graduation and above | 7 (1.8) | 12 (3) | 19 (4.8) |

| Occupation |

| Unemployed | 45 (11.4) | 213 (53.9) | 258 (65.3) |

| Unskilled | 31 (7.8) | 33 (8.4) | 64 (16.2) |

| Semi skilled | 23 (5.8) | 8 (2) | 31 (7.8) |

| Skilled | 9 (2.3) | 2 (0.5) | 11 (2.8) |

| Clerical/ Shop owner/Semi Professional | 9 (2.3) | 5 (1.3) | 14 (3.5) |

| Professional | 13(3.3) | 4(1) | 17 (4.3) |

| Marital status |

| Married | 79 (20) | 219 (55.4) | 298 (75.4) |

| Unmarried | 40 (10.1) | 27 (6.8) | 67 (17) |

| Widow/Separated | 11 (2.8) | 19 (4.8) | 20 (7.6) |

| Type of family |

| Nuclear | 77(19.5) | 160(40.5) | 237(60) |

| Joint/ Three generation | 35(8.9) | 91(23) | 126(31.9) |

| Nuclear extended | 7(1.8) | 14(3.5) | 21(5.3) |

| Staying Alone | 11(2.8) | 0(0) | 11(2.8) |

Prevalence of Depression

Overall prevalence of depression was 30.1% among study subjects. Among 119 patients who were suffering from depression, it was more common among females. 98 (24.8%) females were suffering from depression as compared to 21 (5.3%) males and this difference was significant (χ2= 17.97, p=0.001). Among depressed patients, 47.3% were illiterate. Education status was significantly associated with presence of depression (χ2= 14.3, df=6 and p=0.026). Majority (71.4%) among depressed were unemployed. Depression was also found to be significantly associated with occupation (χ2=13.5, p=0.03). Marital status (widow and separated) was also associated significantly with depression (χ2= 12.46, p=0.006). Out of 25 patients who were known diagnosed cases of depression, only 9 (36%) were taking antidepressant treatment.

Prevalence of unrecognised depression

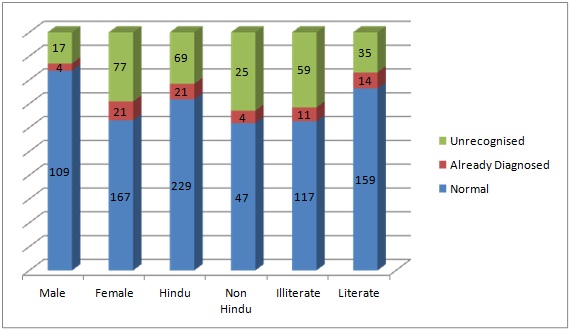

Out of 119 patients who were found to be depressed, 25 (21%) were already diagnosed case of depression and 94 (79%) were detected by using PRIME-MD. So out of the total population studied (395) who had attended OPDs, the prevalence of unrecognised depression was 23.8% (94). To find out specific characteristics of patients who were found to be having unrecognised depression, 25 previously diagnosed patients of depression were excluded from the further analysis. Out of the 94 patients who were diagnosed as depressed, 77 (81.9%) were females and 17 (18.1%) were males. This difference in gender was found to be significantly associated with depression (χ2= 14.30, p=0.001). 62 (66%) belonged to age group 18-30 years but association with age was not found to be significant (χ2= 2.28, p=0.683). 69 (73.4%) of the depressed patients were Hindu. Association with religion was significant with χ2= 4.095, p=0.043. The association with the education status was also seen to be significant (χ2= 11.67, p=0.001) with majority 59 (62.8%) depressed patients being illiterate. Data was also analysed to see association of occupation with depression but it was not found to be associated significantly (χ2= 8.84, df =5, p=0.115). 66 (72.4%) of the patients with depression were married, 13 (13.8%) were widow/separated and 15 (16%) were unmarried. Marital status was also associated significantly with depression (χ2= 7.95, p=0.019). It was found that being widow/separated is significantly associated with depression (χ2= 7.949, df=1, p=0.005) as compared to married/unmarried group. 60 (63.8%) of patients with unrecognized depression were residing in nuclear family type but association with family type was not significant (χ2= 0.976, df=3, p=0.807). Details of distribution among both sexes, occupation and education status are shown in [Table/Fig-2].

Distribution of depression among significant characteristics of study subjects

Data was collected from different OPDs as shown in [Table/Fig-3]. Out of 158 patients in Medicine OPD, 47 (29.6%) were detected as depressed i.e., half of the total unrecognized depression were detected from Medicine OPD. Out of the total Gynaecology patients, 26.2% were detected with depression. Similarly 24.1% of the surgery OPD patients were detected with depression. Unrecognised depression was found relatively less in the Dermatology, ENT and ophthalmology OPD but there was no significant association between OPDs and recognition of undiagnosed depression (χ2= 6.116, df=6, p=0.410).

Distribution of patients of unrecognised depression among different OPDs

| OPD | Number of patients seen*n (%) | Unrecognised depression n=94 (%) | Percentage within the OPD |

|---|

| Medicine | 158 (42.7) | 47 (50) | 29.6 |

| Gynaecology | 42 (11.4) | 11 (11.7) | 26.2 |

| ENT | 37 (10) | 6 (6.4) | 16.2 |

| Ophthalmology | 22 (5.9) | 4 (4.3) | 18.2 |

| Surgery | 29 (7.8) | 7 (7.4) | 24.1 |

| Dermatology | 38 (10.3) | 6 (6.4) | 15.8 |

| Orthopaedics | 44(11.9) | 13 (13.8) | 29.5 |

| Total | 370(100) | 94 (100) | 25.4 |

In 44 (46.8%) patients out of 94 (unrecognized depression), a specific non psychiatric diagnosis could be made by the consulting doctor for their health problems while in 28 (29.8%), the consulting doctor could not make any specific non–psychiatric diagnosis and in rest 22 (23.4%), laboratory investigations were awaited to reach any conclusion about the diagnosis. But this association of presence of unrecognised depression with diagnosis was not found to be significant (χ2= 3.44, p=0.179). Majority i.e. 52 (55.3%) of patients were seen by senior residents, followed by junior residents 24 (25.5%), consultants 10 (10.6%) and internees 8 (8.5%). It was seen that there was no significant association between the category of consulting doctor and unrecognized depression (χ2= 3.22, p=0.35). 23 (24.5%) of the depressed patients were found to be suffering from any other chronic disease while in non–depressed patients, 56 (20.3%) out of 276 were suffering from any other chronic disease, but this difference was not significant (χ2= 0.72, p=0.39). 48 (51.1%) of the depressed patients were seen by the consulting doctor for less than 5 minutes, 40 (42.6%) were seen for 5-10 minutes, 5 (5.3%) were seen for 10-15 minutes and only 1 (1.1%) was seen for more than 15 minutes but there was no significant association between the time spent by the consulting doctor and recognition of unrecognized depression in the outpatient department (χ2= 3.89, p=0.27).

The patients who were found to be depressed were graded according to the severity as shown in the [Table/Fig-4].

Severity grading of patients suffering from unrecognised depression

| Severity grading | Patients with hidden depression n (%) |

|---|

| Mild | 56 (59.6%) |

| Moderate | 28 (29.8%) |

| Moderately severe | 7 (7.4%) |

| Severe | 3 (3.2%) |

To see independent association of gender, religion, educational status and the marital status with the hidden depression, binary logistic regression was applied. It was found that literacy (OR=0.54, CI= 0.328-0.911, p=0.02), and male gender (OR=0.33, CI= 0.183-0.607, p =0.003) were having less Odds of depression whereas widow / separated group had high odds of depression (OR-2.69, CI= 1.162-6.2362, p=0.02) as shown in [Table/Fig-5].

Logistic regression analysis for factors associated with unrecognised depression

| Variable | Adjusted Odd’s ratio | 95% CI | “p” value |

|---|

| Education status (Literate-1) | 0.54 | 0.328-0.911 | 0.020 |

| Marital status (Widow-1) | 2.69 | 1.162-6.2362 | 0.020 |

| Religion (Hindu-1) | 0.64 | 0.3599-1.1663 | 0.147 |

| Gender (Male-1) | 0.33 | 0.183-0.607 | 0.003 |

Discussion

In the present study, 30.1% of the patients were found to be suffering from depression. This finding is similar to the observation made in another study carried out in India by Amin G et al., in which 30% patients crossed the cut-off score for depression [20]. In the present study, depression was found to be more among females, separated/widow and those who were unemployed. Different studies have also shown that depression is more common among female gender [21,22]. Similarly depression was also reported to be prevalent more in widowed or divorced in a study carried out by Poongothai S et al., [6].

Undetected psychiatric morbidity in primary care commonly leads to unnecessary investigation, medication and continued suffering of the patients. This inevitably leads to impaired family, occupational and social functioning [22]. Thus, it becomes crucial for general physicians to be equipped with the necessary skills and measures for detecting and managing these patients. The prevalence of unrecognized depression was 23.1% in the present study. In another study conducted by Spitzer et al., it was found to be 18% [13]. In Indian setting, prevalence of depression in primary care setting ranges from 21-40% [20–25].

Among the socio-demographic characteristics, it was detected more in females as stated in the previous studies also. In study of Ponnudurai R et al., it was shown that depression was more common among younger subjects [26]. However, 66% of the patients belonged to 18-30 years age group but it was not significant in the present study. Some studies have reported high psychiatric morbidity in geriatric as compared to non geriatric population [27], but since in the present study, geriatric constituted only a small percentage (2.8%) of the participants, such association could not be observed. Being Hindu of the participant was significantly associated with depression in present study but another study has shown that it is more common among Muslims [21]. This difference could be due to the presence of higher proportion of Hindus. Unrecognized depression was detected significantly more among illiterates. It shows that literates seek medical care early for depression, perhaps due to greater awareness. Although occupation is not found to be significantly associated with depression in present study but some studies have shown that unemployment is risk factor for depression [20]. In present study, it was detected more in those who are separated or widowed. This goes in line with other studies in which same factor was found to be associated with depression [28, 29]. Family type is not significantly associated with depression but in another study it was found that the nuclear family type was associated with depression [30].

In the present study, 29.6% of patients in Medicine OPD and 26.2% in Gynaecology OPD were detected to be suffering from depression. In the studies conducted by Krishnamurthy et al., in general (Medicine) OPD population and Agarwal et al., in Gynaecology OPD, the percentage of patients having psychiatric morbidities was 36% and 49.9% respectively [28, 31]. As we have focused only on depression, the other psychiatric morbidity could also have increased the prevalence in OPD attendees. No association was found between specific medical diagnosis and detecting depression in patients which shows that depression can be present in any patient irrespective of the medical diagnosis. 24.5% of the patients with unrecognized depression were suffering from any chronic disease but this association was not significant. Similar finding were shown by Steven D et al., which stated that depression screening results were not found to be associated with the likelihood of having any well-defined chronic medical condition [12]. This shows that depression can be presented in any patient whether or not patient has chronic illness.

Conclusion

Unrecognized depression is common in non-psychiatric OPDs. There is a need to screen patients presenting in such OPDs for depression. Primary health care research and health personnel need to recognise this as an important entity and focus on detection of unrecognised form of depression which may be perhaps due to lack of awareness among patients and providers. Predictors of depression among OPD attendees are female gender, illiteracy, widow or separated. This requires an effective mental health care policy and implementation of mental health program in the rural primary healthcare institutions of the country.