Case Report

A 23-year-old primigravida, at 29 weeks of gestation, was referred presented at a tertiary care with preterm labour. She complained of severe abdominal pain, backache, and vaginal leakage for two days. On examination, she was pale, afebrile, and had a normal pulse rate and blood pressure. The foetal heart rate was regular at 150 beats per minute. Physical examination revealed an oedematous abdominal wall and a gravid uterus measuring 34 weeks in size with vertex presentation. The uterus could not be felt separately from the tumour masses. She experienced a preterm vaginal delivery, resulting in the birth of a female foetus weighing 1.6 kg.

Her antenatal history indicated that at 20 weeks of gestation, she presented with pain in the left iliac fossa. Ultrasound showed bilateral solid-cystic ovarian masses, which were most likely malignant. The Magnetic Resonance of Imaging (MRI) revealed a large, well-defined, solid-cystic right ovarian mass measuring 16×13×7 cm, as well as a similar left ovarian mass measuring 8.6×8×5 cm. The possibility of bilateral cystadenocarcinomas was suggested, and moderate ascites was also noted. Serum AFP was 38.61 ng/mL (normal range: 0.89-8.78 ng/mL), serum CEA was 54.23 ng/mL (normal range: 0-5 ng/mL), serum β-HCG was 39,244.89 mIU/mL (normal range: 5-25 mIU/mL), and serum CA125 was 151.9 U/mL (normal range: 0-35 U/mL). Ultrasound-guided biopsies of both ovarian masses were performed, and histopathology revealed high-grade adenocarcinoma, favouring metastatic carcinoma. The patient was advised to undergo an endoscopy to investigate for a primary tumour in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroduodenoscopy revealed multiple subcentimetric nodules in the duodenum, which showed focal active duodenitis on histopathology.

Immunohistochemistry markers were positive for CK20 and EMA, and negative for AFP and CD30, suggesting a primary tumour in the gastrointestinal tract. Laboratory investigations showed the following: haemoglobin 8.6 mg/dL (normal range: 12-14 mg/dL), total white blood cell count 20.6×109/L (normal range: 4.5-11.0×109/L), neutrophils 89% (normal range: 55-70%), lymphocytes 21% (normal range: 20-40%), platelet count 210,000/cmm (normal range: 150,000-300,000/cmm), blood urea nitrogen 8 mg% (normal range: 6-24 mg%), and creatinine 1.1 mg/dL (normal range: 0.6-1.1 mg/dL). Serum sodium levels were 125 mEq/L (normal range: 135-146 mEq/L), while serum potassium and chloride levels were normal. Hyponatremia was corrected.

On the 5th postnatal day, the patient developed drowsiness that progressed to altered sensorium. She was transferred to intensive care and placed on ventilator support. There was no fever or seizures, and a Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the brain was normal. The patient’s condition continued to deteriorate, with blood pressure dropping to unrecordable levels. She succumbed to her illness on the 9th postnatal day. A complete autopsy was performed.

Autopsy Findings

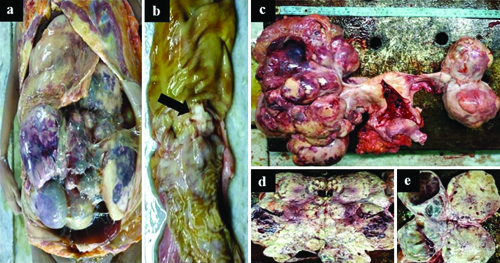

On external examination, the deceased was thinly built, pale, and had a distended abdomen with a girth of 110 cm. Upon opening the abdominal cavity, 150 mL of dark-brown hazy fluid oozed out [Table/Fig-1a]. A puerperal uterus and bilateral large ovarian masses were observed, along with a few tiny peritoneal nodules [Table/Fig-1c]. The right ovarian mass measured 40×26×14 cm and weighed 2 kg [Table/Fig-1d], while the left ovarian mass measured 20×10×6 cm and weighed 600 g [Table/Fig-1e]. Both ovarian tumours were bosselated, creamy-white, solid-cystic, and contained brownish fluid in the cysts. A 2×1 cm ulceroproliferative gray-white tumour was found in the sigmoid colon, located 20 cm from the rectum [Table/Fig-1b]. The tumour involved the full thickness of the colonic wall and extended through the overlying serosa. Both lungs were normal in size and shape, and no metastases were observed. The heart and both lungs appeared normal. Fibrinous pericarditis was noted, and fresh thromboembolic material was observed protruding from the right pulmonary artery. The brain, liver, spleen, and other organs were normal.

a) In-situ examination showing large, bilateral ovarian tumours filling the abdominal cavity and obscuring other organs; b) Ulceroproliferative greyish-white growth (black arrow) in the sigmoid colon measuring 2×1.5×0.8 cm with breach of the serosa; c) Puerperal uterus with bilateral ovarian tumours having bosselated surface and an intact capsule; d) Right ovarian tumour, solid-cystic, measuring 40×26×14 cm, weighing 2 kg; e) Left ovarian tumour, solid-cystic, measuring 20×10×6 cm, weighing 600 grams.

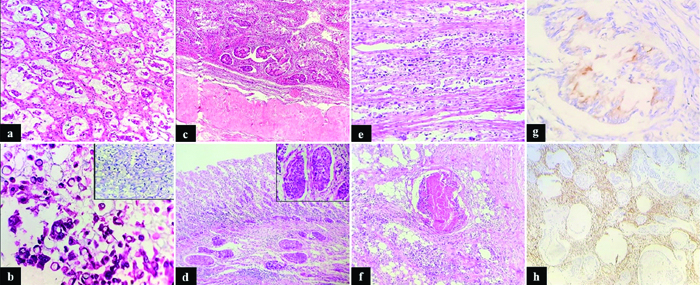

Histopathology of the sigmoid colon tumour revealed signet-ring cell carcinoma, with 60-70% of the tumour exhibiting signet-ring cell morphology, extensively infiltrating the muscularis propria and serosa [Table/Fig-2e]. The signet-ring cells contained classic mucin-rich vacuoles in their cytoplasm. Both ovarian masses displayed similar histomorphological features [Table/Fig-2a,b] with infiltration into the ovarian stroma [Table/Fig-2c]. The tumour was composed of lobules, sheets, and a few glands of malignant epithelial cells separated by fibrous stroma. Individual tumour cells were columnar to round, with hyperchromatic, markedly pleomorphic nuclei and finely granular chromatin. Pools of extracellular mucin with suspended malignant cells [Table/Fig-2a,b], large areas of necrosis, and lymphovascular emboli [Table/Fig-2d] were also present throughout the tumour. The immunohistochemical profile showed focal CK20 positivity in malignant cells [Table/Fig-2g] and vimentin positivity in the stromal cells [Table/Fig-2h]. CK7, CDX2, AMACR, ER, and PR were negative. A diagnosis of bilateral Krukenberg tumours of the ovaries, with metastatic peritoneal nodules, was made [Table/Fig-2f].

a) Ovarian tumour showing clusters of malignant cells and signet ring cells amidst pools of mucin (H&E, 100x); b) Malignant signet ring cells floating in the pools of mucin (H&E, 400x) Inset showing an Alcian blue stain highlighting the signet ring cells (Alcian blue stain, 400x); c) Tumour cells infiltration in the ovarian stroma (H&E, 40x); d) Prominent vascular emboli seen in the lamina propria of the sigmoid colon (H&E, 40x) Inset shows high power view of vascular emboli (H&E, 400x); e) Tumour cells extensively infiltrating the muscularis propria and serosa of the sigmoid colon (H&E, 400x); f) Metastasis to peritoneum with comedonecrosis (H&E, 100x); g) Focal CK20 positivity in the malignant glands (H&E, 400x); h) Vimentin positivity in the stromal cells (H&E, 400x).

Thromboembolism of the right pulmonary artery was confirmed histologically. Histopathology of the rest of the organs was normal. The cause of death was determined to be septicaemia and Pulmonary Thromboembolism (PTE) in a case of signet-ring cell carcinoma of the sigmoid colon, with bilateral Krukenberg tumours and peritoneal dissemination.

Discussion

KT is a metastatic malignancy of the ovary characterised by signet-ring adenocarcinoma, arising from a primary gastrointestinal malignancy [1]. KTs are named after Friedrich Ernst Krukenberg (1871-1946), who first described this tumour in 1896 [2].

KTs account for 1-2% of all ovarian cancers [3]. They are secondary ovarian tumours that have histological diagnostic criteria of more than 10% of the tumours showing mucin-rich signet cells [1]. KTs are bilateral in 63% of cases, with the stomach being the most common primary site; approximately 70% of tumours arise from the stomach [4]. Other tumours that give rise to ovarian metastases include those from the appendix, colon, breast, small intestine, rectum, gallbladder, and urinary bladder, in order of frequency [4]. The modes of spread of tumour cells to the ovaries include direct spread, transcoelomic spread, haematogenous spread, and lymphatic spread [1].

Diagnosis of KT during pregnancy is difficult, as symptoms such as nausea and vomiting caused by gastric cancers are non specific and are often presumed to be due to pregnancy [1,5,6]. Additionally, many of the tumour markers which are used to diagnose ovarian cancers, such as HCG, CEA, CA125, and AFP, are difficult to interpret during pregnancy, as they are also produced by the foetus [7]. Among the tumours encountered during pregnancy, the most frequent are those from the breast, thyroid, uterine cervix, Hodgkin’s disease, ovarian tumours, acute and chronic leukaemia, and lymphoma [8].

The most common presenting symptoms are pelvic mass and abdominal and pelvic pain. Less frequent symptoms include increased abdominal girth, ascites, postmenopausal bleeding, virilisation, and hirsutism [1,4]. However, worsening abdominal pain, ascites, virilisation, and persistent hyperemesis gravidarum during pregnancy should alert the physician to consider other diagnosis [1,4,7].

These tumours exhibit a bosselated external surface, while the cut surface is solid-cystic and firm, with oedematous to gelatinous areas. The microscopic appearance depends on the origin of the primary tumour [1]. Signet-ring cells may not be prominent and can be overshadowed by other microscopic features. They may be seen only in focal areas of the tumour, necessitating extensive sections to be evaluated [1].

Diagnosis is challenging, as secondary ovarian tumours must be differentiated from primary ovarian tumours, since the treatment differs for each. The differential diagnosis for KT includes primary ovarian mucinous tumours or primary ovarian endometrioid tumours [1,9,10]. Features such as bilaterality, nodular appearance of the tumour, surface tumour deposits, presence of signet-ring cells, extensive lymphovascular invasion, and single-cell invasion favour a secondary tumour rather than a primary tumour [1,9,10]. The immunohistochemistry profile, including CK7, CK20, CEA, CA125, MUC5AC, CDX2, P504S, ER/PR, and vimentin, is the mainstay of diagnosis [1,10]. KTs are observed to grow rapidly after delivery, and oestrogen receptors have been found in them [1]. The primary malignancy in KT is sometimes occult, and even thorough examination of the gastrointestinal tract may not reveal the primary tumour. In the current case, the primary malignancy in the sigmoid colon was detected only at autopsy.

Venous thromboembolism is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in cancer patients. In an autopsy study conducted by Gimbel IA et al., on 9,571 cancer patients, 1,074 (90.2%) had PTE [11]. PTE of the right pulmonary artery and septicaemia in the current autopsy case led to the patient’s death. According to statistics available on the website of the MD Anderson Cancer Centre, 3% of deaths in non hospitalised cancer patients treated with chemotherapy are caused by pulmonary PTE, while 10% of deaths in hospitalised cancer patients are attributed to PTE. The aetiology of PTE is multifactorial; cancers can induce PTE through the secretion of prothrombotic molecules, tumour necrosis factor, interleukin-like substances, and other factors that cause the upregulation of the coagulation cascade, increased platelet activation, and aggregation, all of which promote thrombosis.

Conclusion(s)

KTs are very aggressive tumours with a poor prognosis. Treatment involves robust chemotherapy and surgical debulking. Foetal survival is good with majority of pregnancies resulting in the delivery of a healthy baby. The poor prognosis of KTs emphasises the importance of early diagnosis and treatment.

[1]. Lerwill MF, Young RH, Metastatic tumours of the ovary. Kurman RJ (ed)Blaustein’s Pathology of the Female Genital Tract 2019 7th edNew YorkSpringer:949-60. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Classic pages in obstetrics and gynecology: Friedrich Ernst Krukenberg: Fibrosarcoma ovarii mucocellulare (carcinomatodes). Archiv für Gynäkologie, vol 50, pp. 287-321, 1896Am J Obstet Gynecol 1973 117(4):5754591259 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[3]. Yakushiji M, Tazaki T, Nishimura H, Kato T, Krukenberg tumours of the ovary: A clinicopathpathologic analysis of 112 casesNihon Sanka Fujinka Gakkai Zasshi 1987 39(3):479-85. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Kiyokawa T, Young RH, Scully RE, Krukenberg tumours of the ovary: A clinicopathologic analysis of 120 cases with emphasis on their variable pathologic manifestationsAm J Surg Pathol 2006 30(3):277-99. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Zhang Y, Du H, Li T, Li H, Deng Y, Wu R, Krukenberg tumour of gastric origin in pregnant women with preeclampsiaCase Rep Oncol 2023 16(1):718-27. [Google Scholar]

[6]. Boussios S, Moschetta M, Tatsi K, Tsiouris AK, Pavlidis N, A review on pregnancy complicated by ovarian epithelial and non-epithelial malignant tumours: Diagnostic and therapeutic perspectivesJ Adv Res 2018 12:01-09. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Co PV, Gupta A, Attar BM, Demetria M, Gastric cancer presenting as a krukenbergtumour at 22 weeks’ gestationJ Gastric Cancer 2014 14(4):275-78.10.5230/jgc.2014.14.4.275 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[8]. Smith LH, Dalrymple JL, Leiserowitz GS, Danielsen B, Gilbert WM, Obstetrical deliveries associated with maternal malignancy in California, 1992 through 1997Am J Obstet Gynecol 2001 184(7):1504-12.10.1067/mob.2001.114867 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[9]. Kubecek O, Laco J, Spacek J, Petera J, Kopecky J, Kubeckova A, The pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of metastatic tumours to the ovary: A comprehensive reviewClin Exp Metastasis 2017 34(5):295-307. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Al-Agha OM, Nicastri AD, An in-depth look at Krukenberg tumour: An overviewArch Pathol Lab Med 2006 130(11):1725-30.10.1043/1543-2165(2006)130[1725:AILAKT [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[11]. Gimbel IA, Mulder FI, Bosch FTM, Freund JE, Guman N, van Es N, Pulmonary embolism at autopsy in cancer patientsJ Thromb Haemost 2021 19(5):1228-35.10.1111/jth.15250 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]