Mucinous Carcinoma (MC) of the breast is a rare histological subtype of invasive breast cancer, accounting for approximately 2% of all breast carcinomas. Characterised by abundant extracellular mucin, it predominantly affects postmenopausal women, with a median age of onset around 70 years [1-3]. The current World Health Organisation (WHO) 5th edition categorises MC into PMC (>90% mucin) and MMC (10-90%) [1]. Type A (hypocellular) and type B (hypercellular) subtypes are distinguished based on cellularity, with type B often demonstrating neuroendocrine differentiation [4,5].

Clinically, PMCs are known for their indolent behaviour and favourable prognosis, often associated with luminal A biological profiles that are mainly Oestrogen Receptor (ER) and Progesterone Receptor (PR) positive, with a lack of HER2 expression [6,7]. In contrast, MMCs are more aggressive, exhibiting higher tumour grades, lymphovascular invasion and lymph node metastases, thereby mimicking non mucinous carcinomas [1,8,9]. Despite their clinical significance, limited literature focuses on the comparative analysis of PMC and MMC, particularly in the Indian demographic.

The aim of the present study was to analyse and compare the clinicopathological profiles of both PMC and MMC. This includes evaluating hormone receptor status and biomarker profiles of both subtypes, as well as, assessing treatment modalities and their survival outcomes. The present study seeks to provide insights for tailoring management by highlighting the prognostic differences between these subtypes.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted in the Department of Pathology, Christian Medical College, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India, from January 2017 to December 2021. Study included all histologically confirmed MC cases. PMC and MMC subtypes were identified based on the current WHO classification of breast tumours, 5th edition, 2022 [1].

Inclusion criteria: All patients who had undergone surgical resection with prior core biopsies, along with a few patients who only underwent core biopsy and did not undergo surgery, were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria: All other cases of breast carcinoma, such as ductal carcinoma Not Otherwise Specified (NOS), micropapillary carcinomas, and metaplastic carcinomas, were excluded from the study. Additionally, cases without immunoprofiles and those that underwent lumpectomy elsewhere, with only completion surgeries at our hospital, were also excluded.

Sample size: A total of 2043 breast carcinoma cases were diagnosed from 2017 to 2021, out of which 71 were diagnosed as MC.

Study Procedure

Data were retrieved from the electronic database system of the study Department. Various clinicopathological details, including age, gender, presenting complaints, family history, tumour location, size and number, were analysed. Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) slides of core biopsies and surgical resections were reviewed, along with their hormone receptor status and MIB1 index (wherever available). An average of 12 H&E slides (10-15 slides per case) were reviewed for the resection specimens, which included lymph nodes (both sentinel and axillary node dissection).

The tumours were graded according to the Nottingham histologic score [1] and staged based on the current Tumor, Node and Metastasis (TNM) classification of the 8th American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) edition [10]. The Nottingham modification of the Bloom-Richardson system [1] is based on tumour tubule formation, nuclear pleomorphism and the number of mitotic figures, each of which is assigned a score of 1, 2 or 3. A grade of 1 is assigned when the total score is between 3-5, grade 2 when the points are between 6-7, and grade 3 when the points are between 8-9. Three pathologists reviewed the slides with minimal interobserver variability. Details of various treatment modalities given to the patients, along with their responses to treatment, were recorded. Additional mutational studies, wherever conducted, were also noted.

Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, the Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were performed to compare various characteristic features between patients with PMC and MMC. The two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum (Mann-Whitney) test was used for comparative analysis of age at diagnosis, tumour size, mitotic rate per 10 High-Power Fields (HPF), number of lymph nodes examined, and duration of follow-up. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant and was calculated using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 26.0.

Results

Clinical details with follow-up: Clinical details of all MC cases along with a comparative analysis between PMC and MMC were summarised in [Table/Fig-1]. A total of 2,043 breast carcinoma cases were diagnosed from 2017 to 2021 (5 years), out of which 71 were diagnosed as MC, resulting in a rate of 3.4%. Among these, 58 (82%) cases were diagnosed as PMCs, while 13 (18%) cases were diagnosed as MMCs. Most of the cases were seen in females, with only 2 (2.8%) of all cases occurring in males, resulting in a male-to-female ratio of 1:34.5. The mean age at diagnosis was 57.6 years, with MMC diagnosed at a slightly earlier age (56.7 years compared to 57.8 years in PMC). Four patients were over 80 years of age at the time of diagnosis, and all of them had cases of PMC. A total of 68 (95.7%) cases presented with a breast lump, while 4.2% presented with other complaints such as itching and nipple discharge. Ten (14.7%) cases of MC had a family history of malignancies, including ovarian, endometrial and breast carcinomas. The tumour was located in the right breast in 35 (49.2%) cases and in the left breast in 36 (50.7%) cases. MMCs occurred slightly more in the left breast (53.8%) compared to PMC, which had almost equal occurrences in both the right and left breasts. Most tumours were located in the upper outer quadrant, followed by the central region.

Clinical details for Pure Mucinous Carcinoma (PMC) and Mixed Mucinous Carcinomas (MMC). PMC’s showing slightly earlier age at presentation. The MMC’s having a higher percentage of patients undergoing Modified Radical Mastectomy (MRM) compared to PMC.

| Clinical details | Total cases

n (%) | PMC

n (%) | MMC

n (%) | p-value |

|---|

| Number of cases | 71 (100) | 58 (81.69) | 13 (18.31) | |

| Gender | Males-2 (2.82)

Females-69 (97.18) | Males-2 (3.4)

Females-56 (96.5) | Males-0

Females-13 (100) | 1.000 |

| Age at diagnosis (years, mean±SD) | 57.6±14.96 | 57.84±15.6 | 56.7±12.04 | 0.816 |

| No. of patients above 80 years | 4 (5.6) | 4 (6.8) | 0 | - |

| Family history of malignancies | 10 (14.71) | 8 (11.7) | 2 (15) | 0.939 |

| Presenting complaints | Self detected lump-68 (95.7)

Other symptoms-3 (4.2) | Self detected lump-56 (96.5)

Other symptoms-2 (3.4) | Self detected lump-12 (92.3)

Other symptoms-1 (7.6) | 0.492 |

| Tumour location, right/left breast | Right breast-35 (49.2)

Left breast-36 (50.7) | Right breast-29 (50)

Left breast-29 (50) | Right breast-6 (46.1)

Left breast-7 (53.8) | 0.251

0.411 |

| Median follow-up (months) | 28 | 25 | 38 | 0.267 |

| Number of patients with disease recurrence | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.7) | 0 | - |

| Number of patients died of the disease | None | None | None | - |

| Surgery performed | Total cases, n (%) | Pure mucinous carcinoma, n (%) | Mixed mucinous carcinoma, n (%) | p-value |

| Wide Local Excision (WLE) | 12 (16.9) | 11 (18.9) | 1 (7.69) | 0.183 |

| Simple Mastectomy (SM) | 16 (22.5) | 12 (20.6) | 4 (30.7) |

| Modified Radical Mastectomy (MRM) | 34 (47.8) | 26 (44.8) | 8 (61.5) |

| Only core biopsies | 9 (12.6) | 9 (15.5) | 0 |

The most common surgery performed was Modified Radical Mastectomy (MRM) (47.8%), followed by Simple Mastectomy (SM) (22.5%) and Wide Local Excision (WLE) (16.9%). In both PMC and MMC, MRM was the predominant surgery, followed by SM. All cases of MMCs (100%) underwent surgery. Only 45 (77.5%) cases of PMCs required surgery, although this was not statistically significant (p-value=0.183). A total of 9 (12.6%) PMC cases were diagnosed only on core biopsies, and these patients did not undergo any surgeries at the study hospital.

Follow-up details were available for 61 cases, with a median follow-up duration of 28 months. Only 1 (1.6%) case of PMC had both local and systemic recurrence. No patient had succumbed to the disease till the last day of follow-up.

Pathological details: Pathological details of all MC cases, along with a comparative analysis between PMC and MMC were summarised in [Table/Fig-2]. The mean size of the tumour was 3.3 cm, with a median size of 2.9 cm.

Pathological details for both Pure Mucinous Carcinoma (PMC) and Mixed Mucinous Carcinomas (MMCs). All significant p-values are in bold. MMC’s have a higher histologic score with significant higher rates of lymphovascular invasion, DCIS and lymphnode metastasis.

| Pathological details | Total cases (N=71), n (%) | PMC (n=58), n (%) | MMC (n=13), n (%) | p-value |

|---|

| Tumour size (mm) mean±SD) | 33±1.85 | 34±1.96 | 30±1.25 | 0.687 |

| Tumour number | Single-69 (97.18)

Multiple-2 (2.82) | Single-56 (96.5)

Multiple-2 (3.4) | Single-13 (100)

Multiple-0 | 0.497 |

Tumour subtype,

type A/type B | Type A-49 (71)

Type B-17 (24.64)

Both type A and type B-3 (4.35) | Type A-40 (68.9)

Type B-13 (22.4)

Both type A and type B-3 (5.1) | Type A-9 (69.2)

Type B-4 (30.7)

Both type A and type B-0 | 0.855 |

| Mucinous cut surface on gross examination | 38 (67.86) | 33 (71.74) | 5 (50) | 0.159 |

| Well defined tumour borders | 31 (53.45) | 27 (58.7) | 4 (33.3) | 0.117 |

| Nottingham histologic score |

| Score 1 | 41 (57.75) | 37 (63.79) | 4 (30.7) | 0.017* |

| Score 2 | 29 (40.85) | 21 (36.21) | 8 (61.54) |

| Score 3 | 1 (1.49) | 0 | 1 (7.69) |

| Mitosis/10HPF | Mean- 3.1

Range- 1-9 | Mean- 2.7

Range- 1-9 | Mean- 4.6

Range- 1-8 | 0.004* |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 14 (20.59) | 6 (10.91) | 8 (61.54) | 0.001* |

| Dermal lymphovascular invasion | 2 (3.45) | 0 | 2 (15.38) | 0.007 |

| Perineural invasion | 2 (3) | 1 (1.82) | 1 (7.69) | 0.260 |

| Paget’s disease | 1 (2.0) | 1 (1.7) | 0 | 0.549 |

| Cases with DCIS | 20 (29.85) | 12 (22.2) | 8 (61.5) | 0.014* |

| Patterns of DCIS | Solid-13 (18.3)

Comedo with necrosis-4 (5.6)

Cribriform-6 (8.45) | Solid-7 (26.92)

Comedo with necrosis-1 (1.4)

Cribriform-2 (3.4) | Solid-6 (46)

Comedo with necrosis-3 (5.1)

Cribriform-4 (30.7) | 0.002*

0.002*

0.001* |

| Sentinel node dissection | 10 (18.52) | 7 (16.67) | 3 (25) | 0.748 |

| Axillary node dissection | 43 (79.63) | 34 (58.6) | 9 (69.2) |

| No axillary surgery | 18 (25.3) | 16 (27.5) | 2 (15.3) |

| Number of cases with lymph node metastasis | 10 (14.08) | 5 (9%) | 5 (38) | 0.033* |

| Number of lymph nodes examined, mean (range) | 10.03 (1-32) | 9.6 (1-20) | 11.6 (4-18) | 0.564 |

| Number of metastatic lymph nodes, mean (range) | 0.4 (1-5) | 0.2 (1-3) | 1.2 (1-5) | - |

| Extranodal extension | 2 (2.8) | 0 | 2 (100) | - |

| Positive margin | 2 (3.28) | 2 (4) | 0 | 1.000 |

| TNM stage | Total cases (N=71), n (%) | PMC (n=58), n (%) | MMC (n=13), n (%) | p-value |

| Tumour stage | T0-3 (17.65)

T1-10 (14.0)

T2-39 (54.9)

T3-4 (5.6)

T4-2 (2.8) | T0-3 (7)

T1-9 (15.5)

T2-31 (53.4)

T3-3 (5.1)

T4-2 (3.4) | T0-0

T1-1 (7.6)

T2-8 (61.5)

T3-1 (7.6)

T4-0 | 0.760 |

| Lymph node stage | N0-35 (64.8)

N0 (ITC)-1 (1.8)

N1 (mi)-0

N1a-11 (20.3)

N2a-1 (1.7)

N3a-0 | N0-32 (55.1)

N0 (ITC)-1 (1.7)

N1 (mi)-0

N1a-5 (8.6)

N2a-0

N3a-0 | N0-3 (23)

N0 (ITC)-0

N1 (mi)-0

N1a-6 (46.1)

N2a-1 (7.6)

N3a-0 | 0.002* |

| Distant metastasis | 3 (4.2) | 3 (5.1) | 0 | - |

*DCIS: Ductal carcinoma in-situ; HPF: High-power field; *The p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant

The PMCs had a slightly larger mean size compared to the MMCs (3.4 cm vs 3.0 cm). A total of 97.2% of patients presented with a single tumour, while only 2.8% had multiple tumours. All cases with multiple tumours were PMCs. Regarding the gross appearance of the tumours, PMCs had a higher number of cases with a mucinous cut surface (71.7% vs 50%) and a well-defined tumour border (58.7% vs 33.3%) compared to MMCs. Most of the tumours had a Nottingham histologic score of 1 (57.7%). When compared to PMCs, a Nottingham histologic score of 2 was predominantly seen in MMCs (61.5% vs 36.2%, p-value of 0.017), which was statistically significant.

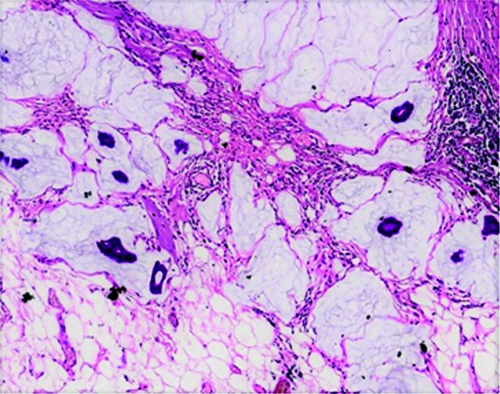

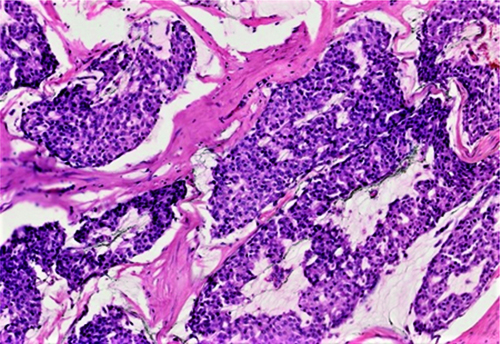

On microscopy, the tumours were further classified into type A (hypocellular) and type B (hypercellular) morphological forms. Among the cases, 49 (71%) cases had type A, 17 (24.6%) cases had type B, and 3 (4.3%) cases exhibited both type A and type B features. Although statistically not significant, type B features were seen more commonly in MMCs compared to PMCs (30.7% vs 22.4%). The type A tumours were hypocellular and arranged in tubules, nests, and sheets, with mild to moderate nuclear pleomorphism, coarse chromatin and moderate to scant amounts of cytoplasm. The tumour cells were noted to be floating in pools of extracellular mucin [Table/Fig-3]. The type B tumours were hypercellular and predominantly arranged in nests, sheets, and cribriform architecture, with mild to moderate nuclear pleomorphism, coarse chromatin, and moderate to scant amounts of cytoplasm. They had scant amounts of extracellular mucin compared to the type A tumours [Table/Fig-4].

Mucinous carcinoma, hypocellular/ type A. The tumour cells are seen floating in abundant extracellular mucin pools (H&E, 100x).

Mucinous carcinoma, hypercellular/type B subtypes. Hypercellular tumour with low to intermediate nuclear grade, floating in lesser amount of mucin pools compared to the pure mucinous carcinomas (H&E, 100x).

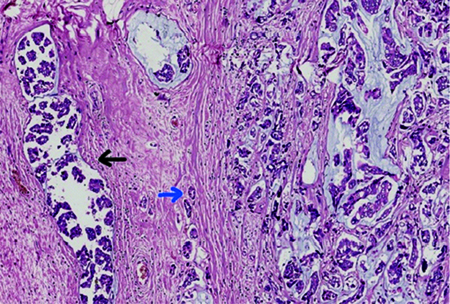

Out of the 13 MMCs, 2 cases had both micropapillary and ductal carcinoma components. One case had both micropapillary and neuroendocrine components, eight cases had only the ductal carcinoma component, and two cases had only the micropapillary carcinoma component. The percentage of various components is detailed in [Table/Fig-5]. The micropapillary components showed clusters of cuboidal to columnar cells without any fibrovascular cores, with clear spaces around the tumour clusters. The ductal carcinoma components demonstrated an infiltrative tumour arranged in trabeculae and nests of cells with mild to moderately pleomorphic nuclei infiltrating the stroma. MMC with both ductal carcinoma and micropapillary carcinoma components has been shown in [Table/Fig-6].

Details of various non mucinous component of mixed mucinous carcinoma.

Type of non mucinous component in mixed

mucinous carcinoma | Number (n) of cases with other

components | Percentage (%) of each

component |

|---|

| Ductal component | 8 | 20%-60% |

| Micropapillary component | 2 | 5% in one case

50% in other case |

| Micropapillary+ductal component | 2 | 5-10% micropapillary and 30-40% ductal |

| Micropapillary+neuroendocrine component | 1 | 20% micropapillary and 5% neuroendocrine |

Mixed mucinous carcinoma with micropapillary carcinoma component (black arrowhead) and ductal carcinoma component (blue arrowhead) (H&E, 100x). The micropapillary components shows clusters of cuboidal to columnar cells without any fibro vascular cores with clear spaces around the tumour clusters. The ductal carcinoma component shows tubules infiltrating the stroma.

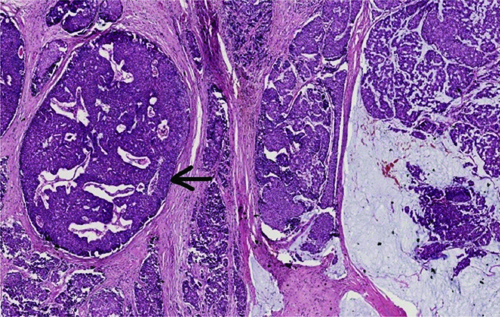

The overall mitotic activity ranged from 1 to 9 mitotic figures per 10 High Power Fields (HPF), with a mean of 3.1/10 HPF. MMCs exhibited significantly higher mean mitotic activity compared to PMCs (4.6 vs 2.7, p-value=0.004). A total of 20.5% of MC cases had lymphovascular invasion, with MMCs exhibiting a much higher percentage than PMCs (61.5% vs 10.9%, p-value=0.001). Additionally, dermal lymphovascular invasion was mainly observed in MMCs compared to PMCs (15.3% vs 0%, p-value=0.007). Only 2 (3%) cases had perineural invasion, one of which was a PMC and the other an MMC. Only 1 (2%) case, which was a PMC, had Paget’s disease of the nipple. Ductal Carcinoma In-situ (DCIS), depicted in [Table/Fig-7], was seen in 29.8% of the total cases, with a higher occurrence in MMCs compared to PMCs (61.5% vs 22.2%, p-value=0.014). All patterns of DCIS, including solid, cribriform and comedo, were seen more commonly in MMC than in PMC, which was statistically significant as shown in [Table/Fig-2]. Only 3.2% of all cases exhibited margin positivity, and all were PMCs.

Mixed mucinous carcinoma with ductal carcinoma in-situ (black arrowhead) (H&E, 40x). The ductal carcinoma in-situ shows solid and cribriform patterns with intermediate nuclear grade.

Regarding axillary surgery, 18.5% of patients underwent sentinel node dissection, with a slightly higher percentage observed in MMCs compared to PMCs (25% vs 16.6%), though this was not statistically significant. A total of 79.6% of cases underwent axillary node dissection, also showing a slightly higher percentage in MMCs compared to PMCs (69.2% vs 58.6%), which was not statistically significant. Lymph node metastasis was noted in 14.08% of cases, with significant lymph node positivity in MMCs compared to PMCs (38% vs 9%, p-value=0.033). Extranodal extension was observed in only 2.8% of cases, all of which were MMCs.

Most of the MCs belonged to tumour stage T2 as per the TNM staging (54.9%), with both PMCs and MMCs showing similar findings. Most patients with lymph node metastasis had a lymph node stage of N1a (20.3%). A higher number of MMCs were found at stages N1a (46.1% vs 8.6%) and N2a (7.6% compared to 0%) compared to PMCs, which was statistically significant (p-value=0.002). A total of 3 (4.2%) cases, all of which were PMCs, had distant metastasis detected on PET scans, which showed metastasis to the liver, bone and lung.

Other treatment modalities [Table/Fig-8]: A total of 19.7% of all cases received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and neoadjuvant hormonal therapy. Additionally, 22.5% of all MCs received adjuvant chemotherapy, with a higher proportion of MMCs compared to PMCs (46.1% vs 23.8%, p-value=0.042). Adjuvant radiotherapy was administered to 28.1% of all cases, with PMCs receiving slightly more than MMCs, although this difference was not statistically significant (29.3% vs 23%). Adjuvant hormonal therapy was given to 88.7% of all cases, with 100% of MMC cases and 86.2% of PMC cases receiving this treatment.

Details of systemic therapy.

Systemic

therapy | Total cases

N=71, n (%) | PMC

n=58, n (%) | MMC

n=13,

n (%) | p-value |

|---|

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 14 (19.7) | 12 (21.82) | 2 (15.38) | 1.000 |

| Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy | 14 (19.7) | 12 (21.82) | 2 (15.38) | 0.714 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 16 (22.5) | 10 (23.8) | 6 (46.1) | 0.042* |

| Adjuvant radiotherapy | 20 (28.1) | 17 (29.3) | 3 (23) | 1.000 |

| Adjuvant hormonal therapy | 63 (88.7) | 50 (86.2) | 13 (100) | 1.000 |

*The p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant

The details of the nine patients who underwent only core biopsies are presented in [Table/Fig-9]. Out of these nine cases, five patients were either lost to follow-up or received treatment at other hospitals. Two patients had other concurrent malignancies (renal cell carcinoma and carcinoma of the cervix) and received hormonal therapy. Two patients had metastatic disease to other organs and were also treated with hormonal therapy.

Details of the nine patients with only available core biopsies.

| Number | Patient’s age (years) | Reason for not performing surgery | Treatment

received |

|---|

| 1 | 81 | Concurrent metastatic renal cell carcinoma | Hormonal therapy |

| 2 | 86 | Concurrent carcinoma cervix, stage IIIB | Hormonal therapy |

| 3 | 56 | Metastatic disease to liver, bone and peritoneum | Hormonal therapy |

| 4 | 76 | Metastasis to lung | Hormonal therapy |

| 5 | 58 | cT2N0, was advised surgery | Lost to follow-up |

| 6 | 67 | cT1N0, was advised surgery | Received treatment elsewhere |

| 7 | 72 | cT1N0, did not come back for further treatment and was lost to follow-up | Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy |

| 8 | 75 | cT2N1, did not come back for further treatment and was lost to follow-up | Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy |

| 9 | 65 | cT2N0, got treated from somewhere else | Mastectomy with adjuvant hormonal therapy |

Biomarker details [Table/Fig-10]: Overall, 60 (85.9%) cases showed the Luminal A phenotype, 10 (12.7%) cases showed the Luminal B phenotype, and 1 (1.4%) case showed a triple-negative phenotype. Of all, 70 (98.5%) cases were ER positive, of which 68 (95.7%) cases were ER rich. A total of 61 (85.9%) cases were PR positive, with 33 (46.4%) cases were classified as PR rich. Overall, MMCs exhibited slightly higher ER and PR positivity compared to PMCs. Only 6 (8.4%) cases were HER2 positive. The MIB1 index was available for only 26 cases; among these, 12 cases had a MIB1 proliferation index of <10%, 9 cases had an index of 10-30%, and five cases had an index of >30%.

Biomarker profile for both pure and mixed mucinous carcinomas.

| Parameters | Total cases

n=71, n (%) | PMC

n=58, n (%) | MMC

n=13, n (%) |

|---|

| ER positive | 70 (98.5) | 57 (98) | 13 (100) |

| ER negative | 1 (1.4) | 1 (2) | 0 |

| PR positive | 61 (85.9) | 48 (82.7) | 13 (100) |

| PR negative | 10 (14) | 10 (17.2) | 0 |

| HER2 positive | 6 (8.4) | 5 (8.6) | 1 (7.6) |

| HER2 negative | 64 (90.1) | 52 (89.6) | 12 (92.3) |

| Triple negative | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.7) | 0 |

| MIB1 index Available in | 26 cases | 20 cases | 6 cases |

| <10% | 12 | 9 | 3 |

| 10-30% | 9 | 7 | 2 |

| >30% | 5 | 4 | 1 |

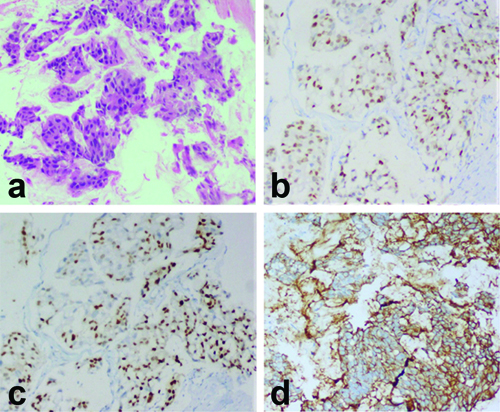

Details of the HER2 positive tumours, along with a comparative analysis between HER2 positive and negative tumours, are provided in [Table/Fig-11]. The rate of occurrence of HER2 positive tumours was 8.4%. Among these tumours, 10.3% were PMCs and 7.6% were MMCs. All HER2 positive tumours were also ER and PR positive. Although none of the values were statistically significant, HER2 positive tumours had a slightly earlier age of presentation (mean age 53.5 years) and a mildly larger mean size (3.9 cm) compared to the HER2 negative group (3.2 cm). Lymphovascular invasion, Paget’s disease, lymph node metastasis and extranodal extension were more commonly observed in HER2 positive tumours. Additionally, 83.3% of the HER2 positive tumours underwent axillary node dissection. A case of HER2 positive MC has been illustrated in [Table/Fig-12a-d]. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapies were the predominant systemic therapies administered, and all HER2 positive cases received adjuvant hormonal therapy.

Clinicopathological details of HER2 positive mucinous carcinomas along with comparative analysis between HER2 positive and negative tumours.

| Number of tumours | HER 2 positive tumours (n=6), n (%) | HER2 negative tumours (n=65), n (%) | p-value |

|---|

| Age at presentation | Mean- 53.5 years

Range- 37-78 years | Mean- 58 years

Range- 35-80 years | 0.868 |

| Presenting complaints | Lump-6 (100%) | Lump-62 (95.3%)

Secondary symptoms-3 (4.6%) | 1.000 |

| Surgery performed | SM-2 (33.3%)

MRM-4 (66.6%)

Core biopsy-0

WLE-0 | Core biopsy-13 (20%)

SM-14 (21.5%)

MRM-28 (43%)

WLE-10 (15.4%) | 0.412 |

| Tumour size | Mean-3.9 cm | Mean-3.2 cm | 0.159 |

| Tumour number | Single-5 (83.3%)

Multiple-1 (16.6%) | Single-63 (96.9%)

Multiple-1 (1.5%) | 0.163 |

| Type of mucinous carcinoma | PMC-5 (83.3%)

MMC-1 (16.6%) | PMC-53 (81.5%)

MMC-12 (18.4%) | 1.000 |

| Tumour subtype | Type A-4 (66.6%)

Type B-2 (33.3%) | Type A-44 (67.6%)

Type B-16 (24.6%)

Both type A+B-3 (4.6%) | 1.000 |

| Nottingham histologic score | Score 1-4 (66.6%)

Score 2-1 (16.6%)

Score 3-1 (16.6%) | Score 1-38 (58.4%)

Score 2-27 (46.5%)

Score 3-0 | 0.088 |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 3 (50%) | 11 (16.9%) | 0.097 |

| Perineural invasion | None | 1 (1.5%) | 1.000 |

| Paget’s disease | 1 (16.6%) | None | 1.100 |

| Ductal carcinoma in-situ | 2 (33.3%) | 18 (27.6%) | 1.000 |

| Sentinel node dissection | 1 (16.6%) | 9 (13.8%) | 1.000 |

| Axillary node dissection | 5 (83.3%) | 38 (58.4%) |

| Number of cases with lymph node metastasis | 2 (33.3%) | 7 (10.7%) | 0.348 |

| Extranodal extension | 1 (16.6%) | 1 (1.5%) | - |

| Tumour stage | T0-0

T1-0

T2-5 (83.3%)

T3-0

T4-1 (16.6%) | T0-3 (4.6%)

T1-10 (15.3%)

T2-34 (85.7%)

T3-4 (6.1%)

T4-1 (1.5%) | 1.000 |

| Lymph node stage | N0-0

N1a-2 (33.3%)

N2a-0

N3a-0 | N0-36 (64.8%)

N1a-9 (20.3%)

N2a-1 (1.7%)

N3a-0 | 0.430 |

| Treatment | NACT-4 (66.6%)

NAHT-0

Adj CT-4 (66.6%)

Adj RT-0

Adj HT-7 (100%) | NACT-10 (57.1%)

NAHT-14 (21.5%)

Adj CT-12 (57.1%)

Adj RT-20 (30.7%)

Adj HT-56 (86.1%) | 1.000 |

SM: Simple mastectomy; MRM: Modified radical mastectomy; WLE: Wide local excision; PMC: Pure mucinous carcinoma; MMC: Mixed mucinous carcinoma; NACT: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy; NAHT: Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy; Adj CT: Adjuvant chemotherapy; Adj RT: Adjuvant radiotherapy; Adj HT: Adjuvant hormonal therapy

a) Mucinous carcinoma (H&E, 100x); b) ER positive tumour cells (H&E, 100x); c) PR positive tumour cells (H&E, 100x); d) HER2 positive tumour cells, score 3+ (H&E, 100x).

Only two patients underwent genetic work-up; one of them was found to have a Breast Cancer gene 2 (BRCA2) mutation.

Discussion

The findings of the present study reaffirm the rarity of MC, with an incidence of 3.4% among breast carcinomas in the present cohort. This is consistent with global estimates of MC prevalence. Notably, while the majority of cases were females a small proportion (2.8%) occurred in males, emphasising the need to consider MC in male breast cancer diagnosis. Literature suggests that less than 1% of MCs are reported in males [11]. These tumours generally have a better prognosis compared to other breast carcinomas [11]. A study by Walsh MM and Bleiweiss IJ suggested that the abundant extracellular mucin pools prevent these tumours from metastasising to lymph nodes, resulting in lesser lymphovascular invasion [12]. MCs are predominantly observed in elderly populations around perimenopausal and postmenopausal age groups [12]. In a study by Budzik MP et al., it was noted that PMCs affected a younger population compared to MMCs [13]. However, another study by Marrazzo E et al., indicated that MMCs occurred in an earlier age group, which is consistent with the present study [14]. It is very important to differentiate between pure and mixed types, as it has been observed that MMCs have a prognosis similar to that of non MC tumours [15,16]. Various literature sources state that the 5-year and 10-year survival rates are 75% and 89%, respectively, while the 5-year and 10-year disease-free survival rates are 95% and 79%, respectively [3,17-19]. The present study’s follow-up data revealed excellent survival outcomes, with only one recurrence and no disease-related deaths. These findings reinforce the generally favourable prognosis of PMCs while underscoring the need for vigilant monitoring of MMCs due to their aggressive features.

Between the type A and type B tumour subtypes, no significant differences were observed in the current study, which is consistent with other studies [20]. Although statistically non significant, PMCs exhibited slightly larger sizes, with well-defined tumour borders and a mucinous cut surface compared to MMCs in the present study. A study by Lannigan AK et al., suggested that PMCs have a slower growth rate, which is why they are often diagnosed when tumours reach a larger size [21]. Some authors proposed that the large volume of mucin may keep the tumour hidden until it reaches a larger size [22].

The authors found that, regarding tumour grade, MMCs had a higher percentage of scores of 2 and 3 compared to PMCs (p-value <0.05). Similar findings were also noted by Budzik MP et al., [13]. According to published data, MMCs have a higher rate of lymphovascular invasion and lymph node metastasis. In the current study, the authors observed that 38% of MMCs had lymph node metastasis (compared to 9% in PMCs, p-value <0.05) and also significant lymphovascular invasion (61.5% compared to 10.9% in PMCs, p-value <0.05), as well as, dermal lymphovascular invasion (15.3% compared to none in PMCs, p-value <0.05) in MMCs [23,24]. Since lymph node metastasis is one of the most critical prognostic factors for breast carcinoma, we can confirm that PMCs have a better prognosis than MMCs, as seen in various previous studies [25-27].

Ductal Carcinoma In-situ (DCIS) with solid, comedo with necrosis, and cribriform patterns were observed more frequently in MMCs in the present study compared to PMCs (p-value <0.05). According to studies by Kryvenko ON et al., DCIS was more common in PMCs compared to mixed types [28]. Extranodal extension has been proven to have a significant association with disease-free survival and local recurrence [29]. Kryvenko ON et al., concluded in their study that 8% of MCs and 7% of MMCs demonstrated extranodal extension, with a higher number of metastatic lymph nodes and distant metastases compared to patients without extranodal extension [28]. In another study by Erhan Y et al., 18% of MMCs and 15% of PMCs had extranodal extension [19]. In the present study, only two cases showed extranodal spread, and both were MMCs. This also supports the conclusion that MMCs have a poorer prognosis than PMCs.

Regarding tumour staging, the authors found that MMCs had slightly higher numbers of T2 and T3 staged tumours compared to PMCs. Capella C et al., observed in their study that tumour size might not be a significant factor in the staging system, as mucin is present in large volumes in these tumours [4]. Most tumours in the present study with lymph node metastasis had a lymph node stage of N1a (20.3%), with significantly higher numbers seen in MMCs compared to PMCs (46.1% vs 8.6%, p-value <0.05). A similar observation of advanced N stage in mixed subtypes was also noted in studies by Esmer AC et al., [30].

Overall, PMCs were associated with a slightly older age at diagnosis compared to MMCs, aligning with existing literature. However, the higher tumour grades and lymphovascular invasion rates observed in MMCs underscore their more aggressive nature. MMCs demonstrated significantly higher rates of DCIS, lymph node metastases, and dermal lymphovascular invasion, reflecting their poorer prognosis.

The overall biological profile predominantly observed in the present study was the luminal A type, accounting for approximately 85.9% of cases, with very few HER2-positive and triple-negative tumours. Marrazzo E et al., observed that 49% of their cases were of the luminal A subtype, while 49% were of the luminal B subtype [14]. Di Saverio S et al., found 81.5% with the luminal A phenotype and 17.1% with the luminal B phenotype [3]. The present study findings were also similar to those in the studies mentioned above. HER2 positivity in MCs is rare and indicates an unfavourable prognosis [3]. The rate of HER2 overexpression in MCs is approximately 5.8% to 9.5% [30]. Studies have shown that these tumours tend to present at an earlier age, as well as having a higher tumour grade, a higher frequency of lymph node metastasis, and overall poorer survival rates [31].

The predominance of the luminal A subtype (85.9%) among MCs correlates with favourable outcomes. However, HER2-positive tumours (8.4%) were more aggressive, exhibiting earlier onset, larger tumour sizes and higher rates of lymphovascular invasion and metastasis.

When the authors compared the present study findings with existing studies, the results aligned well with those from the works of Budzik MP et al., and Marrazzo E et al., which emphasise the prognostic divergence between PMC and MMC [13,14]. The higher incidence of DCIS and lymphovascular invasion in MMCs, observed in the present study, also parallels global data, reaffirming the aggressive behaviour of this subtype. Additionally, the predominance of luminal A profiles in our cohort corroborates existing evidence of favourable biological characteristics in MC. The findings from the current study in comparison with the literature has been presented in [Table/Fig-13] [3,6,13,14,19,22,30].

Findings of the present study compared with the findings in the literature [3,6,13,14,19,22,30].

| Parameters | Di Saverio S et al., [3] (2008) | Budzik MP et al., [13] (2021) | Marrazzo E et al., [14] (2020) | Erhan Y et al., [19] (2009) | Fentiman I et al., [22] (1997) | Esmer AC et al., [30] (2023) | Barkley CR et al., [6] (2008) | Present study |

|---|

| Incidence of MC | 2% | 3.09% | Not available | Not available | Not available | 2.16% | Not available | 3.4% |

| Incidence in males | None | None | none | None | None | None | None | 2.8% |

| Prognosis | Less aggressive compared to ductal carcinomas | Better long term prognosis | Overall good prognosis | Good prognosis with no local recurrence. | Good prognosis with no local recurrence | PMC with better prognosis than MMC | Favourable prognosis with no deaths | Over all good prognosis |

| Age group affected | Median-71 years | 65.5 years | 64.4 years with PMC affecting patients at an earlier age than MMC | 60.1 years | Mean-62 years | Perimenopausal and postmenopausal | Median-56 years | Postmenopausal with a median age-70 years |

| PMC v/s MMC- Prognosis | PMC with good prognosis | MMC with poorer prognosis | MMC prognosis worse than PMC and similar to non mucinous carcinoma | PMC with better prognosis | PMC with better prognosis | PMC with better prognosis | Low rates of local and distant recurrence with no deaths in both PMC and MMC | PMC with better prognosis than MMC |

| Survival rates (5 years/10 years) | 82%/72% | Overall 5 years survival of MC- 95.8%.

Disease free 5 years survival-91.6%. PMC with 100% overall survival (5 years)

MMC with 88.9% overall survival (5 years) | 5 year overall survival-92.1% | One death in each PMC and MMC | PMC-87% (10 year survival)

MMC-54% (10 year survival | MMC with worse survival than PMC | The patents were followed-up for 63 months with no breast cancer related deaths | All patients alive; one recurrence observed |

| Tumour size in PMC | Median size of 15.7 mm | Larger than MMC | Smaller than MMC | Smaller than MMC | Smaller than MMC | Larger than MMC | Mean size of 1.6 cm in all MC | Larger size in PMC with defined borders |

| Lymph node metastasis in MMC | 12% with lymph node metastasis | Higher in MMC compared to PMC | Higher in MMC | Lesser in MMC | Higher in MMC than PMC | Higher in MMC | 13% in all MC | 38% |

| Treatment modalities | Predominantly BCS | Predominantly BCS | Predominantly BCS||followed by radiotherapy and endocrine therapy | Predominantly mastectomy | Predominantly MRM | BCS followed by mastectomy | Predominantly BCS followed by radio therapy and endocrine therapy | MRM most common; 16.9% only underwent BCS |

MC: Mucinous carcinoma; PMC: Pure mucinous carcinoma; MMC: Mixed mucinous carcinoma; MRM: Modified radical mastectomy; BCS: Breast conservation surgery

Regarding various treatment modalities, literature suggests that axillary staging, along with breast- Breast Conserving Surgery (BCS), followed by adjuvant radiotherapy and endocrine therapy, is the most common mode of treatment. Barkley CR et al., and Marrazzo E et al., in their studies, found BCS to be the most commonly performed surgery, followed by mastectomy [6,14]. In the current study, MRM was the most common surgical technique, accounting for 44.8% of all cases, particularly in MMC at 61.5%, reflecting a tendency toward aggressive surgical management for this subtype. Only 16.9% of all cases underwent breast-conserving surgeries in the current study. Despite the global trend favouring BCS, its lower adoption in this cohort highlights the impact of patient preferences and healthcare accessibility. Some patients request mastectomy due to various reasons, including lack of awareness, fear of recurrence, additional expenses, and the requirements of radiation and follow-up.

Most literature shows a lymph node metastasis rate of 12-14%, which is similar to the present study findings of 14.08% nodal metastasis. Diab SG et al., found that lymph node metastasis is associated with a higher chance of recurrence [7]. Giuliano AE et al., stated that although PMCs have a lesser risk for lymph node metastasis, axillary status should be assessed by sentinel lymph node biopsy, as it has minimal morbidity [32]. Therefore, nodal status should be examined carefully. Overall, 39.4% of the tumours underwent neoadjuvant therapies. Marrazzo E et al., reported that only 6.4% of their patients received neoadjuvant treatments in their study [14]. Achicanoy Puchana DM et al., inferred from their study that adjuvant chemotherapy was more frequently administered in MMCs, which aligns with the present study findings (46.1% vs 23.8%, p-value <0.05) [33]. Similar findings were observed in the study by Marrazzo E et al., [14].

Achicanoy Puchana DM et al., also noted that adjuvant radiotherapy did not show any difference in overall survival among patients. Adjuvant hormonal therapy was administered to most of the present study cases, with 86.2% of PMCs and 100% of MMCs receiving it, which is consistent with the study by Marrazzo E et al., Additionally, 18.3% of the present study cases received only endocrine therapy and did not require any surgeries [14]. Barkley CR et al., also reported that 54% of cases received only hormonal therapy [6]. Denduluri N et al., suggested that neo-adjuvant and adjuvant hormonal therapy depend on the characteristics of the tumour and are focused on locally advanced tumours [34].

The distinct differences in prognosis and treatment responses between PMC and MMC underscore the importance of accurate histopathological diagnosis. Routine axillary staging, including sentinel lymph node biopsy, is essential even in PMCs due to the possibility of metastatic spread. Furthermore, although rare, the presence of HER2 positivity warrants consideration for targeted therapy to optimise outcomes.

Limitation(s)

The limited number of MMCs and the minimal number of HER2-positive cases may have affected the results. Since this is a retrospective study, a selection bias cannot be entirely excluded.

Conclusion(s)

Mixed Carcinomas (MCs) of the breast are rare but clinically significant entities with distinct prognostic and therapeutic implications. This study highlights the critical differences between PMC and MMC, emphasising the need for their differentiation in routine clinical practice. While PMCs demonstrate excellent survival outcomes, MMCs require more aggressive management due to their higher tumour grade, lymphovascular invasion, and nodal involvement. Future studies with larger cohorts and longer follow-ups are essential to elucidate these differences further and refine treatment strategies. By tailoring treatment approaches to the specific subtype, clinicians can optimise outcomes and improve the quality of life for patients with MCs.

*DCIS: Ductal carcinoma in-situ; HPF: High-power field; *The p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant

*The p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant

SM: Simple mastectomy; MRM: Modified radical mastectomy; WLE: Wide local excision; PMC: Pure mucinous carcinoma; MMC: Mixed mucinous carcinoma; NACT: Neoadjuvant chemotherapy; NAHT: Neoadjuvant hormonal therapy; Adj CT: Adjuvant chemotherapy; Adj RT: Adjuvant radiotherapy; Adj HT: Adjuvant hormonal therapy

MC: Mucinous carcinoma; PMC: Pure mucinous carcinoma; MMC: Mixed mucinous carcinoma; MRM: Modified radical mastectomy; BCS: Breast conservation surgery