The MRKH syndrome is one of the most well-known causes of congenital anomalies of the female reproductive tract, accounting for about 15% of cases. This condition is usually linked to agenesis of the upper two-thirds of the vagina with complete absence or a rudimentary uterus. It affects 1 in 4,000 to 1 in 80,000 live births. Genotypically as well as phenotypically, these females are normal. They also have normal ovarian function with either an absent or rudimentary uterus. In addition to being a possible isolated gynaecologic deformity (type I), MRKH syndrome may also be linked to urinary tract, skeletal (rib, vertebral), and, to a lesser extent, cardiac and auditory abnormalities (type II). Up to 25-50% of those affected may have abnormalities in the urinary tract, such as renal ectopy, dilatations, duplications, and agenesis [1].

Primary amenorrhea, usually occurring between 14 and 16 years, is the most common presenting symptom. Since the ovarian function of these individuals is expected to be normal, the secondary sexual characteristics are also standard, along with normal-appearing external genitalia [1]. If left untreated, the patient may develop severe psychological issues [2]. A thorough clinical examination, abdominal/pelvic ultrasonography, and karyotyping are required for diagnosis, following which the patient and her family are counselled regarding the reconstructive procedure [3]. Therefore, managing vaginal agenesis in patients with MRKH syndrome presents a significant challenge.

Various non surgical and surgical treatments have been described in the literature, such as Frank Serial dilation, Vecchietti’s technique, Abbe McIndoe’s technique, Singapore flap, Gracilis flap, sigmoid or ileal flaps, and expanded vulval flap [4]. The ideal procedure involves creating a vagina that resembles the average vagina as closely as possible. The Abbe McIndoe procedure is the simplest and most popular vaginal reconstruction surgery [5]. Here, a split-thickness skin graft is used to cover a surgically created space between the bladder and rectum, called the neovagina. A stent (vaginal mould) is used to maintain the luminal patency of the neovagina. The Singapore flap creates a sensate and flexible neovagina that enables sexual functioning [6]. The optimum surgical approach has only been the subject of a few investigations, most of which are cross-sectional, single-centre studies with inadequate standardisation and scant follow-up [7,8]. Therefore, the optimal surgical technique is still debated [7]. Thus, the current study compared the Abbe-McIndoe procedure and the Singapore flap for neovaginal reconstruction in 12 patients with MRKH syndrome.

Materials and Methods

The prospective interventional study was conducted in the Department of Plastic Surgery at SRM Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, located in Kattankulathur, Tamil Nadu, India from January 2020 to December 2023. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) with approval number ECR/8881/INST/TN/2013/RR-12.

Inclusion criteria: Patients with congenital vaginal agenesis due to MRKH syndrome, aged 18 years or older and those who provided written informed consent were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria: Patients under 18 years of age, patients with vaginal defects due to causes other than MRKH syndrome and those who did not consent to participate in the study were excluded from the study.

Sample size estimation: The sample size was estimated based on a preliminary pilot study and literature review [9]. This ensured that the study was adequately powered to detect significant differences between the two surgical techniques. A minimum of six patients per group was deemed sufficient, resulting in a total sample size of 12 patients.

Study Procedure

A comprehensive history taking and physical examination determined the aetiology of primary amenorrhea and related anomalies. Following the confirmation of MRKH syndrome through karyotyping and abdominal/pelvic ultrasonography or Computed Tomography (CT), patients were counselled about their diagnosis and potential treatment options. Surgery was performed after obtaining anaesthetic clearance.

The participants were randomly assigned into two groups using block randomisation with a block size of four, ensuring an equal distribution of participants (n=6) in each group. A random number generator was used to assign participants within each block to either:

Group A (n=6): Underwent the Abbe McIndoe procedure.

Group B (n=6): Underwent the Singapore flap procedure.

Presurgical preparation: The patient’s abdomen, perineum, and thighs were prepared. Lower bowel preparation was done the night before and the morning of the surgery. The patient was placed in a lithotomy position after administering spinal anaesthesia. The whole abdomen, perineum, and both thighs were scrubbed with betadine, and the bladder was catheterised.

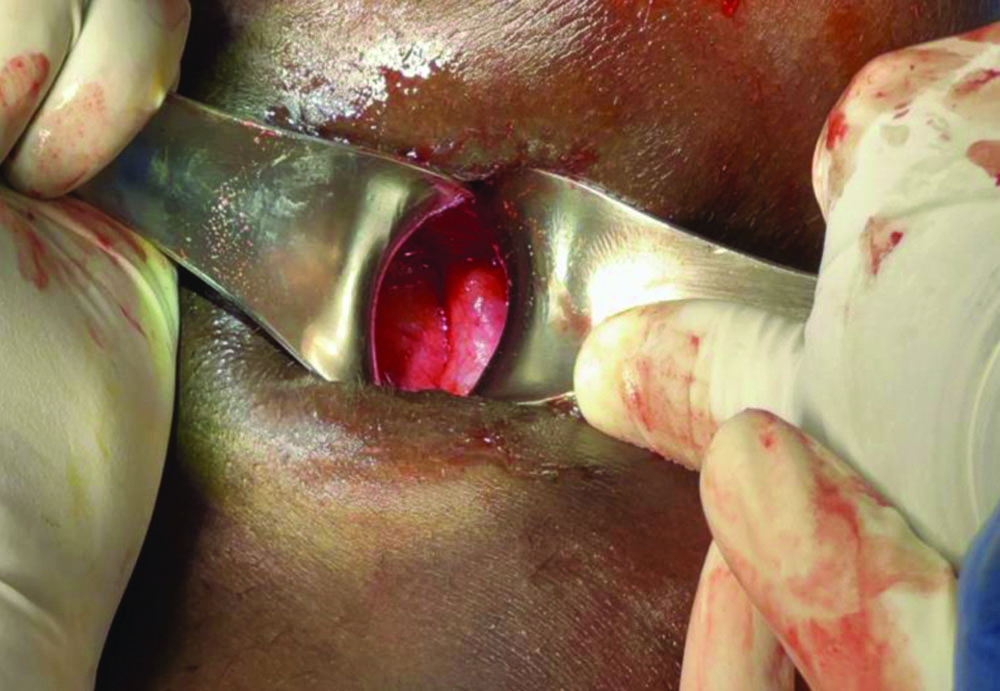

Surgical procedure: The first stage involved the creation of the neovaginal cavity. An inverted V-shaped incision was made in the vaginal dimple. Blunt and sharp dissection was carried out to create a gap between the bladder and the rectum [Table/Fig-1]. Utmost care was taken to avoid injury to the bladder and rectum. A roughly 10- to 14-cm long cavity with a 4-5 cm diameter was formed. After achieving haemostasis, the cavity was temporarily packed. The procedure’s second stage was carried out using the preoperative technique selected by the patient and the surgeon.

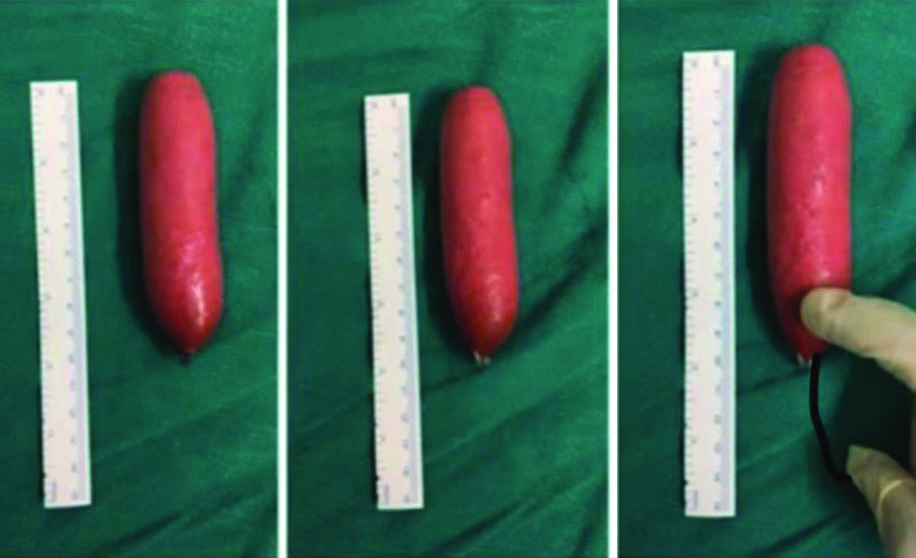

In the Abbe McIndoe technique, sheets of skin grafts were taken from the medial portion of the inner thigh, which were then positioned inside out (with the raw area visible on the exterior) over the sponge conformer [Table/Fig-2].

Graft preparation for Abbe McIndoe procedure.

The borders of the wounds and the skin graft were sutured together. A soft sponge mould was placed in the neovaginal cavity over the graft, and subsequently, the labia minora were sutured. The patient remained bedridden for five days following surgery. On the fifth postoperative day, the first look at the skin graft was performed under sedation after removing the labial sutures, and the sponge was carefully removed. Dressing was applied, and the stent was then repositioned. The second and third looks at the graft were performed on a 3-day interval. The urinary catheter was removed after the third look. Once the graft was settled and healed, the sponge mould was discontinued, and a dental compound mould was used [Table/Fig-3,4]. Patients were advised and educated on the proper direction of use of the mould daily for three months, following which the patients were permitted to have coitus.

Sponge mould for Abbe McIndoe surgery.

Creation of a solid mould.

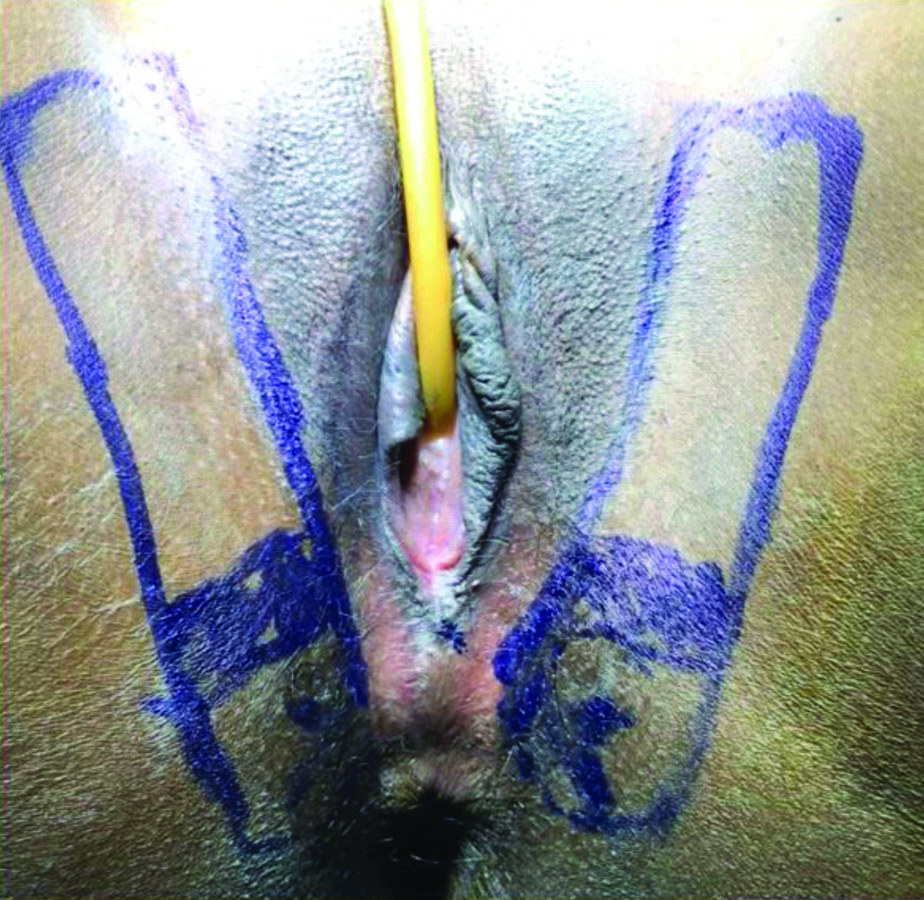

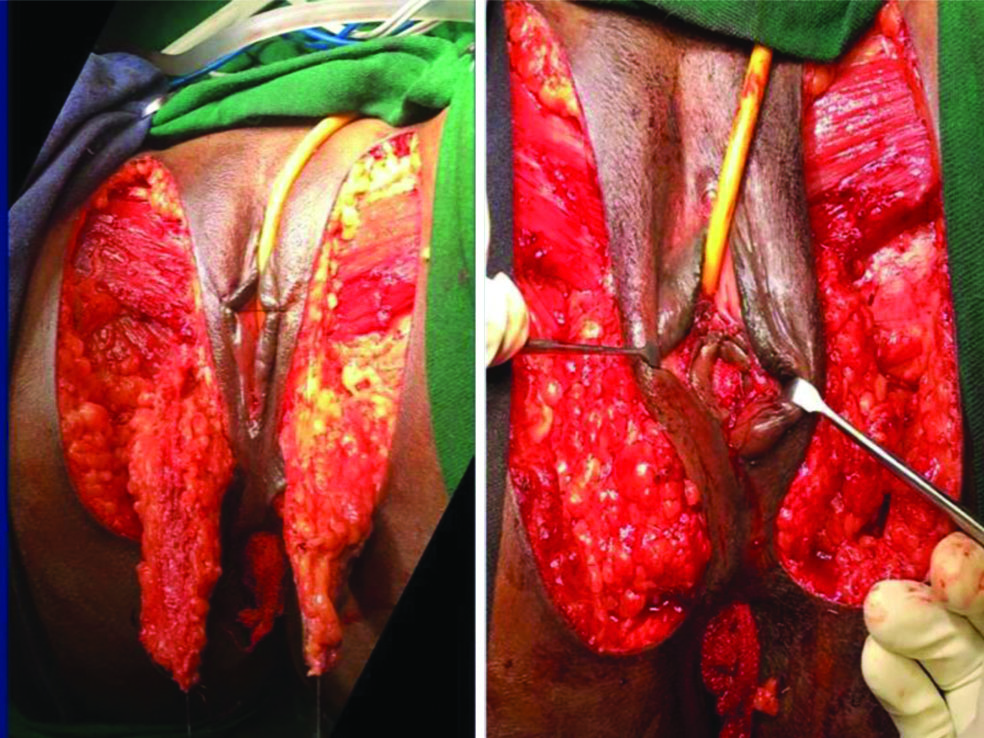

In the case of the Singapore flap, preoperative markings of the perforators were done using a handheld Doppler [Table/Fig-5]. Bilateral fasciocutaneous flaps, based on the cutaneous perforators from the pudendal artery, were harvested. The constituents of the flap included the skin, subcutaneous fat, and fascia covering the adductor muscles [Table/Fig-6].

Flap markings of Singapore flap.

Flap harvesting and inset in case of Singapore flap.

The flaps were centred medially to the thigh crease and laterally to the labia majora. They were elevated in the subfascial plane. The perforator vessels entering the base of the flaps were preserved. After elevating the flap and ensuring the perforator was entering it, the flap was islanded and rotated 90°, tunnelling under the labia minora after de-epithelialisation of the tunneled portion. The donor site was sutured in layers after flap harvesting. The rotated flap was then sutured together in a tubed fashion, and the inset was given into the neovaginal canal, with the apex of each flap being stitched to the sacrum. [Table/Fig-7] denotes the immediate postoperative appearance of both flaps. The patients were advised bed rest for the first three days with thigh adduction. Examination on the table was done on the third day for flap inspection and dressing [7]. In this group of patients, the mould was not used. The patients were advised on local hygiene and encouraged to have coitus after a month.

Immediate postoperative appearance in cases of McIndoe surgery and Singapore flap, respectively.

The participants were recalled for review for a period of one year [Table/Fig-8,9].

Long-term complication (scar hypertrophy) in Abbe McIndoe surgery.

Long-term follow-up of Singapore flap showing a patent vaginal canal.

Coitus was encouraged after ensuring full healing. Daily self-dilatation with a dental compound mould was recommended for those who were not sexually active for a maximum of six months. Postoperative care involved specific protocols based on the surgical technique, with follow-up conducted for one year. The parameters studied included quantitative measures such as age, neovaginal length, operative time, and hospital stay, along with qualitative measures such as sexual satisfaction, mould use compliance, and donor site morbidity.

Statistical Analysis

The collected data were analysed using SPSS version 26.0. Continuous variables were expressed as mean±standard deviation, while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Statistical comparisons between the two groups were made using the Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

[Table/Fig-10] compares key patient demographics and surgical metrics between the Singapore flap and Abbe McIndoe procedure groups. Both groups had a similar mean±SD age of 22.6±4.16 years, indicating comparable age distribution among participants. The mean±SD operative time was slightly longer for the Singapore flap (127±8.37 minutes) compared to the Abbe McIndoe procedure (123±13.03 minutes). Hospital stay was more extended for the Singapore flap group (11.17±1.32 days) than the Abbe McIndoe procedure group (9.17±1.94 days), suggesting a potentially more extended recovery period. The mean±SD neovaginal length achieved was slightly more significant in the Singapore flap group (9.28±0.25 cm) than in the Abbe McIndoe procedure group (8.88±0.61 cm), indicating a marginally better anatomical outcome.

Patient demographics and surgical metrics.

| Parameters | Singapore flap (n=6) | Abbe McIndoe procedure (n=6) | p-value |

|---|

| Age in years (Mean±SD) | 22.6±4.16 | 22.6±4.16 | 1.000 |

| Operative time (minutes) (Mean±SD) | 127±8.37 | 123±13.03 | 0.544 |

| Hospital stay (days) (Mean±SD) | 11.17±1.32 | 9.17±1.94 | 0.067 |

| Neovaginal length (cm) (Mean±SD) | 9.28±0.25 | 8.88±0.61 | 0.183 |

Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis of continuous variables (Age, operative time, hospital stay, neovaginal length)

The Singapore flap group had no late complications, and only 1 (16.66%) immediate complication-wound dehiscence, indicating a favourable outcome for this technique. In contrast, the Abbe McIndoe procedure group had 2 (33.33%) late complications including vaginal stenosis and scar hypertrophy and 2 (33.33%) immediate complications-graft loss and infection, suggesting a higher risk of complications with this procedure. The absence of late complications in the Singapore flap group highlights its potential advantage in long-term outcomes. These findings suggest that the Singapore flap procedure may be associated with a lower risk of immediate and long-term complications than the Abbe McIndoe procedure, making it a potentially safer and more practical option for patients undergoing neovaginal reconstruction.

Mould use was not required in Singapore flap cases, indicating a more straightforward postoperative care regimen. In the Abbe McIndoe procedure group, mould use was satisfactory in 4 (66.67%) instances and non satisfactory in 2 (33.33%) cases, indicating variability in patient compliance and outcomes related to mould use. The lack of mould requirement in the Singapore flap group suggests a significant benefit in patient comfort and postoperative management.

The Singapore flap group reported no donor site morbidity in any of the cases, highlighting a clear advantage over the Abbe McIndoe procedure group, where donor site morbidity was present in 4 (66.67%) cases. This difference underscores the Singapore flap’s superior outcome in minimising postoperative complications related to the donor site, making it a more favourable option for patients.

The Singapore flap group had a higher level of sexual satisfaction, with 5 (83.33%) cases rated as ‘good’ and 1 (16.66%) as ‘satisfactory,’ with no cases rated as ‘non satisfactory.’ In the Abbe McIndoe procedure group, 1 patient was sexually inactive and in the remaining 5 patients only 3 (50%) cases rated as ‘good,’ with 2 (33.33%) cases rated as ‘non-satisfactory,’ and none as ‘satisfactory.’ These results suggest that the Singapore flap may offer better outcomes in terms of sexual satisfaction, which is a critical consideration in neovaginal reconstruction surgeries [Table/Fig-11].

| Outcome | Singapore flap (n=6) | Abbe McIndoe procedure (n=6) |

|---|

| Complications n (%) |

| Late | 0 | 2 (33.33) |

| Immediate | 1 (16.66) | 2 (33.33) |

| Mould use n (%) |

| Satisfactory | 0 | 4 (66.67) |

| Non satisfactory | 0 | 2 (33.33) |

| Donor site morbidity n (%) |

| Present | 0 | 4 (66.67) |

| Absent | 6 (100) | 2 (33.33) |

| Sexual satisfaction n (%) |

| Good | 5 (83.33) | 3 (50) |

| Satisfactory | 1 (16.67) | 0 |

| Non satisfactory | 0 | 2 (33.33) |

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that the Singapore flap technique for neovaginal reconstruction in patients with MRKH syndrome offers several advantages over the Abbe McIndoe procedure, both in terms of surgical outcomes and patient satisfaction. These findings are consistent with existing literature, further reinforcing the potential benefits of the Singapore flap in this context.

This study found that while the mean operative time for the Singapore flap was slightly longer (127±8.37 minutes) compared to the Abbe McIndoe procedure (123±13.03 minutes), both techniques achieved comparable mean neovaginal lengths, with the Singapore flap yielding a slightly better outcome (9.28±0.25 cm vs. 8.88±0.61 cm). These results aligned with those reported by Adamyan RT et al., who observed that the Singapore flap, despite its more complex surgical demands, consistently produces excellent anatomical outcomes comparable to, if not better than, other techniques [10]. A key finding from this study was the significantly lower complication rate associated with the Singapore flap. No late complications were observed, and only one immediate complication (wound dehiscence) was reported. In contrast, the Abbe McIndoe procedure group experienced a higher incidence of both immediate and late complications, including graft loss, infection, and vaginal stenosis. These results mirror the findings of Casey WJ et al., who documented higher risks of graft failure and other complications associated with the Abbe McIndoe technique, emphasising the need for careful long-term follow-up when using this procedure [11].

The absence of a requirement for postoperative mould use in the Singapore flap group was another significant advantage, as it simplifies postoperative care and enhances patient comfort. This benefit is supported by previous studies that highlight the natural anatomical fit of the Singapore flap, which reduces or eliminates the need for external moulds, unlike the Abbe McIndoe procedure, where patient compliance with mould use was variable and sometimes problematic [6]. This study also revealed a clear difference in donor site morbidity between the two techniques. The Singapore flap group reported no donor site morbidity, whereas the Abbe McIndoe group had four cases related to the donor site. This finding underscores the importance of minimising donor site complications, highlighted in the literature as a crucial factor in improving overall patient outcomes and satisfaction [7].

Sexual satisfaction, a critical measure of success in neovaginal reconstruction, was higher in the Singapore flap group, with most patients reporting excellent or satisfactory outcomes, and none reporting non satisfactory results. In contrast, the Abbe McIndoe group had a more variable distribution of sexual satisfaction, with two cases rated as non satisfactory. These results were consistent with studies by Morcel K et al., who reported that the Singapore flap provides superior outcomes in terms of sexual function due to its ability to create a sensate and functional neovagina [3]. The present study’s findings aligned with existing literature when considering success rates. The Singapore flap reported to have a success rate greater than 90%, reflecting high anatomical success rates, functional outcomes, and patient satisfaction. The Abbe McIndoe procedure, while also generally successful with a reported success rate of around 80-90%, is associated with higher complication rates that can negatively impact long-term outcomes and patient satisfaction [1,8].

Long-term outcomes are critical in evaluating the success of neovaginal reconstruction techniques such as the Singapore flap and Abbe McIndoe procedure. One of the key indicators of long-term success is the sustained patency and functionality of the neovagina, which includes the absence of complications like vaginal stenosis and the maintenance of sexual function over time. Studies have shown that patients who undergo the Singapore flap procedure tend to experience fewer long-term complications, such as stenosis or the need for repeated interventions, than those who undergo the Abbe McIndoe procedure [9].

Another critical aspect of long-term outcomes is the psychological and quality-of-life improvements associated with successful neovaginal reconstruction. Patients who report higher levels of sexual satisfaction and fewer complications generally exhibit better overall psychological well being, which underscores the importance of these factors in the long-term success of these procedures [12].

Demographic factors such as age, Body Mass Index (BMI), and overall health status can significantly influence the success rates and long-term outcomes of neovaginal reconstruction. Younger patients tend to heal faster and have fewer complications, partly due to better overall health and tissue quality. In contrast, older patients or those with co-morbid conditions such as diabetes or obesity may experience slower healing and a higher risk of complications [13]. Moreover, the psychosocial aspects of patient care, including the patient’s support system and mental health, play a crucial role in the success of the reconstruction. Patients with strong social support and good mental health are more likely to adhere to postoperative care instructions, such as regular dilation therapy, which is crucial for maintaining neovaginal patency, especially in cases where moulds are required [14].

Finally, ethnic and cultural factors may also influence patient expectations and perceptions of success. Different cultural backgrounds can lead to varying levels of satisfaction with the surgical outcomes, particularly regarding the importance placed on sexual function and body image [15]. The long-term consequences of neovaginal reconstruction procedures like the Singapore flap and Abbe McIndoe procedure are influenced by the surgical technique and demographic factors such as age, health status, and cultural background. Understanding these factors can help tailor patient care to maximise the success and satisfaction of surgical outcomes.

This study and comparative studies in the literature support the growing evidence that the Singapore flap technique may offer superior outcomes compared to the Abbe McIndoe procedure in neovaginal reconstruction for MRKH syndrome. The lower complication rates, reduced need for postoperative interventions, absence of donor site morbidity, higher levels of sexual satisfaction, and higher reported success rates all suggest that the Singapore flap should be considered a preferred technique in appropriate clinical settings. Future studies with larger sample sizes and extended follow-up periods would be valuable to further confirm these findings and optimise the surgical approach.

Limitation(s)

This study had some limitations that need to be acknowledged. The small sample size of only 12 patients limits the generalisability of the findings, and the single-centre nature of the study may not reflect outcomes in other clinical settings. The short follow-up period of one year may not capture long-term complications or the durability of surgical outcomes. Additionally, patient and surgeon preferences may have influenced the randomisation, potentially introducing bias. The focus on a limited set of parameters, particularly the subjective assessment of sexual satisfaction, without including broader quality of life measures, further limits the study’s comprehensiveness. Lastly, the findings are specific to MRKH syndrome, making it unclear whether they can be applied to patients with vaginal defects from other causes.

Conclusion(s)

The Singapore flap has been observed to be relatively superior to the Abbe McIndoe procedure in terms of not requiring a mould, having no donor site morbidity, improving sexual satisfaction, and enhancing patient compliance. It is an efficient method for vaginal reconstruction, and most of the time, there are no issues. Neovaginal cavities created through the Singapore flap exhibit characteristics comparable to those of normal female anatomy, including sufficient depth and width, the correct angle of inclination, no permanent need for dilatation, sensitivity, and no risk of prolapse.

Student’s t-test was used for statistical analysis of continuous variables (Age, operative time, hospital stay, neovaginal length)