Introduction

Cerebral Palsy (CP) is a collection of long-term conditions that impact posture and movement, frequently accompanied by cognitive, sensory, behavioural and communication abnormalities. Children with CP experience a variety of effects on their Quality of Life (QOL), including social, emotional and physical aspects. The CP-specific questionnaire, known as the CP QOL-Child, has not yet been translated or validated in the Kannada language, limiting its applicability in regions where Kannada is the primary language.

Aim

To translate and validate the CP QOL-Child Primary Caregiver questionnaire into Kannada.

Materials and Methods

This was a cross-sectional cultural study conducted at Department of Paediatric Physiotherapy, KLE College of Physiotherapy, Hubballi, Karnataka, India, over the course of one month (September 14, 2024, to October 14, 2024). It included 50 children with CP (ages 4-12) and their primary caregivers. The Child Primary Caregivers were given a Kannada-translated questionnaire and the data were collected. The internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) levels and CP QOL were evaluated and compared. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to evaluate the internal consistency of CP QOL scores; a value of >0.7 was considered indicative of internal consistency and response validity.

Results

The mean age observed was 8.1±2.3 years, with 36 (72%) of the children being diagnosed with spastic quadriplegia. Cronbach’s alpha scores for the items in each quality-of-life area demonstrated very good reliability, ranging from 0.687 to 0.882. Overall, the QOL was found to be 41.8±4.2. QOL significantly decreased as GMFCS levels increased, particularly at levels IV (42.8±1.5) and V (36.8±1.4). Pain and the impact of disability showed no significant differences across the GMFCS levels.

Conclusion

The present study concludes that the Kannada-translated CP QOL-Child Primary Caregiver questionnaire (for ages 4-12) is a reliable tool for assessing parent-reported CP QOL in Kannada-speaking primary caregivers.

Cognitive, Communication abnormalities, Disability, Pain

Introduction

The term “Cerebral Palsy” (CP) refers to a collection of long-term mobility and posture disorders that limit one’s activities and are caused by permanent abnormalities in the developing foetal or infant brain [1]. As a syndrome, CP is characterised by a broad spectrum of symptoms, which can include motor disorders, sensory, cognitive, communication, percepdfetual and behavioural abnormalities; seizure disorders might also be present. The variability in symptoms and their severity among individuals makes CP a complex syndrome rather than a singular disorder [2]. The prevalence of CP varies between 1.5 and 4 per 1,000 live births globally [1,3]. In India, there are 2.95 cases of CP for every 1,000 children surveyed [4]. This high prevalence is partly due to the country’s substantial birth rate and limited access to adequate healthcare services. In countries with middle and lower incomes, such as India, quadriplegia is the most prevalent type [5].

The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines QoL as “an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live and about their goals, expectations, standards and concerns” [6]. The impact of CP on QoL is profound and encompasses multiple domains, including physical, psychological, social and functional well-being [6]. These deficits often result in limitations in daily activities, social isolation and potential mental health challenges. Additionally, these challenges may reduce participation in community and recreational activities, further affecting QoL [6,7]. Assessing QoL can yield meaningful indicators of intervention outcomes, helping to evaluate the effects of clinical treatments on QoL and health services. It also enhances the understanding of disease burden and assists in identifying priority areas for health resource allocation, the development of public health infrastructure and policy recommendations [8].

A thorough framework for comprehending and characterising the effects of CP on individuals is offered by the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), which also takes into account how personal and environmental factors affect function and disability [9]. Environmental elements encompass the social, physical and mental surroundings, such as access to healthcare services, educational support, adaptive equipment and social attitudes toward disability [10].

For children with CP, particularly those between 4 and 12 years of age, several specific challenges arise as they grow and develop. Assessing the QoL in these children involves using standardised questionnaires and assessment tools that cover various dimensions of health and well-being. Commonly used QoL assessment tools include the CP QOL-Child, Paediatric Quality-of-Life inventory 4.0 (PedsQL), KIDSCREEN and Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ), of which the CP QOL-Child is a CP-specific assessment tool that consists of two versions: one for the child self-report and one for the primary caregivers. Its purpose is to evaluate well-being rather than illness [11]. Parent-substituted reporting is especially helpful when children are unable to self-report, as it offers a thorough understanding of the child’s everyday activities and overall QoL [12]. It recognises the significance of gathering the opinions of primary caregivers of children with CP. Primary caregivers are considered to be those who spend at least 18 hours per day with the child.

The translation and validation of the CP QOL Child-Primary Caregiver questionnaire have been confirmed in multiple countries and various languages; however, it has neither been translated into Kannada nor has its efficacy been evaluated. This gap highlights the need for a culturally appropriate adaptation of the CP QOL-Child to ensure that caregivers in Kannada-speaking communities can effectively communicate and assess their child’s QOL.

Materials and Methods

This cross-sectional cultural study was conducted at the Department of Paediatric Physiotherapy, KLE College of Physiotherapy, Hubballi, Karnataka, India after obtaining ethics approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee, reference number JGMMMCIEC/60/2024, from September 14, 2024, to October 14, 2024. A convenience sampling method was used to select the samples and the sample size was calculated based on the prevalence of CP in India [1,3].

Inclusion and Exclusion criteria: The study included children aged 4-12 years diagnosed with CP of either gender and their primary caregivers. The KLE Hubli Cooperative Hospital, along with other medical facilities, special schools and rehabilitation centres in and around Hubballi-Dharwad, Karnataka, India were the sources of the qualifying participants. The study excluded primary caregivers who did not understand Kannada and lacked an effective communication framework.

Study Procedure

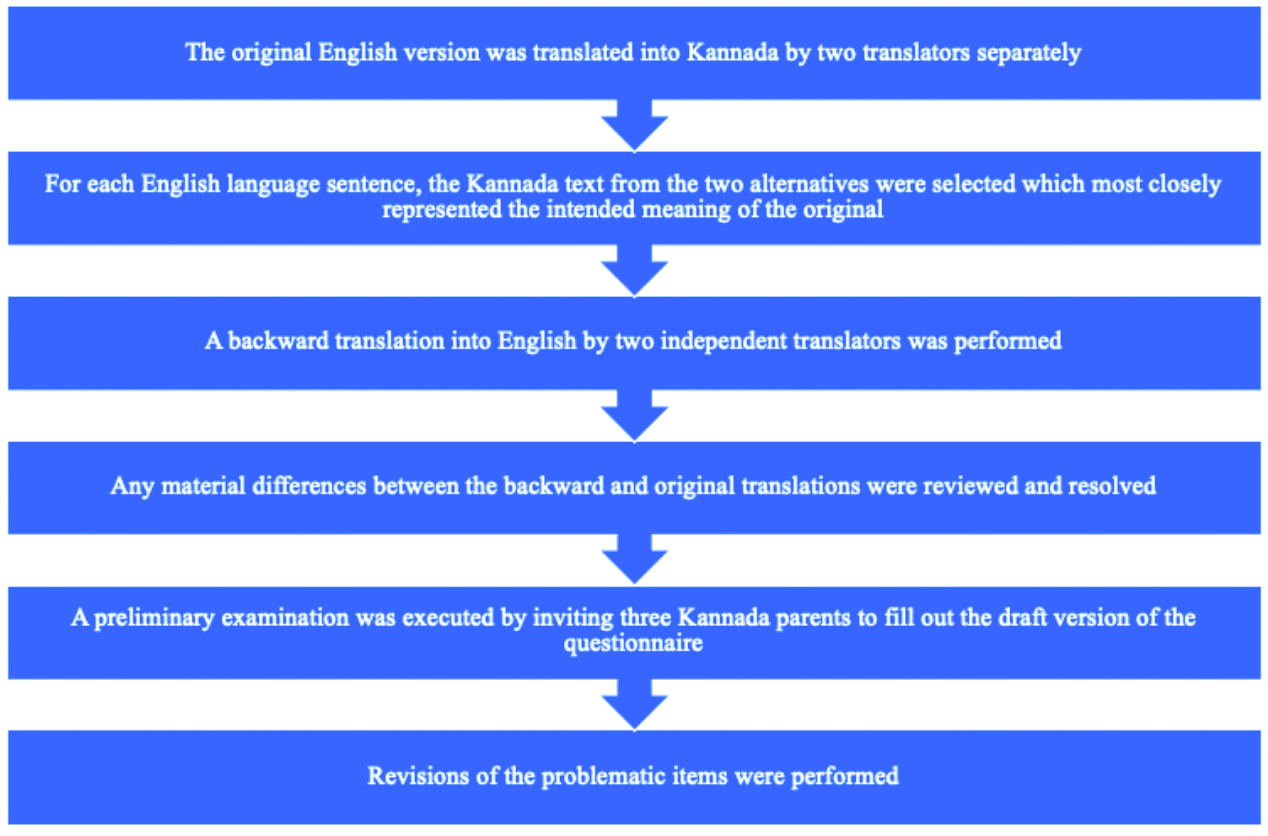

Formal authorisation was obtained from the primary author to translate and validate the original English version of the CP QOL-Child Primary Caregiver (4-12 years) form into Kannada. The translation adhered to the guidelines outlined in the CP QOL Translation Manual [13], which consists of six steps. Two different translators translated the original English text into Kannada and out of the two translations, we chose the Kannada text for each English sentence that most accurately captured the original meaning.

Three participants were asked to fill out the draft form of the questionnaire as part of an initial assessment; any problematic items were addressed through revisions. Two separate translators performed a back-translation into English as a quality control procedure and any notable differences between the original and the back-translation were examined and corrected. According to all of the study’s authors, the translated Kannada questionnaire was clear and simple for participants to understand at every stage of the translation process. The final translated questionnaire was approved by the original author and made available on the official CP QOL website at the following link: [CPQOL-Child-Kannada-Primary-Caregiver-4-12-Years.pdf] (https://www.ausacpdm.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/CPQOL-Child-Kannada-Primary-Caregiver-4-12-Years.pdf). The steps of translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the questionnaire are illustrated in [Table/Fig-1].

Steps of translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the questionnaire.

A single therapist, who was trained to administer the translated questionnaire, conducted interviews through both face-to-face and telephonic methods to maintain homogeneity in the data. Demographic data included the child’s age, gender, latest GMFCS levels [14] and type of CP [15].

The primary caregiver CP QOL questionnaire comprises 66 items in nine categories: family and friends, communication, health, participation, access to services, special equipment, pain and bother, final questions about your child and your health. For the purpose of analysing psychometric properties, it was divided into seven more general domains: Participation and Physical Health (11 items), Emotional well-being and self-esteem (6 items), social well-being and acceptance (12 items), functioning (12 items), pain and impact of disability (8 items), family health (4 items) and access to services (12 items). With the exception of one question in domain 6 about pain and the impact of impairment, which is assessed on a 5-point scale (from 1 to 5), most of the items are rated on a 9-point scale (from 1 to 9). According to the CP QOL-Child Manual, scores for each domain were averaged and then converted to a scale from 0 to 100 [16].

Statistical Analysis

Frequency, percentage, mean and standard deviation were used to summarise the gathered data. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was utilised to evaluate the internal consistency of CP-QOL scores, with a value greater than 0.7 deemed indicative of internal consistency and response validity. GMFCS levels were used to compare CP-QOL using the Kruskal-Wallis “H” test. Multiple comparisons of CP-QOL based on GMFCS levels were conducted using the Shirley-Williams post-hoc test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 29.0 software (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL) was used to analyse the data.

Results

Data were collected from 50 primary caregivers using a translated Kannada questionnaire. The mean age of the children was reported as 8.1±2.3 years. The demographic data of the children with CP and their primary caregivers are presented in [Table/Fig-2].

Demographic data of the CP child and primary caregivers (N=50).

| Demographics characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|

| Age of the patient | 4-6 years | 17 (34) | 34% |

| 7-9 years | 16 (32) | 32% |

| 10-12 years | 17 (34) | 34% |

| Gender | Male | 30 | 60% |

| Female | 20 | 40% |

| Type of CP | Spastic quadriplegic | 36 | 72% |

| Diplegic | 13 | 26% |

| Ataxic | 1 | 2% |

| GMFCS level | I | 0 | 0 |

| II | 3 | 6% |

| III | 4 | 8% |

| IV | 28 | 56% |

| V | 15 | 30% |

| Informant | Mother | 44 | 88% |

| Father | 6 | 12% |

GMFCS: Gross motor functional classification scale

Family health had moderate reliability (0.687), while pain and the impact of disability had very good reliability (0.882) [Table/Fig-3]. A statistically significant difference was found between GMFCS levels and the six domains of CP QOL, except for pain and the impact of disability. The QOL was significantly lower at levels IV and V, particularly in domains such as social well-being and acceptance, functioning, participation and physical health, emotional well-being and self-esteem, access to services and family health [Table/Fig-4].

Assessment and psychometric properties of the Kannada CP QOL-Child questionnaire for primary caregivers.

| CP QOL domains | QOL score (mean±SD) | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|

| Social well-being and acceptance | 34.9±2.9 | 0.746 |

| Functioning | 35.5±2.9 | 0.745 |

| Participation and physical health | 36.5±3.7 | 0.726 |

| Emotional well-being and self-esteem | 37.3±3.1 | 0.738 |

| Access to services | 40.3±9.6 | 0.704 |

| Pain and impact of disability | 69.6±8.3 | 0.882 |

| Family health | 38.8±9.0 | 0.687 |

| CP QOL (Overall) | 41.8±4.2 | |

CP QOL: Cerebral palsy quality of life; QOL: Quality of life

Comparison of CP QOL according to GMFCS levels.

| CP QOL | GMFCS level | p-value |

|---|

| II | III | IV | V |

|---|

| Social well-being and acceptance | 38.9±0.5 | 39.4±0.3 | 35.5±2.0* | 31.9±0.9* | <0.001 |

| Functioning | 40.1±1.9 | 40.6±1.5 | 36.0±1.5* | 32.4±1.2* | <0.001 |

| Participation and physical health | 42.8±3.3 | 41.8±2.0 | 37.4±1.7* | 32.2±1.5* | <0.001 |

| Emotional well-being and self-esteem | 41.9±1.4 | 41.7±1.3 | 38.3±0.9* | 33.2±1.4* | <0.001 |

| Access to services | 50.0±0.8 | 49.8±0.4 | 45.4±2.3* | 26.4±2.2* | <0.001 |

| Pain and impact of disability | 70.5±4.2 | 75.0±6.9 | 67.7±8.6 | 71.5±8.2 | 0.282 |

| Family health | 58.5±0.3 | 52.8±9.7 | 39.5±4.3* | 29.9±1.4* | <0.001 |

| CP QOL (Overall) | 49.0±0.6 | 48.7±1.9 | 42.8±1.5* | 36.8±1.4* | <0.001 |

(*Significant); Bold numbers indicate significant difference (p<0.05) was found among the GMFCS levels and the various domains of CP QOL; (Kruskal Wallis “H” test); *Significant (p<0.05) vs. GMFCS level-II (Shirley-William’s post-hoc test)

Discussion

The CP is a progressive disorder in which the QoL is lower in affected children compared to typically developing children. To effectively measure QoL in this population, it is crucial to address several methodological challenges, particularly communication difficulties and cognitive impairments, which may hinder their ability to self-report. Therefore, offering assessment tools that can be completed by parents or caregivers is advantageous. When self-reporting is not feasible, QoL assessments can be conducted by primary caregivers, who often possess a deep understanding of their children’s experiences and can provide accurate insights. Thus, the study translated and validated the CP QOL-Child (Primary Caregiver) for children aged 4-12 years in Kannada.

Regarding the rating scale’s internal consistency, the original CP QOL instrument for primary carers had Cronbach’s α coefficients ranging from 0.74 to 0.927. Cronbach’s α values in Hindi were greater than 0.9 [17] and they ranged from 0.72 to 0.89 for Japanese [18]. With a low value of 0.687 in family health, the Cronbach’s α (range: 0.687-0.882) of the Kannada CP QOL-Child Primary Carer (ages 4-12) has demonstrated moderate to very good reliability. Similar findings were obtained in an analysis of internal consistency for the domains “pain and impact of disability” and “family health” by Waters E et al., and Vadivelan K and Sekar P [19,20].

In the age group of 4–12 years, a greater prevalence of quadriplegic CP was found (72%), with GMFCS level IV accounting for 56%. A study by Bhati P et al., found the highest incidence of quadriplegic CP in New Delhi [21]. In contrast, another study conducted in Gujarat found a predominance of diplegic CP [22].

In the current study, the QOL was significantly lower in GMFCS levels IV and V. A similar study conducted in Tamil Nadu stated that with higher levels of GMFCS, QOL was lower, especially at levels IV and V [20]. Gharaborghe SN et al., reported that an increase in GMFCS in children with CP has a considerable effect on their QOL [23]. Mutoh T et al., showed similar results, indicating that the domains of pain and impact disability had no effect on GMFCS levels [18].

The overall QOL, when assessed using the Kannada CP QOL-Child Primary Caregiver, was found to be 41.8±4.2. A score of 37.67±4.57 was found in Kattankulathur, Tamil Nadu [20]. The study carried out in the Child Development Clinic of a tertiary care hospital in North India found an overall QOL of 38.29±5.2 [24]. To generalise the results regarding the influence of GMFCS level and gender on QOL, a larger sample size should be obtained for future studies.

Limitation(s)

Samples from different geographical areas of Karnataka would further strengthen the findings of the study. The current study did not address the education level of the primary caregivers, which might have influenced the QOL.

Conclusion(s)

The study concluded that the Kannada CP QOL - Child Primary Caregivers (ages 4 to 12 years) is a valid and reliable measure that can be used to assess QoL in the Kannada-speaking community. The QOL decreased as GMFCS levels increased, particularly at levels IV and V. There was no significant difference in pain and the impact of disability across the GMFCS levels.

GMFCS: Gross motor functional classification scale

CP QOL: Cerebral palsy quality of life; QOL: Quality of life

(*Significant); Bold numbers indicate significant difference (p<0.05) was found among the GMFCS levels and the various domains of CP QOL; (Kruskal Wallis “H” test); *Significant (p<0.05) vs. GMFCS level-II (Shirley-William’s post-hoc test)

Author Declaration:

Financial or Other Competing Interests: None

Was Ethics Committee Approval obtained for this study? Yes

Was informed consent obtained from the subjects involved in the study? Yes

For any images presented appropriate consent has been obtained from the subjects. NA

Plagiarism Checking Methods: [Jain H et al.]

Plagiarism X-checker: Dec 05, 2024

Manual Googling: Jan 27, 2025

iThenticate Software: Jan 29, 2025 (12%)

[1]. Kerr Graham H, Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Dan B, Lin JP, Damiano DL, Cerebral palsyNat Rev Dis Primers 2016 2:1508210.1038/nrdp.2015.8227188686PMC9619297 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Brooks JC, Strauss DJ, Shavelle RM, Tran LM, Rosenbloom L, Wu YW, Recent trends in cerebral palsy survival. Part I: Period and cohort effectsDev Med Child Neurol 2014 56(11):1059-64.10.1111/dmcn.1252024966011 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Korzeniewski SJ, Slaughter J, Lenski M, Haak P, Paneth N, The complex aetiology of cerebral palsyNat Rev Neurol 2018 14(9):528-43.10.1038/s41582-018-0043-630104744 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Chauhan A, Singh M, Jaiswal N, Agarwal A, Sahu JK, Singh M, Prevalence of cerebral palsy in Indian children: A systematic review and meta-analysisIndian J Pediatr 2019 86(12):1124-30.10.1007/s12098-019-03024-031300955 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5]. Jahan I, Muhit M, Hardianto D, Laryea F, Amponsah SK, Chhetri AB, Epidemiology of malnutrition among children with cerebral palsy in low- and middle-income countries: Findings from the Global LMIC CP RegisterNutrients 2021 13(11):367610.3390/nu1311367634835932PMC8619063 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric propertiesSoc Sci Med 1998 46(12):1569-85.10.1016/S0277-9536(98)00009-49672396 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. The World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment (WHOQOL): Position paper from the World Health OrganizationSoc Sci Med 1995 41(10):1403-09.10.1016/0277-9536(95)00112-K8560308 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: Time for a revolutionLancet Glob Health 2018 6:e1196-252.10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30386-330196093 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. dos Santos AN, Pavão SL, de Campos AC, Rocha NACF, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health in children with cerebral palsyDisabil Rehabil 2012 34(12):1053-58.10.3109/09638288.2011.63167822107334 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Huisman ERCM, Morales E, van Hoof J, Kort HSM, Healing environment: A review of the impact of physical environmental factors on usersBuilding and Environment 2012 58:70-80.10.1016/j.buildenv.2012.06.016 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[11]. Gilson KM, Davis E, Reddihough D, Graham K, Waters E, Quality of life in children with cerebral palsy: Implications for practiceJ Child Neurol 2014 29(8):1134-40.10.1177/088307381453550224870369 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[12]. Rapp M, Eisemann N, Arnaud C, Ehlinger V, Fauconnier J, Marcelli M, Predictors of parent-reported quality of life of adolescents with cerebral palsy: A longitudinal studyRes Dev Disabil 2017 62:259-70.10.1016/j.ridd.2016.12.00528110883 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13]. Waters E, Davis E, Translation Manual. Version 2 2018 Nov 23 [cited 2025 Jan 16]. Available from: https://mcri.figshare.com/articles/journal_contribution/Translation_Manual_Version_2/7284443/1 [Google Scholar]

[14]. Paulson A, Vargus-Adams J, Overview of four functional classification systems commonly used in cerebral palsyChildren (Basel) 2017 4(4):3010.3390/children404003028441773PMC5406689 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[15]. Vitrikas K, Dalton H, Breish D, Cerebral palsy: An overviewAm Fam Physician 2020 101(4):213-20. [Google Scholar]

[16]. AusACPDM [Internet][cited 2025 Jan 16]. The Cerebral Palsy Quality of Life Questionnaire. Available from: https://www.ausacpdm.org.au/research/cpqol/ [Google Scholar]

[17]. Das S, Aggarwal A, Roy S, Kumar P, Quality of life in Indian children with cerebral palsy using cerebral palsy-quality of life questionnaireJ Pediatr Neurosci 2017 12(3):251-54.10.4103/jpn.JPN_127_1629204200PMC5696662 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[18]. Mutoh T, Mutoh T, Kurosaki H, Shimomura H, Taki Y, Development and exploration of a Japanese version of the cerebral palsy quality of life for children questionnaire for primary caregivers: A pilot studyJ Phys Ther Sci 2019 31(9):724-28.10.1589/jpts.31.72431631945PMC6751053 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[19]. Waters E, Davis E, Mackinnon A, Boyd R, Graham HK, Kai Lo S, Psychometric properties of the quality of life questionnaire for children with CPDev Med Child Neurol 2007 49(1):49-55.10.1017/S0012162207000126.x17209977 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[20]. Vadivelan K, Sekar P, Assessment of proxy quality of life in children with cerebral palsy: A cross-sectional studyPediatr Pol 2021 95(4):212-15.10.5114/polp.2020.103497 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[21]. Bhati P, Sharma S, Jain R, Rath B, Beri S, Gupta VK, Cerebral palsy in north indian children: Clinico-etiological profile and comorbiditiesJ Pediatr Neurosci 2019 14(1):30-35.10.4103/JPN.JPN_46_1831316640PMC6601115 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[22]. Ramanandi VH, Shukla YU, Socio-demographic and clinical profile of pediatric patients with cerebral palsy in Gujarat, IndiaBulletin of Faculty of Physical Therapy 2022 27(1):1910.1186/s43161-022-00077-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[23]. Gharaborghe SN, Sarhady M, Hosseini SMS, Mortazavi SS, Quality of life and gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy (Aged 4-12)Iranian Rehabilitation Journal 2015 13(3):58-62. [Google Scholar]

[24]. Jain R, Arun P, Ramanjot Translation and adaptation of cerebral palsy quality of life primary caregiver - teen questionnaire in north Indian population: CP-QOL-Teen (Hindi)Indian J Pediatr 2024 91(10):109010.1007/s12098-024-05189-938898195 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]