Introduction

Cardiac remodeling is a physiological and pathological condition followed by Myocardial Infarction (MI), valvular dysfunctions and cardiomyopathy. It is associated with cardiac function and structural characteristics. Hence, the remodeling is a therapeutic target following cardiac events.

Aim

This review was conducted to determine the risk of morbidity, mortality and structural characteristics related cardiac remodeling.

Materials and Methods

PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and ProQuest, were searched electronically, by using {(“Morbidity” and “Mortality” and “LV parameters” and “Structural Characteristics”) and Cardiac (“Remodeling” and “Regeneration”)}. “Mantel-Haenszel Odds Ratio”, “mean differences”, and “95% Confidence Interval (CI)” were computed for meta-analysis.

Results

Overall, 425 titles or abstracts were identified from the initial search, of which full manuscripts of 103 studies were retrieved. Out of the 103 studies, 22 were subjected to data extraction and analysis. The risk of mortality was higher among patients with myocardial fibrosis. Metoprolol treated group had a lesser incidence of Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation (PAF). Ejection fraction, end systolic and diastolic volumes were consistent between the medical treatments and Percutaneous Coronary Interventions (PCI) groups.

Conclusion

The PCIs are associated with long term survival among the patients with cardiac remodeling.

Introduction

The ability of the heart to regenerate following ischaemia is quite restricted. Cardiac remodelling consists of thickening (hypertrophy) and stiffening (fibrosis) of the left ventricular wall [1]. It is a physiological and pathological condition that may occur with the progression of ischaemia or reperfusion, cardiac failure, cardiac tumour, myocardial infarction, cardiac cancers, eugenics, aortic stenosis, hypertension, myocarditis, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy or valvular regurgitation [1-4].

The remodelling is characterised by endothelin, cytokines, nitric oxide production and oxidative stress [5]. After cardiac injury, there occurs deposition of non contractile scar tissue, which results in cardiac remodelling and a resultant impaired cardiac function. The fibrotic response is mediated by fibroblasts and myofibroblasts. The scar formation helps to prevent rupture of ventricular wall after an ischaemic insult [6-9].

Increased stiffness of myocardium and diminished contractility are the consequences of pathological remodelling [10-12]. Major changes that occur after an insult are cardiomyocyte lengthening and ventricular wall thinning [3]. Despite treatment advancements, cardiac remodelling and dysfunction-related mortality rates remain high [12]. As a result, it is critical to comprehend the pathophysiological mechanisms involved in the remodelling process. Hence, determining the mortality, morbidity, and structural properties of the myocardium in relation to cardiac remodelling would be intriguing. This review was conducted to determine the risk of morbidity, mortality and structural characteristics related cardiac remodelling.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review was conducted from October 2020 to March 2021 including the English literature from January 1990 to December 2020 at Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Imperial College, London, United Kingdom.

Inclusion criteria: Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs), quasi experimental and descriptive studies, which made an attempt to address the effects of cardiac remodelling, were included. The manuscript published (English literature) from January 1990 to December 2020 were included. The studies conducted on adult patients who underwent cardiac remodelling irrespective of study setting and regions were included.

Exclusion criteria: Studies conducted among paediatrics, case reports, and case series were excluded.

PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and ProQuest, were searched electronically, by using {(“Morbidity” or “Mortality” or “LV parameters” or “Structural Characteristics”) and Cardiac (“Remodelling” or “Regeneration”)}. The Cochrane Central Register of controlled trials was also searched to get the studies.

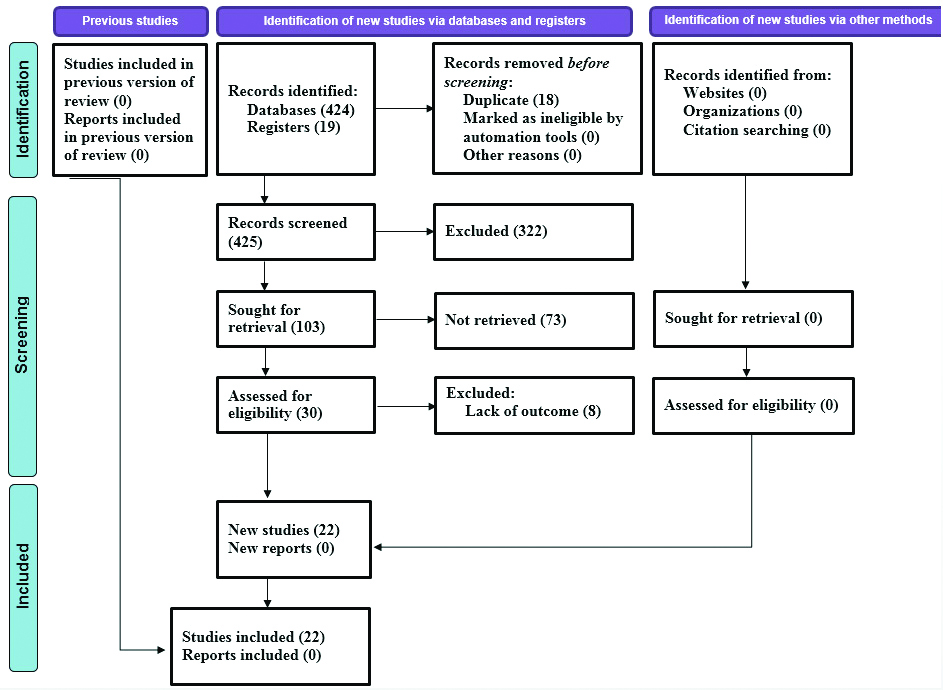

Search strategy: Criteria for screening all the identified articles were primarily based on, “Whether the studies addressed any kind of outcomes on the effects of cardiac remodelling on morbidity, mortality and structural properties of the myocardium in relation to cardiac remodelling [Table/Fig-1]?”

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

Quality Assessment

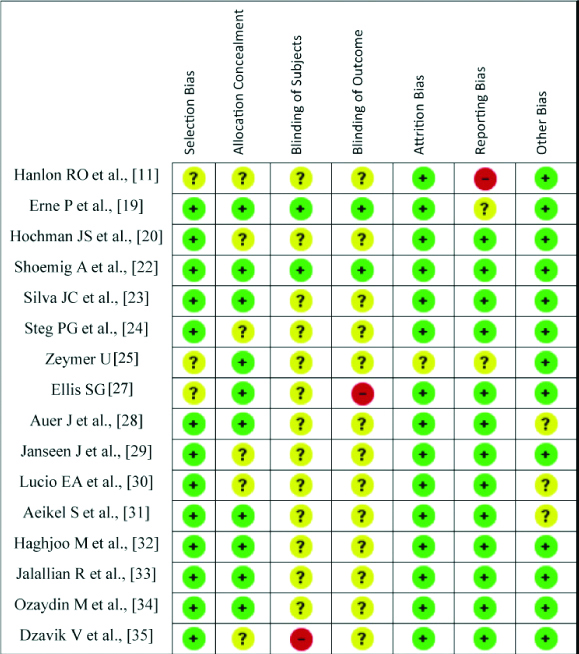

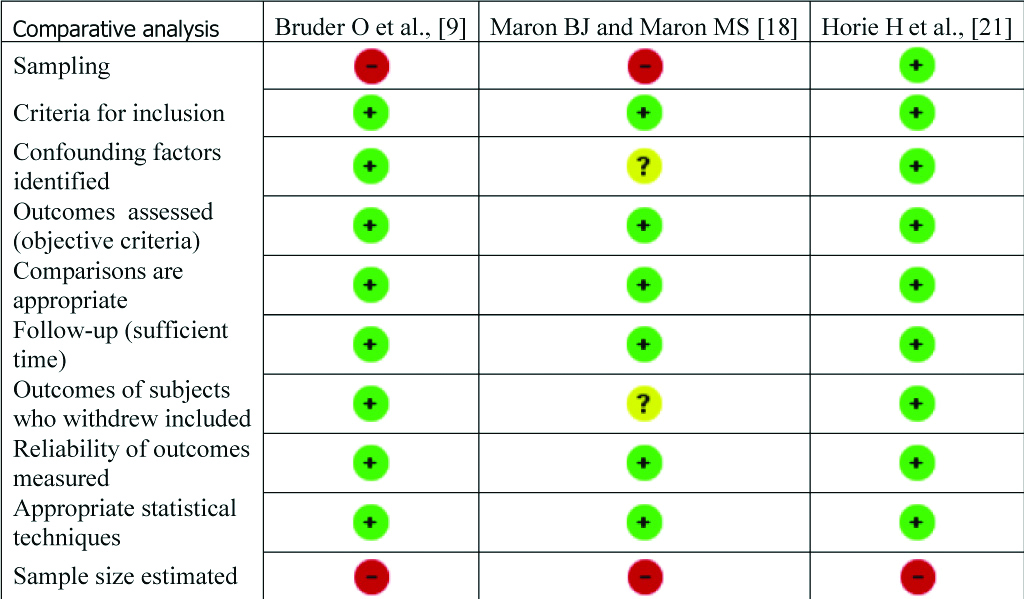

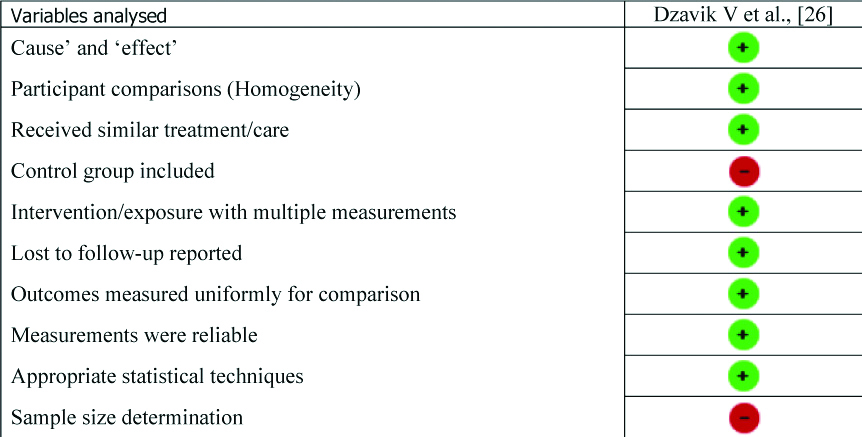

All the included studies [Table/Fig-2] [9-11,17-35] were subjected to critical appraisal using the “Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool” and “Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklist for descriptive and quasi experimental studies” [13,14]. Each criterion was appraised as “Low Risk of Bias” (+), “Unclear Risk of Bias” (?) and “High Risk of Bias” (-) [Table/Fig-3,4 and 5].

| Study | Study design | Sample size | Outcomes on cardiac remodeling |

|---|

| Bruder O et al., [9] | Descriptive | 220 | Mortality |

| Chan RH et al., [10] | Cohort | 1293 | Mortality |

| O’Hanlon RO et al., [11] | RCT | 217 | Mortality |

| Ismail TF et al., [17] | Cohort | 711 | Mortality |

| Maron BJ and Maron MS [18] | Descriptive | 222 | Mortality |

| Erne P et al., [19] | RCT | 201 | Mortality, ejection fraction |

| Hochman JS et al., [20] | RCT | 66 | Mortality |

| Horie H et al., [21] | Descriptive | 83 | Mortality |

| Shoemig A et al., [22] | RCT | 365 | Mortality |

| Silva JC et al., [23] | RCT | 36 | Mortality |

| Steg PG et al., [24] | RCT | 212 | Mortality, ejection fraction |

| Zeymer U et al., [25] | RCT | 300 | Mortality |

| Dzavik V et al., [26] | Quasi experimental | 44 | Mortality |

| Ellis SG et al., [27] | RCT | 87 | Mortality |

| Auer J et al., [28] | RCT | 127 | Postoperative atrial fibrillation |

| Janseen J et al., [29] | RCT | 89 | Postoperative atrial fibrillation |

| Lucio EA et al., [30] | RCT | 200 | Postoperative atrial fibrillation |

| Aeikel S et al., [31] | RCT | 110 | Postoperative atrial fibrillation |

| Haghjoo M et al., [32] | RCT | 120 | Postoperative atrial fibrillation |

| Jalallian R et al., [33] | RCT | 150 | Postoperative atrial fibrillation |

| Ozaydin M et al., [34] | RCT | 207 | Postoperative atrial fibrillation |

| Dzavik V et al., [35] | RCT | 353 | Structural characteristics |

RCT: Randomised controlled trial

Critical appraisal (RCT).

Critical appraisal (Descriptive).

Critical appraisal (Quasi Experimental).

Statistical analysis

For meta-analysis, “Mantel–Haenszel Odds Ratio”, “mean differences”, and “95% Confidence Interval (CI)” were computed. The “Chi-square statistic with p-value <0.10 and I2 statistic >65% were used to test heterogeneity” of the included studies [15]. The “Review Manager Software (Rev Man 5, Cochrane collaboration, Oxford, England)” was used for data analytics [16].

Results

Overall, 425 citations were identified, of which 103 studies were retrieved. Later, 73 studies were excluded. Of the remaining 30 studies, 22 were subjected to meta-analysis [Table/Fig-1] [9-11,17-35].

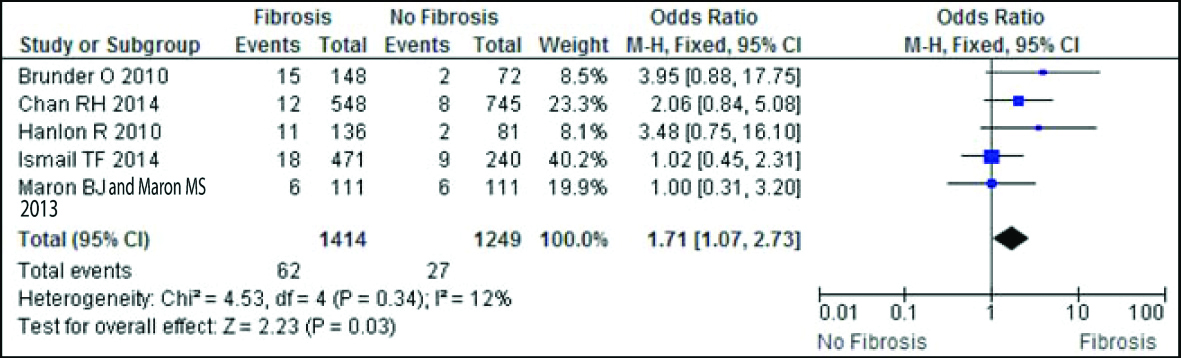

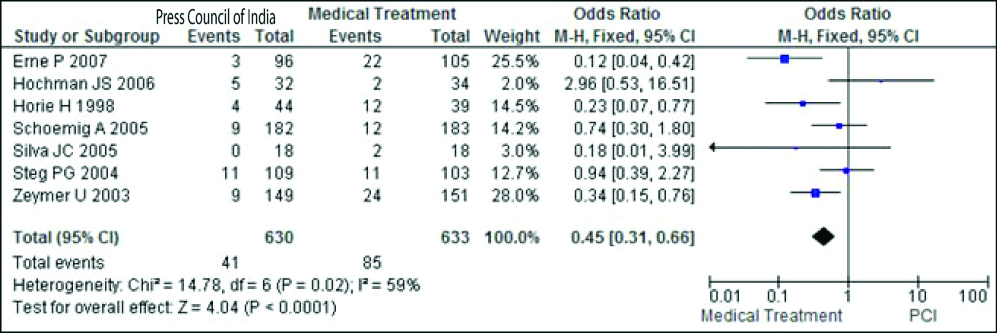

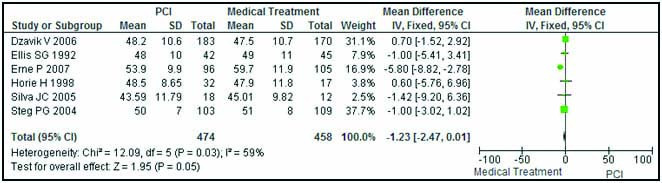

The risk of mortality was compared between patients without myocardial fibrosis and who demonstrated myocardial fibrosis. It was higher among patients with myocardial fibrosis and it favours in adults with PCI, when compared with medical treatment group [Table/Fig-6,7].

Risk of mortality according to myocardial fibrosis.

Risk of mortality according to PCI and medical treatment.

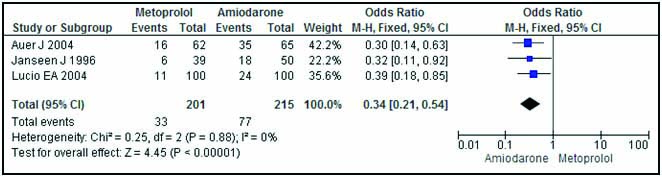

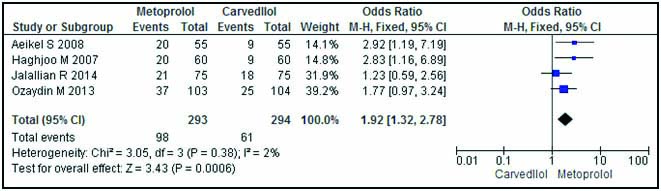

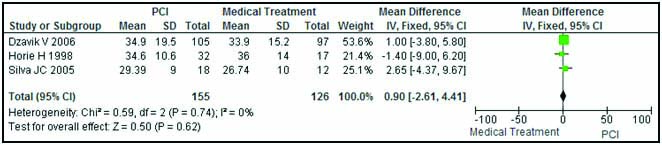

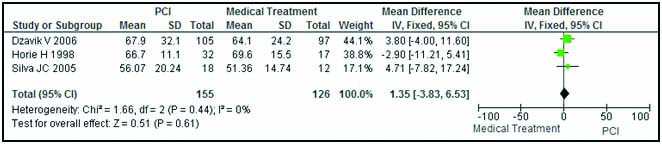

The PAF was lesser among the people treated with Metoprolol compared to Amiodarone group. The Carvedilol received group favours PAF compared to Metoprolol group [Table/Fig-8,9]. Structural characteristics such as: ejection fraction (%), end systolic volume Index, and end diastolic volume index were homogeneous according to the groups PCI and medical treatments [Table/Fig-10,11 and 12].

Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation (PAF) according to Metoprolol and Amiodarone.

Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation (PAF) according to Metoprolol and Carvedilol.

Ejection fraction (%) according to Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI) and medical treatment.

End systolic volume according to PCI and medical treatment.

End diastolic volume according to PCI and medical treatment.

Discussion

This study suggested that myocardial fibrosis is associated with cardiac mortality. Among asymptomatic cardiomyopathy patients; the presence of scar indicated by cardiac magnetic resonance is an independent predictor of cardiac mortality.

Metoprolol significantly, reduced PAF compared to Amiodarone. In the Metoprolol versus Carvedilol comparison, Metoprolol increased the risk of PAF compared with Carvedilol. Carvedilol is better than Metoprolol in reducing PAF among cardiac cases. The development of PAF is associated with increased risk of thrombotic events, such as: stroke, phlebitis, MI and prolonged hospital stay [8].

Cardiac remodelling is accompanied by myocyte growth, fibrosis, electrophysiological changes, and inflammation. These events are interdependent and can target the molecular and cellular mechanisms of the remodelling [36]. The myocardial damage, cell death zone within the ventricle, and loss of contractility in the affected area enhance the magnitude of remodelling. These changes, along with morphological alterations can be detected through echocardiography (ECG), ventriculography, and nuclear magnetic resonance [37].

This study suggests that myocardial fibrosis is associated with cardiac mortality. Among asymptomatic cardiomyopathy patients; the presence of scar indicated by cardiac magnetic resonance is an independent predictor of cardiac mortality, ventricular fibrillation, and tachycardia [38].

In this study, a lower mortality rate was observed after percutaneous coronary interventions. The use of drug-eluting stents or implantation techniques, arterial bypass grafting, may improve the prognosis followed by cardiac remodelling. Stent related repeat revascularisation may provide better benefits for patient survival. The left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy cases are at higher risk for malignant arrhythmias, accounting for a substantial increase in the mortality associated with cardiac hypertrophy. Ventricular tachyarrhythmia is a major determinant of mortality in patients with left ventricular heart failure [39].

The development of postoperative atrial fibrillation (POAF) is associated with increased risk of thrombotic events, such as: stroke, phlebitis, myocardial infarction and prolonged hospital stay [8]. Use of Metoprolol, reduced POAF compared to Amiodarone. The beta blocker Metoprolol controlled release/extended release (CR/XL) is effective in strengthening sinus rhythm after atrial fibrillation and hence it is the first line treatment regimen among atrial fibrillation cases [40]. In this study, Metoprolol increased the risk of POAF compared with Carvedilol. Use of Carvedilol is better than Metoprolol in reducing POAF and it is recommended for the cardiac cases with NYHA class II or III. Treatment with Carvedilol improved LV function and reduced the risk of mortality [41].

Although the ejection fraction (EF), end systolic/diastolic volumes are associated with PCI and medical treatments, in this study, there was no difference in the EF and volumes between PCI and medical treatments. Decreased EF is a potential determinant of cardiovascular outcomes followed by PCI and the mortality rates of patients with low EF was higher than cases with normal EF [23]. The left ventricular volumes along with EF have prognostic efficacy in the remodelling process and they are considered to be surrogate endpoints for cardiac remodelling [42].

Despite improvement in remodelling techniques, among the patients with a low EF, the coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is superior to medical therapy alone, in terms of clinical improvement and long-term survival. The Systolic LV function is a known predictor of in-hospital mortality after CABG [43]. The patients with low EF is more likely to isolate for CABG provided the indication is angina, instead heart failure. However, the reduced preoperative EF may result in the higher incidences of postoperative mortality. Hence, the observations about the LV function, ischaemia, and coronaries are important to decide the treatment regimen among cardiac cases.

The requirement for relapsed revascularisation followed by the remodelling is an adverse outcome and it enhances the likelihood of re hospitalisation. Among PCI cases, the need for revascularisation is associated with stent-related complications [43].

Limitation(s)

In this review, there was no comparison of follow-up data (at least thirty days) of the determinants of cardiac remodelling. Data on infarct size, anterior location, and the perfusion status of the Infarct Related Artery (IRA) haven’t been studied in this review.

Conclusion(s)

Percutaneous Coronary Interventions are associated with long term survival among the patients with cardiac remodelling. The postoperative atrial fibrillation can be prevented by using Metoprolol.

[1]. Talman V, Ruskoaho H, Cardiac fibrosis in myocardial infarction- from repair and remodeling to regenerationCell Tissue Res 2016 365(3):563-81.10.1007/s00441-016-2431-927324127 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Schirone L, Forte M, Palmerio S, Yee D, Nocella C, Angelini F, A review of the molecular mechanisms underlying the development and progression of cardiac remodelingOxid Med Cell Longev 2017 2017:392019510.1155/2017/392019528751931 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[3]. Cohn JN, Roberto F, Norman S, Cardiac remodeling- concepts and clinical implications: A consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodelingJ Am Coll Cardiol 2000 35(3):569-82.10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00630-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[4]. Zhang Y, Mignone J, MacLellan Cardiac regeneration and stem cellsPhysiol Rev 2015 95(4):1189-204.10.1152/physrev.00021.201426269526 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[5]. Mihl C, Dassen WR, Kuipers H, Cardiac remodelling: Concentric versus eccentric hypertrophy in strength and endurance athletesNeth Heart J 2008 16(4):129-33.10.1007/BF0308613118427637 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Yang D, Liu HQ, Liu FY, Tang N, Guo Z, Ma SQ, The roles of noncardiomyocytes in cardiac remodelingInt J Biol Sci 2020 16(13):2414-29.10.7150/ijbs.4718032760209 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Hashimoto H, Olson EN, Duby RB, Therapeutic approaches for cardiac regeneration and repairNat Rev Cardiol 2018 15(10):585-600.10.1038/s41569-018-0036-629872165 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Zgheib C, Hodges MM, Allukian MW, Gorman JH, Gorman RC, Liechty KW, Cardiac progenitor cell recruitment drives fetal cardiac regeneration by enhanced angiogenesisAnn Thorac Surg 2017 104(6):1968-76.10.1016/j.athoracsur.2017.05.04028821329 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[9]. Bruder O, Wagner A, Jensen CJ, Schneider S, Ong P, Kispert EM, Myocardial scar visualized by cardiovascularmagnetic resonance imaging predicts major adverse events in patients withhypertrophiccardiomyopathyJ Am Coll Cardiol 2010 56(11):875-87.10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.00720667520 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Chan RH, Maron BJ, Olivotto I, Pencina MJ, Assenza GE, Haas T, Prognostic value of quantitativecontrast-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the evaluation of suddendeath risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathyCirculation 2014 130(6):484-95.10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.00709425092278 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. O’Hanlon RO, Grasso A, Roughton M, Moon JC, Clark S, Wage R, Prognostic significance of myocardialfibrosis in hypertrophic cardiomyopathyJ Am Coll Cardiol 2010 56(11):867-74.10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.01020688032 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[12]. Azevedo PS, Polegato BF, Minicucci MF, Paiva SA, Zornof LA, Cardiac remodeling: concepts, clinical impact, pathophysiological mechanisms and pharmacologic treatmentArq Bras Cardiol 2016 106(1):62-69.10.5935/abc.20160005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[13]. Higgins JP, Green S, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.1.0The Cochrane Collaboration 2011 Available from: www.handbook.cochrane.org [Google Scholar]

[14]. The Joanna Briggs InstituteJoanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual 2011 The University of Adelaide South Australia 500510.1136/bmj.327.7414.55712958120 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[15]. Julian PT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG, Measuring inconsistency in Meta analysisBMJ 2003 327:557-60.10.1136/bmj.327.7414.55712958120 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[16]. RevMan 5 download RevMan web page. www.cc-ims.net/RevMan [Google Scholar]

[17]. Ismail TF, Jabbour A, Gulati A, Mallorie A, Raza S, Cowling TE, Role of late gadolinium enhancementcardiovascular magnetic resonance in the risk stratification of hypertrophiccardiomyopathyHeart 2014 100(23):1851-58.10.1136/heartjnl-2013-30547124966307 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[18]. Maron BJ, Maron MS, Hypertrophic cardiomyopathyLancet 2013 381(9862):242-55.10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60397-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[19]. Erne P, Schoenenberger AW, Burckhardt D, Zuber M, Kiowski W, Buser PT, Effects of percutaneous coronary interventions in silent ischemia after myocardialinfarction. The SWISSI II randomised controlled trialJAMA 2007 297(18):1985-91.10.1001/jama.297.18.198517488963 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[20]. Hochman JS, Lamas GA, Buller CE, Dzavik V, Reynolds HR, Abramsky SJ, Coronary intervention forpersistent occlusion after myocardial infarctionN Engl J Med 2006 355(21):2395-407.10.1056/NEJMoa06613917105759 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[21]. Horie H, Takahashi M, Minai K, Izumi M, Takaoka A, Nozawa M, Long-term beneficial effect oflate reperfusion for acute anterior myocardial infarction with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplastyCirculation 1998 98(22):2377-82.10.1161/01.CIR.98.22.23779832481 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[22]. Schoemig A, Mehilli J, Antoniucci D, Ndrepepa G, Markwardt C, Pede FD, Mechanical reperfusion inpatients with acute myocardial infarction presenting more than twelve hours from symptom onsetJAMA 2005 293(23):2865-72.10.1001/jama.293.23.286515956631 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[23]. Silva JC, Rochitte CE, Junior JS, Tsutsui J, Andrade J, Martinez EE, Late coronary artery recanalization effects on left ventricular remodeling and contractility bymagnetic resonance imagingEur Heart J 2005 26(1):36-43.10.1093/eurheartj/ehi01115615797 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[24]. Steg PG, Thuaire C, Himbert D, Carrie D, Champagne S, Coisne D, DECOPI (DEsobstructionCOronaireen Post-Infarctus): A randomised multi-centre trial of occluded artery angioplasty after acute myocardial infarctionEur Heart J 2004 25(24):2187-94.10.1016/j.ehj.2004.10.01915589635 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[25]. Zeymer U, Uebis R, Vogt A, Glunz HG, Vohringer HF, Harmjanz D, Randomised comparison of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty and medical therapy instable survivors of acute myocardial infarction with single vessel diseaseCirculation 2003 108(11):1324-28.10.1161/01.CIR.0000087605.09362.0E12939210 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[26]. Dzavik V, Beanlands DS, Davies RF, Leddy D, Marquis JF, Teo KK, Effects of late percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty of an occluded infarct-related coronary artery on left ventricular function in patients with a recent (6weeks) Q-wave acute myocardial infarction (Total occlusion post myocardial infarction interventional study [TOMIIS]–a pilot study)Am J Cardiol 1994 73:856-61.10.1016/0002-9149(94)90809-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[27]. Ellis SG, Mooney MR, George BS, Ribeiro da Silva EE, Talley JD, Flanagan WH, Randomised trial of late elective angioplasty versus conservative management for patients withresidual stenosis after thrombolytic treatment of myocardial infarction. Treatment of post-thrombolytic stenosis (TOPS) study groupCirculation 1992 86(5):1400-06.10.1161/01.CIR.86.5.14001423952 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[28]. Auer J, Weber T, Berent R, Puschmann R, Hartl P, Ng CK, A comparison between oralantiarrhythmic drugs in the prevention of atrial fibrillation aftercardiac surgery: The pilot study of prevention of postoperative atrialfibrillation (SPPAF), a randomised, placebo-controlled trialAm Heart J 2004 147:636-43.10.1016/j.ahj.2003.10.04115077078 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[29]. Janssen J, Loomans L, Harink J, Taams M, Brunninkhuis L, Starre P, Prevention and treatment of supraventricular tachycardia shortly after coronary artery bypassgrafting: A randomised open trialAngiology 1986 37(8):601-09.10.1177/0003319786037008072874755 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[30]. Lúcio EA, Flores A, Blacher C, Leães PE, Lucchese FA, Ribeiro JP, Effectiveness of metoprolol in preventing atrial fibrillation in the postoperative period of coronary artery bypass graft surgeryArq Bras Cardiol 2004 82(1):42-46.10.1590/S0066-782X2004000100004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[31]. Aeikel S, Bozbas H, Gultekin B, Aydinalp A, Saritas B, Bal U, Comparison of the efficacy of Metopolol and Carvedilol for preventing atrial fibrillation aftercoronary bypass surgeryInt J Cardiol 2008 126(1):108-13.10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.03.12317499863 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[32]. Haghjoo M, Saravi M, Hashemi MJ, Fazelifar AF, Alizadeh A, Sadr-Ameli MA, Optimal beta-blockerfor prevention of atrial fibrillation after on-pump coronary artery bypass graft surgery: Carvedilol versus MetopololHeart Rhythm 2007 4(9):1170-74.10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.04.02217765616 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[33]. Jalalian R, Ghafari R, Ghazanfari P, Comparing the therapeutic effects of Carvedilol and metoprolol on prevention of atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery, a double-blind studyInt Cardiovasc Res J 2014 8(3):111-15. [Google Scholar]

[34]. Ozaydin M, Icli A, Yucel H, Akcay S, Peker O, Erdogan D, Metopolol vs. Carvedilol or Carvedilol plus N-acetyl cysteine on post-operative atrial fibrillation: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyEur Heart J 2013 34(8):597-604.10.1093/eurheartj/ehs42323232844 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[35]. Dzavik V, Buller CE, Lamas GA, Rankin JM, John MB, Cantor WJ, TOSCA-2 InvestigatorsRandomised trial of percutaneous coronary intervention for sub acute infarct-related coronary artery occlusion to achieve long-term patency and improve ventricular function. The Total Occlusion Study of Canada (TOSCA)-2 trialCirculation 2006 114(23):2449-57.10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.66943217105848 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[36]. Xie M, Burchfield JS, Hill JA, Pathological ventricular remodeling: Mechanisms: Part 1 of 2Circulation 2013 128(4):388-400.10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.00187823877061 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[37]. Zornoff LA, Paiva SA, Duarte DR, Spadaro J, Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction: Concepts and clinical implicationsArq Bras Cardiol 2009 92(2):157-64.10.1590/S0066-782X2009000200013 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[38]. Gulati A, Jabbour A, Ismail TF, Guha K, Khwaja J, Raza S, Association of fibrosis with mortality and sudden cardiac death in patients with non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathyJAMA 2013 309(9):896-908.10.1001/jama.2013.136323462786 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[39]. Topkara VK, Cheema FH, Kesavaramanujam S, Mercando ML, Cheema AF, Namerow PB, Coronary artery bypass grafting in patients with low ejection fractionCirculation 2005 112(1):344-50.10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.52627716159844 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[40]. Kuhilkamp V, Bosch R, Mewis C, Seipel L, Use of beta-blockers in atrial fibrillationAm J Cardiovasc Drugs 2002 2(1):37-42.10.2165/00129784-200202010-0000514727997 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[41]. Giustino G, Serruys PW, Sabik JF, Mehran R, Maehara A, Puskas JD, Mortality after repeat revascularization following PCI or CABG for left main disease: The EXCEL TrialJ Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2020 13:375-87.10.1016/j.jcin.2019.09.01931954680 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[42]. Kato M, Kitada S, Kawada Y, Nakasuka K, Kikuchi S, Seo Y, Left ventricular end-systolic volume is a reliable predictor of new-onset heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fractionCardiol Res Pract 2020 2020:310601210.1155/2020/310601232670635 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[43]. Head SJ, Milojevic M, Daemen J, Ahn JM, Boersma E, Christiansen EH, Mortality after coronary artery bypass grafting versus percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting for coronary artery disease: A pooled analysis of individual patient dataLancet 2018 391:939-48.10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30423-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]