Arnold Chiari Malformation (ACM) is a group of deformities of the cranium and hindbrain, where there is herniation of cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum. Based on the morphology and degree of anatomic defects, Chiari malformations are categorised as type 1, 2, and 3, usually through imaging. While type 2 and 3 are more prevalent and occur in younger age groups, being present from birth, type 1 Chiari is the least severe and is more frequently found in adults. Numerous deformities, including spinal deformity, encephalocele, hydrocephalus, syrinx, and elevated intracranial pressure, are associated with it. Additionally, there are autonomic disturbances associated with it as well. As a result of all these factors, anaesthesiologists face significant challenges. Hereby, the authors present a case report of 52-year-old male patient of ACM type 1 associated with bony deformity at the craniovertebral junction and syrinx, who underwent cervical decompression with C1-C2 fixation. This patient had a tingling sensation and numbness in the left upper limb, with power in the left upper limb being 1/5 and progressive gait abnormalities. Additionally, the present patient had his right upper limb amputated below the elbow joint after a road traffic accident 10 years ago, which imposed more challenges regarding intravenous access. A well-thought-out, multidisciplinary approach is needed for its management. The management of adequate intraoperative anaesthesia in such cases will have an impact on the recovery after surgery of patients with ACM type 1.

Case Report

A 52-year-old male presented with complaints of tingling and numbness in the left upper limb, which gradually developed over the past ten years. He experienced weakness in the left upper limb for the last two years, rated at 1/5 in power. Two-month-ago, he had a fall which led to progressive gait abnormalities. He denied any history of blurred vision, tinnitus, or occipital headaches.

The patient had a history of an accident 10 years ago, resulting in the amputation of his right upper limb below the elbow joint [Table/Fig-1]. The amputation was performed under general anaesthesia without any complications. The patient has no other known co-morbidities and reports no history of alcohol consumption, smoking, or drug abuse.

Preoperative picture of the patient showing severe short neck and amputated right upper limb.

On neurological examination, the power in the left upper limb was 1/5 with decreased sensory response, delayed response to pain and pressure sensation, while the right upper limb examination was normal. The power in both lower limbs was 4/5 with intact motor and sensory responses. General examination revealed a pulse rate of 80 beats per minute, regular rhythm, blood pressure of 120/70 mmHg, capillary refill time of >2 seconds, and normal cardiovascular and respiratory system findings. Airway examination showed Mallampati class III, an inter incisor distance of 3 cm, thyromental distance of 6 cm, short neck, and severe limitation of cervical spine mobilisation.

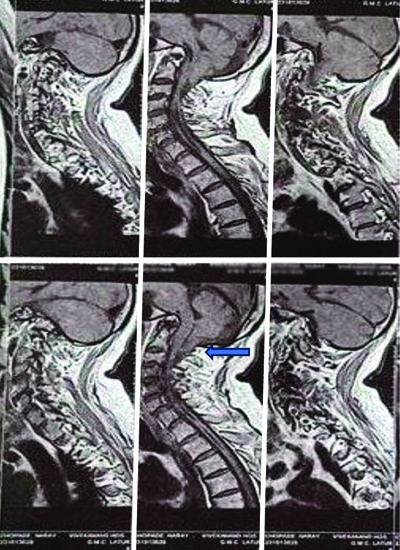

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) brain showed an inferior herniation of the cerebellar tonsil suggestive of Arnold Chiari syndrome [Table/Fig-2], with a linear hypodensity seen in the cervical and upper thoracic spinal cord suggestive of syrinx. MRI of the brachial plexus was normal, while MRI of the cervical spine revealed Atlanto-occipital assimilation, Basilar invagination, and posterosuperior dislocation of the dens compromising the foramen magnum. A 2D echocardiography showed a 60% ejection fraction, mild tricuspid regurgitation, and mild pulmonary artery hypertension. The Electrocardiogram (ECG) showed normal sinus rhythm, and the chest X-ray was normal.

MRI showing downward herniation of the cerebellar tonsils through the foramen magnum (arrow mark) suggesting ACM 1.

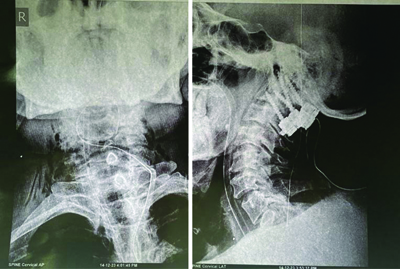

Authors anaesthetic concerns included a difficult airway, prone position with head elevation, risk of autonomic dysfunction, bleeding, postoperative pain management, and the risk of further neurological deterioration. The patient underwent cervical decompression and C1-C2 fixation (transfacetal screw at C1-C2 with rod fixation) in a prone position for atlanto-occipital assimilation at the Institute [Table/Fig-3]. Pre-emptive analgesia was achieved with Inj. Paracetamol 15 mg/kg and Inj. Dexamethasone 0.1 mg/kg. Topicalisation of the upper airway with lignocaine was performed preoperatively. A difficult airway cart and emergency drugs were prepared. Since, the fibreoptic was under repair and unavailable at the time, the plan was to perform a laryngoscopy, assess the vocal cords, determine the Cormack-Lehane grade, and then proceed with intubation using a C-MAC (video-laryngoscope) device.

Postoperative X-ray neck film showing C1-C2 fixation.

Large bore i.v. cannula was secured under all aseptic precautions. In the operating theatre, monitors with pulse oximetry, non invasive blood pressure, capnography, Bispectral Index (BIS), and a nasal temperature probe were connected. Preoxygenation was done, and the patient was pre-medicated with Inj. midazolam 0.05 mg/kg i.v., Inj. glycopyrrolate 0.004 mg/kg, Inj. fentanyl 50 mcg (0.75 mg/kg), then Inj. propofol 50 mg (0.75 mg/kg) i.v. was given. On laryngoscopy using C-MAC device revealed Cormack-Lehane grade 2b.Inj. propofol 50 mg+Inj. fentanyl 50 mcg i.v. was repeated, and after confirmation of adequate ventilation, Inj. vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg i.v. was given. Intubation was attempted with a C-MAC blade size 4, Armoured Endotracheal Tube (ETT) size 8 was rail-roaded over the gum elastic bougie. The patient was connected to the ventilator, and a capnograph was present. Bilateral air entry was equal on auscultation. The patient was maintained on sevoflurane and oxygen: air 50:50 ratio to maintain a Minimum Alveolar Concentration (MAC) of one. After a positive modified Allen’s test, an invasive radial arterial line was secured blindly under all aseptic precautions. Under ultrasound guidance, a central line was secured in the right subclavian vein after taking all necessary aseptic precautions and was connected to a Central Venous Pressure (CVP) transducer.

Inj. ceftriaxone 10 mg/kg was used for surgical prophylaxis. A Foley’s catheter was placed to monitor urine output. Vecuronium was used to maintain muscle relaxation, and neuromuscular monitoring was done. The patient was shifted to the surgical table in the prone position. All pressure points were taken care of, especially for the eyes. After proning, appropriate padding of the eyes (lubricant drops to eyes were added before proning, made sure to regularly check the position and integrity of eyes), chest, axilla, and bony prominences like the elbow were given, along with a horse-shaped gel pad with a mirror for the head, bolsters below the chest and pelvic bone were done. The abdomen was kept free, airway pressures were checked, and bilateral air entry was reconfirmed. The patient was covered with a warming blanket. Inj. methylprednisolone 15 mg/kg i.v. was given over a period of one hour. During dissection, blood loss was around 1500 mL, which was replaced with two units of Packed Red Blood Cells (PRBCs). Inj. tranexamic acid 10 mg/kg i.v. was given, and Inj. morphine 0.1 mg/kg i.v. was used for intraoperative analgesia. Inj. ondansetron 0.1 mg/kg was used to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting. Serial arterial blood gas analyses were done. For a short duration, Inj. phenylephrine 1.5 mcg/kg was given to maintain blood pressure, but after the 2nd unit of blood transfusion, blood pressure was quite stable.

After shifting the patient back to the supine position, adequate suctioning was done, and reversal was done with Inj. neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and Inj. glycopyrrolate 0.008 mg/kg when the Train-of-Four (TOF) ratio was >0.9 at the end of surgery. Extubation was commenced once spontaneous breathing was achieved, and BIS values had reached 80. Immediately after extubation, the patient was following commands. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit for further monitoring and observation. The postoperative power of the left upper limb returned to 4/5 on postoperative day 2. The postoperative recovery was uneventful, and the patient was discharged home 14 days postsurgery.

Discussion

A group of abnormalities affecting the posterior fossa and hindbrain, which includes the cerebellum, pons, and medulla oblongata, are referred to as ACM. These malformations result in complications that range from the absence of the cerebellum to cerebellar tonsillar herniation via the foramen magnum. They can be with or without other related intracranial or extracranial defects like hydrocephalus, encephalocele, syrinx, or spinal dysraphism [1-3]. Based on the morphology and degree of anatomic defects, Chiari malformations are categorised as type 1, 2, and 3, usually through imaging. While type 2 and 3 are more prevalent and occur in younger age groups and are present from birth, type 1 Chiari is the least severe and is more frequently found in adults. In type 1, the cerebellar tonsils are pointed and not rounded, and they protrude 5 mm below the foramen magnum [4].

The prevalence of ACM I is in the range of one per 1000 births [5]. Other conditions that are usually associated with ACM type I include abnormal spine curvature, tethered spinal cord syndrome, hydrocephalus, syringomyelia, and connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. The present case was ACM I, which was associated with an abnormality at the cranio-vertebral junction. The ACM I diagnosis is determined by patient history, neurological examination, and MRI [6]. MRI is the diagnostic test of choice [7]. Syringomyelia, an obstruction of the cerebrospinal fluid outflow, and direct compression of neurological structures against the surrounding foramen magnum and spinal canal can all result in neurologic signs and symptoms. The most typical presentation of Chiari I malformation is suboccipital headaches and/or cervical pain. Ocular abnormalities, vertigo, hearing loss, dizziness, ataxia of gait, and generalised fatigue are other frequent presentations. During the perioperative phase, haemodynamic instability, hypotension, hypoxia, and hypercarbia can be caused by autonomic dysfunction, which is associated with ACM type 1 [7].

Anaesthesiologists dealing with ACM type I face a number of difficulties, including: 1) airway obstruction from skeletal deformity at the cranio-vertebral junction; 2) autonomic disturbance; 3) aberrant reaction to neuromuscular blocking agents; and 4) elevated intracranial pressure. The aim of anaesthetic management is to address each of these aspects of the syndrome [6]. Gruffi TR et al., conducted a retrospective study on the management of anaesthesia in parturients with ACM type 1. The results imply that, regardless of anaesthetic management, anaesthetic complications occur infrequently in patients with ACM-I. It implies that in this population, an individual anaesthetic approach produces beneficial outcomes [8]. In present case, the anticipated challenges were a difficult airway due to atlanto-axial fusion and limitation of neck movement. Peripheral intravenous access and securing an arterial line were also a challenge since, the patient’s right upper limb was amputated below the elbow joint. Checking the modified Allen’s test before securing the arterial line is of utmost importance to check the collateral circulation of the distal limb. In ACM I, autonomic dysfunction is widely acknowledged and manifests as haemodynamic instability, hypoxia, hypercarbia, and hypotension both during and after surgery. Therefore, authors prepared invasive arterial blood pressure monitoring on the left side, arterial blood gas analysis for correction, and a right subclavian central venous catheter. Airtraq TM laryngoscope or fiberoptic bronchoscopic intubation, C-MAC intubation instead of standard laryngoscope, is recommended in patients with cervical spine abnormalities [7,9]. The present patient had severe cervical spine immobilisation and therefore was intubated with C-MAC assistance with the help of a bougie. Similarly, in a case done by Mago V et al., the patient had scoliosis and a limitation of neck extension; hence, they had performed video laryngoscope-aided intubation [6]. Care should be taken to avoid a rise in intracranial pressure which can be caused by induction, intubation, positioning, and extubation [10]. A case study by Coviello A et al., on a patient with ACM type 1, who underwent general anaesthesia for a hip prosthesis procedure. The patient experienced many episodes of apnoea and desaturation during awakening. Hypertensive episodes, nausea, and general malaise complicated the awakening process. For the next 48 hours, a Post Anaesthesiology Care Unit (PACU) was necessary [11]. Normocapnia via capnography and ABG analysis was maintained throughout the procedure with a peak airway pressure of 25 mmHg. These patients have an increased sensitivity to neuromuscular blocking agents [9,12]. Authors used vecuronium for induction since, succinylcholine shouldn’t be used to facilitate rapid intubation, to prevent an increase in intracranial pressure. Monitoring of neuromuscular function with TOF is very important.

Conclusion(s)

In conclusion, there are possible anaesthetic risks related to ACM Type I and its associated disorders. Therefore, to ensure better management during surgery, a thorough preoperative examination of autonomic dysfunction should be performed, especially in cases with cervical syrinx. An interdisciplinary team led by professionals with expertise in anaesthesiology, neurology, and neurosurgery will also enhance the best possible outcome for patients.

[1]. de Arruda JA, Figueiredo E, Monteiro JL, Barbosa LM, Rodrigues C, Vasconcelos B, Orofacial clinical features in Arnold Chiari type I malformation: A case seriesJ Clin Exp Dent 2018 10(4):e378-e382.10.4317/jced.54419 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[2]. Bhimani AD, Esfahani DR, Denyer S, Chiu RG, Rosenberg D, Barks AL, Adult Chiari I Malformations: An analysis of surgical risk factors and complications using an international databaseWorld Neurosurg 2018 115:e490-e500.10.1016/j.wneu.2018.04.077 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[3]. Kandeger A, Guler HA, Egilmez U, Guler O, Major depressive disorder comorbid severe hydrocephalus caused by Arnold-Chiari malformationIndian J Psychiatry 2017 59(4):520-21.10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_225_17 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[4]. Hidalgo JA, Tork CA, Varacallo M, Arnold-Chiari MalformationStatPearls 2024 Treasure Island (FL)StatPearls Publishing28613730 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

[5]. Khatib MY, Elshafei MS, Shabana AM, Mutkule DP, Chengamaraju D, Kannappilly N, Arnold-Chiari malformation type 1 as an unusual cause of acute respiratory failure: A case reportClin Case Rep 2020 8(10):1943-46.PMCID: PMC756286810.1002/ccr3.304333088525 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Mago V, Chakole V, Nisal R, Umate R, A case of anaesthetic management of Arnold-Chiari Malformation I: A contest to anaesthesiologistsCureus 2023 15(1):e33848PMCID: PMC993221810.7759/cureus.3384836819310 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Strahle J, Muraszko KM, Kapurch J, Bapuraj JR, Garton HJ, Maher CO, Chiari malformation Type I and syrinx in children undergoing magnetic resonance imagingJ Neurosurg Pediatr 2011 8(2):205-13.10.3171/2011.5.PEDS112121806364 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Gruffi TR, Peralta FM, Thakkar MS, Arif A, Anderson RF, Orlando B, Anaesthetic management of parturients with Arnold Chiari malformation-I: A multicenter retrospective studyInt J Obstet Anaesth 2019 37:52-56.10.1016/j.ijoa.2018.10.00230414718 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Mustapha B, Chkoura K, Elhassani M, Ahtil R, Azendour H, Kamili ND, Difficult intubation in a parturient with syringomyelia and Arnold-Chiari malformation: Use of Airtraq laryngoscopeSaudi J Anaesth 2011 5(4):419-22.PMCID: PMC322731410.4103/1658-354X.8727422144932 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Nel MR, Robson V, Robinson PN, Extradural anaesthesia for caesarean section in a patient with syringomyelia and Chiari type I anomalyBr J Anaesth 1998 80(4):512-15.10.1093/bja/80.4.5129640161 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. Coviello A, Golino L, Posillipo C, Marra A, Tognù A, Servillo G, Anaesthetic management in a patient with Arnold-Chiari malformation type 1,5: A case reportClin Case Rep 2022 10(2):e05194PMCID: PMC881528110.1002/ccr3.519435140940 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[12]. Agustí M, Adàlia R, Fernández C, Gomar C, Anaesthesia for caesarean section in a patient with syringomyelia and Arnold-Chiari type I malformationInt J Obstet Anaesth 2004 13(2):114-16.10.1016/j.ijoa.2003.09.00515321417 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]