Inhaling crystalline silica dust is the primary cause of silicosis, a progressive and crippling occupational lung disease that mostly affects those working in the manufacturing, construction, and mining sectors. Exposure to silica causes a series of inflammatory reactions in the lungs, resulting in the deposition of fibrous tissue and irreparable harm to the respiratory system. Silicosis is presently the most common chronic occupational illness in the world, and the burden of silica-associated diseases is significant [1].

Considering its propensity to result in physical impairment, silicosis remains one of the world’s most significant occupational health disorders. In India, the incidence of silicosis varies greatly, it can vary from 3.5% in ordnance factories to 54.6% in the slate-pencil sector [2], but only few epidemiological studies have been done so far on this disease [3]. Increasing age, the duration of exposure to dust, smoking status, and the existence of chronic obstructive lung disease are all strongly correlated with the severity of pulmonary function impairment in radiological analyses [4]. Patients suffering from pulmonary fibrosis due to chronic silica dust exposure typically experience profound respiratory impairment, leading to reduced lung function, higher pulmonary resistance, and decreased perfusion capacity [5]. Regular assessment of lung functions would serve as a basis for identifying lung abnormalities in the early stages of the disease, as deterioration in pulmonary function typically becomes apparent only in the later stages when a significant portion of lung tissue has been destroyed [6]. Preventing and controlling this fatal but avoidable disease is plagued with challenges, including an uncontrolled informal sector, diagnostic hurdles, lack of monitoring, insufficient personnel, and low awareness [7].

Spirometry is a method for evaluating lung function that involves measuring the amount of air an individual can evacuate from the lungs following a maximum inspiration [8]. Pulmonary function tests have ushered in a new era of scientific approaches to the diagnosis, prognosis, and management of pulmonary disorders by enabling the early detection of changes in pneumoconiosis workers who are constantly exposed to silica dust, as well as the implementation of protective and preventive measures to reduce the hazards of exposure to polluted environments [9]. There are several stone quarries and mining businesses in the western region of Bengal; however, compared to the rest of India, very few research has been done among these workers. This lack of research may make it more difficult to identify and prevent lung damage in these workers in the early stages. Silicosis is a significant issue in West Bengal, particularly among stone-crushing and quarrying workers in the Birbhum area. The “West Bengal Silicosis Control Programme” was designed as a state effort in July 2012 and was piloted in Birbhum, West Bengal, India [10].

The primary objective of this study was to determine the alterations in pulmonary function status (by spirometry) and to evaluate the gender differences in pulmonary mechanics among occupationally silica dust-affected workers.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted at the Department of Physiology, Rampurhat Government Medical College, West Bengal, India, from April to June 2024. Institutional Ethical Clearance (IEC) was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of Rampurhat Government Medical College (Memo No. RPHGMCH/STAC/67 dated 01.03.2024).

Inclusion criteria: Clinically stable patients, including males and females aged 30-60 years, with history of working in stone crusher units for more than five years and have been exposed to occupational silica dust, and who attended the Department of Physiology after being referred from the Pulmonology Department for spirometric evaluation of their lung function were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with acute Lower Respiratory Symptoms (LRS), patients attending for preanaesthetic check-ups, patients suspected of having active pulmonary tuberculosis, those with haemoptysis, patients with known cardiovascular, subdiaphragmatic or otorhinolaryngological diseases and female patients having active menstrual bleeding were excluded from the study.

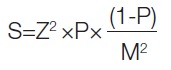

Sample size calculation:

Calculated using the formula:

Where,

S=sample size

Z=Z score (here 1.960 based on a confidence level of 95%)

P=population proportion (here 0.2, taking the prevalence of silicosis to be 20%) [11]

M=margin of error (10%)

So, the sample size comes to 62.

Study Procedure

Anthropometric measurements of the patients, including weight and height, were measured using a weighing machine and a stadiometer, respectively. Furthermore, BMI was calculated using the weight and height values:

BMI=Weight (in kg)/Height2 (in meters) [12].

The patients were clearly instructed regarding the spirometric technique. The room temperature was set at 27°C, and the patients were seated during the procedure.

Spirometry was performed using an electronic spirometer (RMS HELIOS 702) that was preprogrammed with the current recommendations from the ATS and the ERS (2005), with an 80% ethnic adjustment. Before the procedure, the spirometer was thoroughly checked for any damage or leakage. During the research, the spirometer was calibrated daily using a calibrated syringe, following the most recent ATS/ERS recommendations [13].

The largest observed values of FEV1 and FVC obtained from at least three acceptable and reproducible tests were considered during the final interpretation of the results.

The normal limits of the data are taken as follows: FVC (80-120%) [14], FEV1 (80-120%) [14], PEFR (>60% predicted value for men, with readings up to 100 L/min lower than predicted; for women, the equivalent figure is 85 L/min) [15], FEF25-75% (50%-60% and up to 130% of the average) [16], FET (6 seconds) [17], and FEV1/FVC ratio (70-85%) [18].

After the completion of spirometry, all the patients were categorised as per existing standard criteria based on FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, FEF25%-75%, and PEFR values, with interpretation of RSP and SAO done based on the aforementioned reference limits:

Normal [14,18];

Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (including mild/moderate/severe/very severe): FEV1/FVC <70% and FEV1 value <100% of predicted [19];

Restrictive Spirometric Pattern (RSP): FVC <80%, FEV1 ≤80% (normal/decreased), and FEV1/FVC ≥0.7 (normal/increased) [19];

Mixed Ventilatory Defect: FEV1/FVC <0.7 and FVC <80% of predicted [20];

Small Airflow Obstruction (SAO): FEF25%-75% <50% of predicted [21,22].

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Chi-square test with Microsoft Excel and GraphPad QuickCalcs software, California, USA. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Furthermore, gender variance analysis was evaluated using the Unpaired t-test.

Results

FET was noted to be significantly higher in male subjects. The BMI of the study population was observed to be 17.337±2.482 for males and 16.949±2.691 for females, which falls under the underweight category. Furthermore, the spirometric values were observed to be lower than the Lower Limit of Normal (LLN), except for the FEV1/FVC ratio, which was higher (105.27±11.69 in males and 112.73±9.12 in females) [Table/Fig-1].

Gender variance analysis of the study population.

| Variables | Males (n=51) | Females (n=11) | t value | p-value |

|---|

| Age (years) (Mean±SD) | 49.47±9.25 | 50.18±9.84 | 0.228 | 0.819 |

| BMI (kg/mt2) (Mean±SD) | 17.337±2.482 | 16.949±2.691 | 0.462 | 0.645 |

| FVC (%pred.) (Mean±SD) | 53.27±23.03 | 57.64±27.08 | 0.552 | 0.582 |

| FEV1 (%pred.) (Mean±SD) | 56.25±25.97 | 65.0±31.26 | 0.977 | 0.332 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio (%pred.) (Mean±SD) | 105.27±11.69 | 112.73±9.12 | 1.984 | 0.051 |

| PEFR (%pred.) (Mean±SD) | 44.78±26.06 | 52.36±27.85 | 13.106 | 0.39 |

| FEF25%-75% (%pred.) (Mean±SD) | 56.02±40.03 | 61.0±35.64 | 0.380 | 0.704 |

| FET (Sec) (Mean±SD) | 2.182±1.507 | 1.152±0.554 | 2.221 | 0.030* |

BMI: Body mass index; FVC: Forced vital capacity; FEV: Forced expiratory volume; PEFR: Peak expiratory flow rate; FEF: Forced expiratory flow; FET: Forced expiratory time

It was observed that the majority of these subjects belonged to the mixed ventilatory defects (RSP+SAO) (58.06%) and RSP (27.42%) categories [Table/Fig-2].

Overall categories of subjects based on spirometric interpretation.

| Spiromteric interpretation | n (%) |

|---|

| Restrictive Spirometric Pattern (RSP) | 17 (27.42) |

| RSP+Small Airflow Obstruction (SAO) | 36 (58.06) |

| Normal | 9 (14.52) |

Most of the study subjects were males (82.26%) and that the percentage of smokers was predominantly males (58.06%) [Table/Fig-3a].

Gender variation and smoking habits of the study population.

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|

| Males | 51 (82.26) |

| Females | 11 (17.74) |

| Smokers | 36 (58.06) |

| Non smokers | 26 (41.94) |

Chi-square analysis without Yates correction was conducted. The Chi-squared value equals 18.516 with 1 degree of freedom. The association between rows (gender variance) and columns (smoking habits) is statistically extremely significant, which shows predominance of smokers among males [Table/Fig-3b].

Qualitative analysis between the genders regarding the smoking habits.

| Gender | Smokers (n=36) | Non smokers (n=26) | p-value (two-tailed) |

|---|

| Males | 36 | 15 | <0.0001 |

| Females | 0 | 11 |

It was observed that there was no significant difference between the spirometric patterns of RSP, RSP+SAO and normal patterns between smokers and non smokers [Table/Fig-4].

Categorisation of spirometric patterns in smokers and non-smokers.

| Spirometric interpretation | Smokers | Non smokers | p-value |

|---|

| RSP | 8 (22.22%) | 9 (34.61%) | 0.533 |

| RSP+SAO | 22 (61.11%) | 14 (53.84%) |

| Normal | 6 (16.67%) | 3 (11.55%) |

Chi-square test equals 1.256 with 1 degrees of freedom

The association between RSP+SAO and normal pattern in smokers and non smokers was statistically not significant. The association between RSP and Normal pattern in smokers and non smokers was statistically not significant. The association between RSP+SAO and RSP pattern in smokers and non smokers was statistically not significant [Table/Fig-5].

Qualitative comparison of study findings among smokers and non-smokers.

| a | RSP+SAO | Normal | Total | p-value (two tailed) |

|---|

| Smokers | 22 | 6 | 28 | 0.7585 |

| Non smokers | 14 | 3 | 17 |

| Total | 36 | 9 | 45 |

| Chi-square equals 0.095 with 1 degrees of freedom |

| b | RSP | Normal | Total | p-value (two tailed) |

| Smokers | 8 | 6 | 14 | 0.340 |

| Non smokers | 9 | 3 | 12 |

| Total | 17 | 9 | 26 |

| Chi-square equals 0.910 with 1 degrees of freedom |

| c | RSP+SAO | RSP | Total | p-value (two tailed) |

| Smokers | 22 | 8 | 30 | 0.3353 |

| Non smokers | 14 | 9 | 23 |

| Total | 36 | 17 | 53 |

| Chi-square equals 0.928 with 1 degrees of freedom |

Discussion

The present study focuses on the various respiratory involvement patterns in individuals who have been exposed to occupational silica dust. The spirometric values in the present study, including FVC, FEV1, PEFR, FEF25-75, and FET, were all below the lower normal limits for percent predicted as well as absolute values, except for the FEV1/FVC ratio, which was higher than the normal limits. Similar findings were obtained in a study by Wardyn PM et al., which reported that exposure to crystalline silica dust significantly affected respiratory function, resulting in bronchial and small airway blockage and the prevalence of compromised FEV1/FVC and FEF25-75 increased with cumulative silica exposure for three years or more [23]. The reduction in lung function can be affected by the duration of exposure to occupational silica dust, as several studies have shown a progressive deterioration of lung function parameters with an increase in the duration of exposure, particularly in those exposed for more than 10 years [24-26].

Another significant finding of the present study was that the majority of the study population were in underweight category. The poor nutritional status of the silicotic patients, which was evident by their underweight status, is corroborated by numerous studies, including one by Chowdhury N et al., among agate workers in Gujarat, and another by Madahaban P and Raj S in Rajasthan [27,28]. The study by Chowdhury N et al., also reported that malnutrition is linked to higher fatality rates in silicosis sufferers [27]. A study among pneumoconiosis patients by Peng Y et al., reported a higher incidence of obstructive disease among underweight age groups [29]. In sharp contrast to the results mentioned above, one study found that the majority of silicotic patients were overweight and obese [30], while one study found no significant correlation between the weight of the patients and silicotic severity of silicosis [31].

The findings of the current study indicate that the majority of the participants had RSP and that many of them had mixed ventilatory abnormalities. Similar data were obtained by a study conducted on 85 female quartz workers by Tiwari RR and Sharma YK which showed that exposure to free silica dust caused obstructive, restrictive, and combined (both obstructive and restrictive) patterns in lung function on spirometry, and that respiratory morbidity was strongly associated with the duration of exposure [32]. Individuals with advanced simple silicosis (International Labour Organisation Category 3) were more likely to have a restrictive abnormal pattern on spirometry, whereas those with progressive massive fibrosis were more likely to have both obstructive and restrictive findings on spirometric tests [33].

A plausible explanation for the elevated occurrence of mixed defects in silicotics might be the involvement of the airways due to pulmonary fibrosis [34]. Silicosis involves the interaction between silica particles and alveolar macrophages, leading to an inflammatory cascade and subsequent pulmonary fibrosis [1]. Pulmonary fibrosis is not only a clinical cause of restrictive lung abnormalities in fibrotic lung illnesses such as silicosis, but it can also result in airway distortion, which can induce airway obstruction [35]. The restrictive or mixed pattern in spirometry seen in advanced cases of silicosis [36] carries an overall higher risk of mortality compared to normal persons as shown in a study by Yang S et al., and hence calls for early diagnosis and intervention in such cases [34].

Male predominance concerning susceptibility to silicosis and smoking habits is evident from the results of the present research, which was similar to the findings of studies by Rajavel S et al., among workers in sandstone mines in Rajasthan [2] and by Tiwari RR et al., among quartz stone ex-workers in Gujarat [6]. Although differences in respiratory involvement may not be significantly different between male and female counterparts, gender bias may lead to delayed diagnosis in female workers, as shown in a study by Kerget B et al., [37].

The restrictive, obstructive, or mixed patterns of lung pathologies were not found to be statistically significant between smokers and non smokers in the current study. There is ongoing debate regarding smoking’s relationship to silicosis. In past research, smoking was thought to be a risk factor for silicosis [38]; however, other investigations found no meaningful correlation between smoking status and silicosis [39]. Smoking can indeed affect lung function parameters like Diffusing Capacity for Carbon Monoxide (DLCO) and increase FET, as shown in the study by Sill J [40]. On the other hand, in smokers, there was a statistically significant correlation between the amount of emphysema and silica dust, indicating that smoking tobacco increases silica dust’s possibly hazardous effects of silica dust [41].

In this study, the authors found that notable changes in lung parameters occur in individuals exposed to silica dust for prolonged periods, which can be easily diagnosed by simple spirometry. So, special emphasis is to be given on the detection of lung damage so that early precautionary measures can be taken in workers of stone quarries, whose health is generally neglected.

Limitation(s)

There are few limitations of the present study that need to be considered:

1) The patients’ clinical profiles, including histories of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking, and the use of bronchodilators, steroids, and antihistamines, were not obtained, which could be a potential source of confounding factors.

2) Smoking has been observed to be a confounding factor in the present study.

3) Studies with a larger population and variable durations of exposure is needed to expand the validity of the findings.

4) Gender wise homogeneity among the study population was not maintained.

5) Apart from doing the spirometric study, no other tests have been conducted to establish restrictive lung disease among stone quarry workers.

Conclusion(s)

Detectable spirometric changes have been observed among stone quarry workers, where not only restrictive patterns but also mixed ventilatory defects were seen. Necessary preventive and interventional measures should be taken at an early phase to prevent further progression of lung impairment in such population.

BMI: Body mass index; FVC: Forced vital capacity; FEV: Forced expiratory volume; PEFR: Peak expiratory flow rate; FEF: Forced expiratory flow; FET: Forced expiratory time

Chi-square test equals 1.256 with 1 degrees of freedom