Synovial Chondromatosis (SC), previously known as synovial osteochondromatosis, is usually an uncommonly encountered condition. Pathologically, the condition involves the formation of multiple cartilaginous nodules that arise from the synovium of facet joints and may detach from the synovium to form loose bodies in or around the joint space. While X-rays help in the early detection of loose bodies in SC, advanced diagnostic modalities such as Computed Tomography (CT) scans and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) aid in preoperative diagnosis and work-up. Authors hereby, report a unique case of secondary SC of the elbow joint in a 50-year-old male patient who presented with complaints of swelling, chronic elbow pain, and joint stiffness with restricted movement following an old traumatic injury. The patient was clinically misdiagnosed as having ‘Myositis Ossificans’ due to the history of massaging the elbow joint following trauma by a local practitioner. However, radiological investigations revealed multiple intra- and extra-articular loose bodies of varying sizes and stages of calcification, leading to a diagnosis of ‘Secondary SC’. SC is a rare entity that is often misdiagnosed during clinical examinations. Therefore, extensive radiological evaluation is necessary for the accurate and early diagnosis of the condition. Early surgical management can restore the Range of Motion (ROM) of the affected joint and prevent secondary osteoarthritic changes.

Computed tomography scan, Loose bodies, Synovium, X-ray

Case Report

A 50-year-old male patient presented with complaints of intermittent, dull-aching, activity-related pain and swelling in the left elbow for the past year. The onset was insidious, with a slow and gradual progression in intensity. The pain resolved with rest. The patient also reported joint stiffness and difficulty in performing elbow flexion and extension, along with a progressive decrease in the ROM at the left elbow joint. He had a history of a traumatic injury to the left elbow two years ago, the nature of which was unknown, for which local massaging and painkillers were advised.

Physical examination of the left elbow revealed a tender swelling around the joint. No evidence of local rise in temperature was noted. The skin appeared dry without erythema. The ROM was limited to 45° to 120° of flexion, with pain at the endpoints of motion. The pronation and supination ROM were preserved. There was mildly painful crepitation with ROM, and instability testing was negative. The gross neurovascular examination was normal.

Laboratory investigations revealed normal Total Leukocyte Count (TLC) at 5600/mm3. The Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) was 7 mm/hr, C-Reactive Protein (CRP) was 3 mg/L, and Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) factor (RA 12U/mL) was also within normal limits. Given the patient’s history of trauma followed by local massaging of the area, the treating physician considered a clinical diagnosis of myositis ossificans [1].

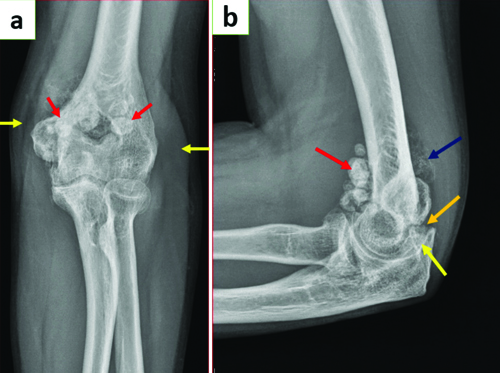

Static radiographs of the left elbow joint [Table/Fig-1a] reveal multiple well-defined round calcified extra-articular loose bodies around the elbow joint, accompanied by mild soft tissue swelling. The lateral view X-ray of the elbow joint [Table/Fig-1b] shows multiple extra-articular (both calcified and non calcified) loose bodies of varying sizes at the anterior and posterior aspects of the elbow joint. In addition to the extra-articular loose bodies, intra-articular loose bodies were also observed, resulting in the widening of the ulnohumeral joint space.

a) X-ray of left elbow joint in extension AP view showing multiple well-defined round calcified extra-articular loose bodies around the elbow joint (red arrows). Mild soft-tissue swelling around the joint is also noted (yellow arrows); b) X-ray of left elbow joint in flexion lateral view showing multiple extra-articular calcified (red arrow), extra-articular non calcified (blue arrow) loose bodies of varying sizes seen at the anterior and posterior aspects of the elbow joint. Intra-articular loose bodies (orange arrow) also seen resulting in widening of ulno-humeral joint space (yellow arrow).

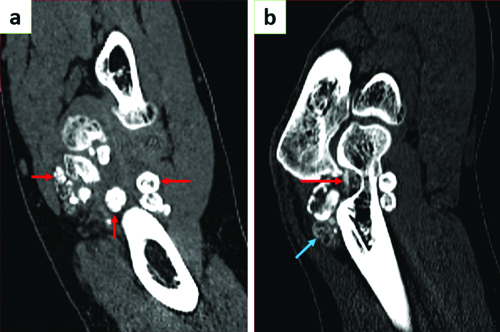

A Non Contrast Computed Tomography (NCCT) scan of the left elbow joint [Table/Fig-2a] reveals multiple loose bodies of varying sizes around the elbow joint in different stages of ossification, characterised by concentric rings of calcification. Intra-articular loose bodies [Table/Fig-2b] in the olecranon fossa are also identified. Minimal effusion was noted surrounding the elbow joint.

NCCT scan of the left elbow joint: a) Coronal section showing multiple loose bodies around the elbow joint of varying sizes (red arrows) with minimal effusion; b) Sagittal section showing loose bodies with varying degrees of calcifications. Concentric ring-like calcifications are seen (blue arrow). Intra-articular loose bodies (red arrow) in the olecranon fossa.

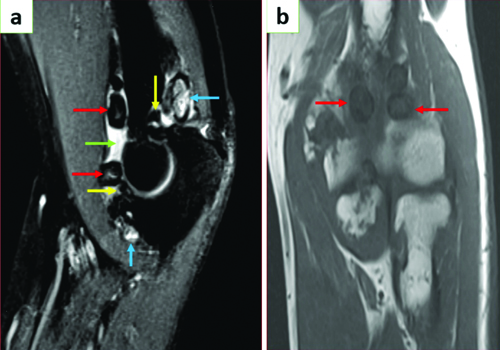

MRI of the elbow joint [Table/Fig-3a,b] shows T2 hyperintense joint effusion with multiple T1 and T2 low signal extra- and intra-articular loose bodies in the elbow joint. A few T2 hyperintense loose bodies are noted due to a lack of mineralisation. The ligaments around the elbow joint appear intact, and there is no evidence of bone marrow oedema or significant soft tissue swelling.

MRI of the elbow joint: a) Sagittal T2 and; b) Coronal T1 sections of elbow joint showing multiple ossified extra-articular (red arrows) and intra-articular (yellow arrows) loose bodies with central hyperintensity in T2WI. Few non-ossified T2 hyperintense loose bodies noted (blue arrows). Joint effusion is seen (green arrow).

Based on the clinical history of a previous traumatic injury to the elbow joint and various radiological investigations revealing joint effusion with joint space widening, multiple extra-articular and intra-articular loose bodies of varying sizes and different stages of mineralisation, arising from the synovium and with unremarkable surrounding soft tissue structures, a diagnosis of secondary SC was made. At the time of presentation, the patient did not exhibit significant disability and was advised to have regular follow-up visits to the orthopaedics Outpatient Department (OPD) to monitor the progression of the disease. Operative procedures were to be planned later in the disease process; however, the patient failed to follow-up due to economic constraints.

Discussion

The SC is a rare condition affecting the synovial membrane of joints, tendon sheaths, and bursae. Although the condition itself is non malignant, it can lead to significant joint dysfunction and disability. Historically, and across various literature, SC has been referred to by various names, including synovial osteochondromatosis, synovial chondrosis, synovial chondrometaplasia, and articular ecchondrosis [2-5]. Although the condition is usually benign, very few cases of transformation to chondrosarcoma have been reported [6]. The disease typically affects patients in their third to fifth decades of life [3]. The knee is the most commonly affected joint in 60-70% of cases. Other affected joints, in descending order of frequency, are the hip, shoulder, elbow, ankle, and wrist [7-10]. SC is distinguished by the presence of multiple cartilaginous loose bodies within the joint. It is categorised into two types: primary and secondary. Primary SC is idiopathic and typically affects individuals in their third or fourth decade of life. In contrast, secondary SC arises from factors such as repeated trauma, osteochondritis dissecans, Charcot’s joint disease, or other inflammatory joint conditions, and is generally seen in individuals in their fifth or sixth decades [11]. The disease involves cartilaginous metaplasia of mesenchymal cells adjacent to the synovial cells, leading to the formation of nodules. These nodules can eventually detach from the synovial membrane and become loose bodies within the joint. Over time, these loose bodies may fuse and undergo calcification. Clinically, patients present with joint pain, swelling, and reduced ROM [12].

Imaging studies play a crucial role in the preoperative assessment of SC. Radiographs typically show numerous calcified loose bodies in 70-95% of cases of primary SC [13-16]. These calcifications are often evenly distributed throughout the joint and present a characteristic appearance, being numerous and similar in shape and size. The mineralisation often follows a distinctive chondroid ring-and-arc pattern [17]. Differentiating primary SC from the secondary form using MRI can be challenging. Secondary SC usually occurs in the context of osteoarthritis, whereas primary SC, which is chronic, can lead to the development of osteoarthritis over time [17]. Nevertheless, several key differences can aid in diagnosis [18]. Secondary SC often features osteochondral fragments within the joint that vary in size and number, indicating different periods of formation and calcification. In contrast, primary SC is characterised by uniformly distributed fragments that are consistent in size and shape. Additionally, secondary SC may show multiple rings of calcification on radiographs, whereas the primary disease typically presents with a single ring. Furthermore, secondary SC is usually accompanied by underlying joint abnormalities, such as osteoarthritis, which helps to distinguish it from the primary form [2,19,20].

Very few cases of secondary SC of the elbow joint have been reported in the literature to date, making present case a rare entity. In present case, a history of a traumatic event was followed by a gradual decrease in ROM, along with osteoarthritic changes. Multiple intra-articular and extra-articular loose bodies of varying sizes, in different stages of ossification and showing concentric calcifications on imaging, were observed. A similar case of SC of the elbow joint was reported by Griesser MJ et al., involving a patient who experienced intermittent elbow joint pain, stiffness, and decreased ROM for four years [21]. MRI revealed a large joint effusion with multiple loose bodies in the olecranon and coronoid fossa. Complete synovectomy and removal of multiple loose bodies were performed.

Another case reported by Mo J et al., involved a 14-year-old gymnast who had bilateral elbow joint involvement [22]. Radiographs revealed multiple calcified densities surrounding the anterior and posterior aspects of the elbow joints. Additionally, sclerotic changes in the articular surface and decreased joint space were noted in the CT findings. However, no intra-articular loose bodies were identified. Capsulotomy, followed by the removal of all loose bodies, was performed, and the proliferative synovium was excised.

Conclusion(s)

The SC typically involves large joints and presents with joint effusion. The joints may appear deformed due to swelling or synovial hypertrophy. This pathology can result in severe disability and dysfunction.

Author Declaration:

Financial or Other Competing Interests: None

Was informed consent obtained from the subjects involved in the study? Yes

For any images presented appropriate consent has been obtained from the subjects. Yes

Plagiarism Checking Methods: [Jain H et al.]

Plagiarism X-checker: Jun 06, 2024

Manual Googling: Jul 27, 2024

iThenticate Software: Aug 26, 2024 (09%)

[1]. Larson CM, Almekinders LC, Karas SG, Garrett WE, Evaluating and managing muscle contusions and myositis ossificansPhys Sportsmed 2002 30:41-50.10.3810/psm.2002.02.17420086513 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Crotty JM, Monu JU, Pope TL Jr, Synovial osteochondromatosisRadiol Clin North Am 1996 34:327-42.10.1016/S0033-8389(22)00471-78633119 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Dorfman HD, Czerniak B, Synovial lesionsIn: Bone tumors 1998 St Louis, MoMosby:1041-1086. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Fanburg-Smith JC, Cartilage and bone-forming tumors and tumor-like lesions. In: Miettinen M, edDiagnostic soft-tissue pathology 2003 Philadelphia, PaChurchill-Livingstone:403-25. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Jaffe HL, Tumors and tumorous conditions of the bones and jointsAcademic Medicine 1959 34(1):7210.1097/00001888-195901000-00023 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[6]. Bojanić I, Vuletić LB, Troha I, Smoljanović T, Borić I, Seiwerth S, Synovial chondromatosisLijec Vjesn 2010 132(3-4):102-10. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Evans S, Boffano M, Chaudhry S, Jeys L, Grimer R, Synovial chondrosarcoma arising in synovial chondromatosisSarcoma 2014 2014:64793910.1155/2014/64793924737946 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Tokis AV, Andrikoula SI, Chouliaras VT, Vasiliadis HS, Georgoulis AD, Diagnosis and arthroscopic treatment of primary synovial chondromatosis of the shoulderArthroscopy 2007 23(9):1023.e1-5.10.1016/j.arthro.2006.07.00917868844 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Aydogan NH, Kocadal O, Ozmeric A, Aktekin CN, Arthroscopic treatment of a case with concomitant subacromial and subdeltoid synovial chondromatosis and labrum tearCase Rep Orthop 2013 2013:63674710.1155/2013/63674724383030 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Chillemi C, Marinelli M, de Cupis V, Primary synovial chondromatosis of the shoulder: clinical, arthroscopic and histopathological aspectsKnee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2005 13(6):483-88.10.1007/s00167-004-0608-315726326 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. Alexander JE, Holder JC, McConnell JR, Fontenot E Jr, Synovial osteochondromatosisAm Fam Physician 1987 35(2):157-61. [Google Scholar]

[12]. Ozmeric A, Aydogan NH, Kocadal O, Kara T, Pepe M, Gozel S, Arthroscopic treatment of synovial chondromatosis in the ankle jointInt J Surg Case Rep 2014 5:1010-13.10.1016/j.ijscr.2014.10.08325460460 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13]. Dufour JP, Hamels J, Maldague B, Noel H, Pestiaux B, Unusual aspects of synovial chondromatosis of the elbowClin Rheumatol 1984 3:247-51.10.1007/BF020307656467866 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[14]. Friedman B, Nerubay J, Blankstein A, Kessker A, Horoszowski H, Case report 439: Synovial chondromatosis (osteochondromatosis) of the right hip: “Hidden” radiologic manifestationsSkeletal Radiol 1987 16(6):504-08.10.1007/BF003505493659999 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[15]. Wittkop B, Davies A, Mangham D, Primary synovial chondromatosis and synovial chondrosarcoma: A pictorial reviewEur Radiol 2002 12:2112-19.10.1007/s00330-002-1318-112136332 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[16]. Zimmerman C, Sayegh V, Roentgen manifestations of synovial osteochondromatosisAm J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1960 83:680-86. [Google Scholar]

[17]. Murphey MD, Vidal JA, Fanburg-Smith JC, Gajewski DA, Imaging of synovial chondromatosis with radiologic-pathologic correlationRadiographics 2007 27(5):1465-88.10.1148/rg.27507511617848703 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[18]. Ho YY, Choueka J, Synovial chondromatosis of the upper extremityJ Hand Surg Am 2013 38(4):804-10.10.1016/j.jhsa.2013.01.04123474166 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[19]. Kransdorf MJ, Murphey MD, Synovial tumorsIn: Imaging of soft-tissue tumors 2006 2nd edPhiladelphia, PaLippincott Williams & Wilkins:412-436. [Google Scholar]

[20]. Villacin AB, Brigham LN, Bullough PG, Primary and secondary synovial chondrometaplasia: Histopathologic and clinicoradiologic differencesHum Pathol 1979 10:439-51.10.1016/S0046-8177(79)80050-7468226 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[21]. Griesser MJ, Harris JD, Likes RL, Jones GL, Synovial chondromatosis of the elbow causing a mechanical block to range of motion: A case report and review of the literatureAm J Orthop 2011 40(5):253-56. [Google Scholar]

[22]. Mo J, Pan J, Liu Y, Feng W, Li B, Luo K, Bilateral synovial chondromatosis of the elbow in an adolescent: A case report and literature reviewBMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2020 21:01-05.10.1186/s12891-020-03322-132534572 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]