Tuberculosis associated- Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (TB-IRIS) is a paradoxical deterioration or resurgence of pre-existing tuberculous lesions, or the emergence of new lesions, in individuals who are effectively undergoing anti-tuberculous treatment. This condition arises from an abnormal, excessive immune response to Mycobacterium in individuals who may, although rarely, not have Human Immunodeficiency Syndrome (HIV)-TB co-infection. This phenomenon may manifest during or even after the completion of therapy. In such cases, the initiation of concurrent steroid therapy has been found to improve symptoms by suppressing the excessive immune response. Hereby, the authors present a case report of 14-year-old teenage girl diagnosed with tuberculosis of the elbow who was started on anti-tuberculous therapy. After three months, she presented with multiple new lesions on her opposite forearm and leg. She underwent debridement of the lesions, and histopathological examination revealed a tuberculous aetiology. She was then started on concurrent steroid therapy for six weeks, following which her general condition improved, and there was no further development of new lesions.

Case Report

A 14-year-old girl presented to the Orthopaedic Department at an outside hospital with painful swelling in her right elbow, evening rises in temperature, loss of appetite, and a weight loss of approximately 10 kg over the past 4 months. She was started on a three-drug antituberculous therapy regimen: tablet isoniazid 210 mg once daily, rifampicin 320 mg once daily, and tablet pyrazinamide 750 mg once daily, based on ultrasound-guided aspiration that showed Acid Fast Bacilli. She had a history of contact with tuberculosis, as her father was recently diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis three months prior and had begun antituberculous treatment.

Over the past three months, the pain and swelling in her right elbow decreased, and she was able to perform her daily activities with minimal restrictions. However, detailed records of her follow-up from the other hospital were not available. After three months, she presented to Orthopaedic Department with painful swelling and restricted movement in her left wrist for three days.

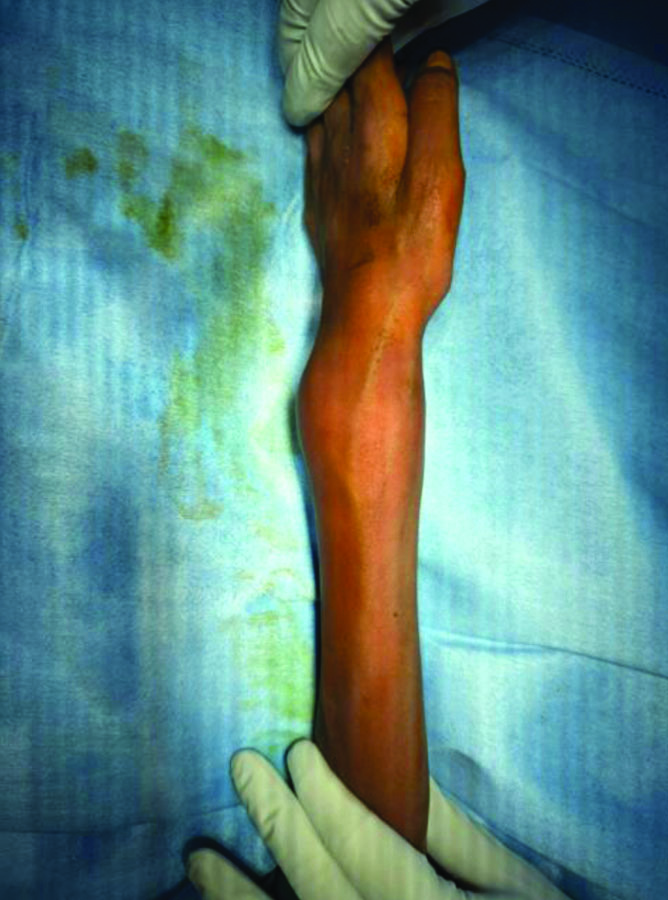

On local examination of the left wrist, there was swelling measuring 5×5 cm over the dorsal and volar aspects, with visible veins present over the swelling, associated with local warmth and tenderness [Table/Fig-1]. Both active and passive ranges of motion in the wrist were restricted due to pain. The preoperative active range of motion in the left wrist was 0-10 degrees of dorsiflexion and 0-10 degrees of palmar flexion, with no further possible passive movements. The preoperative active range of motion in the left forearm was supination of 0-45 degrees and pronation of 0-15 degrees, with no further possible passive movements. The right elbow exhibited a fixed flexion deformity of 45 degrees, with only an additional 10 degrees of active flexion possible and no further passive movement when the patient presented to our orthopaedic department.

Swelling with dilated veins seen over the distal radius.

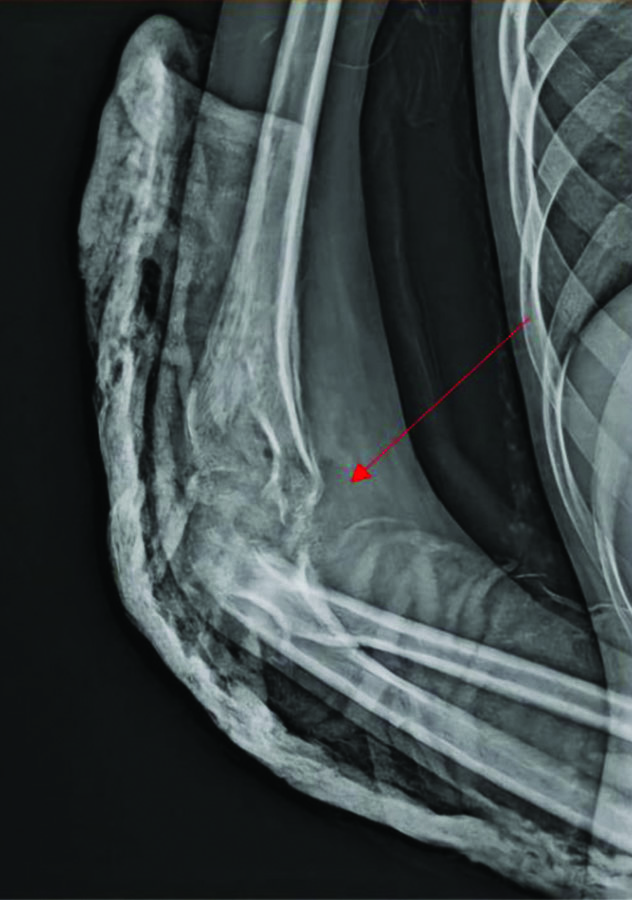

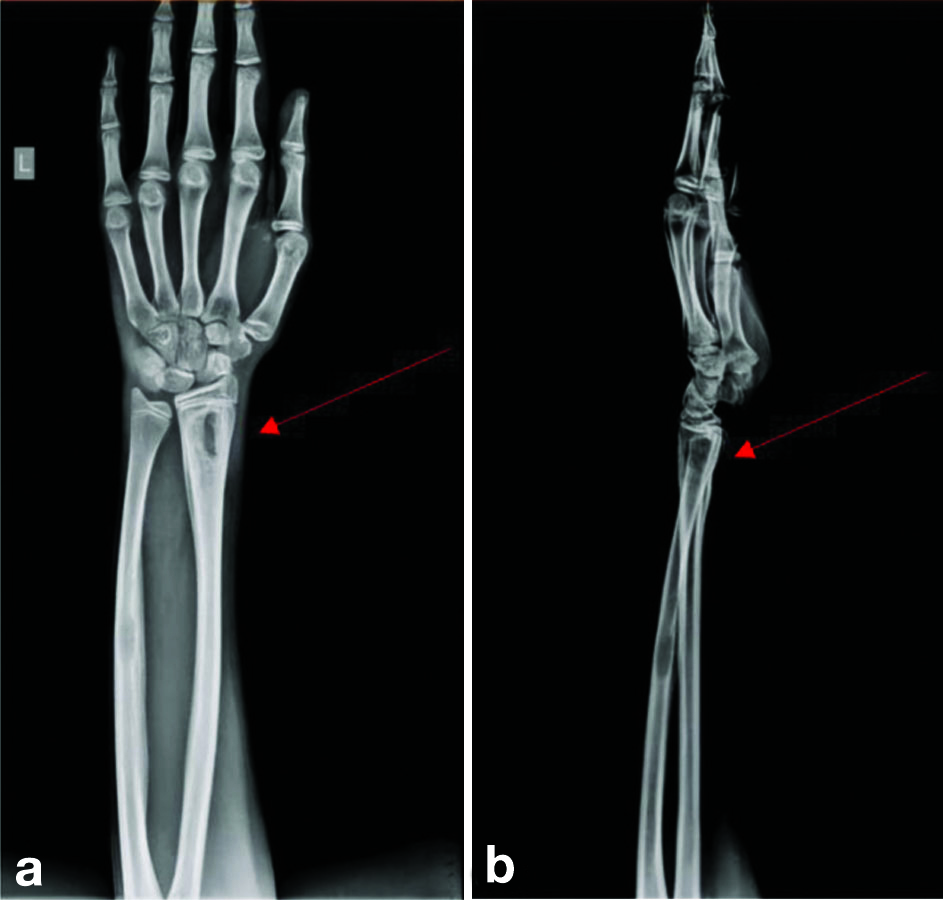

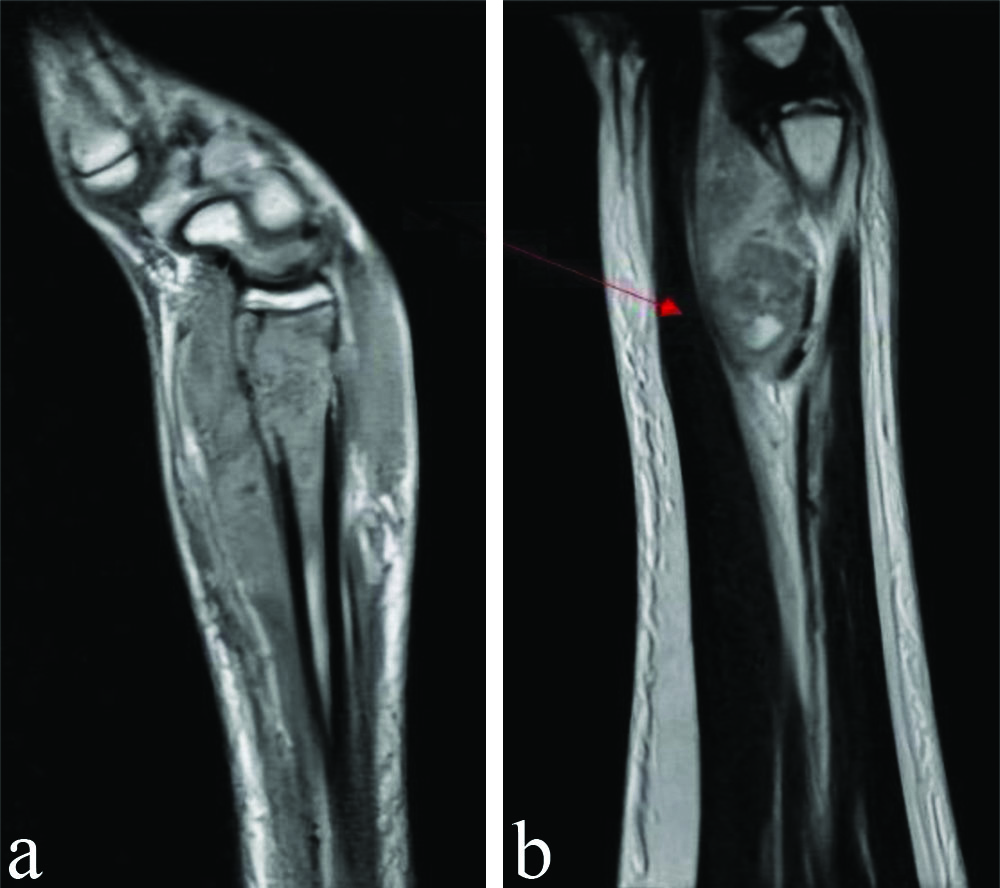

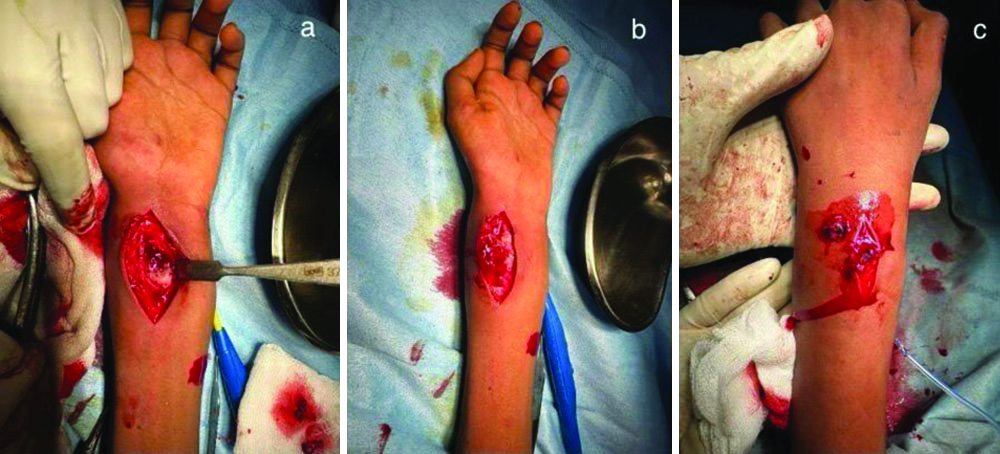

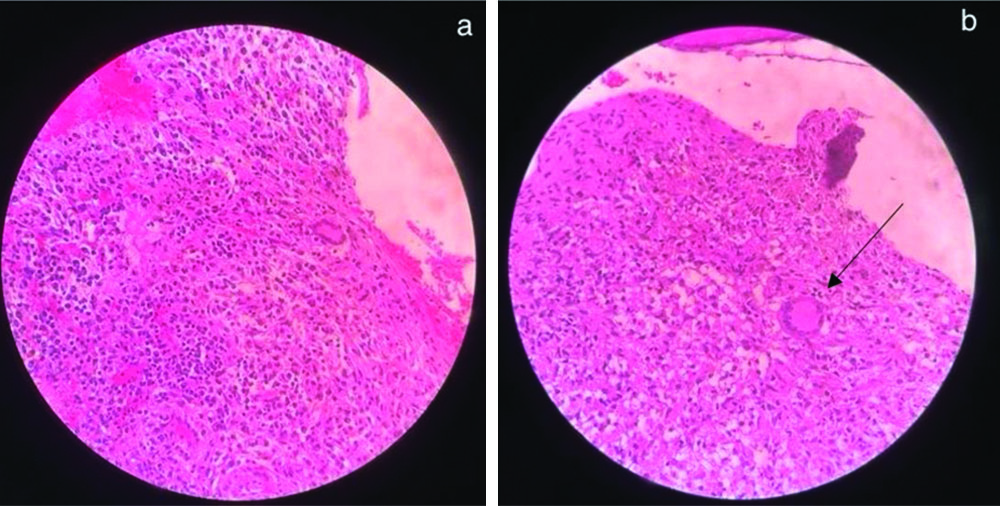

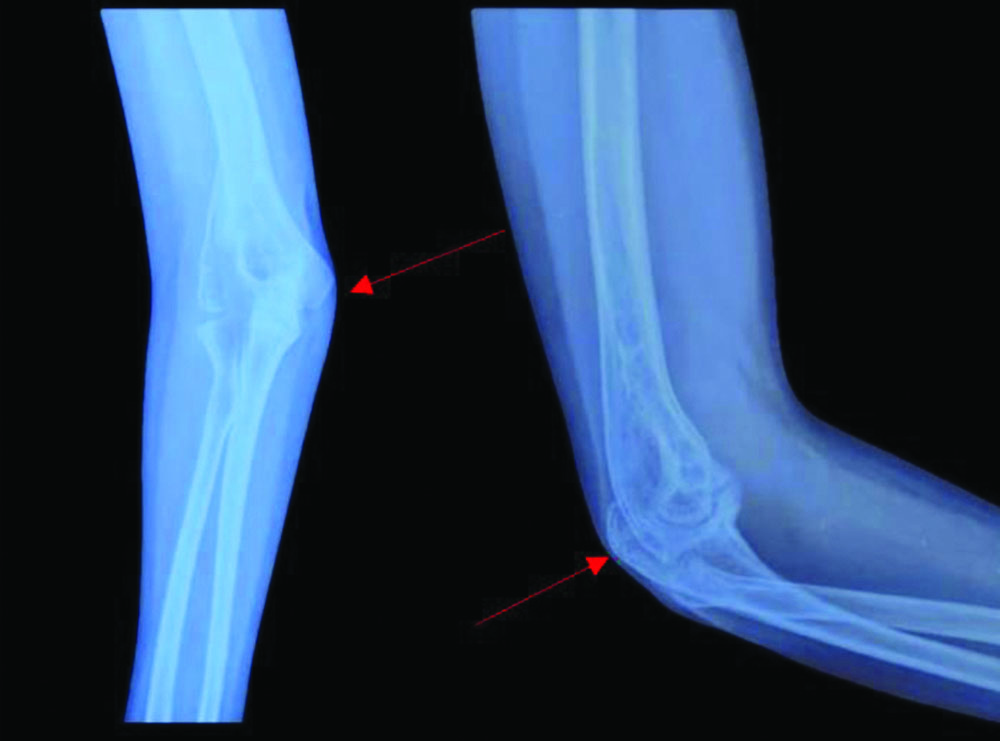

Routine laboratory investigations showed neutrophilia (78.8%) and raised inflammatory markers {Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) of 54, C-reactive Protein (CRP) greater than 130} [Table/Fig-2]. Her chest x-ray was normal. An X-ray of the right elbow taken upon presentation to our institution showed bony destruction of the articular ends and periarticular osteopenia [Table/Fig-3]. An X-ray of the left forearm and wrist revealed bony destruction in the distal end of the radius, with periosteal new bone formation, preserved wrist joint space, and a lytic lesion noted in the mid-shaft of the ulna [Table/Fig-4a,b]. The Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) showed ill-defined areas of erosion involving the meta-diaphysis of the distal radius, predominantly over the anterior aspect, extending upto the growth plate. There was a thick periosteal reaction with no intra-articular extension, and an associated adjacent soft-tissue component measuring 5.4×2.4×2.8 cm, exhibiting heterogeneous hyperintensity [Table/Fig-5a,b]. A well-defined hyperintense intra-medullary lesion measuring 2.2×0.6×0.6 cm was noted in the mid-shaft of the ulna, accompanied by diffuse cortical thickening. Computed Tomography (CT) screening revealed a partly well-defined lytic lesion measuring 1.8×1.3×1.1 cm, involving the meta-diaphyseal region of the proximal ulna, with ill-defined lytic areas and a cortical breach involving the lateral epicondyle and trochlea of the humerus. The patient underwent open debridement of the left distal radius [Table/Fig-6a-c]. The debrided sample was sent for culture sensitivity, which showed no growth. The Ziehl-Neelsen stain was negative for Acid Fast Bacilli, and GeneXpert detected Mycobacterium Tuberculosis (MTB) Complex Deoxyribonuleic Acid (DNA). Histopathological {Haematoxylin and Eosin (H&E)} examination of the debrided material revealed an ill-formed caseating epithelioid cell granuloma comprising sheets of epithelioid histiocytes and a few Langhans-type giant cells, suggestive of caseating epithelioid granulomatous inflammation with suppurative changes indicative of tuberculosis [Table/Fig-7a,b]. Her antituberculous drugs were continued.

Blood investigations of the patient taken during the time of initial presentation.

| Blood investigations | Patient values | Normal range |

|---|

| Haemoglobin | 9.8 g/dL | 10-15.5 g/dL |

| Total leukocyte count | 7480 cells/microL | 4500-11000 cells/microL |

| Differential leukocyte count | Neutrophils 78.8%Lymphocytes 15%Eosinophils 5.5%Basophils 3% | Neutrophils 40-60%Lymphocytes 20-40%Eosinophils 1-4%Basophils 0.5-1% |

| Serum albumin | 3.3 g/dL | 3.4-5.4 g/dL |

| Serum creatinine | 0.3 mg/dL | 0.4-0.9 mg/dL |

| Serum urea | 14 mg/dL | 7-20 mg/dL |

| Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) | 54 mm/hr | 0-20 mm/hr |

| C-reactive Protein (CRP) | More than 130 mg/dL | Less than 0.3 mg/dL |

X-ray of the right elbow joint with erosion of the articular surfaces of humerus and proximal ulna (taken at the time of initial presentation).

a,b) X-ray of left wrist joint and forearm (taken preoperatively) with red arrows showing lytic lesion over distal radius not involving the growth plate, a lytic lesion in the midshaft of ulna is also noted.

MRI image of left wrist joint (sagittal cut section) (taken preoperatively); a) Shows ill-defined areas of erosion in the distal radius upto the growth plate; b) The red arrow shows heterogenous hyperintensity of the adjacent soft-tissue over the anterior aspect.

Intraoperative pictures of open debridement and curettage of distal radius: a) Lytic lesion in the distal radius over the volar aspect; b) The jelly-like curetted material from distal radius; c) Debrided material from the soft-tissue lesion as suggested in MRI above.

a) Shows sheet of epithelioid histocytes (H&E, 40X); b) the black arrow shows Langhan’s type giant cell (H&E, 40X).

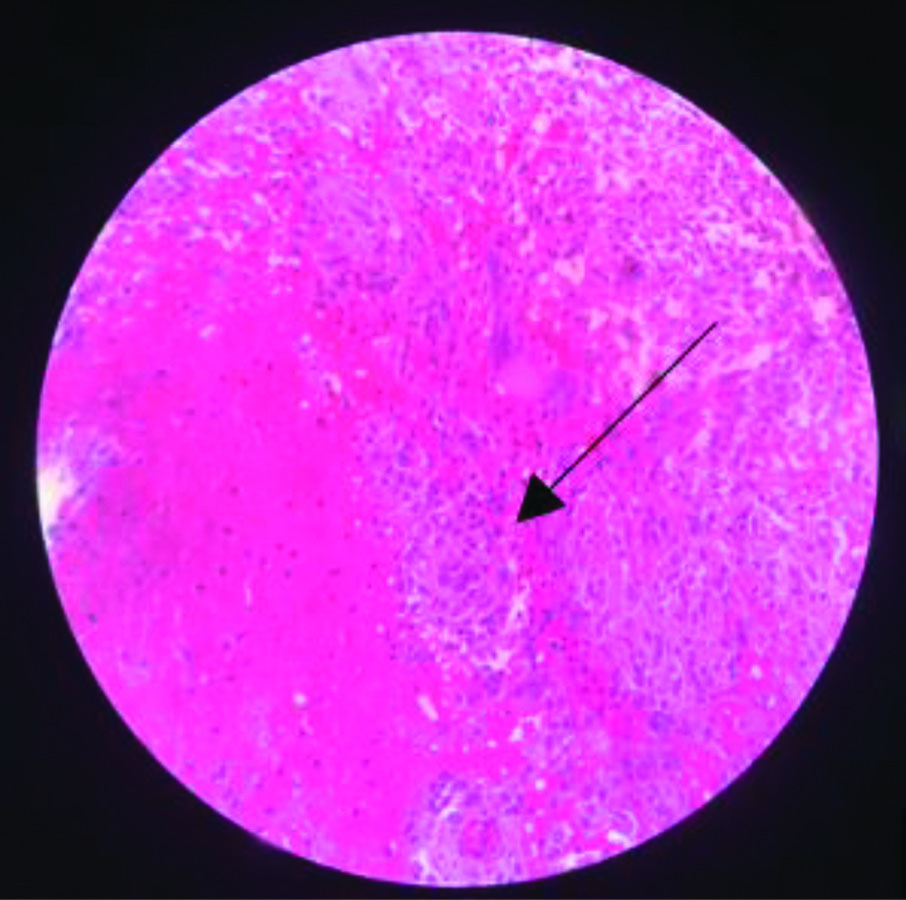

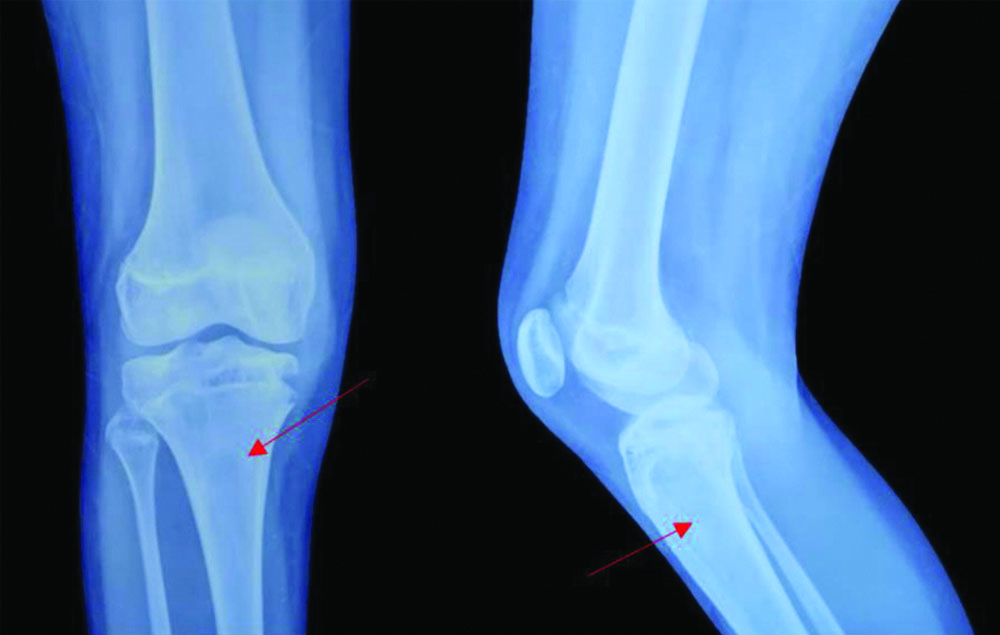

Two weeks postoperatively, she developed pain and swelling in the upper third of her right leg. The active range of motion of the right knee was 0-135 degrees of flexion, with no further possible passive movement. An X-ray of the right leg showed a lytic lesion at the proximal end of the tibia [Table/Fig-8]. An ultrasound of the right leg revealed a poorly defined thick-walled multilobulated collection with minimal internal echoes within the subcutaneous and intermuscular planes in the infra-patellar soft-tissue region, measuring 4.9×3.5 cm, overlying the proximal tibia, with increased vascularity of the soft-tissues. She was taken up for open debridement of the right leg. The debrided material sent for culture sensitivity showed no growth. The Ziehl-Neelsen stain was negative for Acid Fast Bacilli, and Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) detected MTB Complex DNA. Histopathological examination of the debrided sample showed a typical tuberculous granuloma with giant cells [Table/Fig-9]. As her condition flared up in other regions despite being on antituberculous drugs- tablet isoniazid 210 mg once daily, rifampicin 320 mg once daily, and tablet pyrazinamide 750 mg once daily- she was suspected to have IRIS. Authors also considered malignancies, opportunistic bacterial infections, drug resistance, and HIV co-infection as differential diagnoses; however, blood cultures were negative for any bacterial growth. She did not have any enlarged lymph nodes that would suggest possible malignancies similar to TB-IRIS, and she tested negative for HIV. After ruling out other differential diagnoses, authors concluded that she has TB-IRIS and concurrently started her on tablet Prednisolone 10 mg once daily for four weeks, which was subsequently tapered to 5 mg once daily for another four weeks. She was followed-up every two weeks after starting concurrent steroid therapy for upto six months. At the end of the 2-month course of concurrent steroid therapy, she showed clinical improvement, with a weight gain of 12 kg, improved appetite, and no development of any new lesions. Inflammatory markers such as Erthrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) and CRP were within the normal range at the end of the two months of concurrent steroid therapy [Table/Fig-10]. The range of motion in the right elbow, left wrist, and right knee also improved within two months [Table/Fig-11,12]. X-rays of the affected sites at the one-year follow-up showed no new lesions [Table/Fig-13,14 and 15].

X-ray of right knee joint lateral view (taken pre-operatively) with the red arrow showing lytic lesion over the proximal tibia.

Tuberculous granuloma (H&E, 40X).

Trend of C-reactive protein and Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR).

| Duration | C-reactive Protein (CRP) | Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) |

|---|

| At initial presentation | More than 130 mg/dL | 54 mm/hr |

| Postoperative 2 weeks | 118 mg/dL | 47 mm/hr |

| After starting steroid therapy |

| 2 weeks | 45 mg/dL | 25 mm/hr |

| 4 weeks | 0.2 mg/dL | 15 mm/hr |

| 6 weeks | 0.2 mg/dL | 10 mm/hr |

| 8 weeks | 0.1 mg/dL | 9 mm/hr |

Improvement in the range of movements at the end of two months of concurrent steroid therapy with antituberculous drugs; a,b) Shows the range of movements of the right elbow joint; c,d) Shows the range of movement of supination and pronation on comparing both forearms; e,f) Shows range of movements of left wrist joint; g,h) Shows comparison of alignment of both knee joints on standing; i,j) Shows range of movement of right knee joint.

Preoperative and postoperative range of movements of the involved sites.

| Involved site | Preoperative range of movement | Postoperative range of movement |

|---|

| Active | Further passive | Active | Further passive |

| Right elbow | 45-55 degree | Nil | 40-70 degree | 10 degree of flexion and extension (30-80 degree passively) |

| Left wrist | 0-10 degree dorsiflexion | Nil | 0-35 degree dorsiflexion | 10 degree |

| 0-10 degree palmarflexion | Nil | 0-15 degree palmarflexion | Nil |

| Left forearm | 0-45 degree supination | Nil | 0-45 degree supination | 5 degree |

| 0-15 degree pronation | Nil | 0-90 degree pronation | Nil |

| Right knee | 0-135 degree | Nil | 0-140 degree | Nil |

X-ray of the right elbow joint at one year of follow-up with well-defined articular margins and improvement of juxta-articular osteopenia.

X-ray of the left wrist joint at one-year follow-up with the resolved lytic lesion of the distal radius and shaft of ulna.

X-ray of the right knee joint at 1-year of follow-up with resolved lytic lesion of the proximal tibia.

Discussion

India accounts for 28% of the global tuberculosis burden, with children representing 11% of cases worldwide as of 2021. Among the TB population, 6.7% have HIV co-infection [1]. TB-IRIS (Tuberculosis IRIS) is often observed in HIV-infected patients, while in those who are HIV-negative there is an incidence rate of 10% [2]. TB-IRIS typically resolves on its own within 2-3 months, but its severity can vary. Paradoxical TB-IRIS is less common in children due to the paucibacillary nature of TB in this age group [3,4]. The primary cause of TB-IRIS is the immune response to TB infection, particularly in patients starting Antitubercular Treatment (ATT). Risk factors include a low Cluster of Differentiation 4 (CD)4 count, disseminated TB, young age, male sex, lymphopenia, anemia, hilar lymphadenopathy, and untreated suspected TB.

In both HIV-infected and uninfected patients, the initial immunopathogenesis of TB-IRIS involves myeloid cells of the innate immune system, increased expression of Th2 pathway genes, interferon regulatory factor 4, and plasma Matrix Metalloprotein (MMP)-8, which lead to tissue damage and subsequent activation of Interleukins IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, p40, Tumour Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), and interferon gamma-induced protein 10 (IP-10) [3,5,6]. This causes hypercytokinaemia that drives the inflammatory response seen in TB-IRIS. Mahomed N and Reubenson G noted that children with TB-IRIS often present with respiratory difficulty, abdominal pain, or neurological symptoms such as seizures and meningitis [4]. However, Lanzafame M and Vento S, observed other clinical signs, including recurrent fever, enlarged lymph nodes, worsening dyspnoea, and new lesions at various sites [7]. In rare cases, as observed in present patient, multiple skeletal involvements can occur without pulmonary or neurological symptoms and can be debilitating.

The diagnosis of TB-IRIS involves recognising the decline or progression of TB symptoms, clinical and laboratory findings that exclude other infections or conditions, and evidence of response to ATT. Diagnostic criteria include the absence of TB relapse, as indicated by negative mycobacterial growth in Gram stains or Ziehl-Neelsen staining, and the exclusion of other pathogens and drug hypersensitivity [2]. In present case study, the above-mentioned criteria were fulfilled before concluding that the patient had TB-IRIS.

Management of TB-IRIS is challenging due to limited evidence. Corticosteroids, such as prednisolone, given at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg/day tapered over four weeks, have been shown to reduce major cytokines and CRP levels by the second week [8]. In present case study, we repeated the CRP and ESR levels every two weeks until the completion of the steroid therapy at the eighth week. Authors observed a declining trend, which normalised by the end of one month [Table/Fig-10]. Extended steroid therapy may be necessary to prevent the recurrence of symptoms. A previously reported case involved a 19-year-old HIV-negative postpartum female who developed TB-IRIS in the vertebrae after one month on ATT for disseminated tuberculosis. She showed improvement with concurrent steroids given for three months [9]. In contrast, present patient exhibited signs of TB-IRIS in the long bones after three months of treatment with ATT for skeletal tuberculosis and improved with concurrent steroids administered for one month. Studies indicate that patients typically experience rapid symptom improvement and reduced hospital stays [7]. The present patient presented with debilitating pain that was resistant to all analgesics. However, after initiating steroid therapy, her pain significantly reduced, allowing her to be discharged within a week due to improved symptoms.

The TB-IRIS can be misdiagnosed as superimposed bacterial, viral, or fungal infections, non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections, drug resistance, poor adherence to ATT, treatment failure, relapse, or malignancies such as lymphoma or Kaposi’s sarcoma. Thus, the diagnostic criteria are essential [3,6,7,10]. A thorough investigation is required to differentiate TB-IRIS from these conditions. The prognosis of TB-IRIS varies with severity and response to treatment. Most cases are self-limiting and resolve within two to three months. Complications of TB-IRIS can arise from delayed or incorrect diagnosis, leading to prolonged illness or severe inflammation. Additionally, complications due to prolonged steroid therapy are a concern. Recent studies suggest that immunomodulators, such as thalidomide, TNF-α inhibitors, IL-6 blockers, montelukast, hydroxychloroquine, azathioprine, and pentoxifylline, might be effective alternatives to minimise prolonged steroid use, particularly in patients who are refractory to steroid therapy [10].

A case report of two HIV-negative patients (a 53-year-old and a 19-year-old) with tuberculosis of the central nervous system, who experienced worsening neurological symptoms refractory to concurrent steroid therapy with ATT, showed improvement with the addition of infliximab (an anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody) to dexamethasone (the steroid of choice in the study) [11]. However, present patient showed improvement with the addition of steroid therapy alone to ATT for her musculoskeletal symptoms; hence, an immunomodulator was not necessary.

Conclusion(s)

Tuberculosis-associated IRIS (TB-IRIS) can present in various ways, making diagnosis challenging. It is often a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, further research is needed to identify reliable biomarkers for early and accurate diagnosis. Concurrent steroid therapy with antitubercular drugs has been found to be effective in patients with TB-IRIS. However, prolonged steroid use can lead to adverse effects, necessitating the exploration of alternative treatments such as immunomodulators.

[1]. World Health OrganizationGlobal tuberculosis report 2022 Oct 27 [cited 2024 Apr 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2022 [Google Scholar]

[2]. Michailidis C, Pozniak AL, Mandalia S, Basnayake S, Nelson MR, Gazzard BG, Clinical characteristics of IRIS syndrome in patients with HIV and tuberculosisAntivir Ther 2005 10(3):417-22.10.1177/135965350501000303 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[3]. Walker NF, Stek C, Wasserman S, Wilkinson RJ, Meintjes G, The tuberculosis-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome: Recent advances in clinical and pathogenesis researchCurr Opin HIV AIDS 2018 13(6):512-21.10.1097/COH.0000000000000502 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[4]. Mahomed N, Reubenson G, Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in childrenSA J Radiol 2017 21(2):125710.4102/sajr.v21i2.1257 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[5]. Cevaal PM, Bekker LG, Hermans S, TB-IRIS pathogenesis and new strategies for intervention: Insights from related inflammatory disordersTuberculosis (Edinb) 2019 118:10186310.1016/j.tube.2019.101863 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[6]. Quinn CM, Poplin V, Kasibante J, Yuquimpo K, Gakuru J, Cresswell FV, Tuberculosis IRIS: Pathogenesis, presentation, and management across the spectrum of diseaseLife (Basel) 2020 10(11):26210.3390/life10110262 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[7]. Lanzafame M, Vento S, Tuberculosis-immune reconstitution inflammatory syndromeJ Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis 2016 3:06-09.10.1016/j.jctube.2016.03.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[8]. Meintjes G, Skolimowska KH, Wilkinson KA, Matthews K, Tadokera R, Conesa-Botella A, Corticosteroid-modulated immune activation in the tuberculosis immune reconstitution inflammatory syndromeAm J Respir Crit Care Med 2012 186(4):369-77.10.1164/rccm.201201-0094OC [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[9]. Yadav P, Bari MA, Yadav S, Khan AH, Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome following disseminated TB with cerebral venous thrombosis in HIV-negative women during their postpartum period: A case reportAnn Med Surg (Lond) 2023 85(5):1932-39.10.1097/MS9.0000000000000446 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[10]. Meintjes G, Scriven J, Marais S, Management of the immune reconstitution inflammatory syndromeCurr HIV/AIDS Rep 2012 9(3):238-50.10.1007/s11904-012-0129-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[11]. Santin M, Escrich C, Majòs C, Llaberia M, Grijota MD, Grau I, Tumour necrosis factor antagonists for paradoxical inflammatory reactions in the central nervous system tuberculosis: Case report and reviewMedicine (Baltimore) 2020 99(43):e2262610.1097/MD.0000000000022626 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]