Aim: To assess the risk factors, the mortality and the “near-miss” morbidity in primary PPH.

Setting and Design: A retrospective analysis of 124 women with PPH (within 24 hrs of delivery) over 4 consecutive years in a tertiary care hospital in rural bangalore.

Material and Methods: The case sheets of the patients, which were identified by the labour record registers as having PPH were reviewed by the same person, to identify the actual impact of the condition. The data was analyzed by Chi-square analysis.

Result: PPH (the loss of blood that caused significant alterations in the maternal condition or a blood loss of 500 cc in vaginal deliveries or of >1000 cc in caesarean sections) was recorded in 124 women; 60 had delivered in hospitals (Group-A) and 64 had been referred after their deliveries (Group-B) from various peripheral centres, i.e., maternity hospitals, nursing homes and district and community health centres. The maternal mortality ratio during this period was 71/100,000 (4 deaths/5600 live births). Of these 4 deaths, 0 were in group A and 4 were in group B. The “near-miss” morbidity was higher than the mortality (total 20/124; 6/60 in Group-A and 14/64 in Group-B). The delayed referrals and the lack of an active 3rd stage management in Group-B were responsible for most of the adverse events.

Conclusion: Both the “near-miss” morbidity and the mortality in PPH reflect the level of obstetric care in the developing world. These need to be reduced by strengthening the peripheral delivery facilities, the active 3rd stage management and the timely referrals.

INTRODUCTION

Primary postpartum haemorrhage is a leading cause of maternal mortality and morbidity internationally. In Africa and Asia, haemorrhage (all types) accounts for approximately one-third of all the maternal deaths [1] Primary postpartum haemorrhage is often defined as a blood loss of over 500 mL during or within the first 24 hours after the delivery [2]. Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) has been a nightmare for obstetricians since centuries [3–4] in the third stage management by birth setting, significantly fewer women who gave birth at home had a blood loss of between 501 and 1,000 mL or greater than 1,000 mL than the women who gave birth at a tertiary hospital.

Two broad approaches to the management of the third stage of labour are used: active (by using a uterotonic drug) or physiological (also known as “expectant” and omitting the use of a uterotonic drug). These approaches have been described in a consensus statement by the New Zealand College of Midwives [5]. A retrospective cohort study (n = 33,752) which was done in New Zealand (by using the same database which was accessed for this study) [6], which focused on the third stage management of low-risk women, found that 48.1 percent of this group experienced a physiological third stage of labour. Higher proportions of women who gave birth at home and in primary settings had a physiological third stage of labour as compared to those who gave birth in secondary and tertiary hospitals. Despite this important difference in the third stage management by birth setting, significantly fewer women who gave birth at home had a blood loss of between 501 and 1,000 mL or greater than 1,000 mL than the women who gave birth at a tertiary hospital.

Currently, in the developed countries, embolism is the leading cause of the maternal mortality [7] However, in the developing countries, PPH continues to be a leading cause, accounting for 25-43% of the maternal deaths [8,9]. A primary observational study reported that a blood loss of more than 500 ml occurs in 40% women after vaginal deliveries and of more than 1000 ml in 30% women after elective repeat caesarean sections [10]. The WHO technical working group 1990, defined PPH as a bleeding in excess of 500 ml in the first 24 hrs after the delivery [11]. PPH is a frequent complication of deliveries and its incidence is commonly reported as 2-4% after vaginal deliveries and 6% after caesarean sections, with uterine atony being the cause in about 50% of the cases [12].

Every minute, at least one woman dies from the complications which are related to pregnancy or childbirth – that means 529 000 women a year. The WHO PROJECT REPORT MAY 6, 2011. In addition, for every woman who dies in childbirth, around 20 more suffer injury, infection or disease – approximately 10 million women each year. Five direct complications account for more than 70% of the maternal deaths: haemorrhage (25%), infection (15%), an unsafe abortion (13%), eclampsia (very high blood pressure which leads to seizures – 12%), and obstructed labour (8%). While these are the main causes of the maternal death , an unavailable, inaccessible, unaffordable, or a poor quality care is also fundamentally responsible. They are detrimental to the social development and the wellbeing, as some one million children are left motherless each year. These children are 10 times more likely to die within two years of their mothers’ deaths.

Many studies have suggested this to be an underestimation of the normal loss and some have suggested that the cutoff for the clinically significant PPH should now be revised to 1000 ml [13]. The aim of this study was to identify the causes of PPH and to assess the extent of the morbidity, especially for the “near-miss” cases as well as the mortality which was associated with them. The “near-miss” morbidity is considered to be an underestimated but a more sensitive indicator of the maternal health than the mortality. Worldwide, postpartum haemorrhage is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality, with the highest incidence in the developing countries (the average is 18 times higher than that in the develuped countries at 480 deaths per 100,000). According to the World Health Organization, an bstetric haemorrhage causes 127,000 deaths annually world wide [14]. The increased prevalence of the risk factors such as a grand-multiparty, coupled with poorly developed obstetric services, makes an obstetric haemorrhage responsible for 30% of the total maternal deaths [15].

Our study attempted to know the impact of a primary post partum haemorrhage at a tertiary care centre where the cases were referred from primary health centres, community health care centres and local nursing homes, in addition to the women who delivered at our centre. Most of the referred cases had a disturbed management of the third stage of labour, which could lead to a severe form of morbidity and mortality.

AIM

To assess the risk factors, the mortality and the “near-miss” morbidity in PPH in rural Bangalore, India.

SETTING AND DESIGN

A retrospective analysis of 124 women with PPH (within 24 hrs of their deliveries) over 4 consecutive years at a tertiary care hospital in rural Bangalore, India.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This study was carried out in MVJ Medical College and Research Hospital which is a tertiary care hospital in rural Bangalore, India. After obtaining the institutional ethical committee’s clearance, written informed consents were taken from all the women/ family members in case of MMR. A retrospective analysis of all the women with PPH (within the first 24 hrs of their deliveries) during a period of 4 consecutive years (2008 to 2012), was done by the same person. The PPH in the institute was measured both objectively and subjectively, i.e., any amount of blood loss following birth, that adversely affected the mother as well as a loss of > 500 ml in vaginal deliveries and of > 1000 ml during caesarean sections (which were estimated from the use of sponges and the blood in suction by the attending staff). Mild PPH blood loss is 500ml to 700ml, moderate PPH blood loss is 700ml to 1000ml and severe PPH blood loss is more than 1000ml. The criteria for the diagnosis of the deliveries which had taken place outside the institute was not clear, but since they were referred with a diagnosis of PPH from outside and as most of them were in a moribund state, no exact definition was sought from them. Such women were identified from the labour record registers and then all the case sheets were reviewed and the demographic variables of age, parity, the period of gestation and the mode of the delivery were noted. The cause of the PPH and the medical or surgical interventions were analyzed. A morbidity assessment was done and the “near-miss” morbidity was identified by using the scoring system which was outlined by Geller et al. [16,17].

A “near-miss” morbidity is considered as a sensitive indicator of the assessment [18]. In this system, five clinical factors - organ failure (3 1 system), extended intubation (312 h), ICU admission, surgical intervention and transfusion (33 units) are – grouped into a scoring system. The total score is calculated as the weighted sum of the clinical factors which are present for each woman. This scoring system has a specificity of 93.9%. The total score was calculated as the weighted sum of the clinical factors which were present for each woman, with a score of 38 being considered as a “near-miss” morbidity. In our hospital, the active management of the 3rd stage, in the form of intramuscular ergometrine at delivery, of the anterior shoulder or 10-20 units of oxytocin infusion in 500 ml of normal saline and a controlled cord traction are practised routinely. A note was made of similar practices which were carried out outside.

RESULTS

During the study period, a total of 5600 women delivered in our hospital. Of these, 60 had PPH (with an incidence of 1.07%). In addition, 64 women were referred from peripheral health centres with PPH. Thus, we had a total of 124 women with PPH for analysis. The mean age of the women was 26 years and the mean gestational age at delivery was 37.6 weeks. About half of the women (48%) were primiparous and the pregnancies had been supervised only in about one-fourth of the women (26.4%). The onset of labour was spontaneous in 50.6% women and 65.7% had delivered vaginally. For the purpose of the analysis, we divided the women with PPH into two groups - Group A (the women who delivered in this hospital, n=60) and Group B (the women who were referred after having delivered elsewhere n=64).

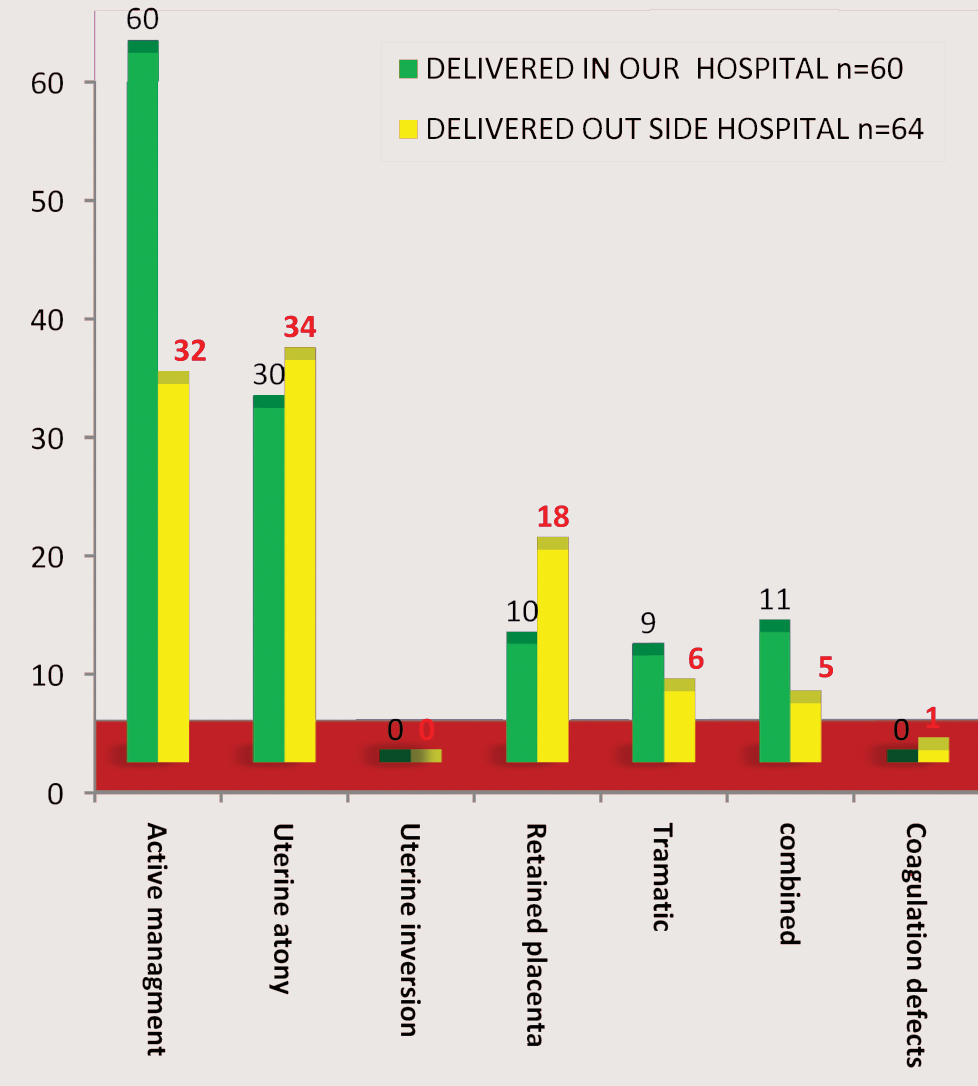

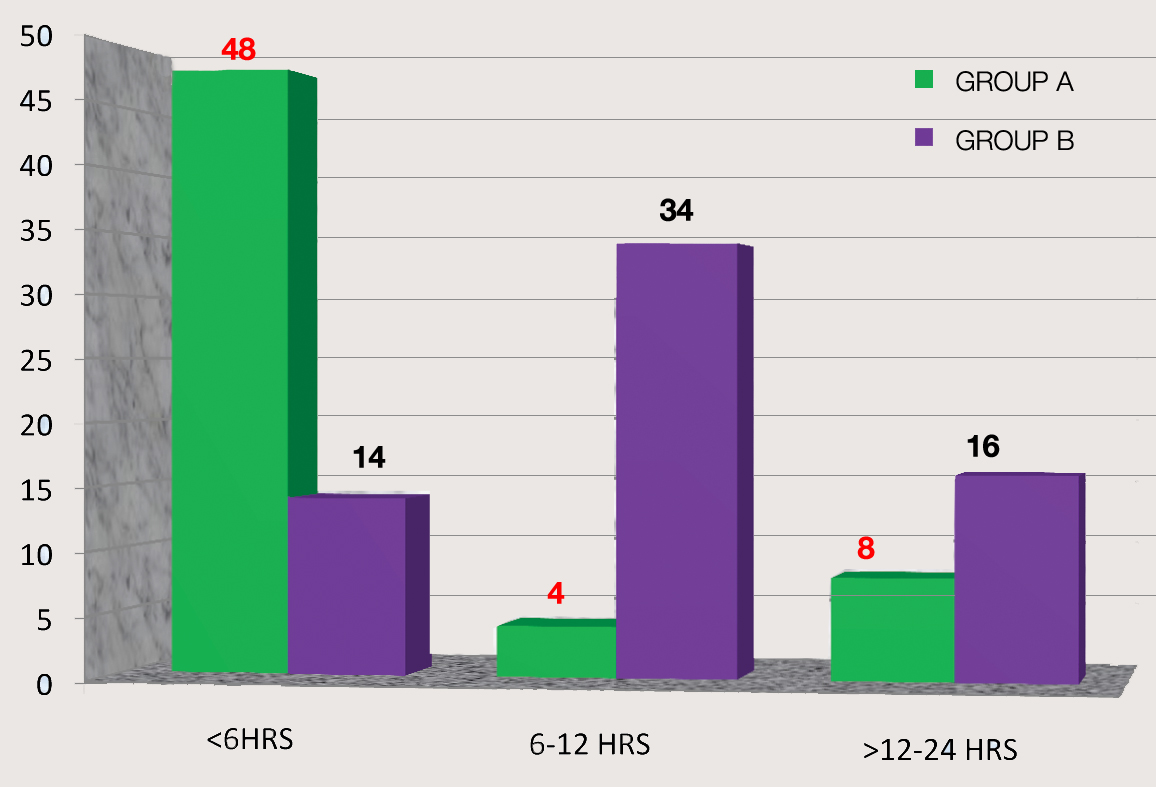

[Table/Fig-1] shows the labour characteristics and the causes of PPH in the two groups. In our hospital, the active management of the 3rd stage is practised routinely. However, the routine active management of the 3rd stage, though it was recommended by the WHO, was practised in only 50% of the women in Group B. This fact may be responsible for the finding that though uterine atony had emerged as the leading cause of PPH in both the groups, it was significantly higher (almost double) in those who had delivered elsewhere and had been referred to this hospital with PPH. The atonicity in group B was also contributed to by the retained placental tissue and the uterine inversion, thus highlighting the need for proper delivery techniques. In a majority of the women (80%), excessive bleeding had occurred within 6 hours of their deliveries. However, a majority (53.4%) of the women who had delivered elsewhere had reached our hospital after 6 hours, thus losing precious time.

Shows the labor characteristics and causes of PPH in the two groups

| Group A n=60 | Group B n=64 | P value |

|---|

| Active management | 60 (100) | 32 (50%) | <0.05 |

| Timing of presentation |

| <6HRS | 48 (80%) | | |

| 6-12 HRS | 4 (6.6%) | | |

| >12-24 | 8 (13.3%) | | |

| Timing of referral |

| <6HRS | | 14 (21.8%) | |

| 6-12 HRS | | 34(53.1%) | |

| >12-24 | | 16 (25%) | |

| Uterine atony | 30(50%) | 34 ( 53.1%) | <0.05 |

| Uterine inversion | 0 | 0 | |

| Retained placenta | 10 (16.6%) | 18 (28%) | |

| Tramatic | 9 (15%) | 6 (9.3%) | |

| Perinanal injuries | 4 (6.6%) | 1 (1.5%) | |

| Cervical lacerations | 5 (8.3%) | 1(1.5%) | |

| Uterine rupture | 0 | 4(6.25%) | |

| Combined | 11 (18%) | 5 (7.8%) | |

| Coagulation defects | 0 | 1(1.5%) | |

The frequency and the severity of the complications were more in group B. Amongst the injuries, lower genital tract trauma was significantly more in the hospital deliveries, but uterine rupture was more in the referred group (although it was not statistically significant).

[Table/Fig-2] shows the overall morbidity and the mortality data. There was a total of 4 deaths among the 124 women with PPH (with a mortality rate of 3.2%). During the study period, there were 5600 live births at our hospital . The maternal mortality ratio during this period was 71/100,000 (4 maternal deaths/5600 live births). Between the two groups, all the deaths were among the women who had delivered elsewhere and had been referred with PPH,. Thus, though the overall mortality was not significantly different, a majority of the deaths in Group B were associated with multiple organ failure, which is an indirect indicator of the delay in the initiation of the treatment.

Mortality and Morbidity due to Primary PPH

| Group a(n=60) | Group b(n=64) |

|---|

| Mortality | 0 | 4(2.5%) |

| Rupture uterus | 0 | 2 (50%) |

| Coagulopathy | 0 | |

| Uterine inversion | 0 | |

| Organ system failure | 0 | 2(50%) |

| Near miss morbidity | 8(13%) | 24(37%) |

| Organ failure | 0 | 2 (0.08%) |

| Icu admission | 8(13%) | 18 (28.12%) |

| Extended intubation | 1 (1.6%) | 2 (3.12%) |

| Transfusion >3 u | 5(8.3%) | 22(34.37%) |

| Surgical intervention | 2(3.3%) | 12(18.75%) |

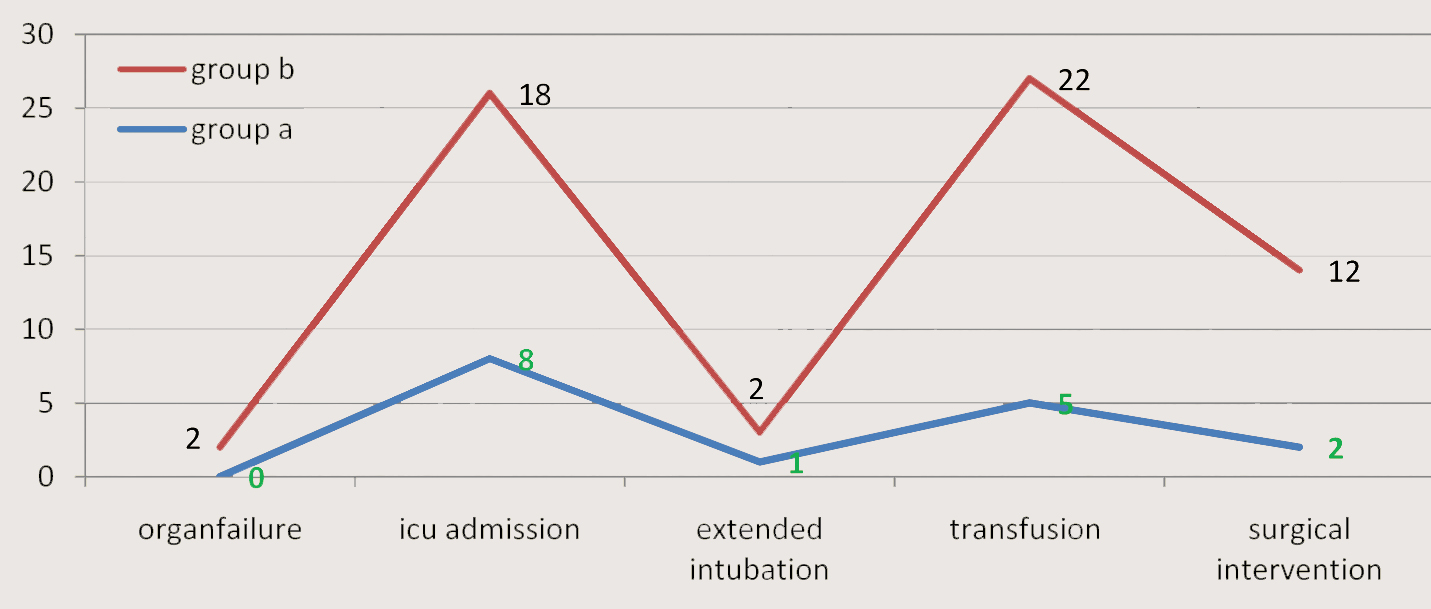

An attempt to analyze the “near-miss” morbidity (the cases that could easily have progressed to mortality) was made, in order to identify the factors that could trigger events that could ultimately lead to maternal mortality. 32 women (25.8%) suffered a “near-miss” morbidity. The causes for the “near-miss” morbidity in the women who delivered in our hospital (Group A) were uterine atony (4 cases), followed by retained placentae (3 cases) and cervical lacerations (1 case). Amongst the referred cases (Group B), uterine atony, retained placentae and ruptured uteri accounted for 7, 13 and 4 cases respectively. Amongst the 32 women, the major group comprised of referral patients. A delayed referral (a transfer time of > 6 hours after the delivery) was observed in Group B in 50/64 (78 %) women and all the 32 women who had the “near-miss” morbidity had reached our hospital at > 6 hours after their deliveries.

Although a score of 38 was taken as the cutoff for the near-miss morbidity evaluation, as shown in [Table/Fig-2], the individual factors which were assessed were high and their impact on the quality of life could not be understated. Again, a comparison between the two groups revealed a higher rate of complications in the referred group with organ failure, which was sevenfold more, while the ICU admission, the extended intubations and the 3 units transfusion rate were fourfold more and the surgical interventions were six-fold higher than in those who had delivered in our hospital.

In [Table/Fig-3], the details of the morbidity in all the cases revealed a significantly high morbidity in all these women and again, a greater number amongst the outside deliveries, with cardiac causes (hypotension) mainly contributing to the organ system failure. The major surgical interventions which included hysterectomy and bilateral uterine artery ligation were required in more cases in Group B, thus signifying the severity of the complications in this group.

| Group A n=60 | Group B n=64 |

|---|

| Organ system failure |

| Cardiac arrest,hypotension | 10 (16.6%) | 40 (62.5%) |

| Pulmonary (arrest, intubation, ards) | 2 (3.3%) | 4 (6.25%) |

| Coagulation defects | 0 | 2 ( 3.12%) |

| Coma | 0 | 0 |

| Renal failure | 0 | 2 (3.12%) |

| Surgical intervention | 2(3.3%) | 12 (18.75%) |

| Hysterectomy | 2(3.3%) | 7 (10.9%) |

| Uterine artery ligation | 0 | 5 (7.81%) |

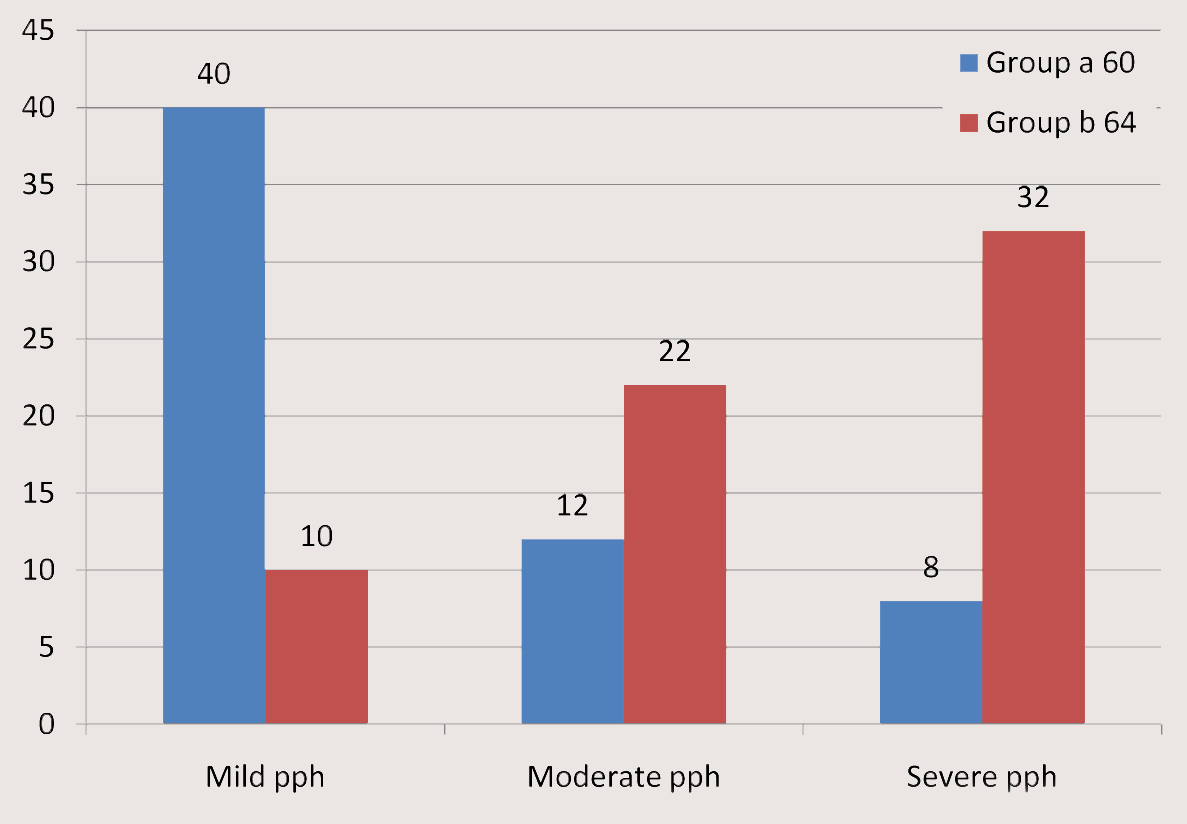

Morbidities in mild, moderate, severe pph cases in Group A

| N= 60 | Organ Failure | ICU Admission | Transfusion | Extended Intubation | Surgical Intervention |

|---|

| Mild pph | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | | |

| Moderate PPH | 12 | 0 | 2 | 1 | | |

| Severe PPH | 8 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

Morbidities in mild, moderate, severe pph cases in Group B

| N= 64 | Organ Failure | ICU Admission | Transfusion | Extended Intubation | Surgical Intervention |

|---|

| Mild PPH | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | | |

| Moderate PPH | 22 | 0 | 6 | 5 | | 3 |

| Severe PPH | 32 | 2 | 12 | 16 | 2 | 9 |

Incidence of mild, moderate and severe pph cases in Group A and Group B

Morbidity trends in Group A vs Group B: Group B having higher morbidity than Group A

Frequency of mild, moderate, severe post partum hemorrhage in group a, and group B.

DISCUSSION

The exact incidence of PPH is difficult to determine, due to the difficulty in accurately measuring the blood loses. Most of the studies have quoted figures which ranged from 5 to 12% for vaginal deliveries [19, 20].

The maternal mortality has been used traditionally as a measure of the quality of the health care. However, recently, the maternal morbidity, especially, the “near miss” morbidity, is being taken into account to assess the burden of the disease. Apparently, two-thirds of the obstetric morbidity is related to haemorrhage [17]. It has been estimated that PPH increases the risk of the morbidity 50 times and that it has 5 times higher morbidity than the mortality [20]. This study attempted to analyze the data of the women who had PPH over a 4-year period – in order to identify the causes, the mortality and the “near-miss” morbidity which were associated with it as well as the risk factors that contributed to the adverse outcomes.

An assessment of the causes of PPH revealed that the incidences of uterine atony, retained placentae and uterine inversions were significantly less among the women who had delivered at our hospital as compared to the women who had been referred with PPH after having delivered elsewhere. The regular use of an active management in the 3rd stage, as well as a prompt recognition of the complications, with the institution of the appropriate management, emerges as the obvious reason. The main causes of PPH among the hospital delivery group (Group A) were atony and retained placentae; which are not always associated with the significant morbidity for the surgical intervention [21]. The time of presentation of the PPH in Group A in a majority (87%) of the cases was within 6 hours of the delivery, which highlighted the need for a continuous vigilance postpartum and a prompt action in case of problems [6, 7].

The mortality in Group B was more than that in Group A, despite the fact that our hospital catered to a high-risk population (4 versus 0). This implies that PPH persists as a cause of mortality despite providing adequate intranatal care [21–23]. The evaluation of the causes of mortality showed that multiple organ failure was the major cause of the mortality in the referred cases and in all these cases, the underlying event was uterine atony, which emphasized the need for an active management of the labour and a prompt management of the PPH if it occurred. Such a prevention could be meaningfully achieved by the use of an active management of the 3rd stage of labour (oxytocics at the anterior shoulder, controlled cord traction and primary cord-clamping), which causes a reduction in the blood loss, postpartum anaemia, a need for transfusion and the severity of the PPH if it occurs [24][Table/Fig-4,5,6 and 7].

This study also highlighted that the mere assessment of the mortality data was not enough. The morbidity parameters are more sensitive and efficient. The incidence of morbidity was quite high in our study. A total “near-miss” morbidity incidence of 39.6% was observed in our study, which was much higher than the reported incidence of 0.05-1.2% [19,25,26]. Also, the comparison revealed that the referred cases had significantly more morbidity [Table/Fig-8 and 9]. Organ failures, ICU admissions, intubations, blood transfusions and surgical interventions were significantly higher among the referred group. The organ failures and surgical interventions had increased fourfold and six-fold respectively; while ICU admissions, extended intubations and transfusions of >3 units were two fold higher among the referred cases. This revealed that the morbidity parameters were much more sensitive and that they should be incorporated in the clinical reviews to evaluate the actual burden of the problem and to find better and effective management strategies. Overall, the hospital deliveries had better outcomes, milder courses and less severities, thus again implicating a substandard care/delayed care as significant, as was shown by other studies [27]. The significantly less morbidity and the “near-miss” cases among the hospital deliveries reflected that the prompt institution of the active 3rd stage management in all the cases had helped in reducing the complications. However, since the sample size was small, it is difficult to compare both the mortality and the morbidity amongst the hospital and the non-hospital deliveries. Fahy [27] reported that 2.6 percent of the women in their cohort study had a blood loss which was greater than 1,000 mL, and Rogers et al., [28] identified in their randomized controlled trial that 2 percent (90/3,436) of the women had a blood loss which was greater than 1,000 mL.The report of Thompson et al., [29] demonstrated that 2.3 percent of the women who gave birth vaginally had a blood loss of 1,000 mL or more but which was less than 1,500 mL and that 1.6 percent had a blood loss of 1,500 mL or more. In the present study, 40.3% of the women had a blood loss which was between 500-700 ml, 27.4% had a blood loss which was between 700-1000 ml and 32.2% had a blood loss of more than 1000ml.

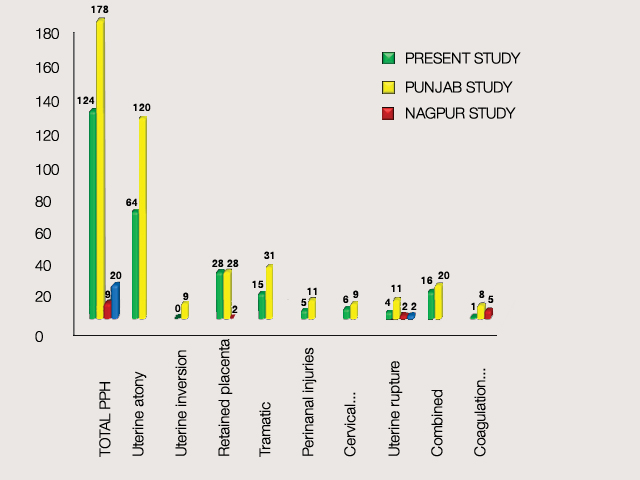

Comparision of Causes of Post Partum Hemorrhage in Various Studies in India

Comparision of Causes of Postpartum Hemorrhage I Patients Delivered at our Hospitals and Those Delivered Out Side Our Hospitals Table 1

A more recent Swedish trial [4] which was done on low-risk women (although it also potentially included women who had experienced an induction or an augmentation of labour), which compared the physiological third stage with the active management, reported a high rate of severe postpartum haemorrhages—13.5 percent overall. The physiological group was significantly more likely to experience a blood loss of greater than 1,000 mL, but it was no more likely to have a blood transfusion than that of the active management group [Table/Fig-10].

Bar Chart Showing the Number of Patients Who are in Asses to Emoc at 6,6-12,12-24 Hrs

The “near-miss” morbidity score was started with the intention of evaluating the existing problem in the developed world, where the maternal mortality is on the decline; yet the same can be used to identify the load of the significant maternal morbidity in the developing countries, since it is a sensitive indicator of the pregnancy outcome [13,19–21, 24]. Most of the studies have implicated that haemorrhage contributes to 24-64.8% cases of “near-miss” obstetric morbidity and our study also showed that the “near-miss” morbidity assessment was significantly more informative than the mortality [30–34]. Therefore, its evaluation, along with the prediction of the risk factors, will reduce the disease burden and improve the health status. Similar conclusions have also been reached in other studies [19]. In conclusion, an assessment of the “near-miss” morbidity is as important as the mortality data, for evaluating the actual brunt of the disease in the developing world, where a significant morbidity assumes demonic proportions by affecting the quality of life and giving a tsunamic blow to the already staggering economy [35–37].

CONCLUSION

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) is an obstetrical emergency which follows a delivery. It is a major cause of maternal morbidity, and one of the top three causes of maternal mortality. Haemorrhage is the leading cause of the admissions to the intensive care unit and the most preventable cause of the maternal mortality. An efficient management of the third stage of labour can significantly reduce the need for surgical interventions in managing the post partum haemorrhage. The near miss cases can be significantly reduced by the hospitals which adopt the policies of an active management of the third stage of labour and timely referrals.

[1]. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: A systematic reviewLancet 2006 367:1066-74. [Google Scholar]

[2]. The World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines for the Management of Postpartum Haemorrhage and Retained Placenta. Geneva: Author, 2009 [Google Scholar]

[3]. Hastie C, Fahy K, Optimising psychophysiology in third stage of labour: Theory applied to practiceWomen Birth 2009 22:89-96. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Jangsten E, Mattsson LA, Lyckestam I, A comparison of active management and expectant management of the third stage of labour: A Swedish randomised controlled trialBr J Obstet Gynaecol 2011 118(3):362-36. [Google Scholar]

[5]. New Zealand College of Midwives. The Third Stage of Labour. NZCOM Practice Guidelines. Christchurch: Author, 2006 [Google Scholar]

[6]. Dixon L, Fletcher L, Tracy S, Midwives care during the third stage of labour. An analysis of the New Zealand College of Midwives Midwifery Database 2004–2008NZ College Midwives 2009 41:20-25. [Google Scholar]

[7]. The Department of Health. Why mothers die. Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom 1994-1996. Department of Health (UK): London; 1998 [Google Scholar]

[8]. Tuncer RA, Erkaya S, Siphai T, Kutlar I, Maternal mortality in a maternal hospital in TurkeyActa Obstet Gynecol Scand 1995 74:604-06. [Google Scholar]

[9]. al-Meshari A, Chattopadhyay SK, Younes B, Hassonah M, Trends in maternal mortality in Saudi ArabiaInt J Gynecol Obstet 1996 52:25-32. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Pritchard JA, Baldwin RM, Dickey JC, Wiggins KM, Blood volume changes in pregnancy and the puerperium II. Red blood cell loss and changes in apparent blood volume during and following vaginal delivery, cesarean section and cesarean section plus total hysterectomyAm J Obstet Gynecol 1962 84:1271-82. [Google Scholar]

[11]. The World Health Organization. The prevention and management of post partum haemorrhage. Report of a technical working group. WHO: Geneva; 1990 [Google Scholar]

[12]. Amy JJ, Severe postpartum haemorrhage: A rational approachNatl Med J India 1998 11:86-8. [Google Scholar]

[13]. Drife J, Management of primary post partum haemorrhageBr J Obstet Gynaecol 1997 104:275-7. [Google Scholar]

[14]. World Health Organization, authorReducing the global burden: Postpartum Haemorrhage 2008 [5 December 2008] [Google Scholar]

[15]. Khan KSW, WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: a systematic reviewLancet 2006 367:1066-74. [Google Scholar]

[16]. Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox SM, Kilpatrick S, Defining a conceptual framework for near-miss maternal morbidityJ Am Med Women Assoc 2002 57:135-9. [Google Scholar]

[17]. Geller SE, Rosenberg D, Cox S, Brown M, Simonson L, Kilpatrick S, A scoring system identified near miss maternal morbidity during pregnancyJ Clin Epidemiol 2004 57:716-20. [Google Scholar]

[18]. Drife JO, Maternal ¢Near-miss¢ reports?BMJ 1993 307:1087-8. [Google Scholar]

[19]. Waterstone M, Bewley S, Wolfe C, Incidence and predictors of severe obstetric morbidity: Case-control studyBMJ 2001 322:1089-94. [Google Scholar]

[20]. Anonymous Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom 1991-1993. HMSO: London; 1996 [Google Scholar]

[20]. Grimes DA, The morbidity and mortality of pregnancy: Still risky businessAm J Obstet Gynecol 1994 170:1489-94. [Google Scholar]

[21]. Berg CJ, Atarsh HK, Koonin LM, Tucker M, Pregnancy related mortality in the United States, 1987-1990Obstet Gynecol 1996 88:161-7. [Google Scholar]

[22]. Kwask BE, Post- partum hemorrhage: Its contribution to maternal mortalityMidwifery 1991 7:64-70. [Google Scholar]

[23]. Prendiville WJ, Elbourne D, McDonald S, Active versus expectant management in the third stage of labor (Cochrane review)Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000 3:CD000007 [Google Scholar]

[24]. Fitzpatrick C, Halligan A, McKenna P, Coughlan BM, Darling MR, Phelan D, Near miss maternal mortality (NMM)Ir Med J. 1992 85:37 [Google Scholar]

[25]. Mantel GD, Buchmann E, Rees H, Pattinson RC, Severe acute maternal morbidity: A pilot study of a definition for a near-missBr J Obstet Gynaecol 1998 105:985-90. [Google Scholar]

[26]. Combs CA, Murphy EL, Laros RK Jr, Factors associated with post partum hemorrhage with vaginal birthObstet Gynecol 1991 77:69-76. [Google Scholar]

[27]. Fahy K, Third stage of labor care for women at low risk of postpartum hemorrhageJ Midwifery Womens Health 2009 54(5):380-86. [Google Scholar]

[28]. Rogers J, Wood J, McCandlish R, Active versusexpectant management of the third stage of labour: The Hinchingbrooke randomised controlled trialLancet 1998 351(9104):693-99. [Google Scholar]

[29]. Thompson J, Baghurst P, Ellwood D, Benchmarking Maternity Care 2008–2009 2010 Canberra, AustraliaWomen’s Hospitals Australasia [Google Scholar]

[30]. Stones W, Lim W, Al-Azzawi F, Kelly M, An investigation of maternal morbidity with identification of life-threatening ‘Near miss’ episodesHealth Trends 1991 23:13-5. [Google Scholar]

[31]. Bewley S, Creighton SB, ‘Near-miss’ obstetric enquiryJ Obstet Gynaecol 1997 17:26-9. [Google Scholar]

[32]. Baskett TF, Sternadel J, Maternal Intensive Care and near miss mortality in ObstetricsBr J Obstet Gynecol 1998 105:981-4. [Google Scholar]

[33]. Brace V, Penney G, Hall M, Quantifying severe maternal morbidity: A Scottish population studyBr J Obstet Gynecol 2004 111:481-4. [Google Scholar]

[34]. Rowan K, Golfrad C. Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre ICNARC. July 2000 [Google Scholar]

[35]. Murphy DJ, Charlett P, Cohort study of near-miss maternal mortality and subsequent reproductive outcomeEur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2002 102:173-8. [Google Scholar]

[36]. Tang LC, Kwok AC, Wong AY, Lee YY, Sun KO, So AP, Critical care in obstetrical patients: An 8 year reviewChin Med J Eng 1997 110:936-41. [Google Scholar]

[37]. Kaul V, Bagga R, Jain V, Gopalan S, The impact of primary postpartum hemorrhage in “near-miss” morbidity and mortality in a tertiary care hospital in north IndiaIndian J Med Sci 2006 Jun 60(6):233-40. [Google Scholar]