A Prospective Observational Study on Viral Conjunctivitis: An Exasperating Entity

Rupali Tyagi1, Priyanka Gupta2, Aeshvarya Dhawan3

1 Associate Professor, Department of Ophthalmology, Graphic ERA Institute of Medical Sciences, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India.

2 Associate Professor, Department of Ophthalmology, Shri Guru Ram Rai Institute of Medical and Health Sciences, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India.

3 Senior Consultant, Department of Ophthalmology, ASG Eye Hospitals, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Dr. Aeshvarya Dhawan, Senior Consultant, Department of Ophthalmology, ASG Eye Hospitals, Dehradun-248001, Uttarakhand, India.

E-mail: aeshvarya.dhawan@gmail.com

Introduction

The community outburst and rising numbers of viral conjunctivitis cases every year indicate a lack of social awareness, as well as inappropriate diagnosing and treatment modalities.

Aim

To analyse the clinical profile of viral conjunctivitis patients attending the Ophthalmic Outpatient Department (OPD) of a tertiary care hospital to appraise clinical practice guidelines.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective observational study conducted in a tertiary care hospital in the Department of Ophthalmology, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India over a period of three months, from June 1, 2023, to August 31, 2023. A total of 586 patients (time-bound study) were diagnosed with viral conjunctivitis who visited the eye OPD and were enrolled after providing informed consent. Following inclusion, the patients underwent a detailed history and ocular examination. The demographic and clinical profiles were tabulated and analysed. The treatment of referred/already treated cases was also analysed. Categorical variables were presented in numbers and percentages (%). The data were entered into an MS Excel spreadsheet, and analysis was conducted using Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26.0 software.

Results

A total of 586 cases of viral conjunctivitis were reported. Out of these, 263 were newly diagnosed, while 323 cases were already under treatment. The maximum number of cases were between 10 and 20 years of age, with 172 (29.35%) patients. Gender-wise distribution of cases shows that there were 341 (58.19%) males and 245 (41.81%) females. Pain, redness, and watering were the unanimous presenting symptoms. The most common signs were follicles and conjunctival congestion in all 586 (100%) cases, followed by lid swelling. Out of 323 (55.11%) cases already under treatment from elsewhere, 16 (4.95%) cases had been treated by general practitioners. Of these 323 cases, the majority were prescribed a combination of topical antibiotic drops, topical steroids, and topical artificial tear drops in 148 (45.82%) cases, followed by a combination of topical antibiotic drops and topical steroid drops in 65 (20.12%) cases.

Conclusion

The essential finding in the current study was that close to 46% of the cases were using a cocktail of medications that included topical steroids. Moreover, 4.95% of cases had been treated by general practitioners. Proper guidelines for diagnosis and treatment are urgently needed. Policy formulation by regulatory health authorities is required. The significance of raising awareness among the general public and school authorities/staff should not be overlooked.

Awareness, Community outbreak, Pink eye, Recalcitrant viral conjunctivitis

Introduction

Viral conjunctivitis, commonly known as “pink eye,” is one of the most prevalent causes of infectious conjunctivitis in ophthalmic practice, comprising nearly 75% of recalcitrant cases. This high incidence prompts general ophthalmologists to reconsider existing protocols and available treatment options [1]. The infection commonly occurs following direct contact with the virus, airborne transmission, or from reservoirs such as swimming pools, fomites, and close-contact situations. The initial 10 to 14 days are crucial, as this period is highly contagious for the transmission of the virus [2]. The risk of transmission is heightened because adenovirus can remain infectious on environmental surfaces for an extended period. O’Brien TP et al., reported that it can remain infectious on surfaces for up to 4 to 5 weeks [3]. Additionally, adenovirus is stable in the presence of many physical and chemical agents, as well as under adverse pH conditions [4]. For example, adenovirus is resistant to lipid solvents because it lacks lipids within its structure [5]. Furthermore, adenovirus may remain infectious even after freezing [6].

The primary viral agent responsible for conjunctivitis is adenovirus, which accounts for 65-90% of viral conjunctivitis cases, while herpes simplex virus contributes to 1.3-4.8% of acute conjunctivitis cases. Other viruses that can cause conjunctivitis include the varicella (herpes) zoster virus and Molluscum contagiosum. Human adenoviruses can lead to various illnesses, including respiratory and gastrointestinal infections. Subgroups B and D of human adenoviruses are associated with ocular infections, including epidemic keratoconjunctivitis, Acute Haemorrhagic Conjunctivitis (AHC), and pharyngoconjunctival fever [7]. Worldwide, various outbreaks of keratoconjunctivitis associated with human adenoviruses have been reported, with Type 8 being primarily responsible. A study from India has reported the presence of Types 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, and 37 [8].

Coxsackievirus A-24 variant and enterovirus-70 are the two major causative agents of AHC. The spread of AHC is most likely to occur after a flood, according to previous research. Zhang found that there was a distinct seasonal pattern with a peak occurring from August to October and a median onset age of 24 years. AHC is an extremely contagious form of conjunctivitis, and its incubation period is approximately one day. The sequential onset of conjunctivitis in both eyes may occur shortly after contact with an infectious source. In cases of sudden onset follicular conjunctivitis that test negative on an adenovirus detection kit, one should consider the possibility of AHC [6].

As a tertiary and referral Institute, a significant number of patients were observed with viral conjunctivitis who were improperly diagnosed and treated. This situation adds considerable mental stress and financial burden on the patients as well. The present center serves most regions of the Himalayan belt and thus reflects the disease profile in this area of North India. No previous study has been conducted on the profiling of viral conjunctivitis in this region, despite it being one of the most common ophthalmic diseases. Therefore, present study was undertaken to examine the clinical profile of viral conjunctivitis patients attending the OPD and to assess the existing treatment patterns and practices.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective observational study conducted in a tertiary care hospital in Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India over a period of three months, from June 1, 2023, to August 31, 2023. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee with IEC number SGRR/IEC/46/28. The study adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Inclusion and Exclusion criteria: The inclusion criteria were patients diagnosed with viral conjunctivitis, while the exclusion criteria involved patients with any other cause of conjunctivitis or corneal ulcers.

Study Procedure

A total of 586 patients were diagnosed with viral conjunctivitis after visiting the eye OPD and were enrolled after providing their informed consent. Following inclusion, the patients underwent a detailed history and ocular examination. The demographic and clinical profiles were tabulated and analysed. The treatment of referred or already treated cases was also analysed.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages (%). The data were entered into an MS Excel spreadsheet, and the analysis was conducted using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) 26.0 software.

Results

A total of 586 cases of viral conjunctivitis were encountered over a period of three months. Out of these, 263 were newly diagnosed, while 323 cases were already under treatment from elsewhere. Among the 323 cases already under treatment, 16 were treated by general practitioners. The maximum number of cases occurred in the 10-20 years age group, with 172 (29.35%) cases, followed by the 20 years age group, which had 126 (21.50%) cases [Table/Fig-1]. The present study included 341 (58.19%) males and 245 (41.81%) females.

Age-wise distribution of patients of viral conjunctivitis.

| Age (years) | n (%) |

|---|

| <10 | 69 (10.75) |

| >10-20 | 172 (29.35) |

| 20-30 | 126 (21.50) |

| 30-40 | 67 (3.92) |

| 40-50 | 114 (19.45) |

| >50 | 38 (2.22) |

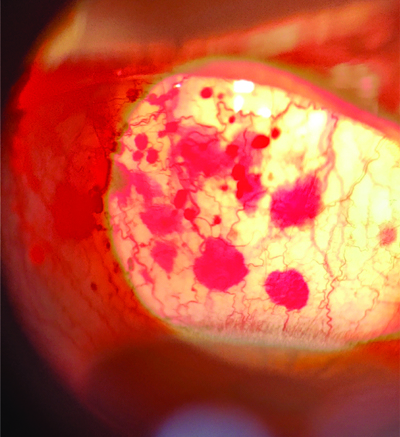

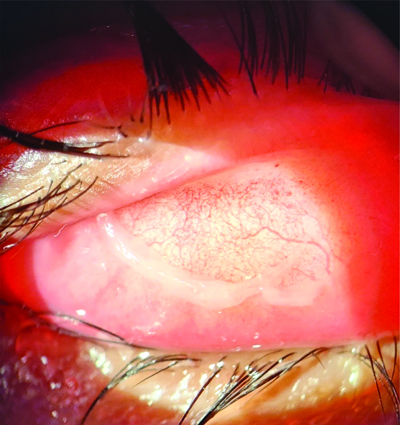

Pain, redness, and watering were presenting symptoms in 100% of the cases. Diminution of vision was reported by 68 (11.60%) cases out of the total 586 cases [Table/Fig-2]. Follicles and conjunctival congestion were uniform clinical signs present in all cases (100%). Lid swelling was the second most common sign, observed in 373 (63.65%) cases, while the least common sign was subepithelial infiltrates, which were seen in 7 (1.19%) [Table/Fig-3]. Clinical images showing petechial haemorrhages and pseudomembranes are shown in [Table/Fig-4,5].

Frequency distribution of symptoms in patients of viral conjunctivitis.

| Symptoms | n (%) |

|---|

| Pain | 586 (100) |

| Redness | 586 (100) |

| Watering | 586 (100) |

| Discharge (purulent) | 117 (19.96) |

| Diminution of vision | 68 (11.60) |

Frequency distribution of signs in patients of viral conjunctivitis.

| Signs | n (%) |

|---|

| Follicles | 586 (100) |

| Conjunctival congestion | 586 (100) |

| Lid swelling | 373 (63.65) |

| Purulent discharge | 122 (20.81) |

| Superficial punctate keratitis | 53 (9.04) |

| Preauricular lymph node enlargement | 23 (3.92) |

| Sub-epithelial infiltrates | 7 (1.19) |

Clinical image showing petechial haemorrhages in case of epidemic viral conjunctivitis.

Clinical image showing pseudomembrane in case of viral conjunctivitis.

An analysis of the treatment for the 323 referred or already treated cases showed that the majority of patients, 148 (45.82%), were treated with a combination of topical antibiotic drops, topical steroids, and topical artificial tear drops, followed by 65 (20.12%) cases treated with a combination of topical antibiotic drops and topical steroid drops. Only eight patients (2.47%) were using only artificial tear drops out of the total 323 referred cases [Table/Fig-6].

Treatment of referred/already treated cases (Elsewhere).

| Eye drops | n (%) |

|---|

| Artificial tear drops only | 8 (2.47) |

| Topical antibiotics only | 32 (9.9) |

| Topical steroids drop only | 55 (17.02) |

| Topical artificial tear drops and topical steroid drops | 15 (4.64) |

| Topical antibiotic drops and topical steroid drops | 65 (20.12) |

| Topical antibiotic drops, topical steroid drop, topical artificial tear drops | 148 (45.82) |

Discussion

The current study involved 586 cases of viral conjunctivitis over a period of three months, of which 263 were newly diagnosed and 323 cases were already under treatment from elsewhere.

In the year 2023, there were numerous reports about an outbreak of acute conjunctivitis. It has different names in India, such as Madras Eye and Joy Bangla [9,10]. The sudden rise in the number of cases is certainly attributed to changes in weather conditions. The damp and increasingly humid environment during the monsoon provides an ideal breeding ground for microorganisms to multiply and spread the infection rapidly. Areas with high population density, such as relief camps, suburban areas, and housing societies, are at a significantly greater risk for the quick transmission of infections [11,12].

The data in the present study were compiled to examine the demographic and clinical trends at the beginning of this recurrent clinical entity. The study highlighted that the disease primarily affected children under 20 years of age. The reason for this occurrence could be attributed to a poor understanding of hygiene among school children. Therefore, raising awareness at the school level is of utmost importance to educate them about hygiene and the isolation of infected students. A lower threshold for absenteeism and increased provisions for medical leave through proper medical documentation should be encouraged. Another affected age group was the working population between 21 and 30 years. The male and female distribution was 58.19% and 41.81%, respectively.

All the patients presented with typical features of pain, redness, and watering. The results were in concordance with another study by Madurapandian Y et al., as seen in [Table/Fig-7] [13]. The lack of a correct diagnosis and the initiation of erratic medications is one of the largest issues; if revisited and corrected, this could lead to a decrease in recalcitrant cases of conjunctivitis. Most patients exhibited typical clinical signs of viral conjunctivitis. The clinical signs have been compared to the study by Pinto RD et al., in [Table/Fig-8] [14]. Differentiating between follicles (viral, bacterial, or toxic) and papillae (allergic), as well as the type of discharge, will certainly aid in achieving a correct diagnosis in most cases of conjunctivitis. A history of any upper respiratory tract infection or a tender preauricular lymph node [2] will further support the diagnosis of viral conjunctivitis. The presence of multiple haemorrhagic spots on the conjunctiva will help establish a diagnosis of epidemic conjunctivitis [15]. Furthermore, the presence of vesicles and corneal involvement should prompt consideration of a herpetic lineage. Thus, these sequelae should be kept in mind while managing such cases.

Comparison of symptoms among patients [13].

| Symptoms | Madurapandian Y et al., [13] | Present study |

|---|

| Redness | 100% | 100% |

| Watering | 100% | 100% |

| Pain | 72% | 100% |

| Discharge | 31% | 19.96% |

Comparison of clinical signs among patients [14].

| Clinical signs | Pinto RD et al., [14] | Present study |

|---|

| Follicles | 95.8% | 100% |

| Pre-auricular lymph node enlargement | 15.3% | 3.92% |

| Subepithelial infiltrates | 13.9% | 1.19% |

Out of the 323 cases who were already being treated elsewhere, 45% were on a combination of eye drops, including antibiotics, steroids, and lubricating agents. This is not in accordance with the treatment guidelines. Such erratic treatments have been highlighted in the literature [16]. Counselling patients and demonstrating patience by the treating ophthalmologist are crucial roles in this scenario. Topical artificial tear drops can be used with varying frequency. From a broader perspective, it is established that topical steroids can cause prolonged viral shedding and increase the duration of conjunctivitis [15]. Unfortunately, due to the easy availability of topical steroids, the prevalence of self-medication in society, and the non judicious use of steroids, various complications arise, leading to an increase in refractory cases of viral conjunctivitis. Therefore, proper awareness campaigns can help patients better manage their condition and reduce the rate of recurrences. The 16 cases treated by practitioners other than ophthalmologists should also be considered, and awareness campaigns or sensitisation policies should include a broader segment of the medical fraternity.

Limitation(s)

The present study had a small sample size and a short duration. The main limitations of the study include a small cohort, being a single-centre study, and a lack of follow-up with the patients.

Conclusion(s)

To conclude, present study found that 4.95% of cases were treated by general practitioners, and 46% of the cases involved the use of a combination of medications, including topical steroids. Although viral conjunctivitis is a very common ophthalmic condition, the irrational and non specific use of medications leads to prolonged duration of the disease, increases the risk of corneal involvement, and ultimately affects visual acuity. This situation contributes to an increased mental, social, and economic burden on society. Proper sensitisation of practitioners and the public is urgently needed. Patients diagnosed with conjunctivitis of presumed adenoviral etiology must undergo further investigation to identify the type of viral strain, and this information should be communicated to a government nodal agency to help identify the types and patterns of outbreaks in the population.

Author Declaration:

Financial or Other Competing Interests: None

Was Ethics Committee Approval obtained for this study? Yes

Was informed consent obtained from the subjects involved in the study? Yes

For any images presented appropriate consent has been obtained from the subjects. Yes

Plagiarism Checking Methods: [Jain H et al.]

Plagiarism X-checker: Oct 19, 2024

Manual Googling: Feb 06, 2025

iThenticate Software: Feb 08, 2025 (16%)

[1]. Keen M, Thompson M, Treatment of acute conjunctivitis in the United States and evidence of antibiotic overuse: Isolated issue or a systematic problem?Ophthalmology 2017 124(8):1096-98.10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.05.02928734327 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Solano D, Fu L, Czyz CN, Viral ConjunctivitisIn: StatPearls [Internet] 2024 Jan Treasure Island (FL)StatPearls PublishingAvailable from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470271/# [Google Scholar]

[3]. O’Brien TP, Jeng BH, McDonald M, Raizman MB, Acute conjunctivitis: Truth and misconceptionsCurr Med Res Opin 2009 25(8):1953-61.10.1185/0300799090303826919552618 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Mena KD, Gerba CP, Waterborne adenovirusRev Environ Contam Toxicol 2009 198:133-67. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Liu C, Adenoviruses. In Belshe RB Ed., 2nd ed.Textbook of human virology 1991 St. Louis, MO, USAMosby Yearbook:791-803. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Muto T, Imaizumi S, Kamoi K, Viral conjunctivitis. Viruses 2023 15(3):67610.3390/v1503067636992385PMC10057170 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Mohanty L, Minj A, Swain J, Panigrahi PK, Ahuja S, Clinical presentations in presumed epidemic viral conjunctivitis: An observational study from a tertiary centre in Eastern IndiaTNOA J Ophthalmic Sci Res 2023 61:445-49.10.4103/tjosr.tjosr_101_23 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[8]. Singh MP, Ram J, Kumar A, Rungta T, Gupta A, Khurana J, Molecular epidemiology of circulating human adenovirus types in acute conjunctivitis cases in Chandigarh, North IndiaIndian J Med Microbiol 2018 36:113-15.10.4103/ijmm.IJMM_17_25829735838 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Mohanasundaram AS, Gurnani B, Kaur K, Manikkam R, Madras eye outbreak in India: Why should we foster a better understanding of acute conjunctivitis?Indian J Ophthalmol 2023 71:2298-99.10.4103/IJO.IJO_3317_2237202982PMC10391441 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Banerjee S, Nath A, Kumar H, Soni NP, Prakash J, Mehta R, Tackling the unprecedented rise in cases of conjunctivitis in Kolkata and Delhi, IndiaNew Microbes New Infect 2023 54:10117110.1016/j.nmni.2023.10117137692290PMC10483042 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. Janani MK, Malathi J, Madhavan HN, Spectrum of adenoviral serotypes of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (“madras eye”) in Chennai population in the past two decades (1991–2014)Sci J Med Vis Res Foun 2016 34:29-62. [Google Scholar]

[12]. Gonzalez G, Yawata N, Aoki K, Kitaichi N, Challenges in management of epidemic keratoconjunctivitis with emerging recombinant human adenovirusesJ Clin Virol 2019 112:01-09.10.1016/j.jcv.2019.01.00430654207 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13]. Madurapandian Y, Rubeshkumar P, Raju M, Janane A, Ganeshkumar P, Selvavinayagam TS, Case report: An outbreak of viral conjunctivitis among the students and staff of visually impoaired school, Tamil Nadu (2020)Front Public Health 2022 10:97820010.3389/fpubh.2022.97820035991078PMC9388931 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[14]. Pinto RD, Lira RP, Arieta CE, Castro RS, Bonon SH, The prevalence of adenoviral conjunctivitis at the Clinical Hospital of the State University of Campinas, BrazilClinics 2015 70(11):748-70.10.6061/clinics/2015(11)0626602522 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[15]. Bialasiewicz A, Adenoviral keratoconjunctivitisSultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2007 7(1):15-23.10.18295/2075-0528.263621654940PMC3086413 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[16]. Chan VF, Yong AC, Azuara-Blanco A, Gordon I, Safi S, Lingham G, A systematic review of clinical practice guidelines for infectious and non-infectious conjunctivitisOphthalmic Epidemiology 2022 29:473-82.10.1080/09286586.2021.197126234459321 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]