The NMC has revamped the MBBS curriculum after 21 years by introducing Competency-Based Medical Education (CBME) starting from the 2019 academic year. The new CBME curriculum requires intense professional training in the FC for one month for newly admitted first-year medical students in all medical institutions across India [1]. The main aim of the FC is to sensitise new students, who come from diverse backgrounds, to adapt easily to the professional environment, thereby enhancing their learning experience in the medical program. It also supports the goal of CBME, which seeks to develop Indian Medical Graduate (IMG) into clinicians, lifelong learners, good communicators, team leaders, and professionals committed to excellence [2].

To fulfill the objectives of the six modules of the FC, which cover a wide spectrum of domains, students are taught orientation, attitudes, ethics and professionalism, skills, field visits, language and communication skills, as well as sports and extracurricular activities. For each of these modules, specific learning objectives have been designed within a particular timeframe to ensure uniform execution and achieve the desired outcomes. Many of these objectives in the identified modules must be revisited spirally for additional dedicated outcome-based sessions [2]. This can be accomplished by evaluating the usefulness of the FC program during subsequent years of study. Previous studies have assessed the effectiveness of the foundation course program over one month and found it to be beneficial [3-5]. However, there remains a gap in understanding how effectively students can implement the basic knowledge and skills acquired during the FC in the paraclinical and clinical phases of their education.

This study aims to analyse the usefulness of various components of the FC and to evaluate the effectiveness of the competencies achieved in the first year of the FC, as well as how beneficial these competencies have been in the students’ subsequent years of study.

Materials and Methods

A post-test quasi-experimental study was conducted over a three-year period, spanning the academic years 2019-2020 (150 students), 2020-2021 (150 students), and 2021-2022 (150 students) at SRM Medical College Hospital and Research Institute in Kattangulathur, South India. The total number of participants in the study was 450 (N=450). The participants were first-year medical students, aged between 17 and 20 years. The study was approved by the scientific and Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC), receiving ethical clearance under the number 1162/IEC/2019.

Inclusion criteria: MBBS students from the three academic years of 2019-2021 were included in the study.

Exclusion criteria: There were no exclusion criteria, as all students enrolled in the MBBS program must complete the foundational courses in accordance with NMC norms.

The study parameters include various competencies from the six modules of the NMC [2]. These competencies are listed in [Table/Fig-1].

Various competencies included in each module.

| S. No. | Competencies |

|---|

| 1. | Role of doctors in the society |

| 2. | Immunisation requirements of healthcare professionals |

| 3. | Simulation |

| 4. | Proper hand washing and use of personal protective equipment |

| 5. | Handling and safe disposal of biohazardous materials in a simulated environment |

| 6. | Concept of professionalism and ethics among healthcare professionals |

| 7. | Needle stick injuries and assessment |

| 8. | Observation of biomedical waste segregation in accordance with national regulations |

| 9. | Expectation from society as a doctor |

| 10. | Biosafety and universal precautions |

| 11. | Basic communication skill and listening skills |

| 12. | Role of physicians at various levels of healthcare delivery |

| 13. | Consequences of unprofessional and unethical behaviour |

| 14. | Nature of physician’s work- Altruism (case discussion), integrity, responsibility, duty and trust |

| 15. | Introduction to mentor system |

| 16. | Formative and summative assessment |

| 17. | Interpersonal relationships while working in a healthcare team |

| 18. | Discuss the value, honesty, and respect during interactions with peers, seniors, faculty, other healthcare workers and patients |

| 19. | Understanding collaborative learning |

| 20. | Role of Indian Medical Graduate (IMG) |

| 21. | Introduction to principles of family medicine |

| 22. | History of medicine |

| 23. | Cultural diversities and different cultural values |

| 24. | Career options |

| 25. | Documentation |

| 26. | Learning pedagogy and its role in learning skills |

| 27. | Reflective writing |

| 28. | Time management |

| 29. | Different methods of self-directed learning |

| 30. | Alternate system of medicine |

| 31. | Role of yoga and meditation |

| 32. | Disability competencies |

| 33. | Stress management |

| 34. | Introduction to Learning Management System (LMS) |

| 35. | Field visit |

| 36. | Sports activity |

Study Procedure

Among several models that are used to measure the usefulness of a program, the Kirkpatrick model is frequently used in various educational settings [6]. This model includes four levels of program evaluation: reaction, learning, behaviour, and results [7]. The program was evaluated using the Kirkpatrick model for levels 1 and 2. Level 1 of the model specifically focused on what participants liked and disliked about the training program. Level 2 analysed how well the information was retained by the students. Feedback was collected in two stages for all three batches: at the end of the one-month course in the first year and at the end of the academic year. To study the effectiveness of the first level of this evaluation, “Reaction,” the study assessed the extent to which the participants found the training engaging and relevant. A feedback questionnaire was administered immediately at the end of the four-week training program, based on a five-point Likert scale [8,9]. To evaluate the program’s usefulness in their subsequent years of study, a Kirkpatrick Level 2 feedback questionnaire was collected at the end of the following academic year, also based on a five-point Likert scale.

In addition, to assess the students’ perceptions, open-ended questions were provided, and each response was coded based on common comments and analysed. The questions were completely structured by the medical education team and validated by the curriculum committee. Since this is an NMC program, the focus was on the competencies recommended by the NMC without any changes and aligned them with the questions. Reliability statistics show a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.9 in present study, indicating that the questions are sufficiently consistent and reliable.

A 5-point Likert scale was used for assessing feedback on satisfaction during the assessment phase (1=Highly dissatisfied, 2=Dissatisfied, 3=Moderate, 4=Satisfied, 5=Highly satisfied) and for assessing the usefulness of the program at the end of the second year (1=Highly not useful, 2=Not useful, 3=Moderate, 4=Useful, 5=Highly useful).

Statistical Analysis

A spreadsheet was generated to record responses from the feedback form. Descriptive analysis was conducted using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software version 27.0 (College Station, Texas, USA). Mean values and Standard Deviations (SD) were calculated for student responses to the questionnaire in order to evaluate the various competencies taught in the FC during the session and the perceived usefulness of these competencies after the end of the second academic year. For each pairwise comparison, the non parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed, with a p-value of <0.05 considered significant. The measure of internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha.

For the open-ended inquiries, words were identified with codes or labels, and themes were generated by organising these codes or labels into groups of related words or phrases (axial coding). For each open-ended question, a unique master list of all the codes was created, and the percentage (or number) of comments for each code was determined.

Results

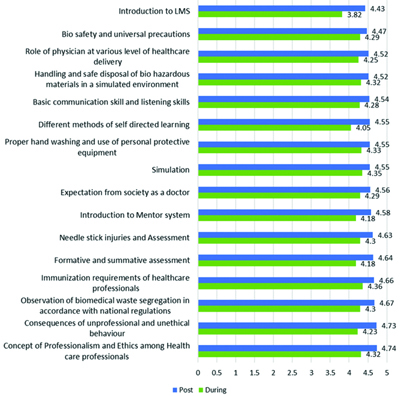

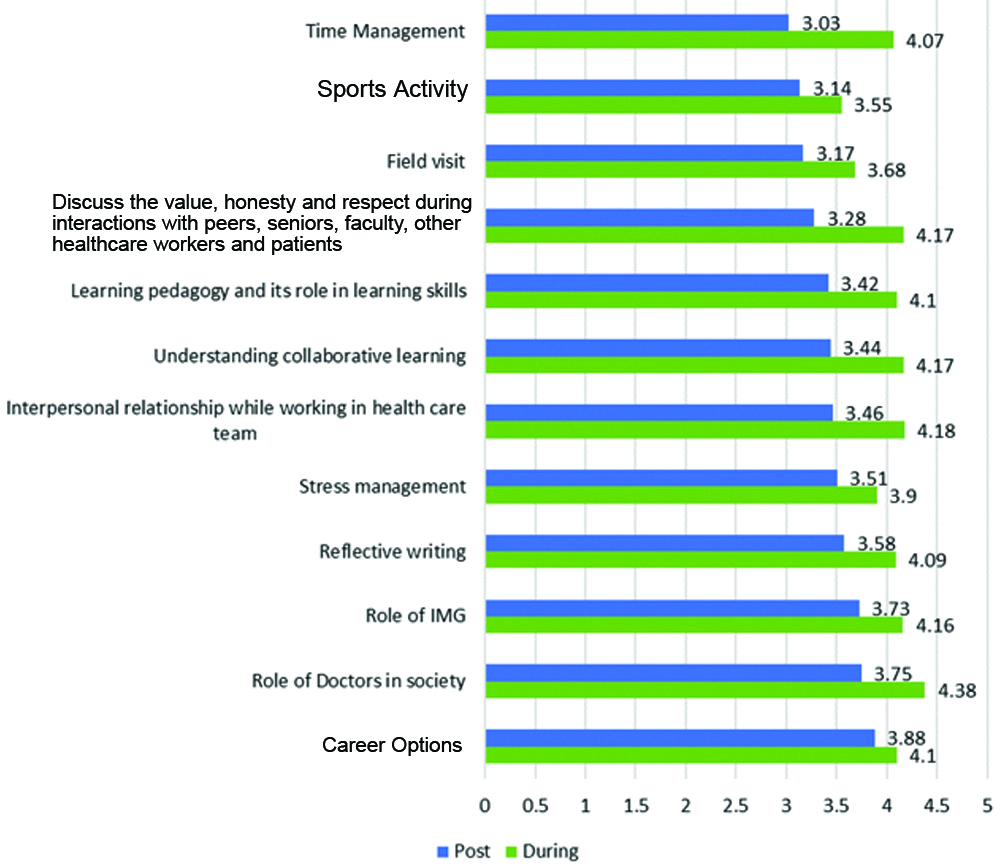

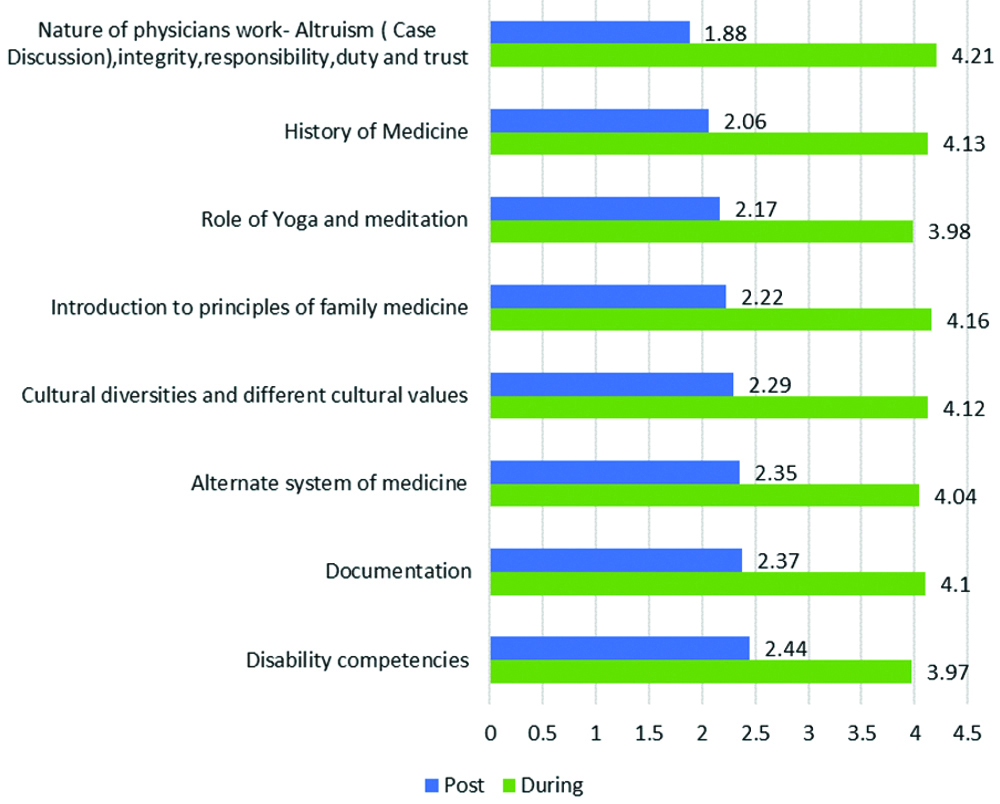

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test for all pair-wise comparisons conducted immediately and at the end of the second year showed a p-value of <0.0001, which indicates statistical significance [Table/Fig-2].

Individual competencies handled in the Foundation Course (FC) immediately after the program and after the end of the next academic year.

| S. No. | Foundation Course (FC) - competencies | Mean±SD immediate | Mean±SD subsequent year | p-value |

|---|

| 1. | Role of doctors in the society | 4.38±0.82 | 3.75±0.59 | <0.001 |

| 2. | Immunisation requirements of healthcare professionals | 4.36±0.81 | 4.66±0.76 | <0.001 |

| 3. | Simulation | 4.35±0.85 | 4.55±0.79 | <0.001 |

| 4. | Proper hand washing and use of personal protective equipment | 4.33±0.83 | 4.55±0.78 | <0.001 |

| 5. | Handling and safe disposal of biohazardous materials in a simulated environment | 4.32±0.83 | 4.52±0.78 | <0.001 |

| 6. | Concept of professionalism and ethics among healthcare professionals | 4.32±0.82 | 4.74±0.79 | <0.001 |

| 7. | Needle stick injuries and assessment | 4.3±0.83 | 4.63±0.73 | <0.001 |

| 8. | Observation of biomedical waste segregation in accordance with national regulations | 4.3±0.83 | 4.67±0.8 | <0.001 |

| 9. | Expectation from society as a doctor | 4.29±0.82 | 4.56±0.84 | <0.001 |

| 10. | Biosafety and universal precautions | 4.29±0.81 | 4.47±0.92 | <0.001 |

| 11. | Basic communication skill and listening skills | 4.28±0.81 | 4.54±0.84 | <0.001 |

| 12. | Role of physicians at various levels of healthcare delivery | 4.25±0.85 | 4.52±0.99 | <0.001 |

| 13. | Consequences of unprofessional and unethical behaviour | 4.23±0.9 | 4.73±0.82 | <0.001 |

| 14. | Nature of physician’s work- Altruism (case discussion), integrity, responsibility, duty and trust | 4.21±0.88 | 1.88±0.96 | <0.001 |

| 15. | Introduction to mentor system | 4.18±0.94 | 4.58±0.75 | <0.001 |

| 16. | Formative and summative assessment | 4.18±0.84 | 4.64±0.81 | <0.001 |

| 17. | Interpersonal relationships while working in a healthcare team | 4.18±0.87 | 3.46±0.84 | <0.001 |

| 18. | Discuss the value, honesty, and respect during interactions with peers, seniors, faculty, other healthcare workers and patients | 4.17±0.87 | 3.28±0.82 | <0.001 |

| 19. | Understanding collaborative learning | 4.17±0.89 | 3.44±1.39 | <0.001 |

| 20. | Role of IMG | 4.16±0.9 | 3.73±0.89 | <0.001 |

| 21. | Introduction to principles of family medicine | 4.16±0.88 | 2.22±1.08 | <0.001 |

| 22. | History of medicine | 4.13±0.92 | 2.06±0.95 | <0.001 |

| 23. | Cultural diversities and different cultural values | 4.12±0.96 | 2.29±1.11 | <0.001 |

| 24. | Career options | 4.1±0.92 | 3.88±0.78 | <0.001 |

| 25. | Documentation | 4.1±0.94 | 2.37±1.13 | <0.001 |

| 26. | Learning pedagogy and its role in learning skills | 4.1±0.91 | 3.42±0.86 | <0.001 |

| 27. | Reflective writing | 4.09±0.93 | 3.58±0.86 | <0.001 |

| 28. | Time management | 4.07±0.95 | 3.03±1.09 | <0.001 |

| 29. | Different methods of self-directed learning | 4.05±0.96 | 4.55±0.82 | <0.001 |

| 30. | Alternate system of medicine | 4.04±0.97 | 2.35±1.09 | <0.001 |

| 31. | Role of yoga and meditation | 3.98±1.04 | 2.17±0.98 | <0.001 |

| 32. | Disability competencies | 3.97±1.1 | 2.44±0.96 | <0.001 |

| 33. | Stress management | 3.9±1.07 | 3.51±0.89 | <0.001 |

| 34. | Introduction to LMS | 3.82±1.14 | 4.43±0.91 | <0.001 |

| 35. | Field visit | 3.68±1.32 | 3.17±1.19 | <0.001 |

| 36. | Sports activity | 3.55±1.37 | 3.14±1.25 | <0.001 |

Data represented as Mean±SD

[Table/Fig-3] presents competencies with a mean score above 4.6/5, demonstrating that these competencies were highly beneficial in the subsequent years. Competencies with a mean score of 3.5/5, as shown in [Table/Fig-4], indicate that these competencies were moderately utilised by the students in the following years, (p-value <0.0001). Similarly, a few competencies received an average score of 2.2/5, indicating that they were the least utilised by the students in the subsequent year of study (p-value <0.0001) [Table/Fig-5].

Foundation Course (FC) most used competencies in subsequent years.

During: Feedback analysis taken at the end of one month

Post: Feedback analysis at the end of academic year

Foundation Course (FC) moderately used competencies in subsequent years.

During: Feedback analysis taken at the end of one month

Post: Feedback analysis at the end of academic year

Foundation Course (FC) least used competencies in subsequent years.

During: Feedback analysis taken at the end of one month

Post: Feedback analysis at the end of academic year

Out of 36 competencies, 16 were identified as most utilised by the students in the following year, 12 were moderately utilised, and eight were least utilised.

Qualitative analysis of student feedback: The analysis of the open-ended questions, after coding common terms, shows that 437 students (97%) reported that the FC was useful, while 13 students (3%) found it to be very useful.

Discussion

The findings of present study indicated that the FC program in a medical school has distinct, yet somewhat overlapping impacts on various competencies taught during the course period, as well as their usefulness in subsequent years of study. Dixit R et al., reported that the overall components of the FC program were statistically significant and well received by the students [3]. Mishra P and Kar M; Mittal R et al., investigated the effectiveness of the FC program for MBBS students, discussing its usefulness to the student community and concluded that it was empowering for starting a medical career and should be included in the curriculum [10,11]. Vyas S et al., observed that students had the most positive perceptions regarding skill development, community orientation, and field visits [12], while communication and language skills were perceived less favourably. In contrast, Pandey AK et al., demonstrated similar results, with the skill module being rated as excellent by the students, whereas community orientation received a lower rating [13].

The study described here showed an increase in the average scores for skill competencies and orientation modules. In another study by James T et al., sessions on skill modules, including Basic Life Support (BLS) and first aid, received excellent scores, while orientation modules and language enhancement received the lowest ratings [14]. Our findings are consistent with the aforementioned study regarding skill competencies and language sessions, but not for the orientation module. This suggests that students were more interested in learning psychosomatic skills rather than the cognitive domain involving lectures. Velusami D et al., reported that sessions on mentoring, self-directed learning, orientation to health systems, professional development, ethics, and communication skills were highly appreciated by participants, while competencies such as interpersonal skills, documentation, stress management, LMS, and the role of yoga and sports activities were identified as areas needing further improvement [15]. The present study aligns closely with the findings of the above study regarding these challenging competencies. Concerning the competencies covered in the computer module, overall, the students felt that they were basic and that they had prior knowledge about them.

The major disadvantage of a few competencies was that the sessions were conducted as lectures, resulting in a lack of opportunity for students to interact and process the information presented [16,17]. On the other hand, faculty members need to be trained to support the implementation of the NMC curriculum, and the high student-to-faculty ratio must be addressed, as these are considered major challenges to the effective implementation of the new curriculum [18-20].

This pattern suggests that efforts could be made to redesign a few modules, such as those related to computers, community orientation, sports, and extracurricular activities. A study by Raveendra L et al., identified similar challenges in these modules and recommended proper planning and coordination among faculty, as well as the optimal use of available infrastructure resources to overcome these issues [21]. Misra S et al., in their study, noted the challenges faced in the FC and suggested reducing the duration of the FC to avoid redundancy [22].

One of the most compelling aspects of assessing the FC program is evaluating the effectiveness of the competencies learned in subsequent years. However, the usefulness of the FC competencies over time was not reported in any studies. Since the FC is a mandatory program for all undergraduate MBBS students as per NMC regulations, this program needs to be analysed for optimisation, correction, and future recommendations to align with the goal of producing Indian medical graduate who meet global competencies. Overall, the majority of competencies were scored good and retained well by students, but a few-including those related to computers, sports, and extracurricular activities-may benefit from outsourcing faculty from other disciplines for better updates and execution processes.

While analysing the effectiveness of usage over the study period using Kirkpatrick’s Level 2, a few competencies had a mean score above 4.5/5, reflecting high effectiveness in subsequent years. There are conflicting reports from several sessions regarding the effectiveness of the learned competencies in the following year of study. Present study found that competencies such as the history of medicine, the role of yoga and meditation, an introduction to family medicine, altruism, documentation, alternative systems of medicine, and disability competencies were highly appreciated by the students immediately after the session, with a mean score of 4 to 4.5 out of 5. However, contradicting results were observed regarding their effectiveness in subsequent academic years, with a mean score of 1 to 2.5 out of 5. This indicates that although these sessions received positive feedback immediately after the program, their practical application in the students’ ongoing studies was limited. This suggests a need for future improvement and modification.

Limitation(s)

This study was conducted at a single private medical college in South India; therefore, the findings cannot be generalised. It is highly recommended to extend this study to a larger geographical area.

Conclusion(s)

The NMC-mandated FC program evaluation, both in terms of overall immediate performance and its effectiveness in subsequent years, was very satisfactory. Additionally, this study observed mixed responses regarding the effectiveness of individual competencies in the following academic years. Therefore, this study recommends modifications to the module, the methodology, or the duration of teaching hours for those competencies to achieve the desired outcomes.

Data represented as Mean±SD