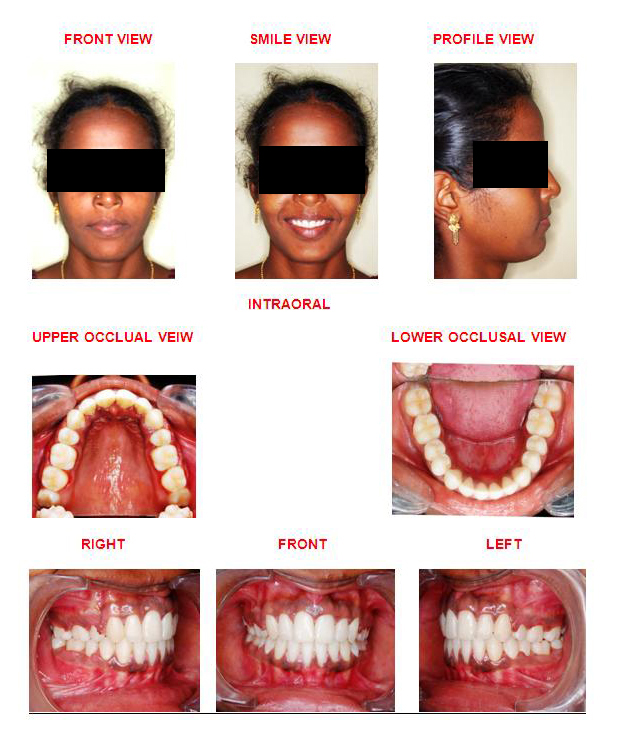

Since so many decades, various treatment modalities have been presented for the treatment for the class II, div 1 malocclusions. In recent times, we have seen enormously increasing numbers of young adults who desire the shortest, cost effective and a non surgical correction of Class II malocclusions and they accept dental camouflage as a treatment option to mask the skeletal discrepancy. This case report presents one such case of a 22 year old non-growing female who had a skeletal Class II, division 1 malocclusion with an orthognathic maxilla, a retrognathic mandible, a negative VTO and an overjet of 12mm, who did not want a surgical treatment. We considered the camouflage treatment by extracting the upper first premolars. Following the treatment, a satisfactory result was achieved with an ideal, static and a functional occlusion, facial profile, smile and lip competence and stability of the treatment results.

INTRODUCTION

Well aligned teeth not only contribute to the health of the oral cavity and the stomatognathic system, but they also influence the personality of the individual. A malocclusion compromises the health of the oral tissues and it can also lead to psychological and social problems. A class II, div I malocclusion is the most prevalent type of malocclusion which is being encountered in India. The classical features of the class II, div 1 malocclusion include a mild to severe class II skeletal base with an Angles class II molar relation and class II canine and incisor relations, proclined maxillary incisors and an increased overjet and it generally has a convex profile with incompetent lips.

The treatment planning of the class II, non growing patients is challenging and controversial. A class II malocclusion is commonly seen in the orthodontic practice, with a frequency of 14% among children who are between 12 and 14 years of age [1]. Over the last decade, increasing numbers of adults have become aware of the orthodontic treatment and are demanding a high-quality treatment with an increased efficiency and reduced costs, in the shortest possible time [2]. A class II, div I malocclusion is the most prevalent type of malocclusion in India. Its management frequently involves the use of a myofunctional appliance in growing patients, but in the non growing, adult patients, it usually includes an orthognathic surgery or a selective removal of the permanent teeth, with a subsequent dental camouflage to mask the skeletal discrepancy. For the correction of the class II malocclusions in non-growing patients, the extractions can involve 2 maxillary premolars or 2 maxillary and 2 mandibular premolars [3].

The extraction of only 2 maxillary premolars is generally indicated when there is no crowding or cephalometric discrepancy in the mandibular arch [4,5]. The extraction of 4 premolars is indicated primarily for crowding in the mandibular arch, a cephalometric discrepancy, or a combination of both, in growing patients [5–7]. Recent studies have shown that the patient satisfaction with a camouflage treatment is similar to that which is achieved with a surgical mandibular advancement [8] and that the treatment with two maxillary premolar extractions gives a better occlusal result than the treatment with four premolar extractions [9].

CASE REPORT

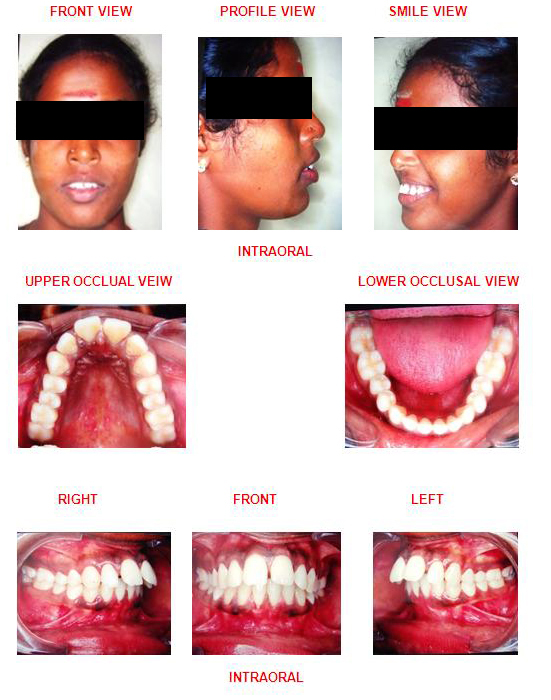

A 22 years old female patient reported to the private clinic with the chief complaint of proclined upper front teeth with spacing. She gave a history of thumb sucking as a child.

An extra oral examination revealed a mesocephalic head shape with a mesoproscopic facial form. The patient had an increased visibility of the upper anterior teeth. The profile of the patient was convex, with a posterior facial divergence. The nasolabial angle was acute, with potentially competent lips. The patient showed a retruded mandible with a horizontal growth pattern and she had a negative VTO.

Her intraoral examination revealed that the patient had a full cusp, Class II molar and canine relationship, a “V shaped” arch form and excessively proclined maxillary incisors with an overjet of 12mm and 4mm of spacing in the upper anteriors, with an associated palatal impingement of the lower incisors.

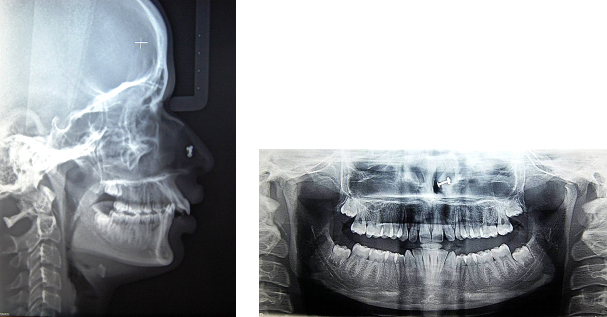

A cephalometric analysis concluded that the maxilla was normal and that the mandible was retrognathic. A panoramic radiograph showed that the maxillary and the mandibular, partially erupted, third molars were present.

There was no evidence of restorations, caries or any other pathology. Normal alveolar bone levels was presant. The dental components showed protrusion of the upper incisors.

The study model analysis confirmed the arch length and a tooth material discrepancy of 14mm tooth material excess in the maxilla and 3 mm tooth material excess in the mandible. According to the total space analysis, 11mm of space was required in the maxilla and 2 mm of space was required in the mandible.

A surgical approach to the treatment was not desired by the patient, and although the anterio-posterior jaw discrepancy was severe, the selective extraction of two permanent, maxillary, first premolar teeth was considered to be acceptable.

Treatment goals:

Obtaining a good facial balance

Obtaining an optimal static and a functional occlusion and stability of the treatment results.

The treatment objectives which would lead to an overall improvement of the hard- and soft-tissue profile and the facial aesthetics were:

To correct the upper incisor proclination

To achieve an ideal overjet and an ideal over bite

To achieve a lip competence.

To achieve a flat occlusal plane.

To achieve an adequate functional occlusal intercuspation with a Class II molar and a Class I canine relationship.

The molar positions, the arch width, and the midlines needed to be maintained

Treatment plan:

Extraction of the maxillary first premolars.

Alignment and leveling of the arches.

Leveling the curve of Spee without increasing the arch perimeter

Closing the extraction space by T-loop enmass retraction.

Final consolidation of the space and

Settling of the occlusion.

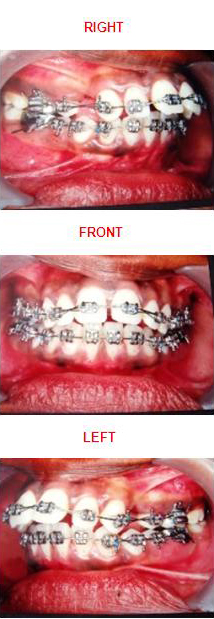

The maxillary first premolars were extracted and the patient underwent a fixed orthodontic mechanotherapy with a preadjusted edgewise appliance (0.022-inch slot). An initial 0.016-inch round nickel titanium arch wire was used for the levelling and the alignment of both the arches. After 6 weeks of treatment, the upper second molars were banded to prevent anchor loss during the retraction. The upper and lower 0.016 x 0.022-inch reverse curve NiTi were placed, which was later followed by the placement of 0.017 x 0.025-inch nickel titanium wires at 12 weeks. At the end of 16 weeks, enough leveling and aligning had occurred to place the upper and lower 0.019 x 0.025-inch SS wires.

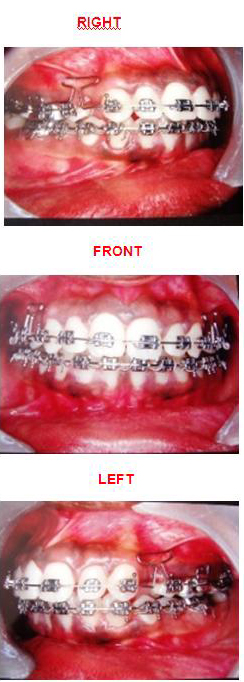

At the 20th week, enmass retractions of the six anterior teeth were carried out by using a T –loop canine retractor. A step wise activation of 1-2 mm was done every month to close the extracted tooth space.

At the same time, utmost care was taken to prevent an undesirable mesial drift of the maxillary molars. As the camouflage treatment with 2 premolar extractions requires anchorage conservation and in order to reinforce our anchorage, we used an upper second molar banding.

After the closure of the 1st premolar extraction space, the extraction site was stabilized with a figure of eight ligation between the molars. A 0.019 x 0.025 nickel titanium arch wire was placed to level the arch, followed by the placement 0.014 stainless steel wires for the occlusal settling, following which the case was debonded and a fixed upper and lower lingual bonded retainer was given.

DISCUSSION

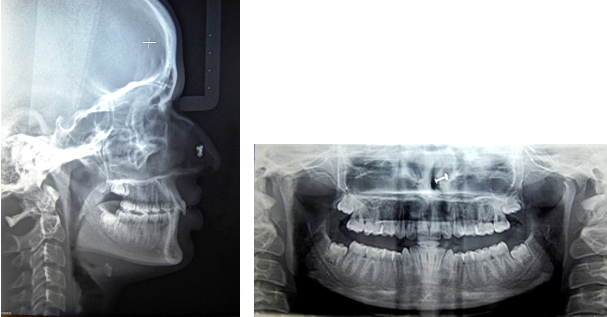

The goal of dental camouflage is to correct the skeletal relationships by orthodontically repositioning the teeth in the jaws, so that there is an acceptable dental occlusion and an aesthetic facial appearance. The possibilities for the treatment in this patient were to displace the teeth which were relative to their supporting bone and to compensate for the underlying jaw discrepancy. The displacement of the teeth, as in the retraction of the protruding incisors, is often termed as camouflage. In this case, a surgical treatment was rejected by the patient and it was decided to hide the skeletal discrepancy by extracting the maxillary premolars and retracting the anterior teeth to improve the profile of the patient and to obtain a proper functional occlusion. This resulted in dental and accompanying soft tissue profile changes and there was no skeletal change [Table/Fig-1,2,3,4, 5,6 & 7].

| VARIABLE | PRE-TREATMENT | POST-TREATMENT |

|---|

| SKELETAL |

| SNA | 800 | 800 |

| SNB | 740 | 740 |

| ANB | 60 | 60 |

| WITS (AO-BO) | 6 mm | 6 mm |

| GO-GN-SN | 350 | 350 |

| DENTAL |

| UI – SN | 1220 | 1040 |

| UI – NA | 14 mm/420 | 4 mm/230 |

| LI – NB | 5 mm/230 | 6 mm/260 |

| IMPA | 970 | 1000 |

| OVERJET | 12 mm | 2 mm |

| SOFT-TISSUE |

| NASO LABIAL ANGLE | 810 | 1010 |

| U LIP – S LINE | +5 mm | 0 mm |

| L LIP – S LINE | + 2 mm | 0 mm |

Post –Treatment Extraoral

Pretreatment Lateral Cephalogram &Opg

Posttreatment Lateral Cephalogram & Opg

The treatment of an adult Class II patient requires a careful diagnosis and a treatment plan which involves aesthetic, occlusal, and functional considerations [10]. The indications for the extractions in the orthodontic practice have historically been controversial [11–13]. The premolars are probably the most commonly extracted teeth for orthodontic purposes, as they are conveniently located between the anterior and the posterior segments. Variations in the extraction sequences, which include the upper and the lower first or the second premolars, have been recommended by different authors for a variety of reasons [14–19]. The treatment of the complete Class II malocclusions by extracting only 2 maxillary premolars requires an anchorage to avoid a mesial movement of the posterior segment during the retraction of the anterior teeth.

To reinforce the anchorage, a second molar banding is done to prevent the mesial movment of the molars. The treatment planning decisions depend on a cost/benefit ratio [20].

The orthodontic treatment goals usually include obtaining a good facial balance and an optimal static and functional occlusion and stability of the treatment results [21–22]. Whenever possible, all should be attained. In some instances, however, the ultimate objectives cannot be reached because of the severity of the orthodontic problems [22]. To provide an optimal facial balance, a 4-premolar extraction protocol in a complete Class II malocclusion would be the best option. However, because of the patients’ advanced ages and their poor compliance attitudes, a 2-premolar extraction protocol can provide greater benefits and thus it can be selected. Various studies have also shown that the extractions of premolars, if they are undertaken after a thorough diagnosis, lead to a positive profile change [23–26].

CONCLUSION

The camouflage treatment of the Class II malocclusion in adults is challenging and it requires a high quality individualized technique. Extractions of the premolars, if they are undertaken after a proper diagnosis, lead to remarkable profile changes and satisfactory facial aesthetics.

A well chosen individualized treatment plan which is undertaken with sound biomechanical principles and an appropriate control of the orthodontic mechanics to execute the plan, is the surest way to achieve predictable results with minimal side effects. The correction of the malocclusion was achieved, with a notable improvement in the patient aesthetics and self-esteem. The patient satisfaction with a camouflage treatment is similar to that which is achieved with a surgical orthodontic approach.

[1]. Emrich RE, Brodie AG, Blayney JR, Prevalence of Class I, Class II, and Class III Malocclusions (Angle) in an Urban Population - An Epidemiological StudyJ Dent Res. 1965 44:947-53. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Khan RS, Horrocks EN, A study of adult orthodontic patients and their treatmentBr J Orthod 1991 18(3):183-94. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Cleall JF, Begole EA, Diagnosis and treatment of Class II Division 2 malocclusionAngle Orthod 1982 52:38-60. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Strang RHW, Tratado de ortodoncia. Buenos Aires: Editorial Bibliogra´ficaArgentina 1957 560-70:657-71. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Bishara SE, Cummins DM, Jakobsen JR, Zaher AR, Dentofacial and soft tissue changes in Class II, Division 1 cases treated with and without extractionsAm J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1995 107:28-37. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Rock WP, Treatment of Class II malocclusions with removable appliances. Part 4. Class II Division 2 treatmentBr Dent J. 1990 168:298-302. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Arvystas MG, Nonextraction treatment of Class II, Division 1 malocclusionsAm J Orthod 1985 88:380-95. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Mihalik CA, Proffit WR, Phillips C, Long-term follow up of Class II adults treated with orthodontic camouflage: A comparison with orthognathic surgery outcomesAm. J. Orthod 2003 123:266-78. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Janson G, Brambilla AC, Henriques JFC, de MR, Class II treatment success rate in 2- and 4-premolar extraction protocolsAm. J. Orthod 2004 125(4):472-79. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Kuhlberg A, Glynn E, Treatment planning considerations for adult patientsDent.Clin. N. Am. 1997 41:17-28. [Google Scholar]

[11]. Case CS, The question of extraction in orthodontiaAmerican Journal of Orthodontics 1964 50:660-91. [Google Scholar]

[12]. Case CS, The extraction debate of 1911 by Case, Dewey, and Cryer. Discussion of Case: the question of extraction in orthodontiaAmerican Journal of Orthodontics 1964 50:900-12. [Google Scholar]

[13]. Tweed C, Indications for the extraction of teeth in orthodontic procedureAmerican Journal of Orthodontics 1944 30:405-28. [Google Scholar]

[14]. Staggers JA, A comparison of results of second molar and first premolar extraction treatmentAmerican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 1990 98:430-36. [Google Scholar]

[15]. Luecke PE, Johnston LE, The effect of maxillary first premolar extraction and incisor retraction on mandibular position: testing the central dogma of ‘functional orthodontics’American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 1992 101:4-12. [Google Scholar]

[16]. Proffit WR, Phillips C, Douvartzidis N, A comparison of outcomes of orthodontic and surgical-orthodontic treatment of Class II malocclusion in adultsAmerican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 1992 101:556-65. [Google Scholar]

[17]. Paquette DE, Beattie JR, Johnston LE, A long-term comparison of non extraction and premolar extraction edgewise therapy in ‘borderline’ Class II patientsAmerican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 1992 102:1-14. [Google Scholar]

[18]. Taner-Sarısoy L, Darendeliler N, The influence of extraction treatment on craniofacial structures: evaluation according to two different factorsAmerican Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 1999 115:508-14. [Google Scholar]

[19]. Basciftci FA, Usumez S, Effects of extraction and non extraction treatment on Class I and Class II subjectsAngle Orthodontist 2003 73:36-42. [Google Scholar]

[20]. Shaw W, O’Brien K, Richmond S, Brook P, Quality control in orthodontics: risk/benefit considerationsBr Dent J. 1991 170:33-37. [Google Scholar]

[21]. Bishara S, Hession T, Peterson L, Longitudinal soft-tissue profile changes: a study of three analysesAm J Orthod 1985 88:209-23. [Google Scholar]

[22]. Alexander RG, Sinclair PM, Goates LJ, Differetial diagnosis and treatment planning for adult nonsurgical orthodontic patientAm J Orthod 1986 89:95-112. [Google Scholar]

[23]. Moseling K, Woods MG, Lip curve changes in females with premolar extraction or non-extraction treatmentAngle Orthod 2004 74:51-62. [Google Scholar]

[24]. Ramos AL, Sakima MT, Pinto AS, Bowman SJ, Upper lip changes correlated to maxillary incisor retraction – a metallic implant studyAngle Orthod 2005 75:499-505. [Google Scholar]

[25]. Conley SR, Jernigan C, Soft tissue changes after upper premolar extraction in Class II camouflage therapyAngle Orthod 2006 76:59-65. [Google Scholar]

[26]. Tadic N, Woods MG, Incisal and soft tissue effects of maxillary premolar extraction in Class II treatmentAngle Orthod 2007 77:808-16. [Google Scholar]