Case Report

A 42-year-old female patient presented with chief complaints of fever, palpitations, breathlessness (grade II), weight loss and fatigability for the past two months. She reported an evening rise in temperature, which responded to medications, and was not associated with chills, rigours, burning micturition, cough with expectoration, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, or skin infections. There was no recent travel or vaccination history, nor any co-morbidities.

At the time of admission, the patient was conscious, oriented, and presented with pallor and clubbing. Her vital signs at the time of admission were as follows: temperature 99.6°F, a heart rate of 108 beats per minute, blood pressure of 110/70 mmHg, respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute, and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 15 (E4V5M6). Her left brachial and radial pulse were not felt. The capillary blood glucose level was 120 mg/dL.

Auscultation revealed a pan-systolic murmur in mitral area. Other systemic examinations were normal. Several diagnostic investigations were conducted to assess the patient’s condition comprehensively and were found to be within normal range. Her Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) (110 mm at 1 hr) and C-reactive Protein (CRP) (72.34 mg/L) were raised [Table/Fig-1]. In suspect of bacteraemia, blood samples were sent for culture.

Laboratory investigations done for the patient.

| Test | Results | Normal range | Units |

|---|

| Complete blood profile |

| Total counts (WBC) | 8100 | 4000-11000 | cells/mm3 |

| Neutrophils | 76.2 | 40-75 | % |

| Lymphocytes | 16.8 | 20-45 | % |

| Eosinophils | 0.9 | <6 | % |

| Basophils | 0.3 | <2 | % |

| Monocytes | 5.8 | 2-10 | % |

| Total RBC count | 3.10 | 3.8-4.8 | cells/mm3 |

| Packed Cell Volume (PCV) | 23.0 | 36-46 | % |

| MCV | 74.2 | 83-101 | fL |

| MCH | 24.0 | 27-32 | pg |

| MCHC | 32.3 | 31.5-34.5 | % |

| Haemoglobin (Hb) | 7.4 | 12-15 | g/dL |

| RDW-CV | 22.2 | 11.5-14.5 | % |

| Platelets | 201000 | 150000-450000 | mm3 |

| Haematological profile | Microcytic hypochromic RBCs, with a moderate degree of anisocytosis along with a few elongated cells- microcytic hypochromic anaemia |

| Renal function tests |

| Blood urea | 11 | 15-45 | mg/dL |

| Serum creatinine | 0.45 | 0.5-1.1 | mg/dL |

| Anaemia profile |

| Iron | 34.81 | 33-193 | μg/dL |

| TIBC | 174.31 | 250-450 | μg/dL |

| UIBC | 139.5 | 120-470 | μg/dL |

| Transferrin saturation | 19.9 | 14-50 | % |

| Liver function tests |

| Total protein | 7.3 | 6-8.3 | g/dL |

| Albumin | 3.2 | 3.7-5.3 | g/dL |

| Globulin | 4.1 | 2.3-3.6 | g/dL |

| A/G ratio | 0.8:1 | - | - |

| Total bilirubin | 0.5 | 0.2-1 | mg/dL |

| Direct bilirubin | 0.2 | <0.2 | mg/dL |

| Indirect bilirubin | 0.3 | 0.2-0.6 | mg/dL |

| AST (SGOT) | 16 | <31 | U/L |

| ALT (SGPT) | 13 | <31 | U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 126 | 60-170 | U/L |

| Urine routine |

| Reaction | Acidic | - | - |

| pH | 6.0 | - | - |

| Albumin and sugar | Nil | - | - |

| Pus cells | 6-8 | - | - |

| Epithelial cells | 3-4 | - | - |

| RBC, casts, crystals | Nil | - | - |

| Bacteria | + | - | - |

| Electrolytes |

| Sodium (Na+) | 126 | 135-145 | mEq/L |

| Potassium (K+) | 4.2 | 3.5-5.4 | mEq/L |

| Chloride (Cl-) | 98 | 98-107 | mEq/L |

| ESR (1 hr) | 110 | 1-12 | Mm/hr |

| CRP | 72.34 | - | - |

| Microbiology |

| Parasites | Not seen in the smear |

| Stool for occult blood, ova, cyst, trophozite | Negative |

| Non reactive for HIV antibodies, negative for HBsAg (HBsAg rapid card test) and non reactive for HCV antibody (HCV rapid card test). |

| Chest X-ray (PA) | The presence of bilateral rudimentary cervical ribs, while the rest of the bony cage appeared normal. No signs of mediastinal widening were observed, and the lungs appeared normal. The size and shape of the heart were within normal limits, with clear phrenic sinuses |

| 2D ECHO | A mildly dilated left atrium and concentric left ventricle hypertrophy, with no regional wall motion abnormalities. Left ventricular systolic and diastolic function, indicated by a normal ejection fraction of 58% with severe eccentric mitral regurgitation, primarily posteriorly directed, was noted. Diastolic dysfunction was noted. There was trivial mitral and aortic tricuspid regurgitation and mild tricuspid regurgitation with a Pulmonary Artery Systolic Pressure (PASP) of 40 mmHg |

| CT aortogram | Normal calibre and adequate contrast opacification of the aorta and its branches, with no signs of wall thickening, vessel wall calcification, or aneurysmal dilatation/dissection. The abdominal aorta, and bilateral common iliac arteries showed normal opacification without stenosis |

| USG abdomen ad pelvis | Presence of right grade I hydronephrosis |

WBC: White blood cells; RBC: Red blood cells; MCV: Mean corpuscular volume; MCH: Mean corpuscular haemoglobin; MCHC: Mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration; RDW-CV: Red blood cell distribution width; TIBC: Total iron-binding capacity; UIBC: Unsaturated iron binding capacity; A/G: Albumin/globulin; SGOT: Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; SGPT: Serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; PA: Postero-anterior; ECHO: Echocardiogram; CT: Computed tomography; USG: Ultrasonography

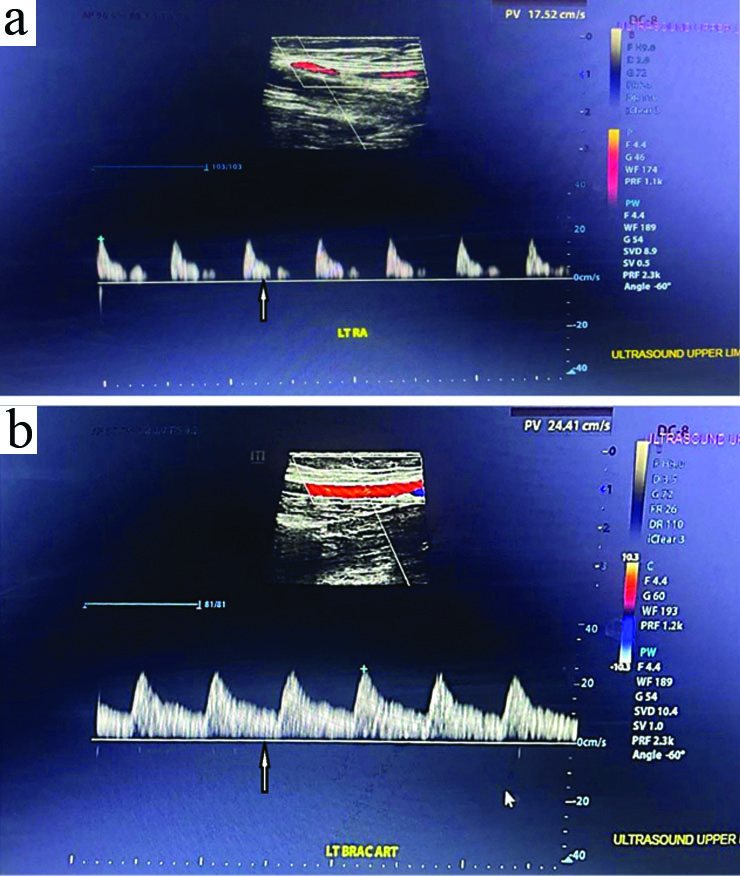

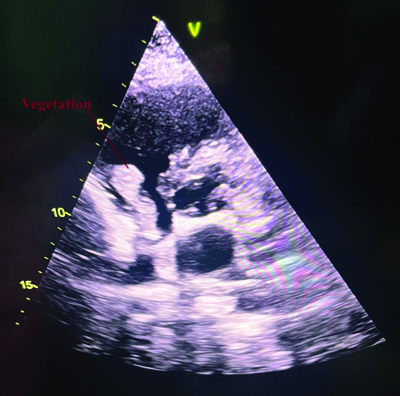

Upper limb arterial Doppler revealed biphasic waveforms and mildly reduced flow in the left radial and brachial arteries, with no evidence of thrombosis, which was not felt during the examination [Table/Fig-2]. The Two Dimensional (2D) Echocardiogram (ECHO) revealed freely mobilising echogenic foci attached to posterior wall of right atrium above the tricuspid valve, measuring as body (20×19 mm) and stalk (5 mm) [Table/Fig-1]. Also, a highly mobile, dependent and hyperechoic mass was attached to both posterior Mitral Leaflet (ML), predominantly in the anterior ML, measuring 7×7 mm, suggestive of a healed vegetation. No pericardial effusion was observed [Table/Fig-3] [Video-1]. Thus, a diagnosis was made as IE and immediately initiated i.v. Injection (Inj.) gentamycin 1.2 mL (9 days) and Inj. ceftriaxone (2 gm) for 7 days. A normal Computed Tomography (CT) aortogram [Table/Fig-1] [Video-2] and ultrasonography revealed grade II/III hydroureteronephrosis.

Vascular colour doppler study of a) Left radial artery; b) Left brachial artery. An ultrasound upper limb arterial Doppler, which revealed biphasic waveforms and mildly reduced flow in the left radial and brachial arteries with no evidence of thrombosis (indicated by the arrow).

2D Echocardiogram (ECHO).

A mild dilated LA and concentric LVH, with no Regional Wall Motion Abnormality (RWMA). Ejection Fraction (EF) 58% with severe eccentric Mitral Regurgitation (MR), primarily posteriorly directed. Diastolic dysfunction was noted. There was trivial MR, Aortic Regurgitation (AR) and mild Tricuspid Regurgitation (TR) with Pulmonary Artery Systolic Pressure (PASP) of 40 mmHg. Freely mobiling echogenic focci seen in attached to posterior wall of RA above the tricuspid valve measuring as body (20×19 mm) and stalk (5 mm) (indicated by red arrow)

The blood culture showed the presence of K. rosea, a rare pathogen, which is significant in the context of the patient’s condition, and the Antibiotic Susceptibility Test (AST) showed highly sensitive for gentamycin, vancomycin, clindamycin, nitrofurantoin, cefotaxime and amikacin. The antinuclear antibody was negative. Hence, the patient was started on i.v. vancomycin (1 gm) for 3 days, along with supportive treatment that including Inj. pantoprazole (40 mg), Inj. ondansetron (4 mg), tab. paracetamol (650 mg), Tablet (tab.) clonazepam (0.25 mg) and a capsule of bifilac. The following day, a mycotic aneurysm in the right popliteal artery was found after patient complaints of pain, for which, the therapeutic regimen consisted of the administration of i.v. ceftriaxone {2 gm Once Daily (OD) for six weeks} and i.v. vancomycin (500 mg BD for four weeks) through intravenous route was given. Continuous monitoring was done to prevent further attacks of aneurysm.

Finally, the patient was provisionally diagnosed with IE with healed vegetation, vasculitis, microcytic hypochromic anaemia and right hydroureteronephrosis (grade II/III as per Onen hydronephrosis grading system [1]). The patient’s symptoms improved, and she became haemodynamically stable with no fever spikes, so i.v. gentamycin (60 mg TDS for 4-6 weeks) and i.v. ceftriaxone (2 gm OD) continued for four weeks, along with supportive treatment. The patient was advised to consume iron-rich foods to improve anaemia and to promptly visit if they experience bleeding or fever spikes. Then, the patient was reviewed after every three weeks till she patient becomes stable.

Discussion

The current study presented a unique case of IE caused by K. rosea in a non immunocompromised patient. The findings revealed significant clinical challenges, such as persistent fever, cardiac involvement with vegetation on both the mitral and aortic valves, and a rare mycotic aneurysm. Comprehensive diagnostic assessments confirmed K. rosea bacteraemia, which was sensitive to a wide spectrum of antibiotics. The patient showed favourable recovery following a four-week antibiotic regimen of vancomycin, ceftriaxone, and supportive care. These findings underline the diagnostic intricacies of atypical pathogens in IE, particularly in non immunocompromised hosts.

Infective endocarditis is a severe and possibly life-threatening medical illness characterised by inflammation of the endocardial surface of the heart, predominantly affecting the myocardium [2]. In the wider population, it affects 2.6 to 7 per 100,000 people per year, and epidemiological studies indicate that the incidence is escalating [2,3]. Historically, IE has been linked to oral and skin microbiota, particularly those caused by Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species [4]. But the clinical setting of this multifaceted disease is not unidimensional, and microorganisms sometimes surprise clinicians by having blood cultures. Such infections are unexpected, like K. rosea is very rare and exhibit a remarkably low prevalence, as seen by the scarcity of recorded occurrences within the medical literature [5-12].

Nevertheless, the aforesaid case about a 42-year-old female patient underscore the distinctive nature of this complex ailment. Despite being a typically non pathogenic microbe present in the normal human skin flora, K. rosea occurs in patients with immunocompromised condition or co-morbidities [7,9,11,12]. In the present case, however, K. rosea was unexpectedly identified as the aetiological culprit without any predisposing factor such as immunocompromised status. In literature, the authors found only two cases with K. rosea in non immunocompromised patients, emphasising the rare occurrence of K. rosea in non immunocompromised patient which made the case unique. The current case was similar to the case report by Fujimiya T and Sato Y, in which K. rosea occurred in non-compromised patient [8]. Similarly, another case report by Lee MK et al., where the K. rosea in 58-year-old healthy women as descending necrotising mediastinitis [13].

A Gram-positive, coagulase-negative coccus, K. rosea, of the family Micrococcaceae, belongs to the Actinobacteria phylum. It is a part of the normal human skin flora and is generally considered non pathogenic [5]. It is rarely reported and is associated with opportunistic infection in immunocompromised individuals [5-7]. From various literatures till date, only a few cases have presented with K. rosea causing cardiomyopathy morbidity, making it a dramatically uncommon cause in this respect [5-12]. Moreover, based on the genomic sequences, only five genes were separated from the strain, includes NCTC2676, NCTC7514, NCTC7512, NCTC7528 and NCTC7511, which are responsible for the IE inpatient with immunocompromised patients, yet in patients with non immunocompromised the genome sequence were not identified, makes it controversial and rare [14].

The clinical manifestation of the patient encompassed an extended period of pyrexia, cardiac palpitations and dyspnoea, prompting apprehension for her general wellbeing. The comprehensive diagnostic evaluation identified the presence of microcytichypochromic anaemia and vascular abnormalities in the upper limbs. The results prompted subsequent inquiry into the cardiac wellbeing of the patient, ultimately resulting in the detection of IE caused by K. rosea. The case serves as a notorious example of how seemingly unrelated symptoms can coalesce to reveal a complex medical problem, highlighting the importance of thorough clinical assessments. K. rosea, an atypical causative agent of IE, has the potential to cause pathogenic infections in humans with intact immune systems [7]. The microbe in question is commonly regarded as an a typical causative agent of IE [7,9,11,12]. Studies show that Kocuria species infections are frequently found in individuals with compromised immune systems or pre-existing medical disorders [5,6,9-12]. Previous studies have frequently associated K. rosea infections with immunocompromised state as seen in reports by Moreira JS et al., and Gunaseelan P et al., where these studies emphasised the opportunistic nature of the pathogen, often in the context of prior valve abnormalities or device-associated infections [5,6]. In contrast, there is a case reported in Japan involved 79-year-old non immunocompromised patient who presented with complaints of breathlessness and fatiguability, had K. rosea in the blood culture and aortic valve vegetation from ECHO findings [8]. Similarly, our non immunocompromised patient presented with positive K. rosea blood culture and aortic valve vegetation in ECHO, made the present case a unique, with no such case reported in India. Thus, it is important to consider that the presence of bacteraemia induced by K. rosea in blood cultures and possibility that IE could also be caused by this organism, even in patients without weakened immune systems.

Antibiotics’ potential efficacy of antibiotics in treating K. rosea-induced IE is crucial, but there are no established guidelines for this bacterium-related IE [15]. In a case study by Fujimiya T and Sato Y, a four-week regimen of ampicillin-sulbactam was administered [8]. In another case report by Gunaseelan P et al., treated with vancomycin for 14 days and ceftriaxone for four weeks [6]. Also, other studies treated with various antibiotics based on the AST [5,9-12]. Similarly, in the present case patient, the antibiotic regimens including vancomycin, gentamicin and ceftriaxone, were given based on the AST.

This similarity in AST-guided therapy across various studies reinforces the pathogen’s consistent antibiotic susceptibility, emphasising the critical role in individualised treatment plans.

In the present case study, patient’s medical situation was further exacerbated by the emergence of a mycotic aneurysm in the right popliteal artery, for which the therapeutic regimen consisted of the administration of ceftriaxone and vancomycin through intravenous route. Furthermore, there is a lack of clarity on the optimal length of antibiotic treatment for infections caused by this particular bacterium, with a literature suggesting a duration of four weeks [5,6,8]. The Japanese Circulation Society’s 2017 guidelines recommend four to six weeks of treatment for native valve endocarditis but do not include specific recommendations for K. rosea [15]. In the present case, patient demonstrated a good recovery with a course of antibiotic medicines for a period of four weeks. However, considering the possible danger of vegetation embolisation, the authors maintained a diligent monitoring by frequent echocardiograms.

Conclusion(s)

The present case highlights the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges posed by K. rosea-induced IE, particularly in non immunocompromised patients. The present case report emphasises the need for a comprehensive clinical assessment, timely microbiological diagnosis, AST-guided antibiotic therapy, and involving multidisciplinary approach, especially considering the rare occurrence of K. rosea, a potentially fatal microbe as a causal agent in non immunocompromised patients. It underscores the need for heightened awareness among the clinicians regarding atypical pathogens in IE and the development of the standardised treatment protocols.

WBC: White blood cells; RBC: Red blood cells; MCV: Mean corpuscular volume; MCH: Mean corpuscular haemoglobin; MCHC: Mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration; RDW-CV: Red blood cell distribution width; TIBC: Total iron-binding capacity; UIBC: Unsaturated iron binding capacity; A/G: Albumin/globulin; SGOT: Serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase; SGPT: Serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase; AST: Aspartate aminotransferase; ALT: Alanine aminotransferase; ESR: Erythrocyte sedimentation rate; CRP: C-reactive protein; HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; HBsAg: Hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; PA: Postero-anterior; ECHO: Echocardiogram; CT: Computed tomography; USG: Ultrasonography

[1]. Onen A, Grading of hydronephrosis: An ongoing challengeFront Pediatr 2020 8:45810.3389/fped.2020.0045832984198PMC7481370 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Cahill TJ, Baddour LM, Habib G, Hoen B, Salaun E, Pettersson GB, Challenges in infective endocarditisJ Am Coll Cardiol 2017 69(3):325-44.10.1016/j.jacc.2016.10.06628104075 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Vilcant V, Hai O, Bacterial EndocarditisIn: StatPearls [Internet] 2024 Treasure Island (FL)StatPearls Publishing[cited 2024 Feb 9]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470547/ [Google Scholar]

[4]. Rajani R, Klein JL, Infective endocarditis: A contemporary updateClin Med Lond Engl 2020 20(1):31-35.10.7861/clinmed.cme.20.1.131941729PMC6964163 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5]. Moreira JS, Riccetto AG, da Silva MT, Vilela MM, Endocarditis by Kocuria rosea in an immunocompetent childBraz J Infect Dis 2015 19(1):82-84.10.1016/j.bjid.2014.09.00725523077PMC9425231 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Gunaseelan P, Suresh G, Raghavan V, Varadarajan S, Native valve endocarditis caused by Kocuria rosea complicated by peripheral mycotic aneurysm in an elderly hostJ Postgrad Med 2017 63(2):135-37.10.4103/jpgm.JPGM_441_1628397739PMC5414425 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Ziogou A, Giannakodimos I, Giannakodimos A, Baliou S, Ioannou P, Kocuria species infections in humans-A narrative reviewMicroorganisms 2023 11(9):236210.3390/microorganisms1109236237764205PMC10535236 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Fujimiya T, Sato Y, A case of infective endocarditis caused by Kocuria rosea in a non-compromised patientJ Cardiol Cases 2022 27(3):89-92.10.1016/j.jccase.2022.10.01336910031PMC9995668 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Kiraz A, Durmaz S, Baykan A, Perçin D, Endocarditis and Bacteremia due to Kocuria rosea following heart valve replacementEur J Basic Med Sci 2013 3(4):93-95.10.15197/sabad.2.3.18 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[10]. Serefhanoglu K, Oklu E, Kocuria rosea bacteremia: Two case reports and a literature reviewArch Med Sci–Civiliz Dis 2017 2(1):121-24.10.5114/amscd.2017.70601 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[11]. Martins M, Pimentel F, Pinto A, Staring G, Costa W, Infective endocarditis due to Kocuria rosea in a patient with ventricular septal defect: Emerging speciesInt J Med Rev Case Rep 2021 5(2):65-66.10.5455/IJMRCR.Kocuria-rosea-172-1605821917 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[12]. Srinivasa KH, Agrawal N, Agarwal A, Manjunath CN, Dancing vegetations: Kocuria rosea endocarditisCase Rep 2013 2013:bcr201301033910.1136/bcr-2013-01033923814223 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13]. Lee MK, Choi SH, Ryu DW, Descending necrotizing Mediastinitis caused by Kocuria rosea: A case reportBMC Infect Dis 2013 13:47510.1186/1471-2334-13-47524112281PMC3852562 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[14]. Turnbull JD, Russell JE, Fazal MA, Grayson NE, Deheer-Graham A, Oliver K, Whole-genome sequences of five strains of Kocuria Rosea, NCTC2676, NCTC7514, NCTC7512, NCTC7528, and NCTC7511Microbiol Resour Announc 2019 8(44):e00256-19.10.1128/mra.00256-1931672735PMC6953506 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[15]. Nakatani S, Ohara T, Ashihara K, Izumi C, Iwanaga S, Eishi K, JCS 2017 guideline on prevention and treatment of infective endocarditisCirc J Off J Jpn Circ Soc 2019 83(8):1767-809.10.1253/circj.CJ-19-054931281136 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]