Central Nervous System Cryptococcosis among a Cohort of HIV Infected Patients from a University Hospital of North India

Chaitanya Nigam1, Rupam Gahlot2, Vikas Kumar3, Jaya Chakravarty4, Ragini Tilak5

1 Service Senior Resident, Department of Microbiology, IMS, BHU, Varanasi, India

2 Junior Resident, Department of Microbiology, IMS, BHU, Varanasi, India

3 Service Senior Resident, Department of Microbiology, IMS, BHU, Varanasi, India

4 Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, IMS, BHU, Varanasi, India

5 Associate Professor, Department of Microbiology, IMS, BHU, Varanasi, India

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Chaitanya Nigam, Service Senior Resident, Department of Microbiology, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi- 221005 India.

Phone: +91 – 9236606095,

E-mail: cn3580@googla.com

Background

Cryptococcus neoformans is a ubiquitous encapsulated yeast that causes significant infections which range from asymptomatic pulmonary colonization to the life threatening meningoencephalitis, especially in immunocompromised individuals. Cryptococcal meningitis is one of the AIDS-defining illnesses. Recent data have indicated that, the incidence of the cryptococcal infection is high in developing countries like India. We conducted this study to find out the incidence of cryptococcosis in this area.

Material and Methods

The Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) specimens were collected from known HIV positive cases that had a clinical diagnosis of meningitis and they were processed by standard microbiological procedures. The cryptococcal isolates were identified by microscopy, their cultural characteristics, sugar assimilation and by the hydrolysis of urea.

Results

The incidence of cryptococcal meningitis was 12.9%. All the strains were susceptible to amphotericin B, fluconazole, itraconazole and voriconazole.

Conclusion

The cryptococcal infection should be suspected in all cases of meningitis, especially among HIV infected persons. An early diagnosis and treatment may alter the prognosis of these patients and hence, an examination of the CSF for cryptococcosis should be considered in all the HIV infected persons who have the symptoms of meningitis.

Cryptococcal meningitis, HIV, Latex agglutination, India ink

Introduction

Cryptococcal meningitis is an opportunistic infection which occurs in immunocompromised patients. It is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans, an encapsulated yeast, which represents the most common cause of the fungal infections of the central nervous system among these patients [1–3]. The incidence of cryptococcal meningitis has increased in the recent years, both in the HIV-positive and negative patients [4]. Cryptococcal meningitis may be the presenting manifestation of AIDS. The most common sites of occurrence of this infection are the central nervous system and the lungs [5–7]. The C. neoformans infection occurs after the inhalation of this organism through the respiratory tract. This organism disseminates hematogenously and it has a propensity to localize in the central nervous system, causing meningitis/meningoencephalitis [8,9]. Although the incidence of cryptococcal meningitis has declined in the HIV patients who undergo anti-retroviral therapy, cryptococcal disease remains a leading cause of mortality in the developing world [10]. The clinical signs and symptoms of C. neoformans meningitis are indistinguishable from those of many other causes of meningitis, especially tubercular meningitis. The early cases with no symptoms which are referable to the Central Nervous System (CNS) may have a positive culture of the CSF, with no other abnormality in the fluid [11]. An early diagnosis of the cryptococcal infection is therefore necessary for its appropriate management. The present work is a prospective study of suspected cases of cryptococcal meningitis among HIV infected patients during a period of 1 year.

Material and Methods

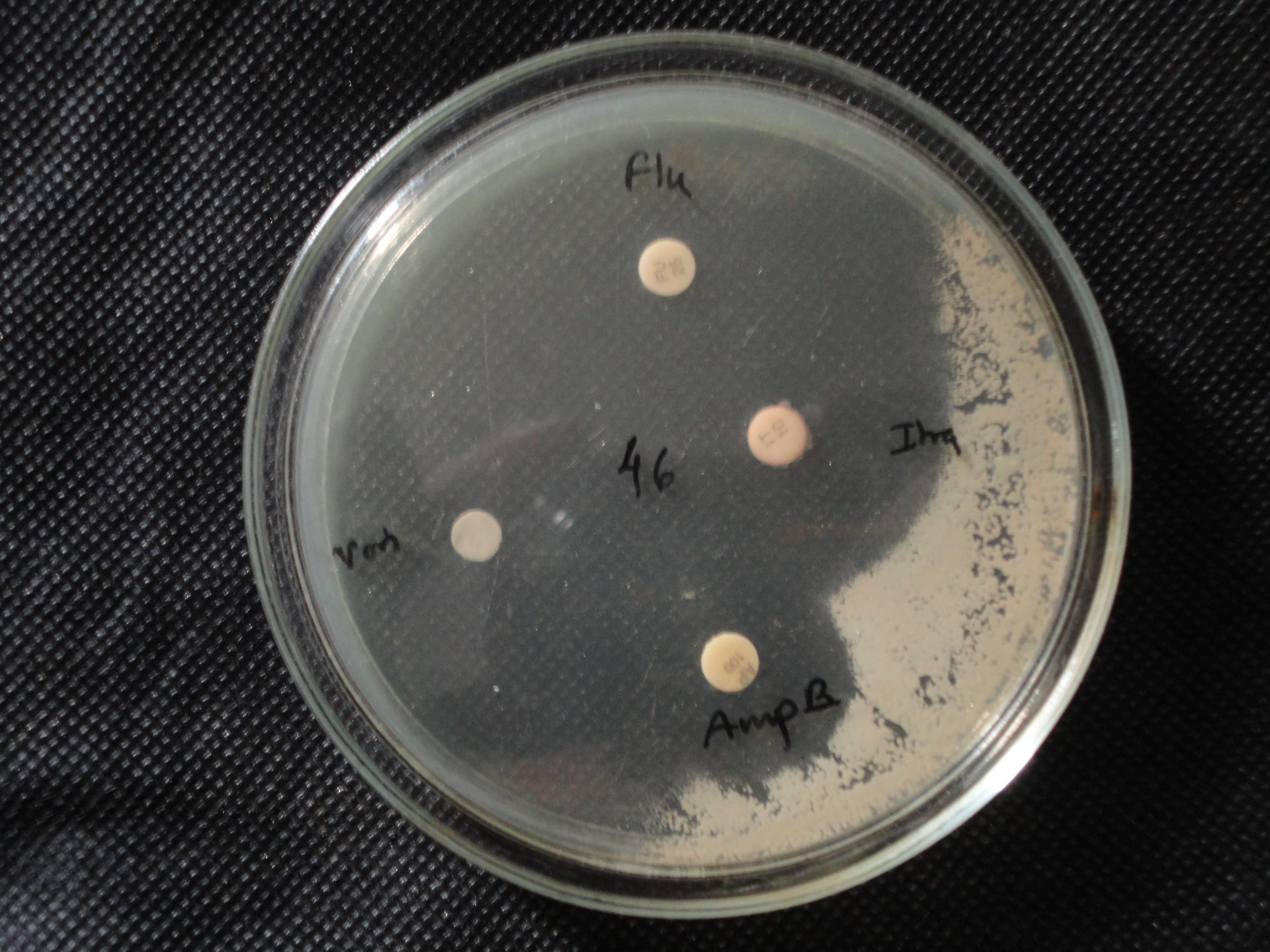

All the CSF samples from HIV positive, clinically suspected meningitis patients, which were received for microbiological analysis, constituted the study material during March 2009 to February 2010. The CSF was collected after taking an informed written consent from the patients. The details of the demographic profile of the patients (viz. name, age, sex, address, date of admission and date of discharge/death) were recorded. After the preliminary microscopic examination (India ink staining and gram staining) and antigen detection (Remel Crypto-LA test kit) [Table/Fig-1], all the samples of CSF were processed for routine microbiological culture on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar, which was incubated at 25°C in a BOD incubator and processed according to a predetermined protocol which was based on the presence of any visible growth. The fungal cultures were followed for 4 weeks. The colonies of C.neoformans were identified, based on their yeast like colony morphology, the presence of spherical yeast cells without hyphae/psesudohyphae on microscopy, a negative germ tube test, a positive urease test [Table/Fig-2] and the assimilation of sugars viz. inositol, lactose, cellobiose, melibiose and trehalose. The culture isolates were sent to SGPGI, Lucknow for biotyping. The anti-fungal susceptibility was determined by the disk diffusion method [12] [Table/Fig-3].

Crypto LA test: well 4 -showing positive agglutination whereas well 1,2,3,5,6 showing negative test results

Urease test: pink-positive and yellow-negative

Antifungal susceptibility test, strain is susceptible to all antifungals used, showing zone of clearing around discs

Results

A total of 132 consecutive, non-repetitive CSF samples from HIV infected patients with a clinical diagnosis of chronic meningitis were screened during a period of 1 year. Fourteen (10.6%) were found to be positive by the India ink examination, 20 (15.1%) were found to be positive by antigen detection and 17 (12.9%) of them were found to be culture positive for Cryptococcus, which were further identified by one or more confirmatory tests [Table/Fig-4]. The ages of the patients who were positive for cryptococcal meningitis ranged from 26 to 55 years with a mean age of 40.35 years; the male: female ratio was 16:1. In our study, the incidence of cryptococcal meningitis was 12.9%, among which 94.11% (16/17) were C.neoformans var. neoformans and 5.88% (1/17) were C.neoformans var. gattii. All the strains were susceptible to Amphotericin B, fluconazole, Itraconazole and Voriconazole. The mortality rate was 15% and the average hospital stay was 21 days.

Comparison of different tests for diagnosis of Cryptococcal meningitis

| India ink | Culture | Crypto LA |

|---|

| Positive | 14 | 17 | 20 |

| Negative | 118 | 115 | 112 |

| Total | 132 | 132 | 132 |

Discussion

The incidence of cryptococcal meningitis has increased after the pandemic of AIDS and it varies from place to place [13]. The incidence rate in our study was 12.9%, which was comparable to the findings of other north Indian studies [14] but it differed from the reports from south India [13,15,16] and other parts of the world [17,18]. The age range of the patients in our study population was very diverse (19-60 years) and there was a male predominance. The mean age of the patients who were positive for cryptococcal meningitis was 38.86 (40.35years), with a range of 19-60 (26-55 years). Most of the cases belonged to the age group of 30-60years [13,17,15] [Table/Fig-5]. There is a difference in the incidence and the prevalence of cryptococcal meningitis in males and females in different countries and in different regions in the same country. In our study, the ratio of its incidence among males and females was 16:1 and the reason may have been different exposures as has been explained in other studies rather than different susceptibilities [15], which was comparable to the findings of other studies [12,19,20]. The sensitivity of the Crypto-LA test was more than 100%, which detected 20 (15%) cases, but three of these cases did not show any growth on culture. Only 14 (10.6%) cases were India ink positive and the sensitivity was 82.35%, which was similar to the findings of other studies [13,17] and all of them were culture positive too [Table/Fig-4]. Among all the culture positive cases, 16 (94.11%) were Cryptococcus neoformans var. neoformans and only 1 (5.88%) was Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii. The isolation of C. gattii reflects the changing pattern of cryptococcosis [21,22]. The average hospital stay was about 3 weeks (21 days) as they could be susceptible to various nosocomial infections during this period and this much abstinence from work was really cumbersome for the poor people. The case fatality rate in this study was 17.6%, which differed from the findings of the studies which were conducted by P Mwaba et al., and Shaikh Mohammed et al., which showed 100% and 32% fatality rates respectively [23,20]. All the culture positive strains were tested for their anti-fungal susceptibilities. All the strains were equally susceptible to all the four anti-fungal drugs (Amphotericin B, Fluconazole, Itraconazole and Voriconazole) which were used to do their in vitro antifungal susceptibility testing by the disk diffusion method [Table/Fig-6].

Distribution of study population

| Age | Sex | Culture | Total |

|---|

| Positive | Negative |

|---|

| <30years | Male | 2 | 25 | 27 |

| Female | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 30-60 years | Male | 13 | 68 | 81 |

| Female | 2 | 13 | 15 |

| >60 years | Male | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Female | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | | 17 | 115 | 132 |

Comparison of Culture and Crypto LA

| Crypto LA |

|---|

| Culture | Negative | Positive | Total |

|---|

| Negative | 112 | 3 | 115 |

| Positive | 0 | 17 | 17 |

| Total | 112 | 20 | 132 |

Conclusion

The CSF examination (gram staining, India ink staining) employs simple and easy techniques and this can be performed in any clinical microbiology laboratory. The incorporation of antigen detection tests provides additional benefit due to their high sensitivities. Repeated attempts to demonstrate yeast cells in microscopy and culture on lumbar puncture specimens both pre and post treatment are an important requirement in the diagnosis and the detection of their resistance. We believe that awareness among clinicians and microbiologists will go a long way in arriving at a definite clinical and aetiological diagnosis of cryptococcosis, which would have otherwise been missed or the patients would have undergone treatment for tuberculosis.

[1]. Khanna N, Chandramuki A, Desai A, Ravi V, Cryptococcal infections of the central nervous system: An analysis of the predisposing factors, laboratory findings and the outcome in patients from south India, with a special reference to the HIV infectionJ Med Microbiol 1996 45:376-9. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Khanna N, Chandramuki A, Desai A, Ravi V, Santosh V, Shankar SK, Cryptococcosis in the immunocompromized host with a special reference to AIDSIndian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2000 42:311-5. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Oursler KA, Moore RD, Chaisson RE, The risk factors for Cryptococcal meningitis in HIV-infected patientsAIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 1999 15:625-31. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Gottfredsonn M, Fungal meningitisSemin Neurol 2000 20:307-22. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Levitz SM, The ecology of Cryptococcus neoformans and the epidemiology of CryptococcosisRev Infect Dis 1991 13:1163-9. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Perfect JR, Casadevall A, CryptococcosisInfect Dis Clin North Am 2002 16:837-74. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Pappas PG, Perfect JR, Cloud GA, Larsen RA, Pankey GA, Lancaster DJ, Cryptococcosis in human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients in the era of the effective azole therapyClin Infect Dis 2001 33:690-9. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Igel HJ, Bolande RP, The humoral defense mechanisms in Cryptococcosis: the substances in normal human serum, saliva, and cerebrospinal fluid which affect the growth of Cryptococcus neoformansJ Infect Dis 1966 116(1):75-83. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Diamond RD, May JE, Kane MA, Frank MM, Bennett JE, The role of the classical and the alternate complement pathways in the host defenses against the Cryptococcus neoformans infectionJ Immunol 1974 112(6):2260-70. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Jarvis JN, Harrison TS, HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitisAIDS 2007 21(16):2119-29. [Google Scholar]

[11]. Kwon-Drung KJ, Bennett J E, Medical Mycology Lea and Febiser 1992 :396-9. [Google Scholar]

[12]. CLSIA Method for the Antifungal Disk Diffusion Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Proposed Guideline 2003 Pennsylvania, USACLSICLSI document M44-A [ISBN 1-56238-488-0] [Google Scholar]

[13]. Manoharan G, Padmavathy BK, Vasanthi S, Gopalte R, Cryptococcal meningitis among HIV-infected patientsIndian J Med Microbiol 2001 19:157-8. [Google Scholar]

[14]. Prasad KN, Agarwal J, Nag VL, Verma AK, Dixit AK, Ayyagari A, The cryptococcal infection in patients with clinically diagnosed meningitis in a tertiary care centerNeurol India 2003 51:364-66. [Google Scholar]

[15]. Baradkar V, Mathur M, De A, Kumar S, Rathi M, Prevalence and clinical presentation of Cryptococca meningitis among HIV seropositive patientsIndian J Sex Transm Dis 2009 30:19-22. [Google Scholar]

[16]. Lakshmi V, Sudha T, Teja VD, Umabala P, Prevalence of central nervous system cryptococossis in Human Immunodeficiency Virus reactive hospitalized patientsIndian J Med Microbiol 2007 25:146-9. [Google Scholar]

[17]. Wenqi W, The clinical manifestation of AIDS with cryptococcal meningitisChinese Medical Journal 2001 114(8):841-3. [Google Scholar]

[18]. Roses SC, Agania A, Eruns M, Meningitis subjects with the HIV infectionBull Soc Pathol Exot 1999 92(1):23-6. [Google Scholar]

[19]. Bogaerts J, Roueroy D, Taelman H, Kagame A, Aziz MA, Swinned VJ, AIDS associated Cryptococcal meningitis in Rwanda (1983-92) Epidemiological and diagnostic featuresJ infect 1999 39(3):329-31. [Google Scholar]

[20]. Shaikh Mohammed S Aslam, Chandrasekhara P, Study of Cryptococcal meningitis in HIV seropositive patients in a tertiary care centreJIACM 2009 10(3):110-15. [Google Scholar]

[21]. Karstaedt AS, Crewe-Brown HH, Dromer F, Cryptococcal meningitis caused by Cryptococcus neoformans var. gattii, serotype C, in AIDS patients in Soweto, south AfricaMed Mycol 2002 40:7-11. [Google Scholar]

[22]. Chaturvedi S, Dyavaiah M, Larsen RA, Chaturvedi V, Cryptococcus gattii in the AIDS patients in southern CaliforniaEmerg Infect Dis 2005 11:1686-92. [Google Scholar]

[23]. Mwaba P, Mwansa J, Chintu C, Pobee J, Scarborough M, Portsmouth The clinical presentation, natural history, and the cumulative death rates of 230 adults with primary cryptococcal meningitis among Zambian AIDS patients who were treated under local conditionsPostgrad Med J 2001 77(914):769-73. [Google Scholar]