Formic acid poisoning, although uncommon, carries a high-risk of morbidity and mortality. Five cases (one male and four females) of formic acid poisoning were referred to the Emergency Department within a time frame of 60-120 minutes after ingestion. The age range was between 14 years and 70 years. Three patients had accidental ingestion, while two had ingested the substance with suicidal intent. The quantity ingested ranged from 15-30 mL of undiluted acid. Out of the five patients, two had hypertension, one had both hypertension and diabetes mellitus, and the remaining two did not have any co-morbidities. All five patients presented with orofacial burns, upper abdominal discomfort and dysphagia. One patient experienced mild haematemesis, while another had severe haematemesis. Three patients had altered sensorium due to metabolic acidosis. Four patients developed dark, cola-coloured urine and one had gross haematuria. All patients exhibited acute renal toxicity and dyselectrolytemia. Metabolic acidosis was corrected in two patients with a 7.5% NaHCO3 infusion. Four patients improved with haemodialysis and other supportive measures and were discharged within 10-16 days of admission. However, a 60-year-old patient who had gross haematuria and severe haematemesis following the accidental ingestion of 30 mL of acid expired due to severe metabolic acidosis and hypovolemic shock within eight hours of hospital admission.

Introduction

Tripura is India’s second-largest rubber-producing state after Kerala. Currently, it has over 70,000 hectares of rubber plantations, which is nearly 70% of the state’s land area, compared to less than 700 hectares in the mid-1970s [1]. Natural rubber is harvested from rubber trees in the form of latex by tapping and is coagulated by mixing it with formic acid before commercial processing. Since formic acid is easily accessible to rubber plantation workers, it is sometimes used for accidental ingestion or suicidal purposes [2]. Most cases are of suicidal intent, as accidental ingestion is less common due to the pungent odour of concentrated acid [3]. Early resuscitation, serial monitoring of parameters, and meticulous supportive treatment can significantly reduce complications and enhance the survival rate [4,5].

Case Series

Five cases of formic acid poisoning were referred to the Emergency Department with various clinical features. The pre-hospitalisation time ranged from 60-120 minutes. Four patients were females, and one was male. The age range of the patients was between 14 years and 70 years. The mode of ingestion was accidental in three cases and suicidal in two cases. The quantity ingested was between 15 mL and 30 mL of undiluted formic acid. Two patients had hypertension, which was controlled with antihypertensive medications. One patient had both hypertension and diabetes mellitus for 10 years, and both conditions were managed with antihypertensive and oral hypoglycaemic agents, respectively [Table/Fig-1].

Demographic profile of patients.

| Particulars | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 |

|---|

| Gender | F | F | F | F | M |

| Age (years) | 70 | 53 | 14 | 45 | 60 |

| Occupation | RPW | RPW | RPW | RPW | RPW |

| Co-morbidity | HTN/DM | HTN | - | - | HTN |

| Mode of ingestion | A | S | S | A | A |

| Quantity | 15 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 30 |

| Pre-hospitalisation time (minutes) | 60 | 120 | 120 | 80 | 90 |

F: Female; M: Male; RPW: Rubber plantation worker; HTN: Hypertension; DM: Diabetes mellitus; A: Accidental; S: Suicidal

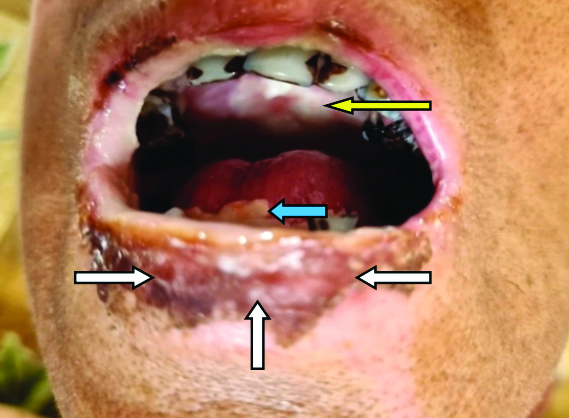

All patients presented with orofacial burns, dysphagia and upper abdominal pain. One patient experienced mild haematemesis, while another had severe haematemesis. Three patients exhibited altered mental status upon presentation [Table/Fig-2,3]. Immediate intensive care was established for all patients. Prophylactic antibiotics (Inj. cefoperazone 1 gm i.v. every 12 hours) were initiated and continued throughout their hospital stay. Catheterisation was performed to monitor urine output.

| Features | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 |

|---|

| Orofacial burn | + | + | + | + | + |

| Upper abdominal pain | + | + | + | + | + |

| Dysphagia | + | + | + | + | + |

| Dark/bright red urine | + | + | + | + | + |

| Haematemesis | - | - | - | Mild | Severe |

| Altered mental status | - | + | + | - | + |

+: Present; -: Absent

Orofacial (circumoral/upper palate/tongue) burn after formic acid poisoning showed with arrows.

Four patients developed dark cola-coloured urine within 12-24 hours of admission, and one patient had gross haematuria within four hours of hospitalisation [Table/Fig-4]. Blood investigations, including complete blood count, renal function tests with electrolytes, liver function tests, coagulation profile, chest X-ray and urine routine with microscopic examinations, were conducted at regular intervals. Haemoglobinuria was detected in all four patients with dark cola-coloured urine, suggestive of intravascular haemolysis. Urine routine and microscopy for the patient with haemoglobinuria showed a few Red Blood Cells (RBCs) and the presence of haemoglobin. The urine analysis of the patient who experienced gross haematuria revealed a significant number of RBCs without any dysmorphic RBCs and mild proteinuria (Protein 1+, Blood 3+).

Gross haematuria after formic acid poisoning.

Intravenous fluids were started immediately, and electrolyte levels along with acid-base analysis were performed by the intensivist, as soon as, possible upon hospitalisation [Table/Fig-5,6]. Gastric lavage or induced vomiting was not performed, and activated charcoal was not used in any patient. All patients exhibited dyselectrolytemia, with hyperkalemia being the most common electrolyte abnormality observed. Three patients developed metabolic acidosis, and a 7.5% NaHCO3 infusion was initiated for all of them [Table/Fig-7]. Metabolic acidosis was corrected in two patients. Injection omeprazole 40 mg i.v. was started in all of them every 12 hours, and sucralfate suspension 15 mL was administered orally three times a day when their mentation improved. A titrated dosage of steroids (dexamethasone 4 mg i.v. every 8 hours) was used in three patients who did not exhibit haematemesis or melena. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was not performed for any patient during the acute phase of poisoning. Topical anaesthetic gel (lignocaine 4%) and injectable tramadol were used to alleviate orofacial and upper abdominal pain. A diuretic (furosemide 20 mg i.v. once or twice daily) was used in four patients who presented with cola-coloured urine. Haemoglobinuria resolved in all patients with conservative management within 4-6 days of admission. Renal function and hyperkalaemia improved in four patients with acute renal toxicity after undergoing haemodialysis. Enteral feeding was initiated, as early as, possible once they could tolerate oral intake. Four patients survived and were discharged in stable condition within 10-16 days of admission, with advice to attend a Gastroenterology clinic for upper GI endoscopy [Table/Fig-7].

Electrolytes abnormalities.

| Electrolytes (Na/K/Cl) | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 |

|---|

| Admission | 137/4.9/104 | 135/5.0/102 | 138/4.8/103 | 136/4.9/104 | 136/6.2/108 |

| Day 2 | 136/5.5/106 | 136/5.4/103 | 137/5.3/105 | 137/5.6/104 | - |

| Day 3 | 137/5.9/108 | 135/5.9/104 | 138/5.8/106 | 139/6.0/106 | - |

| Day 4 | 138/5.6/104 | 136/5.1/103 | 137/5.0/103 | 136/5.5/102 | - |

| Day 7 | 139/4.6/104 | 138/4.8/104 | 140/4.2/104 | 137/5.0/103 | - |

Reference range of Na (Sodium): 135-145 mEq/L; K (Potassium): 3.5-5.2 mEq/L; Cl (Chloride): 96-106 mEq/L

| Parameters(pH/HCO3) | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 |

|---|

| Admission | 7.37/24 | 7.29/18 | 7.32/20 | 7.36/23 | 7.16/11 |

| Day 2 | 7.36/25 | 7.31/19 | 7.34/21 | 7.37/24 | - |

| Day 3 | 7.38/23 | 7.32/21 | 7.34/22 | 7.38/25 | - |

| Day 4 | 7.37/25 | 7.36/24 | 7.37/24 | 7.39/26 | - |

| Day 7 | 7.39/26 | 7.40/25 | 7.41/26 | 7.40/26 | - |

Reference range of arterial pH: 7.35 to 7.45; HCO3: 22-29 mEq/L

Complications, outcome and length of hospital stay.

| Complications | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 |

|---|

| Metabolic acidosis | - | + | + | - | + |

| Dyselectrolytemia | + | + | + | + | + |

| Acute renal toxicity | + | + | + | + | + |

| Hypovolemic shock | - | - | - | - | + |

| Outcome | S | S | S | S | D |

| Length of stay | 10 days | 14 days | 12 days | 16 days | 8 hours |

+: Present; -: Absent; S: Survived; D: Died

A 60-year-old patient who presented 90 minutes after accidental ingestion of 30 mL of acid exhibited severe metabolic acidosis, haematemesis and shock. He was intubated, and ventilatory support with volume-assisted control mode was established to maintain oxygen saturation. Patient experienced acute renal toxicity with hyperkalaemia and developed gross haematuria within four hours of admission. A 7.5% NaHCO3 infusion was started, and haemodialysis was initiated along with blood transfusion. An ultrasonography of the kidney and bladder did not reveal any abnormalities. Unfortunately, he succumbed to death due to severe metabolic acidosis and hypovolemic shock within eight hours of hospital stay.

Discussion

Formic acid poisoning is uncommon, and limited studies are available in the literature [5]. It is a colourless liquid with a pungent odour, and the fatal dose ranges from 15-200 mL [3]. The severity of symptoms depends on the amount ingested, with common presentations including orofacial burns, dysphagia, vomiting, respiratory distress, abdominal pain and haematemesis [4,5]. Various complications, such as metabolic acidosis, septicaemia, Gastrointestinal (GI) perforation, esophageal stricture, acute respiratory distress syndrome, aspiration pneumonia, severe skin burns, acute renal failure and shock, have been reported in the literature [3-5]. Septicemia, bowel perforation, tracheoesophageal fistula, aspiration pneumonia, haematemesis and haematuria are associated with a high mortality rate [6].

Formic acid is easily absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and can cause intravascular haemolysis and acute renal failure [7,8]. Patients should be admitted to a Critical Care Unit and kept nil per os. Gastric lavage should not be performed to prevent further damage to the gastrointestinal tract, which may lead to haemorrhage or perforation [7]. Fluid management must be conducted very carefully, and acid-base balance should be adequately maintained. Empirical antibiotics can be started, and renal function, urine output and electrolytes must be monitored regularly to detect acute renal toxicity [8].

Steroids should never be given in cases of severe gastrointestinal bleeding, as they can precipitate perforation [2,7]. In the present case series, a titrated dosage of steroids was used in three patients who did not experience haematemesis or melena during their hospital stay, assuming these patients did not have severe gastrointestinal bleeding. Upper GI endoscopy was not performed for any patient in the acute phase of poisoning, which aligns with findings from other studies described in the literature [2,7,9].

Severe clotting factor defects can be monitored by assessing bleeding time, clotting time, prothrombin time, serum fibrinogen and fibrin degradation products [7]. Folinic acid (1 mg/kg i.v. bolus followed by six doses of 1 mg/kg i.v. at four-hour intervals) can be used in severe cases to promote formate degradation in the liver [10]. Haemodialysis is required for severe metabolic acidosis, electrolyte imbalances and acute renal failure [8]. The authors performed haemodialysis on all five patients who had acute renal toxicity with dyselectrolytemia.

Diuretics should be used judiciously in acute renal failure. Although haematuria was rarely described, the exact cause of haematuria was not properly established, and it was associated with a high mortality rate [6,11]. It may occur within a few hours or after a day and may be due to systemic absorption of the acid causing toxic tubular necrosis of the kidney [11-13].

Estresa A et al., conducted a retrospective study on formic acid poisoning, which revealed that out of 15 deaths, six patients died from vascular hypotension, five from severe gastrointestinal bleeding, and the remaining four from acute renal failure [9]. Severe metabolic acidosis, haematemesis, haematuria, gastrointestinal perforation and advanced age were identified as independent predictors of mortality [3,7]. In the present case series, a 60-year-old patient presented to the hospital approximately 90 minutes after accidentally ingesting 30 mL of formic acid. He exhibited severe metabolic acidosis, haematemesis and gross haematuria. Despite all resuscitative measures, he died from hypovolemic shock within eight hours of admission.

Conclusion(s)

Increased age, co-morbidities, suicidal ingestion and a long pre-hospitalisation time contribute to a high mortality rate following formic acid poisoning. Immediate resuscitation and proper supportive measures can significantly reduce morbidity and mortality. Awareness should be raised among rubber plantation workers by educating them about the safe handling of the acid. Additionally, the incidence of suicidal ingestion of acid can be reduced by enforcing strict remedial measures.

F: Female; M: Male; RPW: Rubber plantation worker; HTN: Hypertension; DM: Diabetes mellitus; A: Accidental; S: Suicidal

+: Present; -: Absent

Reference range of Na (Sodium): 135-145 mEq/L; K (Potassium): 3.5-5.2 mEq/L; Cl (Chloride): 96-106 mEq/L

Reference range of arterial pH: 7.35 to 7.45; HCO

3: 22-29 mEq/L

+: Present; -: Absent; S: Survived; D: Died

[1]. Datta H, Debnath H, Shil P, Production and productivity of natural rubber: A study on growth-trends of rubber plantation in TripuraInt J M 2019 10:115-31.10.34218/IJM.10.4.2019.011 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[2]. More DK, Vora M, Wills V, Acute formic acid poisoning in rubber plantation workerIndian J Occup Environ Med 2014 18(1):29-31.10.4103/0019-5278.13495725006314 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Rajan N, Rahim R, Krishna S Kumar, Formic acid poisoning with suicidal intent: A report of 53 casesPostgrad Med J 1985 61:35-36.10.1136/pgmj.61.711.353991399 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Naik RB, Stephens WP, Wilson DJ, Walker A, Lee HA, Ingestion of formic acid-containing agents- Report of three fatal casesPostgrad Med J 1980 56:451-56.10.1136/pgmj.56.656.4517413552 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5]. Bhat RS, Naik SM, Goutham MK, Bhat CR, Appaji M, Chidananda KV, Acute formic acid poisoning: A case series analysis with current management protocols and review of literatureInt J Head Neck Surg 2014 59(3):104-07.10.5005/jp-journals-10001-1193 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[6]. Dalus D, Mathew AJ, Somarajan PS, Formic acid poisoning in a tertiary care center in South India: A 2-year retrospective analysis of clinical profile and predictors of mortalityJ Emerg Med 2013 44:373-80.10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.02.07923127861 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Naik SM, Ravishankara S, Appaji MK, Goutham MK, Devi NP, Mushannavar AS, Acute accidental formic acid poisoning: A common problem reported in rubber plantations in sulliaInt J Head Neck Surg 2012 3:101-10.10.5005/jp-journals-10001-1104 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[8]. Vyata V, Durugu S, Jitta SR, Khurana S, Jasti JR, An atypical presentation of formic acid poisoningCureus 2020 12(5):e798810.7759/cureus.7988 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[9]. Estresa A, Taylor W, Mills LJ, Platt MR, Corrosive burns of the esophagus and stomach: A recommendation for an aggressive surgical approachAnn Thorac Surg 1986 41:276-83.10.1016/S0003-4975(10)62769-53954499 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Moore DF, Bentley AM, Dawling S, Hoare AM, Henry JA, Folinic acid and enhanced renal elimination in formic acid intoxicationJ Toxicol Clin Toxicol 1994 32:199-204.10.3109/155636594090004518145360 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. Trakulsrichaia S, Mitprasatc A, Sriaphab C, Tongpoob A, Wongvisawakornb S, Rittilertb P, Hematuria, an unusual systemic toxicity, in formic acid ingestion: A case reportAsian Biomedicine 2016 10:189-90.10.5372/1905-7415.1002.481 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[12]. Inci M, Zararsiz I, Davarci M, Gorur S, Toxic effects of formaldehyde on the urinary systemTurk J Urol 2013 39(1):48-52.10.5152/tud.2013.01026328078 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[13]. Chou SH, Chang YT, Li HP, Huang MF, Lee CH, Lee KW, Factors predicting the hospital mortality of patients with corrosive gastrointestinal injuries receiving esophagogastrectomy in the acute stageWorld J Surg 2010 34:2383-88.10.1007/s00268-010-0646-620512491 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]