A prescription order is an important document between the physician and the patient. Prescription writing is an important aspect, which needs to be continuously assessed and refined suitably and it reflects the physician’s skill in the diagnosis and attitude towards selecting the most appropriate cost effective treatment [1,2].

The quality of life can be improved by enhancing the standards of the medical treatment at all levels of the health care delivery system. A medical audit oversees the observance of these standards [3]. An ‘audit’ is defined as ‘the review and the evaluation of the health care procedures and documentation for the purpose of comparing the quality of care which is provided, with the accepted standards’ [4]. Studying the prescribing pattern is that part of the medical audit which seeks to monitor, evaluate and if necessary, suggest modifications in the prescribing practices of medical practitioners, so as to make the medical care rational and cost effective [5].

There is ample international evidence that poor quality prescription writing increases the risk of serious medication errors [6]. Research has confirmed that didactic sessions and a passive Pharmacology Sectiondissemination of guidelines are not effective means of modifying the prescriber’s behaviour. Conversely, a combination of prescription audits and feedback is known to be a successful technique which improves the quality of the prescribing [7].

Typically, when the feedback is combined with the audit as a strategy to improve the prescription writing quality, it should be of a generalized nature rather than an individualized nature. However, the audits which involve an individualized feedback have been shown to be effective in improving the compliance with the guidelines for the treatment of medical conditions. Very few studies have revealed the impact of serial prescription audits and feedback on the quality of the prescription writing [8]. In addition to this, our study also focused on how long the effect of an audit and feedback lasted in the prescription behaviour, a fact which we have not come across in any study.

The main objective of this study was to study the impact of serial audits with active feedback on the prescription behaviours of the prescribers in terms of the quality of the prescription writing. Another focus was to see the level of the impact after a duration gap which was introduced between the two audits.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Institutional Ethical Committee (IEC) approval was received before the initiation of this study. This study was conducted in compliance with Schedule -Y and the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) regulatory guidelines of India. Serial prescription audits in four cycles were conducted at Jhalawar Medical College, Rajasthan and at Chintpurni Medical College, Punjab for one year (for a total of 2 years) in each of these two hospitals. One cycle included the prescriptions which were collected with a digital camera from the outdoor patients department every month, for three months regularly (n=250 per month, total 750 in each cycle). A baseline prescription audit was done on the last date of the first month and the prescribers were provided with the feedback. Re-audits were done on the last date of the 2nd and 3rd months, which concluded one cycle. One cycle was followed by three months of no prescription audit. The next three cycles were repeated in the same way and a total of four cycles were completed in two years. A continuous evaluation and a feedback process were done every month. The data was analyzed by using the Chi-square test.

The data which was observed monthly was analyzed, based on the following parameters-(a) details of the formats of the prescriptions (b) the WHO drug core indicators and (c) legibility of the prescriptions. Every audit was done as a cross-sectional survey over a month. The contents of the prescriptions were assessed and an evaluation was done on the basis of the extent of conformity to the WHO guide to good prescribing, the updated WHO list of Essential Medicines and the WHO Policy Perspectives on Medicines [9–12].

The details of each prescription were analyzed on the basis of the following parameters.

1. For the Prescription Format:

(a) The patient’s identity: Name, age and address.

(b) Date: Day on which the prescription was written.

(c) Superscription: The symbol, Rx signifies recipe or “take thou”.

(d) Inscription: Medication information and drug-generic or brand name.

(e) Subscription: Dispensing direction for the pharmacist.

(f) Transcription: Direction to the patient as to how to take the drugs.

(g) Signature: Prescriber identity, name, address and qualification.

2. The Core Drug Use Indicators

The WHO core drug use indicators for out-patient facilities were used to study the prescribing practices. The core drug use indicators which were included were:

The average number of drugs per encounter.

The percentage of the drugs which were prescribed by generic names.

The percentage of the encounters with an antibiotic which was prescribed.

The percentage of encounters with an injection which was prescribed.

The percentage of drugs which were prescribed from the essential drugs list or formulary.

3. Clarity of the prescriptions: Clarity means the legibility of writing as well as the use of approved abbreviations, to avoid any omission which would influence the ability to discern the correct meaning of the prescribed drugs. The legible prescriptions should be readable without difficulty by someone who is not familiar with the context. Another method for grading the prescriptions, based on their clarity, is to assess the difficulties in reading the prescriptions, which are faced by the pharmacists who dispense them.

The initial assessment of the clarity was undertaken by picking up the prescriptions which were difficult to read or were unclear i.e. prescriptions which could potentially be assigned a score of ‘1’ or ‘2’. These prescriptions were then reassessed by a consensus group, which also included a pharmacist and a physician. In case of a discrepancy between the scores which were assigned by the consensus group, a second consultant physician was consulted [Table/Fig-1].

Scoring tool for legibility of prescriptions

| Score | Standard | Meaning |

|---|

| 0 | Clear | Standard of clarity is such that the prescription can easily be read and interpreted, and acted on with confidence |

| 1 | Some difficulty with clarity | Standard of clarity is such that there is difficulty in reading and/or interpreting one or more parts of the prescription and there is a possibility of misinterpretation. |

| 2 | Unclear | Standard of clarity is such that the one or more parts of instructions/meaning cannot be fully discerned and the prescription cannot be acted on with confidence. |

RESULTS

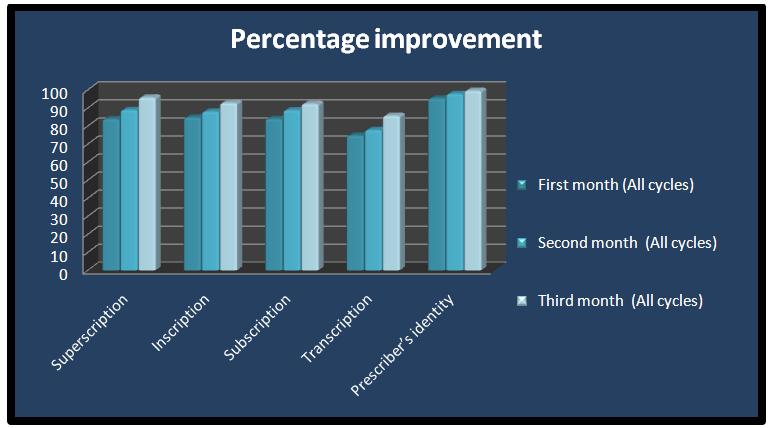

During the study period, a total of 3000 prescriptions were collected in 4 cycles and each cycle included 3 months and 750 prescriptions (n=250 per month). The results of the base line data for the first month of every cycle were compared with those of the 2nd and 3rd re-audits. The total baseline data of the first months of all the cycles were also compared with those of the 2nd and 3rd re-audits of all the cycles. All the prescriptions had clearly documented the patients’ identities. The date was not mentioned in only one prescription. The superscriptions were not properly mentioned in 16.2% prescriptions. The drugs were written directly in some of the prescriptions without superscriptions. The inscriptions were not clear in 15.3% prescriptions and the use of the generic names was less common (27.7%) than that of the brand names (72.7%). Abbreviations like HS, SOS, OD, and BID were commonly used. The subscriptions in 16% of the prescriptions were inadequate. The transcriptions in 2 5.3% of the prescriptions were inadequate. The instructions about refills or caution were not mentioned. The prescriber’s identity was without signature and the name of the prescriber in 4.7% of the prescriptions. The process of audit and feedback resulted in an overall statistically significant improvement in all the indicators of the prescription format between the baseline and the first and the second re-audits. A significant decline was observed in the percentage of the prescribers, which was deemed unidentifiable between the baseline audit and the subsequent re-audits [Table/Fig-2 and 3].

Comparative percentage improvement in the format of prescription

| Details of Prescription | First Month (All cycles) | Second Month (All cycles) | Third Month (All cycles) |

|---|

| Superscription | 83.85 | 88.9 | 95.8 |

| Inscription | 84.725 | 88 | 92.8 |

| Subscription | 83.975 | 88.8 | 92.3 |

| Transcription | 74.7 | 77.8 | 85.7 |

| Prescriber’s identity | 95.3 | 97.8 | 99.6 |

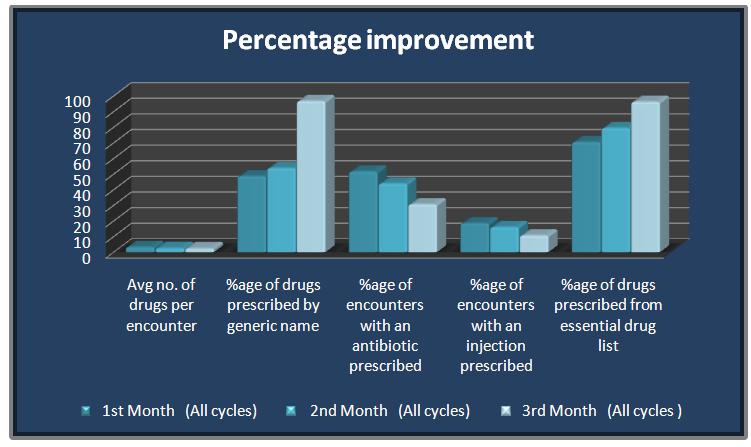

Similarly, the core drug indicators improved with every re-audit within each cycle, as well as the total percentage of the drug core indicators of all the cycles in the 2nd and 3rd months as compared to those of the baseline in the 1st month (p <0.05%). The average number of drugs per encounter was reduced from the baseline level of 3.35 to 2.5 in the third month. The percentage of the drugs which were prescribed by their generic names was increased to 97% from the initial baseline level of 48.7%. The percentages of antibiotics and injections which were prescribed had reduced to 31% and 11% respectively. The percentage of the drugs from the essential drug list had increased to 96% from its baseline level of 71% [Table/Fig-4 and 5].

Comparative improvement in WHO drug core indicators

| WHO Indicators | 1st Month (All cycles) | 2nd Month (All cycles) | 3rd Month |

|---|

| Average no. of drugs per encounter | 3.35 | 2.67 | 2.5 |

| Percentage of drugs prescribed by generic name | 48.675 | 53.868 | 96.825 |

| Percentage of encounters with an antibiotic prescribed | 51.7 | 44 | 30.7 |

| Percentage of encounters with an injection prescribed | 18.55 | 16.115 | 10.8 |

| Percentage of drugs prescribed from essential drug list | 70.525 | 79.55 | 96.325 |

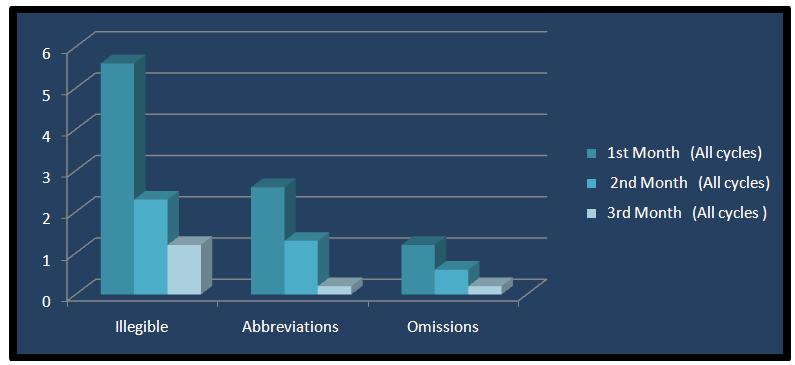

A significant decrease was noted in the percentage of the prescriptions, which was deemed to be unclear between the baseline and 682each subsequent re-audit [Table/Fig-6 and 7]. However, there was a decline in the improvement in the prescription behavior, which tended to reach the baseline levels when the prescription audits and the active feedback were discontinued after every cycle.

Comparative percentage improvement in legibility of prescriptions

| 1st Month (All cycles) | 2nd Month (All cycles) | 3rd Month (All cycles) |

|---|

| Illegible | 5.6 | 2.3 | 1.2 |

| Abbreviations | 2.6 | 1.3 | 0.2 |

| Omissions | 1.2 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

DISCUSSION

Clinical audits are gaining popularity in the health services as a first step in the quality improvement strategies and as a part of the accreditation processes. An audit is also an educational activity, which promotes high-quality care and which should be carried out regularly. It acts as a simple tool for evaluating the actual performance and in planning corrective actions to reduce the risk of medication errors [13].

Clinical audits are gaining popularity in the health services as a first step in the quality improvement strategies and as a part of the accreditation processes. An audit is also an educational activity, which promotes high-quality care and which should be carried out regularly. It acts as a simple tool for evaluating the actual performance and in planning corrective actions to reduce the risk of medication errors [13].

The published literature revealed that a vast majority of the papers were focused on the clinical audit ‘outcomes’ in terms of an improved adherence to the guidelines, and only few studies were found to show the impact of the clinical outcome on repeated cycles of reaudits.

A clinical audit is designed to measure the compliance with the standards of the proven clinical practice and to record the required and the documented changes in the clinical practice, which are shown by the re- audits. However, many audits do not reach the re- audit stage, and still fewer follow through to the repeat cycles of the audits. The components of an effective clinical audit should include a proper methodology and repeated cycles of audits to improve various clinical outcomes [14,15].

Our aim was to check the impact of the prescription audits and the active feedback on the prescription behaviour and how long this impact lasted. The percentage of rational prescriptions in terms of the formats increased successively in the subsequent re-audits in each cycle. There was also a significant decrease in the percentage of the prescriptions, which was unclear in the subsequent re-audits. Similar findings were documented in a previous study which was done [8].

In the same fashion, the WHO core drug indicators significantly improved in the successive re-audits. An improvement in the percentage of the encounters with the antibiotics which were prescribed, which was one of the core indicators, was also recorded in one previous study [8].

However, the improvement in the prescription behaviour was reversed when the prescription audits and the active feedback were discontinued after every cycle. This behaviour may be attributed to the fact that the prescribers were informed about the plan of the serial audits in advance. This bias can be removed by conducting surprise serial audits in the whole year, along with an active feedback and supervision.

CONCLUSIONS

Serial prescription audits and an active feedback definitely help in identifying the problems which are involved in the therapeutic decision making and they cause improvements in the prescription behaviour. At the same time, discontinuing the prescription audits begins to reverse the improvement in the prescription behaviour and this bias can be removed by doing surprise serial prescription audits.

Keeping in view that re-audits are not done in a majority of the prescription studies, the effective components of a clinical audit should include repeated cycles of the audits, along with its proper methodology, to improve various clinical outcomes.