Facial angiofibromas (FAs) are a distressing manifestation of Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC), often leading to significant physical and psychological burdens. Traditional treatment modalities have limitations, prompting the exploration of alternative therapies. In the present case series, topical sirolimus, a Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, was used to manage FAs associated with TSC. Four cases (1 male and 3 female) of FAs in patients with TSC were treated with 0.1% sirolimus ointment applied once daily. The Facial Angiofibroma Severity Index (FASI) was utilised to assess FA severity at baseline and during follow-up visits, which spanned 3 to 12 months. Patient satisfaction and tolerability were also evaluated. Results demonstrated a consistent reduction in FASI scores across all patients, indicating improved FA severity. Patient satisfaction varied, with higher contentment observed in cases where treatment was initiated at a younger age. Importantly, no significant adverse effects were noted, affirming the safety profile of topical sirolimus. These findings underscore the potential of topical sirolimus as a promising therapeutic avenue for FAs in TSC, offering a cost-effective and well-tolerated alternative to conventional treatments. Further research is warranted to elucidate optimal dosing strategies and long-term outcomes, but current evidence supports its consideration as a viable option in the management of FAs associated with TSC.

Introduction

The neurocutaneous condition known as Tuberous Sclerosis Complex (TSC) is an autosomal dominant multisystem disorder caused by mutations in the tumour suppressor genes TSC1 and TSC2. TSC1 is located at gene locus 9q34.3 and codes for the hamartin protein, while TSC2 is located at 16p13.3 and codes for the tuberin protein [1]. Facial Angiofibromas (FA) are the most predominant cutaneous manifestation of TSC, occurring in approximately 75% to 90% of patients [2]. The overall incidence of TSC varies between 1/10000 and 1/100000 [3].

The FA consists of multiple small, pinkish, erythematous hamartomas, typically appearing between the ages of two and five and worsening with age. These lesions are associated with spontaneous bleeding, pain, risk of infection, facial disfigurement and impairment of patient functions such as vision and breathing, which can ultimately diminish the patient’s quality of life [4]. Jansen AC et al., found that FA significantly impacts individuals and their families, with nearly half experiencing setbacks in education or career. The condition affects family, social and work life, with limited access to coordinated care and moderate rates of pain, discomfort, anxiety and depression among patients [5].

At present, available treatment options are limited to cryosurgery, dermabrasion, photodynamic therapy, laser therapy and surgery. These approaches have not demonstrated sustained efficacy and accessibility in the long-term and often involve complications [6]. Less invasive topical treatment with mTOR inhibitors has been advocated and its safety and efficacy for this purpose have been demonstrated in clinical trials [7]. The mTOR inhibitors mimic the functions of the TSC gene products by blocking mTOR activity. Both sirolimus and everolimus, a 40-O-(2-hydroxyethyl) derivative, efficiently block mTOR [8,9]. However, concerns about systemic adverse effects limit the use of sirolimus ointment for treating FA. In India, sirolimus is available in 1 mg and 2 mg tablets. These tablets can be powdered and combined with a desired ointment, cream, or gel base to create a topical preparation.

Case studies have reported various formulations, production methods and dosages, but only a few have evaluated rash intensity or treatment response with a scoring method [7,10,11].

The present series highlights our experience using 0.1% sirolimus ointment in four cases of FA and aims to determine its efficacy using the standardised and validated Facial Angiofibroma Severity Index (FASI).

Case Series

The four respondents, consisting of one male and three females aged between five and 19 years, were diagnosed to have TSC based on the criteria established by the International TSC Consensus Conference in 2012 [12] and they all had associated FA diagnosed clinically. Each patient was instructed to apply a thin layer of 0.1% sirolimus ointment to the skin lesions once in the evening, ensuring to avoid any areas of open skin. The ointment was prepared by combining 10 1 mg tablets of crushed sirolimus with 10 grams of white soft paraffin and was stored in an airtight container. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients or their guardians and baseline clinical photographs and FASI were done. They were reviewed every three months for clinical improvement and the presence of side-effects. The FASI score was calculated based on the criteria given in [Table/Fig-1] [6].

| Erythema | Size | Extension |

|---|

| Skin colour-0 | Small (<5 mm)-1 | <50% cheek surface-2 |

| Light red-1 | Large (>=5)-2 | >=50% cheek surface-3 |

| Red-2 | Confluent-3 | |

| Dark red/purple-3 | | |

FASI Score (sum of the above); Mild-<=5; Moderate-6-7; Severe- ≥8

Physician Global Assessment (PGA) was used to see the treatment response, as outlined in [Table/Fig-2] [13]. Overall patient satisfaction was assessed using a 5-point Likert scale, detailed in [Table/Fig-3]. One patient has completed 12 months of treatment, while the others have completed three months at the time of reporting. Improvements in the PGA and Likert scale, as well as any adverse events, were recorded.

Physician global assessment [13].

| Score | Interpretation |

|---|

| +4 | Marked improvement |

| +3 | Much improvement |

| +2 | Improved |

| +1 | Slight improvement |

| 0 | No change |

| -1 | Slightly worse |

| -2 | Worse |

| -3 | Much worse |

| -4 | Marked worse |

| Score | Interpretation |

|---|

| 1 | Poor satisfaction |

| 2 | Poor satisfaction |

| 3 | Average satisfaction |

| 4 | High satisfaction |

| 5 | High satisfaction |

Case 1

A 19-year-old male presented with the onset of FA at the age of 3 years. His baseline FASI was eight, which dropped to six after 12 months of treatment [Table/Fig-4].

Clinical photographs of lesions at baseline (left) and the end of 12-month (right) treatment showing improvement in erythema and size.

Case 2

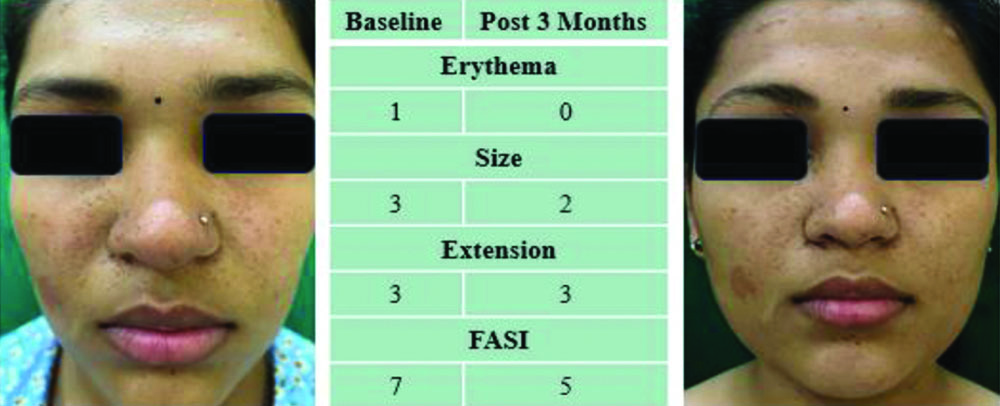

A 19-year-old female presented with FA since the age of 2 years. She had a baseline FASI of seven, which decreased to five at the end of three months [Table/Fig-5].

Clinical photographs of lesions at baseline (left) and after 3-month (right) treatment showing no improvement.

Case 3

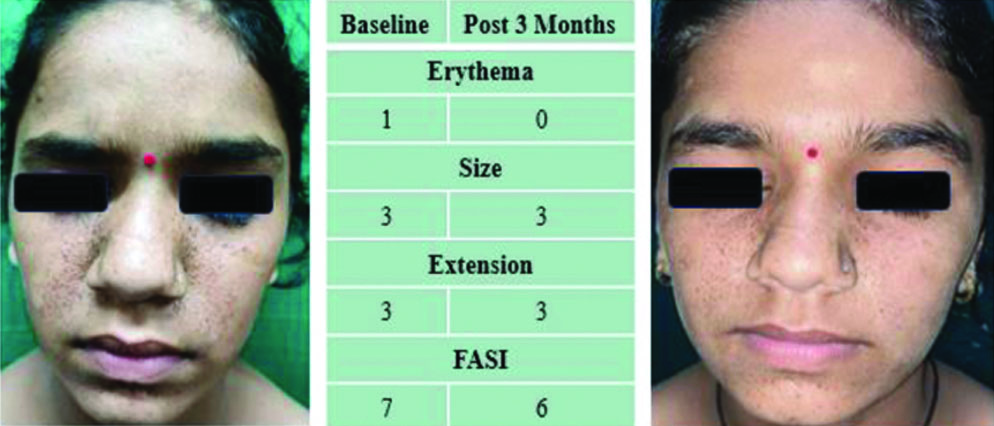

A 14-year-old girl presented with FA since she was four years old. She had a baseline FASI of seven, which reduced to six after three months of treatment [Table/Fig-6].

Lesions at baseline (left) and post-3-month (right) treatment showing size reduction.

Case 4

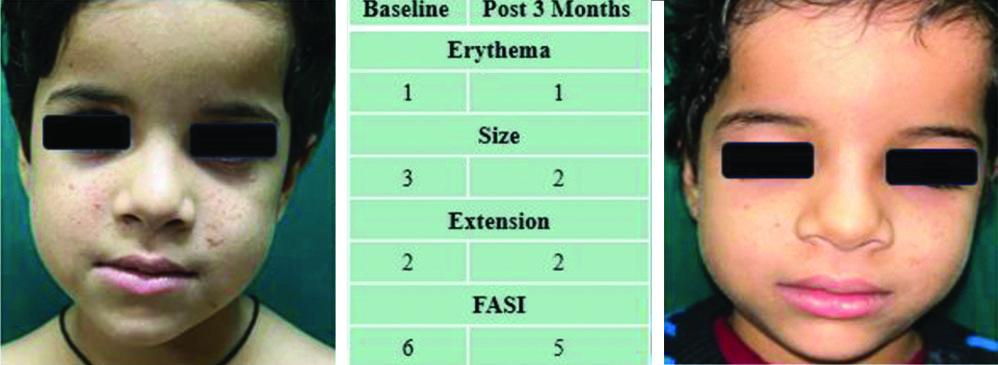

A 5-year-old girl had FA since the age of 3 years old. Her baseline FASI was six, which decreased to five in three months [Table/Fig-7].

Lesions at baseline (left) and post-3-month (right) treatment showing improvement in size.

The improvements on PGA and the Likert scale, as well as the adverse events in each case, are tabulated in [Table/Fig-8].

Summary of baseline characteristics and clinical improvement based on PGA, Likert scale and adverse events.

| Case no. | Age/sex | Physician global assessment | Overall treatment satisfaction score (Likert) | Reported adverse events |

|---|

| 1 | 19 years/M | +3 | 4 | Nil |

| 2 | 19 years/F | +2 | 3 | Nil |

| 3 | 14 years/F | +2 | 2 | Nil |

| 4 | 5 years/F | +5 | 4 | Nil |

Discussion

The TSC is characterised by the development of hamartomas affecting multiple organ systems. In individuals with TSC, the mTOR pathway is hyperactive in dermal fibroblast-like cells, prompting epiregulin production and excessive epidermal cell proliferation. This, along with increased angiogenesis, drives FA development [14]. Sirolimus is a lipophilic lactone isolated from Streptomyces hygroscopicus; it inhibits mTOR, curtailing cell growth, suggesting a potential treatment avenue [9]. Sirolimus has been proven to be an effective mTOR inhibitor for FAs linked to TSC [7-10].

The authors experience with 0.1% sirolimus ointment was concordant with a Turkish case series comprising 12 children, which reported significant improvement in erythema and reduction in tumour size. The change in average FASI score was significantly different after treatment [15].

It is hypothesised that early-stage growing tumours, which have a higher proliferative component, may respond better to sirolimus. Hence, it could be more beneficial when instituted at an early age [13]. In the present case series, case 4 was started on treatment at five years of age, case 3 at 14 years and the other two at 19 years of age. Noticeable improvement was recorded in all the cases, but patient satisfaction was highest in case 4. Thus, topical sirolimus may have benefits at any age of presentation, but the best results may be seen when treatment is started early.

Wataya-Kaneda M et al., reported the effects of different topical concentrations of sirolimus on angiofibromas for varying durations and concluded that the optimal concentration of sirolimus was 0.2% [7]. Since there is no clear endpoint for topical sirolimus in FA and prolonged treatment is the norm-and considering the lower socio-economic status of the patients, the authors finalised 0.1% topical ointment for our patients due to its greater cost-effectiveness and compliance.

Although the present case series did not study the quality of life, the authors assessed overall satisfaction related to the treatment, wherein the participants (or their parents) were asked to consider the cosmetic as well as mental satisfaction while scoring the treatment. All the cases tolerated the application well and experienced no side-effects.

The findings of the present case series cannot be generalised due to several limitations. First, the study lacked randomisation, which may introduce bias. Second, the small sample size limits the reliability of the results. Additionally, the short follow-up period makes it difficult to assess the long-term effectiveness and safety of sirolimus ointment. Furthermore, the formulation used in the present study was manually prepared, which may lead to inconsistencies in concentration and potency, potentially affecting treatment outcomes. To validate these results, larger randomised controlled trials with standardised formulations and longer follow-up periods are needed.

Conclusion(s)

Topical 0.1% sirolimus ointment appears to be a promising treatment for FA in individuals with TSC, particularly in resource-limited settings where affordability is crucial. The treatment was well-tolerated, with no reported side-effects and resulted in a significant improvement in FASI scores.

FASI Score (sum of the above); Mild-<=5; Moderate-6-7; Severe- ≥8

[1]. Hatano T, Ohno Y, Imai Y, Moritake J, Endo K, Tamari M, Improved health-related quality of life in patients treated with topical sirolimus for facial angiofibroma associated with tuberous sclerosis complexOrphanet J Rare Dis 2020 15(1):13310.1186/s13023-020-01417-532487130 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Van Slegtenhorst M, de Hoogt R, Hermans C, Nellist M, Janssen B, Verhoef S, Identification of the tuberous sclerosis gene TSC1 on chromosome 9q34Science 1997 277(5327):805-08.10.1126/science.277.5327.8059242607 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Araujo LJ, Lima LS, Alveranga TM, Martelli-Júnior H, Coletta RD, de Aquino SN, Oral and neurocutaneous phenotypes of familial tuberous sclerosisOral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011 111:87-94.10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.07.00221055980 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Tee AR, Manning BD, Roux PP, Cantley LC, Blenis J, Tuberous sclerosis complex gene products, Tuberin and Hamartin, control mTOR signaling by acting as a GTPase-activating protein complex toward RhebCurr Biol 2003 13(15):1259-68.10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00506-212906785 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5]. Jansen AC, Vanclooster S, de Vries PJ, Fladrowski C, Beaure d’Augères G, Carter T, Burden of illness and quality of life in tuberous sclerosis complex: Findings from the TOSCA studyFront Neurol 2020 11:90410.3389/fneur.2020.0090432982929 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Salido R, Garnacho-Saucedo G, Cuevas-Asencio I, Ruano J, Galán-Gutierrez M, Vélez A, Sustained clinical effectiveness and favorable safety profile of topical sirolimus for tuberous sclerosis-associated facial angiofibromaJ Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012 26(10):1315-18.10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04212.x21834948 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Wataya-Kaneda M, Nagai H, Ohno Y, Yokozeki H, Fujita Y, Niizeki H, Safety and efficacy of the sirolimus gel for TSC patients with facial skin lesions in a long-term, open-label, extension, uncontrolled clinical trialDermatol Ther 2020 10:635-50.10.1007/s13555-020-00387-732385845 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Amin S, Lux A, Khan A, O’Callaghan F, Sirolimus ointment for facial angiofibromas in individuals with tuberous sclerosis complexInt Sch Res Not 2017 2017:840437810.1155/2017/840437829270462 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Koenig MK, Hebert AA, Roberson J, Samuels J, Slopis J, Woerner A, Topical rapamycin therapy to alleviate the cutaneous manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex: A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of topically applied rapamycinDrugs R D 2012 12(3):121-26.10.2165/11634580-000000000-0000022934754 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Foster RS, Bint LJ, Halbert AR, Topical 0.1% rapamycin for angiofibromas in paediatric patients with tuberous sclerosis: A pilot study of four patientsAustralas J Dermatol 2012 53(1):52-56.10.1111/j.1440-0960.2011.00837.x22309333 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. Dao DPD, Pixley JN, Akkurt ZM, Feldman SR, A review of topical sirolimus for the treatment of facial angiofibromas in tuberous sclerosis complexAnn Pharmacother 2024 58(4):428-33.10.1177/1060028023118242137386842 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[12]. Krueger DA, Northrup H, Group ITSCC, Tuberous sclerosis complex surveillance and management: Recommendations of the 2012 international tuberous sclerosis complex consensus conferencePediatr Neurol 2013 49:255-65.10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.00224053983 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13]. Assesschild. (n.d.). Assesschild.com. Retrieved June 9, 2024. Available from: https://assesschild.com/physician-global-assessment [Google Scholar]

[14]. Li S, Takeuchi F, Wang J, Darling TN, Mesenchymal-epithelial interactions involving epiregulin in tuberous sclerosis complex hamartomasProc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008 105(9):3539-44.10.1073/pnas.071239710518292222 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[15]. Cinar SL, Kartal D, Bayram AK, Canpolat M, Borlu M, Ferahbas A, Topical Sirolimus for the treatment of angiofibroma’s in tuberous sclerosisIndian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017 83:27-32.10.4103/0378-6323.19084427643542 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]