Introduction

There is strong epidemiological evidence of an increased risk of developing neuropsychiatric disorders following childhood exposure to Group A Beta-haemolytic Streptococci (GABHS) infections, such as sore throat and scarlet fever. Neurological manifestations can include Sydenham’s Chorea (SC), changes in motor skills and coordination, myoclonus, dystonia, and Parkinson’s disease. Psychiatric symptoms may involve the onset or worsening of Obsessive-compulsive Disorder (OCD), Tourette’s Syndrome (TS), tic disorders, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and Paediatric onset Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) [1-4]. In the landmark treatise “Chorea and Choreiform Affections” (1894), Sir William Osler first described obsessive-compulsive behaviour in SC, which was further established in a larger case series by Chapman AH et al., in 1958 [5,6]. A subsequent case report of an 11-year-old boy by Kondo K and Kabasawa T demonstrated the sudden development of tics following an episode of unexplained fever, associated with elevated Anti Streptolysin O (ASO) antibody titres, and improvement with corticosteroids. This further directed the discussion on the role of biological factors in tic disorders [7].

In 1998, Swedo SE and colleagues first described the condition as PANDAS and established diagnostic criteria for it. They conducted a systematic clinical evaluation of 50 children at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) who met all five working diagnostic criteria for PANDAS [Table/Fig-1] [8].

Working diagnostic criteria for PANDAS.

| Diagnostic criteria |

|---|

| 1. Presence of OCD/or tic disorder as per DSM III-R/DSM IV |

| 2. Prepubertal symptom onset (between 3 years of age and beginning of puberty) |

| 3. Episodic course of symptom severity (abrupt onset of symptoms or by dramatic symptom exacerbation) |

| 4. Temporal association with GABHS infections (i.e., positive throat culture or elevated anti-GABHS antibody titre) |

| 5. Association with neurological abnormalities (motor hyperactivity, choreiform movements) |

Wald ER estimated the incidence of PANDAS and Paediatric Acute-onset Neuropsychiatric Syndrome (PANS) among children aged 3 to 12 years to be 1 per 11,765, with some variations [9]. Although PANDAS commonly occurs in children and adolescents, there are case reports of adults with similar presentations following a Group A Streptococcal (GAS) infection. One such case has been reported in India by Deshmukh RP et al., [10].

In India, there are very few case reports and only one case series despite the high prevalence of streptococcal infections, largely due to a lack of awareness among the public and clinicians [11-14].

Authors reported four cases in present series that fulfill almost all the criteria established by NIMH, with unique presentations of dissociative disorder and hoarding, and their association with GABHS, contributing further to the existing literature. Consent was obtained from all four patients to use their clinical information while ensuring their personal information remains confidential.

Case 1

A 16-year-old unmarried Muslim girl from a lower-class family in a rural area presented to the Psychiatry Outpatient Department (OPD) with complaints of multiple episodes of shortness of breath and unresponsiveness lasting for 1 to 2 hours, without any evidence of tongue biting or incontinence, occurring over the last 5 to 6 days. These episodes were precipitated by a conflict between her brother and his wife. During the interview, she revealed that she had repeated unwanted thoughts about her brother’s separation from his wife and was excessively worried about her nephew, particularly about what would happen to him if his parents separated, despite being repeatedly reassured. These thoughts were so disturbing to her that they triggered palpitations, breathlessness, and periods of altered consciousness with intact memory.

She was initially diagnosed with Dissociative (Conversion) Disorder after excluding all possible medical morbidities that could explain her symptoms, based on her history, clinical examination, and relevant investigations, including Electroencephalogram (EEG), Electrocardiogram (ECG), and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) of the brain, all of which were normal. Upon further inquiry, she revealed having obsessive doubts about her daily household activities, such as whether she had locked the door, turned off the gas oven, or closed the water tap properly. She would check these things multiple times to be sure, and this behaviour had persisted for the past five years. For the last 1.5 years, she had also experienced repeated thoughts about dirt contamination, leading her to wash her hands and clothes multiple times. Additionally, she reported avoiding activities in odd numbers, as she considered them to be unlucky and dangerous. These thoughts were so distressing that she tried hard to rid herself of them but failed, continuing to seek reassurance from her mother until she felt satisfied.

Her mother stated that all of her symptoms started after an episode of high-grade fever associated with chills, rigour, joint pain, and sore throat five years ago. Previous treatment reports showed raised ASO titre with a blood level of 500 IU/mL during the febrile episode, for which she was treated with Penicillin-G (400,000 IU/day) for two years. Her symptoms improved for almost three years, but she experienced an exacerbation of all her symptoms over the last 5 to 6 months following another untreated episode of fever and pain in her bilateral knees, shoulders, wrists, and metacarpophalangeal joints six months ago. She had also been suffering from small joint pain frequently over the past six months.

Her mental status examination revealed obsessions and compulsions related to thought possession, with grade 4 insight into her illness. The Childhood Yale-Brown Obsessive-compulsive Scale (C-YBOCS) [15] score was 30 on the first visit, indicative of severe OCD (ICD-11 code 6B20) with dissociative symptoms [16]. Her blood investigations showed a raised ASO titre (>300 IU/mL), elevated C-reactive Protein (CRP) (10 mg/dL), and Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) (45 mm/hour), which suggested a past streptococcal infection, along with a normal ECG and 2D echocardiography.

A diagnosis of PANDAS was made based on the sudden onset of obsessive-compulsive symptoms at a prepubertal age, with an abrupt worsening immediately following a streptococcal infection associated with a high ASO titre. She was treated in liaison with the Rheumatology Department. Tab Fluoxetine was started at a dose of 20 mg and increased to 40 mg within two weeks, along with Clonazepam (0.5 mg) at bedtime. Based on her clinical symptoms, elevated ASO titre, ESR, CRP, frequent relapses of fever, joint pain, and a past history of good response to beta-lactam antibiotics, Tab Penicillin-G was initiated at a dose of 800,000 IU/day and was advised to continue prophylactically for the next five years with periodic follow-up. After four weeks, her C-YBOCS score improved to 16, and she showed symptomatic improvement [15]. There were no further dissociative episodes. Later, in the Rheumatology Department, a rapid ASO test (latex slide test) for streptococcal infection was performed and became negative after four weeks of treatment [17].

She is currently maintaining well on Tab Fluoxetine (40 mg) and Penicillin-G (800,000 IU/day) and is followed-up every two months. During subsequent visits, she has shown significant improvement in her obsessive-compulsive symptoms without any further dissociative episodes.

Case 2

A 10-year-old boy from a rural area presented to the Psychiatry OPD with complaints of sudden jerky involuntary movements, including eyebrow movements, shoulder shrugging, blinking of the eyelids, and occasional throat clearing, which started suddenly three months ago. The severity of these movements has been increasing day by day. The movements decreased only when he engaged in activities requiring focused attention, like doing math or drawing, and they subsided during sleep.

Within a very brief period, he developed sudden utterances of obscene words without any provocation, suggestive of coprolalia or complex vocal tics. Initially, these utterances occurred 1-2 times a day but gradually increased in frequency. He refused to go to school for fear of being bullied, and his scholastic performance declined. During the interview, he stated that he felt an inner distress before the movements, with a sense of relief afterward. The movements were rapid (lasting 1-2 seconds), difficult to control, and were disturbing his daily activities and disrupting his sleep. The symptom presentations were suggestive of motor tics.

His parents reported a history of high-grade fever, rash, and sore throat occurring four weeks before the onset of these symptoms, for which he was treated by a local physician. He has also been suffering from sore throats frequently over the past year and has been on irregular medications, according to his parents.

On mental status examination, the boy’s affect was anxious, and he exhibited a decreased attention span in higher mental functions without any other psychopathology. He scored 30 on the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) [18]. A primary diagnosis of Tourette syndrome was made based on the presence of complex vocal tics and multiple motor tics with onset during childhood (ICD-11 code 8A05.00) as determined by the Psychiatry Department [16].

His work-up revealed leucocytosis, raised CRP (22 mg/dL), and a highly raised ASO titre (>800 Todd units), along with normal EEG, Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) brain, urine, and serum copper and ceruloplasmin levels. He was ultimately diagnosed with PANDAS, considering the new onset of tics following a recent streptococcal infection, as suggested by raised ASO titre and CRP. Tab Risperidone was initiated at a dose of 0.5 mg twice daily and gradually escalated to 1 mg twice daily within two weeks. He was also referred to the Paediatrics Department for further management.

A morning throat swab sample was collected aseptically from the tonsillar area and the posterior pharyngeal wall and sent to the microbiology laboratory for culture, where it was incubated on blood agar media for three days. Beta-haemolytic colonies were identified for GAS. Tab Amoxicillin + Clavulanic acid (375 mg) was prescribed twice a day for 10 days. He also underwent habit reversal therapy from the clinical psychology department.

On his next visit after four weeks, his tics had decreased, and he scored 10 on the YGTSS [18]. He was being followed-up every two months but was eventually lost to follow-up after four visits.

Case 3

A 14-year-old boy from a lower-middle-class family in a rural area was referred to the Psychiatry OPD from the general medicine OPD due to sudden onset behavioural abnormalities. These manifested as collecting unnecessary items such as broken toys, papers, and used chocolate wrappers from outside his home-specifically from the streets and dustbins-and accumulating them in his room. He has been preventing his mother from discarding these items, insisting that they might be useful in the future for the past two months. His mother sometimes found him attempting to fix the broken, useless items instead of throwing them away.

He had been visiting the medicine OPD for fever and sore throat over the past six weeks. His ASO titre was 410 IU/mL, and a throat swab culture was positive for GABHS, with elevated ESR (20 mm/hour) and CRP (30 mg/mL). After receiving treatment with amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (250/125 mg) three times daily and paracetamol for 14 days for the streptococcal infection, his fever and throat pain subsided. However, shortly thereafter, he developed these behavioural symptoms.

His symptoms were suggestive of hoarding disorder (ICD-11 code 6B24) [16], with a score of 20 on the hoarding rating scale [19] during his first visit. The CY-BOCS symptom checklist did not reveal any other symptoms except for hoarding. A final diagnosis of PANDAS (Paediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections) was made, and treatment was initiated with fluoxetine (20 mg) and clonazepam (0.5 mg), along with behavioural intervention from the clinical psychology department. The dose of fluoxetine was gradually increased to 60 mg over four weeks. However, with the increased dose, he became very restless and experienced disturbed sleep, prompting an increase in the dose of clonazepam to 0.5 mg twice daily.

He gradually began to improve after six weeks of treatment, and his score on the hoarding rating scale decreased to five. He is being followed-up regularly every four weeks in the Psychiatry department.

Case 4

A six-year-old boy from a lower middle-class family in a rural area was visiting the Psychiatry OPD for mild Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). He developed sudden-onset, frequent involuntary jerky movements of the neck and eyebrows, suggestive of a tic disorder (ICD 11 code 8A05.00) [16], over the past 6-7 months, following an episode of fever with myalgia lasting 4-5 days. He was treated conservatively with paracetamol. He was maintaining well on treatment with risperidone (0.5 mg) twice daily, but again experienced symptom exacerbation following another episode of fever lasting seven days. At this time, his Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS) score was 21 [18].

He was referred to the Paediatrics OPD for evaluation of the fever, which was examined in detail. His blood reports revealed a raised ASO titre (450 IU/mL), indicating the presence of streptococcal infection. Further investigations, including a rapid ASO test for Group A Streptococcus (GAS), were conducted, which returned reactive, suggesting a current GABHS infection [17]. This raised a high index of clinical suspicion for PANDAS.

He was treated with risperidone (1 mg) twice daily and 10 mg of fluoxetine for tics, along with appropriate management for the ongoing streptococcal infection with syrup amoxicillin (125 mg/5 mL), 5 mL three times daily for 10 days, as prescribed by the paediatric department. This treatment showed subsequent significant improvement in symptoms after six weeks, with a significant reduction in his YGTSS score to 5 [16]. He was followed-up in the Psychiatry OPD every month.

Discussion

It has been more than 20 years since the introduction of PANDAS, and despite a working diagnostic criterion laid down by the NIMH [Table/Fig-1] [8], it still remains a diagnosis of exclusion due to the lack of a better definition of clinical features, precise biological diagnostic markers, and neuroimaging to guide appropriate therapeutic protocols [20]. Clinicians have faced numerous diagnostic challenges due to the difficulties in establishing a temporal association between the sudden onset of OCD and preceding GABHS infection. This is complicated by variable lag times and an increasing number of false-negative cases due to the low sensitivity of rapid streptococcal tests [21] and throat cultures (which have a false-negative rate of 5-15%), especially given the presence of carrier states among 1 in 20 children. This issue is particularly pronounced in a country like India, where streptococcal infections are endemic.

There have also been case reports of symptom exacerbation following other infections, notably mycoplasma, Lyme disease, and Epstein Barr Virus (EBV) infection. Additionally, post-pubertal symptom onset is not uncommon. Considering all these factors, the NIMH proposed a new clinical entity called PANS, which includes acute and dramatic exacerbations of symptoms with or without the presence of a preceding infection.

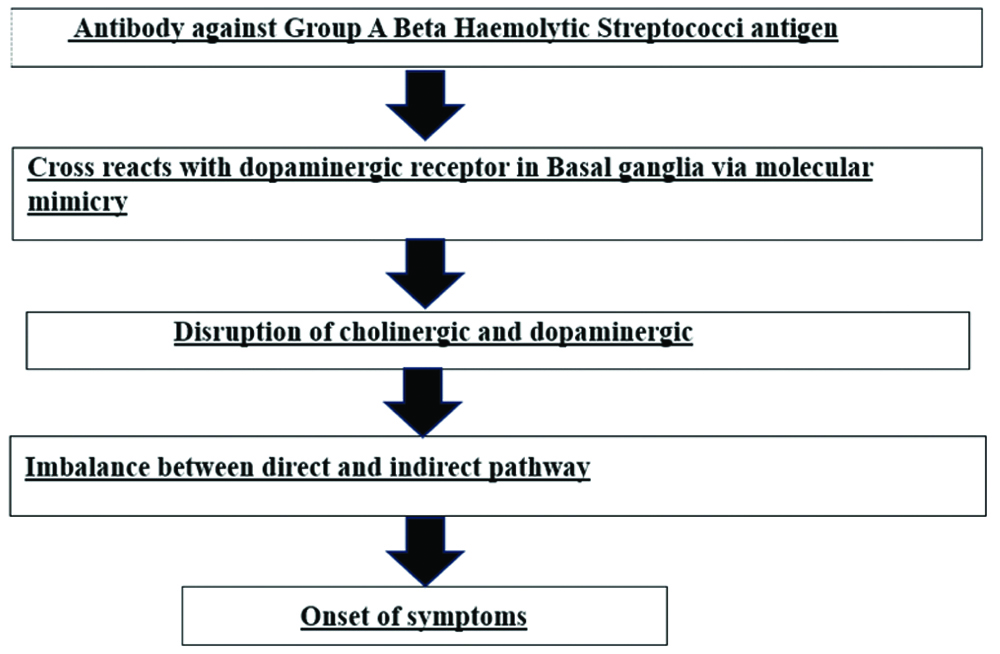

The pathophysiology behind PANDAS can be explained by specific autoantibodies targeting the dominant epitope of GABHS (N-acetyl-beta-D-Glucosamine), which influence neuronal signal transduction, resulting in behavioural alterations and movement control [22]. These autoantibodies, through molecular mimicry, eventually cross-react with antigens in the caudate nucleus, causing neuroinflammation by releasing inflammatory markers like Interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and Tumour Necrosis Factor (TNF)-alpha in the dorsal striatum. This disruption of cholinergic activity leads to an imbalance between the direct and indirect pathways within the basal ganglia, which results in the motor and behavioural symptoms of PANDAS. The pathophysiology of PNADAS has been depicted in [Table/Fig-2] [22-24].

Pathophysiology of PANDAS [22,23,24].

The involvement of certain brain areas has been described in the literature, although the findings are not very specific. A longitudinal study by Giedd JN et al., compared the MRIs of 34 patients with PANDAS to those of 84 healthy controls and found significant enlargement of the caudate, putamen, and globus pallidus. However, no correlation could be found between symptom severity and basal ganglia volume [25].

The clinical picture of PANDAS can be quite confusing and variable, making it difficult to diagnose promptly. A three-year prospective follow-up study on 12 children with PANDAS by Murphy ML and Pichichero ME found that all patients exhibited Obsessive-compulsive (OC) symptoms and became emotionally labile. Among them, most had germ or illness-related compulsive washing behaviours, while others developed hoarding, separation anxiety, recurrent tics, and one patient exhibited transient ADHD-like symptoms, including fidgeting and memory impairment [26].

The diagnosis of PANDAS can easily be confused with Sydenham’s Chorea (SC), but there are key differences, such as the latency of onset between GABHS infection and the onset of neuropsychiatric symptoms. SC typically has a history of mitral valve involvement in the majority of cases and follows a monophasic course, whereas PANDAS follows a fluctuating course [14,27].

Treatment for PANDAS is similar to that for childhood OCD or tics and consists of psychopharmacological, behavioural, and psychological interventions, but it requires special attention to the management of streptococcal infection. Psychiatric medications include Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and/or antipsychotics, which should be initiated at a very low dose with slow escalation and close monitoring. Patients with PANDAS often show a dramatic resolution of their symptoms following the administration of antibiotics like beta-lactam antibiotics, azithromycin, and clindamycin.

Some prospective studies have compared tonsillectomy and/or adenoidectomy as treatment options for recurrent PANDAS against other non-surgical measures, but these studies have failed to exhibit any significant differences [28]. Various placebo-controlled studies have reported excellent results in terms of symptom improvement with immunotherapy, like plasmapheresis, corticosteroids, and intravenous immunoglobulin, in treating childhood infection-triggered OCD or tic disorder and PANDAS. However, some other studies have failed to support these findings [29].

In India, there are no reported case series encompassing the diverse clinical presentations of PANDAS. In this paper, authors describe four cases of PANDAS that presented with distinctive clinical features [Table/Fig-3].

Summary of the four cases.

| S. No. | Age and gender | Onset of illness | Presenting psychiatric symptoms | Investigations done | Treatment received | Severity scale score over time |

|---|

| Case 1 | 16 year/female | 5 years back (at 11 years of age) | Dissociative symptoms mostly associated with distressing obsessional thought which itself was a stressor for the patient.Other OC symptoms including pathological doubt and checking, fear of dirt and contamination | ASO titre (>300 IU/mL), CRP, ESR, high CRP (10), ESR (45 mm/hr) | Tab penicillin G (4 lac IU)/dayTab fluoxetine (40 mg) | YBOCS score reduced from 30 to 16 after 4 weeks with treatment |

| Case 2 | 10 years/male | 3 months ago | Multiple motor tic, complex vocal tic suggestive of Tourette syndrome | Raised ASO Titre (>800 IU/mL), CRP (22), throat swab culture positive for GAS, elevated CRP (22), Leucocytosis | Tab Amoxicillin (250) BD for 10 days with tablet paracetamol, risperidone (1 mg) BD, habit reversal therapy | YGTSS score improved to 10 from 30 after 6 weeks of treatment |

| Case 3 | 14 years/male | 2 months back | Hoarding disorder | Raised ASO titre (410 IU/mL), positive throat swab culture for GAS, elevated ESR (20), CRP (30) | Tab amoxicillin with clavulanic acid (250 mg/125 mg) TDS for 14 days.Fluoxetine titrated upto 60 mg | Hoarding rating scale score reduced from 20 to 5 after 6 weeks of treatment |

| Case 4 | 6 years/male | 6-7 months back | Motor tic disorder along with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) | ASO titre (450 todds unit), Rapid ASO test positive | Syrup amoxicillin(125 mg/5 mL) 5 mL TDSFluoxetine (10 mg), Risperidone (1 mg) | YGTSS score reduced to 5 from 21 after 6 weeks |

The very first case presented with dissociative conversion disorder, and a retrospective interview revealed a sudden onset of OC symptoms, which abruptly exacerbated following GABHS infection. A possible case of PANDAS with conversion disorder was previously reported in 2008, where a 16-year-old boy developed sudden onset OC symptoms and motor tics, along with a gradually deteriorating course of illness that included dissociative episodes, without any preceding clear-cut clinical symptoms of streptococcal infection. Later blood investigations showed raised ASO and anti-Deoxyribonuclease (DNase) B titres. Further evaluation by a PANDAS specialist opined that these findings were consistent with PANDAS; however, there was no clear clarification as to whether the dissociative symptoms were related to the OC symptoms or PANDAS. Additionally, this case did not fully satisfy the diagnostic criteria for PANDAS in terms of post-pubertal age of onset and the lack of laboratory-documented temporal association between symptom exacerbation and streptococcal infection [30]. Another case of PANDAS with conversion was published in the literature, but a relationship between tics and conversion disorder could not be established [31].

In present case, the dissociative symptoms were closely associated with and triggered by obsessive thoughts, and there was significant improvement in the dissociative symptoms with a reduction in obsessive thoughts after treatment for OCD, further strengthening this association. The second and fourth cases presented with sudden onset Tourette syndrome and tic disorder, with co-morbid ASD, respectively, following streptococcal infection. While many cases of PANDAS with vocal and motor tics have been reported, the classical features of Tourette syndrome could not be found in present cases. The third case presented with hoarding disorder after an episode of fever with evidence of recent GAS infection.

All four cases almost fulfilled the working diagnostic criteria provided by NIMH in terms of prepubertal age of onset, waxing and waning course of illness, and abrupt initiation of symptoms after streptococcal infection, showing rapid improvement of physical and behavioural manifestations with treatment for GABHS infection. This satisfies the temporal association and cause-effect relationship between streptococcal infection and obsessive-compulsive symptoms, tics, and hoarding behaviours [Table/Fig-3]. In the only case series from India, one rare Obsessive-compulsive And Related Disorder (OCRD), specifically trichotillomania (ICD 11 code 6B25), was found in an 8-year-old girl, who was subsequently diagnosed with PANDAS [14,16]. Among our cases, authors also identified another unique OCRD symptom, hoarding disorder, which suggests that, apart from OCD or tic disorders, PANDAS can present with a spectrum of psychiatric manifestations involving the basal ganglia, which can be affected in PANDAS due to autoimmunity.

Conclusion(s)

These cases are reported to raise awareness among physicians and the public about unusual presentations of PANDAS. It is essential that all cases of streptococcal infections, manifesting as fever, rash, or arthritis, are monitored closely for the subsequent development of Obsessive-compulsive Disorder (OCD) or tic disorders. Additionally, all prepubertal cases of OCD or tic disorders should be screened retrospectively for GABHS infection. Early recognition of PANDAS will ultimately facilitate the rapid initiation of treatment, fostering collaboration between paediatric medicine, general medicine, rheumatology, and Psychiatry departments. The present approach aimed to reduce school dropout rates and improve the quality of life for school-aged children. Therefore, it is proposed to include symptoms of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders in the presentation of PANDAS within the nosological status or diagnostic criteria.

[1]. Aron AM, Freeman JM, Carter S, The natural history of Sydenham’s chorea. review of the literature and long-term evaluation with emphasis on cardiac sequelaeAm J Med 1965 38:83-95. [Google Scholar]

[2]. Williams KA, Swedo SE, Post-infectious autoimmune disorders: Sydenham’s chorea, PANDAS and beyondBrain Res 2015 1617:144-54. [Google Scholar]

[3]. Mora S, Martín-González E, Flores P, Moreno M, Neuropsychiatric consequences of childhood group A streptococcal infection: A systematic review of preclinical modelsBrain Behav Immun 2020 86:53-62. [Google Scholar]

[4]. Leslie DL, Kozma L, Martin A, Landeros A, Katsovich L, King RA, Neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infection: A case-control study among privately insured childrenJ Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008 47(10):1166-72. [Google Scholar]

[5]. Osler W, On chorea and choreiform affections [Internet] 1894 [cited 2024 Apr 2] LondonHK Lewis:182Available from: https://archive.org/details/onchoreachoreifo00oslerich [Google Scholar]

[6]. Chapman AH, Pilkey L, Gibbons MJ, A psychosomatic study of eight children with Sydenham’s choreaPaediatrics 1958 21(4):582-95. [Google Scholar]

[7]. Kondo K, Kabasawa T, Improvement in gilles de la tourette syndrome after corticosteroid therapyAnn Neurol 1978 4(4):387-87. [Google Scholar]

[8]. Swedo SE, Leonard HL, Garvey M, Mittleman B, Allen AJ, Perlmutter S, Paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections: Clinical description of the first 50 casesAm J Psychiatry 1998 155(2):264-71. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Wald ER, A paediatric infectious disease perspective on paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with streptococcal infection and paediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndromePediatr Infect Dis J 2019 38(7):706-09. [Google Scholar]

[10]. Deshmukh RP, Mane AB, Singh S, PANDAS in an adult?: A case reportInd J Priv Psychiatry 2022 16(1):44-45. [Google Scholar]

[11]. Srivastava M, Shankar G, Tripathi MN, Paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections (PANDAS): A case reportJournal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research 2012 5:1298-300. [Google Scholar]

[12]. Maini B, Bathla M, Dhanjal GS, Sharma PD, Paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders after streptococcus infectionIndian J Psychiatry 2012 54(4):375-77. [Google Scholar]

[13]. Sankaranarayanan A, John JK, Paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders (PANDAS): A case reportNatl Med J India 2003 16(1):22-23. [Google Scholar]

[14]. Mondal A, Ghosh S, Bag S, Paediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorder Associated with Streptococcal Infection (PANDAS): A Case SeriesMedical Journal of Dr DY Patil University 2024 17(1):75-79. [Google Scholar]

[15]. Goodman WK, Scahill L, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, Riddle MA, Rapoport JL, Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (CY-BOCS) 1991 29New Haven, ConnecticutClinical Neuroscience Unit:31-51. [Google Scholar]

[16]. WHOICD-11 [Internet][cited 2024 Jun 15]. Available from: https://icd.who.int/en [Google Scholar]

[17]. RAPID ASO (Latex Slide Test)Available from: https://biolabdiagnostics.com/rapid-aso-latex-slide-test [Google Scholar]

[18]. Haas M, Jakubovski E, Fremer C, Dietrich A, Hoekstra PJ, Jäger B, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale (YGTSS): Psychometric quality of the gold standard for tic assessment based on the large-Scale EMTICS StudyFront Psychiatry [Internet] 2021 Feb 25 [cited 2024 Jun 27] 12:626459Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.626459/full [Google Scholar]

[19]. Tolin DF, Frost RO, Steketee G, A brief interview for assessing compulsive hoarding: The Hoarding Rating Scale-InterviewPsychiatry Res 2010 178(1):147-52. [Google Scholar]

[20]. Murphy TK, Gerardi DM, Parker-Athill EC, The PANDAS controversy: Why (and how) is it still unsettled?Curr Dev Disord Rep 2014 1(4):236-44. [Google Scholar]

[21]. Balasubramanian S, Amperayani S, Dhanalakshmi K, Senthilnathan S, Chandramohan V, Rapid antigen diagnostic testing for the diagnosis of group A beta-haemolytic streptococci pharyngitisNatl Med J India 2018 31(1):08-10. [Google Scholar]

[22]. Moretti G, Pasquini M, Mandarelli G, Tarsitani L, Biondi M, What every psychiatrist should know about PANDAS: A reviewClin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health 2008 4:13 [Google Scholar]

[23]. Mell LK, Davis RL, Owens D, Association between streptococcal infection and obsessive-compulsive disorder, Tourette’s syndrome, and tic disorderPaediatrics 2005 116(1):56-60. [Google Scholar]

[24]. Marconi D, Limpido L, Bersani I, Giordano A, Bersani G, PANDAS: A possible model for adult OCD pathogenesisRiv Psichiatr 2009 44(5):285-98. [Google Scholar]

[25]. Giedd JN, Rapoport JL, Garvey MA, Perlmutter S, Swedo SE, MRI assessment of children with obsessive-compulsive disorder or tics associated with streptococcal infectionAm J Psychiatry 2000 157(2):281-83. [Google Scholar]

[26]. Murphy ML, Pichichero ME, Prospective identification and treatment of children with paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorder associated with group a streptococcal infection (PANDAS)Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002 156(4):356-61. [Google Scholar]

[27]. Orefici G, Cardona F, Cox CJ, Cunningham MW, Paediatric Autoimmune Neuropsychiatric Disorders Associated with Streptococcal Infections (PANDAS). In: Ferretti JJ, Stevens DL, Fischetti VA, editorsStreptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations [Internet] 2016 Oklahoma City (OK)University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center[cited 2024 Mar 25]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK333433/ [Google Scholar]

[28]. Paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatry disorder associated with group a streptococcal infection: The role of surgical treatment [Internet][cited 2024 Mar 27]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/epdf/10.1177/039463201402700307 [Google Scholar]

[29]. Frankovich J, Swedo S, Murphy T, Dale RC, Agalliu D, Williams K, Clinical management of paediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome: Part II-use of immunomodulatory therapiesJ Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2017 27(7):574-93. [Google Scholar]

[30]. Kuluva J, Hirsch S, Coffey B, PANDAS and paroxysms: A case of conversion disorder?J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2008 18(1):109-15. [Google Scholar]

[31]. Bejerot S, Hesselmark E, Wallén H, Mobarrez F, Landén M, Schwieler L, 57. Paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections perceived as conversion disorder. A case study of a young womanBrain, Behavior, and Immunity 2013 32:e16-17. [Google Scholar]