Dejerine-Roussy Syndrome: Understanding Chronic Thalamic Pain

Saket S Toshniwal1, Jiwan Kinkar2, Yatika Chadha3, Sourya Acharya4, Sunil Kumar5

1 Postgraduate Resident, Department of General Medicine, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research, Wardha, Maharashtra, India.

2 Professor, Department of Neurology, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research, Wardha, Maharashtra, India.

3 Postgraduate Resident, Department of Psychiatry, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research, Wardha, Maharashtra, India.

4 Professor, Department of General Medicine, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research, Wardha, Maharashtra, India.

5 Professor, Department of General Medicine, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research, Wardha, Maharashtra, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Saket S Toshniwal, Postgraduate Resident, Department of General Medicine, Datta Meghe Institute of Higher Education and Research, Wardha-442107, Maharashtra, India.

E-mail: toshniwalsaket@gmail.com

Allodynia, Central pain, Hyperalgesia, Neuropathic pain

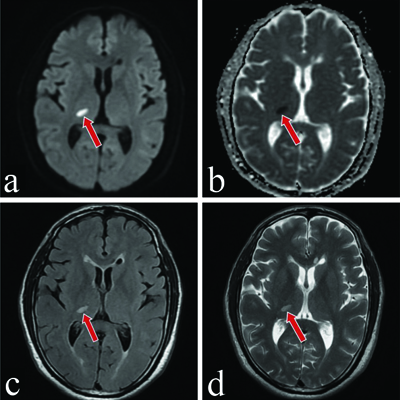

A 50-year-old male, known to be hypertensive and non compliant with medications, with a significant past history of stroke three months ago, presented to the hospital with chief complaints of persistent burning sensations in his left arm and leg, as well as his entire face. He also reported episodes of sharp shooting pain in these regions lasting for a few seconds. Additionally, he complained of increased sensitivity to touch and intolerance to any painful stimuli, experiencing pain even upon touch, which caused significant discomfort and led to feelings of depression. These complaints have been present since he had a stroke three months ago, and they have gradually progressed to a stage where the pain has become intolerable. A Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the brain performed at the time of the stroke showed a lesion in the ventroposterior lateral thalamic region, leading to the diagnosis of the debilitating condition known as Dejerine-Roussy syndrome, as shown in [Table/Fig-1a-d].

a) Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of brain Diffusion Weighted Imaging (DWI) showing diffusion restriction in the right thalamus marked with a red arrow. b) Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of brain Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) showing ADC fall in right thalamus marked with a red arrow. c) Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of brain Fluid Attenuated Inversion Recovery (FLAIR) showing hyperintense lesion in right thalamus marked with a red arrow. d) Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of brain T2 weighted showing hyperintense lesion in right thalamus marked with a red arrow.

The patient was started on anticonvulsant drug therapy (tablet pregabalin 75 mg once at night) for the management of his neuropathic pain, along with a tricyclic antidepressant (tablet amitriptyline 10 mg once at night), and was asked to follow-up after a week. On the follow-up after seven days, the patient reported no significant relief in pain. Serotonin and Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) (tablet duloxetine 60 mg once daily) were added to his treatment. Subsequent follow-ups showed a reduction in the intensity of his pain, but it was still persistent, disrupting his day-to-day activities and causing mental frustration. Rehabilitation was further advised for functional improvement and the emotional well-being of the patient. The rehabilitation process, along with ongoing pain management, was initiated by educating the patient about this debilitating disorder, its prognosis, and all available treatment options such as physiotherapy, psychotherapy, as well as various invasive and non invasive non pharmacological treatments like deep brain stimulation, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, motor cortex stimulation, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. In this patient, physiotherapy and psychotherapy were initiated to address the emotional stress associated with this disorder. Desensitisation therapy was also started by identifying various triggers of the patient’s pain stimuli and implementing gradual exposure therapy to painful stimuli in a controlled environment where the patient feels safe and supported, along with relaxation techniques such as deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation. This minimal stimulus was progressively increased to more intense stimuli to help the patient adapt and desensitise to painful triggers, and the patient was advised to practice these techniques at home. Regular follow-up, along with a multidisciplinary approach involving healthcare professionals such as physical therapists, occupational therapists, pain specialists, psychologists and social workers, was crucial in managing the patient. Although the pain persisted with decreasing intensity in further follow-ups, the patient became acclimated and coped well with his disorder.

Discussion

A rare central neuropathic pain syndrome that develops following a ventroposterolateral thalamic infarction is known as central poststroke pain, often referred to as thalamic pain syndrome or Dejerine-Roussy syndrome. The thalamus serves as the relay center for the somatosensory pathway, and any lesion that interferes with the spinothalamic tract along its path in the subcortical, capsular, lower brain stem, or lateral medullary regions can exacerbate Dejerine-Roussy syndrome symptoms and cause “pseudo-thalamic” pain [1]. About 25% of individuals with sensory strokes caused by thalamic lesions develop thalamic stroke with Dejerine-Roussy syndrome. Dejerine-Roussy syndrome affects roughly 11% of those over 80, making older stroke victims more likely to have the illness [1]. These figures emphasise how important it is to comprehend this illness and treat it within the framework of stroke treatment and rehabilitation.

Neuropathic pain, sometimes characterised as burning, tingling, or shooting sensations, is a common symptom in patients with thalamic stroke and Dejerine-Roussy syndrome. This pain is typically unilateral and can affect various parts of the body, including the face, arm, and leg on the opposite side of the stroke-affected thalamus. Additionally, patients may experience sensory abnormalities such as increased sensitivity to touch (allodynia) and pain from non painful stimuli (hyperalgesia), further contributing to their discomfort and distress [2].

Dejerine-Roussy syndrome, also known as central poststroke pain, causes persistent pain and may be lifelong. Medical management of central poststroke pain includes:

Pain management: Targeted interventions such as medications (e.g., anticonvulsants, antidepressants, or opioids), nerve blocks, and neurostimulation techniques (e.g., spinal cord stimulation) may be utilised to alleviate neuropathic pain.

Physical and occupational therapy: Rehabilitation programs focusing on desensitisation, sensory re-education, and motor function improvement can aid in enhancing patients’ functional abilities and reducing disability.

Psychological support: Given the chronic and distressing nature of the condition, psychological interventions like cognitive behavioural therapy and counselling can help patients cope with the emotional impact of persistent pain [3].

Various invasive and non invasive non pharmacological treatments have been attempted for pain relief, such as deep brain stimulation, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, motor cortex stimulation, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. Cases have been reported with successful use of deep brain stimulation in treating Dejerine-Roussy syndrome [3]. Additionally, antiplatelet agents like cilostazol and vestibular caloric stimulation are considered the future of central stroke pain management and are currently under trial [4]. Ramachandran VS et al., reported two cases of refractory neuropathic pain responding successfully to cold vestibular caloric stimulation, which is seen as the future of central stroke pain management [5]. Long-term follow-up care involves regular assessments of pain intensity, functional status, and treatment response. Healthcare providers monitor for any signs of medication side-effects, disease progression, or the development of co-morbidities. Adjustments to the treatment plan and supportive care are made based on the individual’s evolving needs and responses to interventions. Ongoing research in the field of neurology and rehabilitation continues to explore novel treatment modalities and therapeutic approaches for thalamic stroke with Dejerine-Roussy syndrome [4]. In conclusion, thalamic stroke with Dejerine-Roussy syndrome represents a challenging aspect of poststroke care, characterised by persistent neuropathic pain and sensory disturbances. By integrating comprehensive follow-up care, including medical management, rehabilitation, and psychological support, healthcare providers can strive to enhance the quality of life for individuals affected by this condition.

Author Declaration:

Financial or Other Competing Interests: None

Was informed consent obtained from the subjects involved in the study? Yes

For any images presented appropriate consent has been obtained from the subjects. Yes

Plagiarism Checking Methods: [Jain H et al.]

Plagiarism X-checker: Mar 31, 2024

Manual Googling: May 17, 2024

iThenticate Software: May 22, 2024 (8%)

[1]. Krishnan R, Chaudhari DM, Renjen PN, Mishra A, Priyal Pandey S, Déjerine-Roussy syndrome presenting with atypical involuntary movementsInt J Neurosci 2024 01:03Epub ahead of print10.1080/00207454.2024.230287038180031 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Guédon A, Thiebaut JB, Benichi S, Mikol J, Moxham B, Plaisant O, Dejerine-Roussy syndrome: Historical casesNeurology 2019 93(14):624-29.10.1212/WNL.000000000000820931570637 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Alves RV, Asfora WT, Deep brain stimulation for Dejerine-Roussy syndrome: Case reportMinim Invasive Neurosurg 2011 54(4):183-86.Epub 2011 Sep 1510.1055/s-0031-128083321922448 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Urits I, Gress K, Charipova K, Orhurhu V, Freeman JA, Kaye RJ, Diagnosis, treatment, and management of Dejerine-Roussy syndrome: A comprehensive reviewCurr Pain Headache Rep 2020 24(9):4810.1007/s11916-020-00887-332671495 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5]. Ramachandran VS, McGeoch PD, Williams L, Can vestibular caloric stimulation be used to treat Dejerine-Roussy syndrome? Med Hypotheses 2007 69(3):486-88.Epub 2007 Feb 2310.1016/j.mehy.2006.12.03617321064 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]