The Central Line-associated Bloodstream Infection (CLABSI) is defined as a laboratory-confirmed bloodstream infection where the same organism is isolated from both central and peripheral blood culture specimens in a patient who had a central line for 48 hours or more at the time of infection, with no other apparent source of infection. It requires no evidence of microbial growth on the suspected catheter [1]. Central Venous Catheters (CVCs) are needed for the delivery of drugs, parenteral nutrition, haemodialysis and for managing critically-ill patients [2]. Despite their immense benefits, catheter insertion may result in complications such as haematoma, arterial puncture or cannulation, pneumothorax, haemothorax, local insertion site infections and bloodstream infections [3,4]. CLABSIs, which can be prevented, are increasing because of changes in the varieties of microbes isolated and the increased use of broad-spectrum antibiotics [5].

The International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) reported that the overall CLABSI rate was higher (5.05 vs. 0.8 per 1,000 central line days) and in respiratory ICUs, the CLABSI rate was 2.47 (1.9-3.2, 95% CI) compared to 1.0 (0.5-1.9, 95% CI) reported by the US National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) in 2013 [6]. Recently, there has been a dispute regarding whether mortalities were due to CLABSI [7]. Pittet D et al., found that the mortality rate due to Catheter-related Bloodstream Infections (CRBSIs) was 35% [8], whereas others have failed to find mortality directly attributed to CRBSIs [9-11]. However, CRBSIs lead to a significant increase in healthcare costs, ranging from €3,124 to €25,641 per CRBSI, partly due to increased duration of hospital and ICU stays [9-11].

The CLABSIs worsen the clinical course of patients, leading to significant morbidity and mortality, along with increased healthcare costs [12,13]. Thus, implementing a prevention program is of paramount importance. It is therefore very important to diagnose such infections at the earliest by using clinical signs and symptoms together with blood culture. Till now, there have been only a handful of studies [14-17] conducted on CLABSI in India. Thus, this study was conducted to analyse the causative pathogens, risk factors for CLABSI and their outcomes, which would help in implementing more effective prophylactic standards.

Materials and Methods

A prospective cohort study was carried out in a 10-bed Respiratory ICU (RICU) at the Department of Pulmonary Medicine, SCB Medical College and Hospital, a tertiary-care teaching hospital in Cuttack, Odisha, India, from March 2021 to October 2022. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (730/4.06.2021).

Inclusion criteria:

Consenting patients aged ≥18 years.

Patients with a Central Venous Catheter (CVC) inserted for 48 hours or more after admission to the RICU as per the defined asepsis and antisepsis protocol in the ICU.

Exclusion criteria:

Patients whose catheter was inserted outside the hospital.

Patients with a skin infection at the site of central line insertion.

Non consenting patients.

All patients aged ≥18 years admitted to the RICU with CVCs for more than 48 hours were enrolled in the study using universal sampling.

Study Procedure

After 48 hours of the insertion of the CVC, all patients enrolled in the study were followed-up daily for the development of new-onset bloodstream infections. New-onset sepsis was suspected when two or more of the following conditions were present, along with suspicion of infection: fever (temperature >38°C) or hypothermia (<36°C), tachycardia (>100 beats/min), tachypnoea (>24 breaths/min) and either leukocytosis (>12,000/cumm) or leukopenia (<4,000/cumm) [18].

Upon suspicion of new-onset sepsis, two blood samples were collected 48 hours after central line insertion: one from the central catheter lumen and the other from a peripheral vein. Infection from other sources was excluded through physical examination, urine cultures, sputum cultures, tracheal aspirates and chest radiographs at the time of admission. If the same organism was isolated from both blood specimens, it was termed a positive case. All isolates obtained from cases of Central Line-associated Bloodstream Infections (CLABSI) were tested for antibiotic susceptibility using the Kirby-Bauer method, with interpretation as per Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) 2018 guidelines [19].

The recorded data included age, sex, BMI, co-morbidities, clinical signs and symptoms, underlying diagnosis, duration of hospitalisation, length of ICU stay, duration of catheterisation, indication for CVC insertion, site of CVC insertion, APACHE II score at admission [15,20], Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) Score at CVC insertion [15,20], microbial species identification, antimicrobial susceptibility of the pathogens and patient outcome (death or discharge).

Statistical Analysis

All calculations were done using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0. Group comparisons were performed by using an unpaired t-test. The Chi-square test was calculated and a p-value of <0.05 was considered significant for indicating differences between groups. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis was done for risk factors associated with the outcome of CLABSI.

Results

During the study period, among the 146 patients admitted to the RICU, 66 required CVC insertion for more than 48 hours, resulting in a total of 664 catheter days. A total of 20 cases of CLABSI were documented, accounting for 30.30% of the 66 patients with central lines. The CLABSI rate was calculated as 30.12 per 1,000 catheter days, determined by dividing the number of CLABSI cases by the number of catheter days and multiplied by 1,000, in accordance with NHSN (CDC) guidelines [21].

The demographic data, clinical parameters, predisposing factors and mortality of CLABSI cases are shown in [Table/Fig-1]. The mean age of patients with CLABSI was 62.85±14.95 years, with the most commonly affected age group being 55-74 years 13 (65%). Males 16 (80%) outnumbered females 4 (20%) in the CLABSI cases, resulting in a male to female ratio of 4:1. Variables such as diabetes mellitus, fever, duration of catheterisation, duration of hospitalisation, length of ICU stay and APACHE II score at ICU admission were significantly associated with the development of CLABSI. However, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of age, gender and BMI. Septic shock 7 (35%) remained the main reason for CVC insertion in patients with CLABSI, followed by difficult/lack of peripheral venous access and prolonged parenteral therapy 5 (25%) each. The most common insertion site that developed CLABSI was the femoral vein 5 (55.55%), followed by the internal jugular vein 13 (27.66%) and the subclavian vein 2 (20%). Of the 20 patients who developed CLABSI, 12 (60%) patients succumbed to the infection, while the rest 8 (40%) patients recovered with treatment.

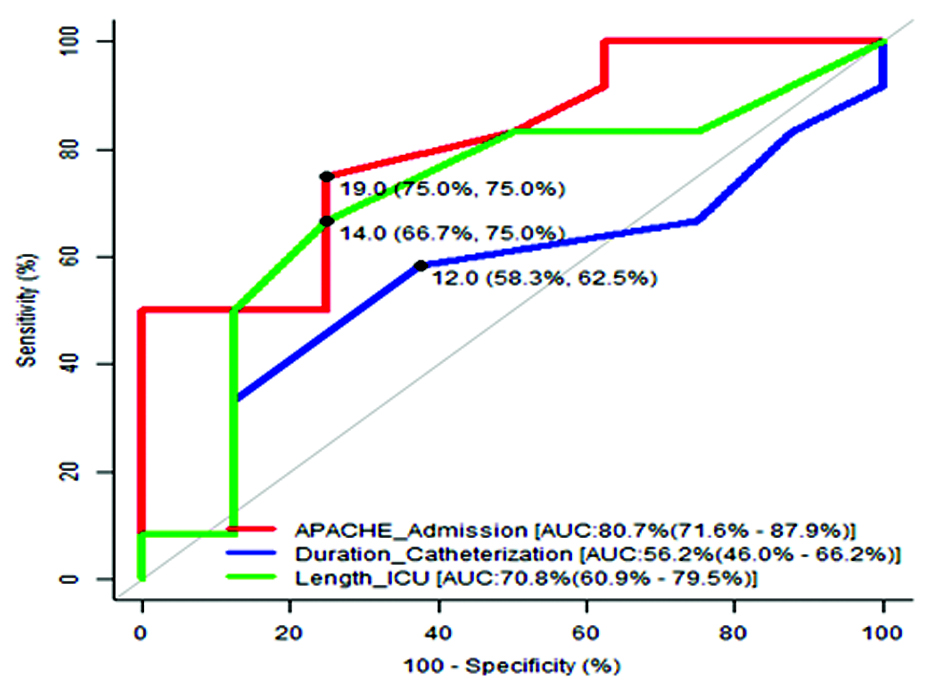

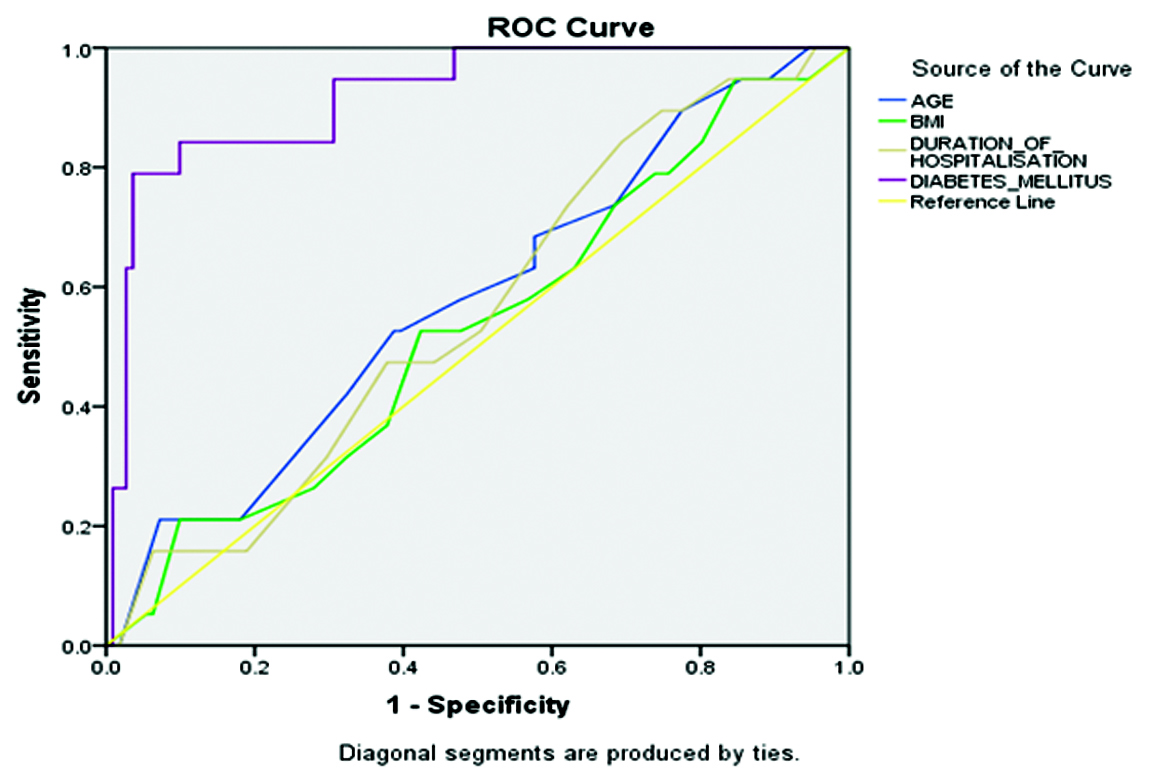

Multivariate analysis of variables that could be risk factors for CLABSI showed that length of ICU stay (p=0.003) and diabetes mellitus (p=0.012) were independent predictors of acquiring CLABSI [Table/Fig-2]. Unlike catheter duration, duration of hospitalisation, age and BMI, an APACHE II score at admission ≥19.0 was identified as the optimal cut-off, with 75.0% sensitivity and 75.0% specificity. A length of ICU stay ≥14 days was also determined to be an optimal cut-off, with 66.7% sensitivity and 75.0% specificity. Furthermore, diabetes mellitus (AUC=92.1%, sensitivity=81%, specificity=76.4%) significantly predicted mortality among patients with CLABSI [Table/Fig-3,4 and 5].

Demographic data, clinical characteristics, potential risk factors and mortality of CLABSI and non CLABSI cases (univariate analysis).

| Variables | CLABSI cases(n=20) | Non CLABSI cases (n=46) | p-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | 62.85±14.95 | 56.48±18.75 | 0.184 |

| Gender (%) |

| Male | 16 (80.0%) | 30 (65.2%) | 0.230 |

| Female | 4 (20%) | 16 (34.8%) |

| BMI (%) | 23.48±3.56 | 21.50±3.86 | 0.055 |

| Co-morbidities |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (55%) | 08 (17.3%) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 11 (55%) | 14 (30.4%) | 0.058 |

| Malignancy | 01 (5%) | 02 (4.3%) | 0.093 |

| Hypothyroidism | 02 (10%) | 00 | 0.162 |

| HIV | 00 | 01 (2.2%) | 0.665 |

| Symptoms and signs |

| Fever | 17 (85%) | 25 (54.34%) | 0.017 |

| Tachycardia | 10 (50%) | 30 (65.22%) | 0.244 |

| Tachypnoea | 06 (30%) | 12 (26.08%) | 0.742 |

| TLC |

| <12,000/cumm | 00 | 08 (100%) | 0.114 |

| >12,000/cumm | 20 (34.5%) | 38 (65.5%) |

| Underlying diagnosis |

| Obstructive airway disease | 12 (42.85%) | 16 (57.14%) | 0.065 |

| Restrictive lung disease | 1 (33.33%) | 2 (66.67%) | 0.215 |

| Pneumonia | 3 (15%) | 17 (85%) | 0.146 |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 1 (20%) | 4 (80%) | 0.718 |

| Others | 3 (30%) | 7 (70%) | 0.827 |

| Indication of central line insertion |

| Difficult peripheral venous access | 5 (25%) | 21 (45.65%) | 0.812 |

| Administration of irritant drugs | 1 (5%) | 7 (15.21%) | 0.124 |

| Septic shock | 7 (35%) | 17 (37%) | 0.237 |

| Other aetiology of shock | 2 (10%) | 1 (2.1%) | 0.078 |

| Prolonged parenteral therapy | 5 (25%) | 0 | 0.871 |

| Catheter insertion site |

| Internal jugular vein | 13 (27.66%) | 34 (72.34%) | 0.612 |

| Femoral vein | 5 (55.55%) | 4 (44.44%) | 0.415 |

| Subclavian vein | 2 (20%) | 8 (80%) | 0.248 |

| Duration of catheterisation | 11.75±2.59 | 9.33±1.03 | 0.001 |

| Duration of hospitalisation | 17.05±4.53 | 10.83±1.74 | 0.001 |

| Length of ICU stay | 13.80±3.41 | 9.59±1.34 | 0.001 |

| APACHE II score at admission | 20.85±5.50 | 17.73±5.42 | 0.041 |

| SOFA Score at CVC insertion | 10.05±3.57 | 9.89±1.34 | 0.757 |

| Outcome |

| Death | 12 (60%) | 32 (69.6%) | 0.574 OR (CI)=1.52 |

| Alive | 08 (40%) | 14 (30.4%) | (0.51-4.54) |

HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; TLC: Total leucocyte count; Mean±SD or number of patients

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for CLABSI.

| Variables | Adjusted OddsRatio (OR) | Confidence interval of OR | p-value |

|---|

| Presence of co-morbidities | 2.227 | 0.319-15.523 | 0.419 |

| Age | 1.077 | 0.991-1.171 | 0.081 |

| BMI | 1.216 | 0.954-1.549 | 0.114 |

| Length of ICU stay | 7.592 | 2.015-28.609 | 0.003 |

| Duration of catheterisation | 0.265 | 0.058-1.549 | 0.089 |

| Duration of hospitalisation | 8.137 | 3.612-19.177 | 0.132 |

| APACHE II score at admission | 11.218 | 5.817-26.402 | 0.714 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.411 | 0.813-2.326 | 0.012 |

Association of risk factors with outcome among CLABSI.

| Risk factors | Area under the curve | 95%CI | Youden index | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|

| APACHE II score at admission | 0.807 | 0.716-0.879 | 0.5 | 75% | 75% |

| Duration of catheterisation | 0.563 | 0.46-0.662 | 0.208 | 58.3% | 62.5% |

| Length of ICU stay | 0.708 | 0.609-0.795 | 0.417 | 66.7% | 75% |

| Age | 0.579 | 0.434-0.748 | 0.329 | 65.8% | 72.4% |

| BMI | 0.531 | 0.389-0.683 | 0.311 | 64.3% | 76.6% |

| Duration of hospitalisation | 0.559 | 0.376-0.721 | 0.341 | 62.7% | 73.8% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.920 | 0.838-0.946 | 0.732 | 81% | 76.4% |

ROC curve of some risk factors for outcome among CLABSIs.

ROC curve of different risk factors for outcome among CLABSIs.

The Gram-positive bacteria were the most common organisms isolated from CLABSI 12 (60%), followed by Gram-negative organisms 8 (40%). Acinetobacter 6 (30%) was the most common pathogen isolated, followed by Enterococcus 5 (25%), Staphylococcusaureus 4 (20%), Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcusaureus (MRSA) 2 (10%), Pseudomonas 2 (10%) and Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci (CoNS) 1 (5%) as shown in [Table/Fig-6]. The antibiotic sensitivity patterns for the organisms causing CLABSI in the current study as shown in [Table/Fig-7]. All Gram-positive organisms were 100% sensitive to Linezolid and Vancomycin. Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA and Enterococcus were 100% sensitive to Teicoplanin. CoNS were 100% sensitive to Gentamicin, whereas MRSA was 100% resistant to Gentamicin. MRSA, CoNS and Enterococcus were 100% resistant to Erythromycin, whereas, CoNS were 100% resistant to Amoxicillin. MRSA was 100% sensitive to Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMZ) but CoNS showed 100% resistance. The sensitivity rate of Gram-negative isolates to both Polymyxin-B and Tigecycline was 100%, in contrast to Ciprofloxacin, which was 100% resistant. Pseudomonas was 50% sensitive to Imipenem, Gentamicin, Amikacin, Piperacillin-Tazobactam and Ceftazidime, while being 100% resistant to Cefepime. Acinetobacter was 50% sensitive to Meropenem and Imipenem, whereas it was 100% resistant to Gentamicin and Ciprofloxacin.

The microbiological causes of CLABSIs.

| Organism | Number (percentage out of 20 CLABSI cases) |

|---|

| Gram-negative bacteria |

| Acinetobacter | 6 (30%) |

| Pseudomonas | 2 (10%) |

| Total Gram-negative bacteria | 8 (40%) |

| Gram-positive bacteria |

| Enterococcus | 5 (25%) |

| S. aureus | 4 (20%) |

| Methicillin-resistant S. aureus | 2 (10%) |

| Coagulase negative Staphylococcus | 1 (5%) |

| Total Gram-positive bacteria | 12 (60%) |

Antibiotic susceptibility of Gram-positive and Gram-negative isolates in central line-associated bloodstream infection cases.

| S,R (Sensitivty%) |

|---|

| Antibiotics | Erythromycin | Clindamycin | TMP-SMZ | Ciprofloxacin | Gentamycin | Linezolid | Vancomycin | Doxycyclin | Teicoplanin | Amoxycillin | Meropenem | Imipenem | Amikacin | Piperacillin-Tazobactam | Ceftazidime | Cefepime | Minocycline | Polymixin-B | Tigecycline |

|---|

| S.aureus(4 cases) | 1,3(25%) | 2,2(50%) | 2,2(50%) | 1,3(25%) | 2,2(50%) | 4,0100%) | 4,0(100%) | 2,2(50%) | 4,0(100%) | 1,3(25%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| MRSA(2 cases) | 0,2 | 1,1(50%) | 2,0(100%) | NA | 0,2 | 2,0(100%) | 2,0(100%) | 1,1(50%) | 2,0(100%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| CoNS(1 case) | 0,1 | 1,0(100%) | 0,1 | NA | 1,0(100%) | 1,0(100%) | 1,0(100%) | 0,1 | NA | 0,1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Enterococcus(5 cases) | 0,5 | 1,4(20%) | NA | 1,4(20%) | NA | 5,0(100%) | 5,0 (100%) | 4,1(80%) | 5,0(100%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Acinetobacter(6 cases) | NA | NA | NA | 0,6 | 0,6 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 3,3(50%) | 3,3(50%) | 1,5(16.6%) | 2,4(33.3%) | 2,4(33.3%) | 1,5(16.6%) | 4,2(66.67%) | 6,0(100%) | 6,0100%) |

| Pseudomonas(2 cases) | NA | NA | NA | 0,2 | 1,1(50%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2,0(100%) | 1,1(50%) | 1,1(50%) | 1,1(50%) | 1,1(50%) | 0,1 | NA | 2,0(100%) | 2,0(100%) |

Note: S: Sensitive, R: Resistant, CoNS: Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus

Discussion

The present prospective observational study assessed the aetiology, risk factors and outcomes of CLABSI in patients admitted to the RICU of a tertiary care hospital. In the present study, the rate of CLABSI in our RICU was 30.12 per 1000 catheter-days, which is significantly higher than the 15.27 and 17.04 per 1000 catheter-days reported by Mehta S et al., and Mishra SB et al., respectively [14,15]. However, Patil HV et al., reported a CLABSI rate of 47.31 per 1000 catheter-days [22].

The mean age of affected patients in this study was 62.85±14.95 years, with a male to female ratio of 4:1. This finding is consistent with the studies by Wittekamp BH et al., and Pawar M et al., and there was no statistically significant difference in terms of age and sex [7,23]. The higher incidence of CLABSI in the present study may be due to the elderly study population and central line insertions were predominantly performed as emergency procedures. However, Callister D et al., reported that CLABSI was more commonly associated with female sex [24].

The mean BMI of patients with CLABSI in this study was 23.48±3.56 kg/m2, which is similar to the findings of Pawar M et al., whereas, Trick WE et al., reported that a high BMI remained an independent predictor for poor dressing condition [23,25]. In the present study, diabetes mellitus showed a significant association with the acquisition of CLABSI (p=0.001), which is in accordance to Hajjej Z et al., and Tarpatzi A et al., [20,26]. However, Pawar M et al., observed that diabetes mellitus was not significantly associated with CLABSI [23].

In the present study, patients with obstructive airway disease, pneumonia, restrictive lung disease, other pulmonary pathologies and pulmonary tuberculosis were not significantly associated with acquiring CLABSI whereas, Baier C et al., observed that pre-existing pulmonary disease was an independent risk factor for acquiring CLABSI [27]. This discrepancy warrants further investigation in future studies.

The increased incidence of CLABSI in cases with femoral lines may be attributed to the proximity of the femoral line to the perineal region. Earlier data showed an increased risk of developing infectious complications when using femoral access, consistent with the present study findings [28-30]. Some studies reported that Internal Jugular Vein (IJV) catheters are more prone to cause CRBSI [31-34], while other studies revealed no significant association [14,35].

In this study, the most common positive physical examination finding in patients with CLABSI was fever (85%), which was significant (p=0.017). The next most common sign was tachycardia (p=0.244), followed by tachypnoea (p=0.742) and the total leukocyte count was not statistically significant (p=0.114). These findings are comparable to those of a study conducted by Maj Kumar A et al., A comparison of similar studies is presented in [Table/Fig-8] [14,15,20,28,36].

Comparison of national and international studies with present study [14,15,20,28,36].

| S. No. | Author’s name and year | Place of study | Number of subjects | Objectives | Parameters assessed | Conclusion |

|---|

| 1 | AI-Khawaja S et al., (2021) [28] | Adult ICU at Salmaniya Medical Complex, Kingdom of Bahrain | 1634 patients | To define the trends of the rates of CLABSI over 4 years, it’s predicted risk factors, aetiology and the antimicrobial susceptibility of the isolated pathogens. | Age, gender, underlying disease, site, duration and location of central line insertion, duration of ICU stay before central line placement, pathogen isolates, antibiotic susceptibility of isolates, outcome. | Average CLABSI rate- 3.2/1000 central line days.Its rate was higher when using femoral access, longer duration of ICU stay and central line, Inserting central line outside ICU setting.The Gram-negative organisms were predominant. The most common offending organisms were CoNS, and Acinetobacter. MDR organisms- 56% of CLABSI.High mortality rate among CLABSI cases (44%). |

| 2 | Mehta S et al., (2020) [14] | Department of Microbiology, MM Institute of Medical Science and Research, Ambala, Haryana, India | 60 patients | To determine the incidence of CRBSI in the ICU and to identify the factors influencing it and the organisms involved in its causation. | Age, gender, site and duration of CVC insertion, pathogen identification, antimicrobial susceptibility, Clinical outcome. | CRBSI rate- 15.27 per 1000 catheter days, incidence- 16.67%.The Gram-negative organisms were predominant and A. baumanni was predominant isolates (40%).All MRSA isolates were sensitive to Linezolid (100%) and Vancomycin (100%) and all Gram-negative isolates were resistant to most of the antibiotics except for colistin. Duration of catheterisation and clinical outcome were significantly associated with development of CLABSI. |

| 3 | Mishra SB et al., (2016) [15] | Medical ICU of Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, India | 153 patients | Incidence, risk factors and associated mortality of CLABSI in adult ICU in India. | Age, gender, underlying diagnosis, co-morbidities, SOFA score, APACHE II score, central line days, length of ICU stay, mortality, pathogen isolates. | CLABSI rate- 17.04/1000 catheter days.Immunosuppression, age >60 yrs, central line days >10 days, length of ICU stay >21 days leads to higher CLABSI cases.K. pneumoniae was the most common isolate.CLABSI associated mortality- 56%.SOFA and APACHE II scores associated with higher mortality. |

| 4 | Hajjej Z et al., (2014) [20] | ICU, Millitary Hospital of Tunis, 1008 Montfleury, Tunis, Tunisia | 260 patients | Incidence, microbiological profile and risk factors for CRBSI. | Age, gender, APACHE II at admission, co-morbidities, duration and site of central line, Sepsis at insertion, length of ICU stay, pathogen isolates, antibiotic susceptibility, mortality. | CRBSI rate- 2.4/1000 catheter days.Diabetes mellitus, long duration of catheterisation and sepsis at insertion associated with CRBSI.Mortality among CRBSI cases- 21.8%.Predominant microbe isolated was Gram-negative bacilli.All Gram-negative isolates among dead patients were XDR. |

| 5 | Present study | RICU of SCB MCH, Cuttack, Odisha, India | 66 patients | To identify the organisms involved in the causation of central line associated infections and to study the various risk factors influencing development of the CVC infections and its outcome. | Age, sex, BMI, co-morbidities, clinical profile, underlying diagnosis, duration of hospitalisation and ICU stay, indication, site and duration of catheterisation, APACHE II score, SOFA score, pathogen isolated, antimicrobial susceptibility of the pathogens and outcome. | CLABSI rate-30.12/1000 catheter days.Prolonged duration of catheterisation, hospital stay, ICU stay, APACHE II score, Diabetes mellitus significantly associated with CLABSI cases.Predominance of the Gram-positive bacteria.All strains of Gram-positive isolates were 100% sensitive to linezolid, teicoplanin and vancomycin and all strains of Gram-negative isolates were 100% sensitive to polymyxin B and tigecycline. |

In this study, the rate of CLABSI increased with longer durations of hospitalisation, ICU stays, catheterisation and higher APACHE II scores at admission to the RICU. Studies by Balaji B et al., Dimick JB et al., and Pittet D et al., revealed that the median hospital stay was longest among CRBSI patients [16,37,38]. In this study, the average duration of hospitalisation (17.05±4.53; p=0.001) and the average length of ICU stay (13.80±3.41; p=0.001) were significantly higher in CLABSI patients, which is in accordance with previously published data [7,23,39]. However, according to the study by Hajjej Z et al., the length of ICU stay was not significantly associated with CLABSI patients (p=0.079) [20].

In the current study, the duration of catheterisation was also identified as a significant risk factor for acquiring CLABSI (p=0.001), which aligns with findings from Mishra SB et al., [15], while analysis of risk factors revealed that the APACHE II score at ICU admission was significantly associated with the occurrence of CLABSI (p=0.041), which is in accordance with Hajjej Z et al., and Pawar M et al., [20,23]. This shows that an abnormal physiological status during ICU admission increases the incidence of catheter-related bloodstream infections.

In this study, among the risk factors, the length of ICU stay was independently associated with CLABSI (adjusted OR=7.592, 95% CI=2.015-28.609; p=0.003) and patients with Diabetes Mellitus (adjusted OR=1.411, 95% CI=0.813-2.326; p=0.012) had greater odds of developing CLABSI. Accordingly, Mishra SB et al., Hajjej Z et al., and Tarpatzi A et al., reported that an immunosuppressed state and the duration of catheterisation were independent predictors of acquiring CLABSI [15,20,26].

In this study, the overall mortality was 66.7% and the mortality associated with CLABSI was 60%. Mishra SB et al., showed an overall mortality of 46% and a CLABSI-associated mortality of 56% [15]. The variability in the present study compared to the aforementioned studies is because our study population comprising chronically ill patients with co-morbidities.

While analysing the risk factors associated with outcomes among CLABSI patients in this study, ROC analysis was performed for the APACHE II score at admission, age, BMI, diabetes mellitus, duration of catheterisation, hospitalisation and ICU stay to determine cut-off values. This study revealed that the APACHE II score at admission (AUC=0.807) had an optimal cut-off of 19 (75.0% sensitivity, 75.0% specificity), the length of ICU stay (AUC=0.708) had an optimal cut-off of 14 days (66.7% sensitivity, 75.0% specificity) and diabetes mellitus (AUC=0.920) had 81% sensitivity and 76.4% specificity, significantly predicting mortality among CLABSI patients. Similarly, Mishra SB et al., showed that SOFA >10 (p=0.05) and APACHE II score >20 (p=0.07) had a tendency towards significance for mortality [15].

In this study, Acinetobacter was the most common pathogen cultured (30%), followed by Enterococcus (25%). The overall most common organisms isolated from CLABSI cases were Gram-positive bacteria (60%), followed by Gram-negative bacteria (40%). This finding is similar to what has been reported in other studies [39-41]. In a study by Ujesh SN et al., S. aureus was the predominant pathogen, followed by S. haemolyticus, Acinetobacter, Klebsiella and E. coli [17]. Accordingly, AI-Khawaja S et al., reported that Gram-negative bacteria were the predominant pathogens (56%), followed by Gram-positive bacteria (41%) and Candida (3%) [28]. The differences in findings were primarily due to variations in local bacteriologic ecology across different study sites and differences in their empirical antibiotic usage.

All strains of Gram-positive organisms, including MRSA, were 100% sensitive to linezolid, teicoplanin and vancomycin. Additionally, all strains of Gram-negative pathogens were 100% sensitive to polymyxin B and tigecycline, which is comparable to observations made by AI-Khawaja S et al., and Ujesh SN et al., [17,28]. The majority of strains were Multidrug-Resistant (MDR).

Limitation(s)

Firstly, the present study had a small cohort size, which leads to a lack of diverse clinical profiles, potentially making the results inaccurate. Secondly, the authors conducted this investigation at a single institution. Thirdly, a semiquantitative culture of all the catheters from suspected cases of CLABSI could not be performed, as the surveillance definition used for diagnosing CLABSI did not allow for it. Fourthly, fungi as the causative organisms of CLABSI in every patient were not taken into account. Lastly, the authors did not collect data after any interventions that could have resulted in a reduction of CLABSI rates.

Conclusion(s)

The incidence of CLABSI was high, with significant risk factors including prolonged catheterisation, extended hospital stays, longer ICU stays, higher APACHE II scores and diabetes mellitus. Gram-positive bacteria were predominant, followed by Gram-negative bacteria, with a significant proportion of MDR organisms. Therefore, active intervention is required for timely diagnosis to decrease the morbidity and mortality associated with central Venous Catheter-related Bloodstream Infections (CVC-BSIs). Maximal sterile techniques, proper aftercare and regular monitoring of the CVC are essential to determine the necessity of its continued use. Addressing the local microbial profile, the prevalence of MDR bacteria causing CLABSI and their antibiotic susceptibility patterns may help the physicians in initiating empirical antibiotic therapy until bacterial cultures and their antibiotic sensitivity pattern available.

HIV: Human immunodeficiency virus; TLC: Total leucocyte count; Mean±SD or number of patients

Note: S: Sensitive, R: Resistant, CoNS: Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus