Chlorpromazine and Trifluperazine Induced Parkinsonism in a Patient with Insomnia

S Girija1, N Naresh Kumar2, N Natis Prasannaa3, S Sarumathy4, R Nanda Kumar5

1 Department of Pharmacy Practice, SRM College of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, SRMIST, Kattankulathur, Tamil Nadu, India.

2 Department of Pharmacy Practice, SRM College of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, SRMIST, Kattankulathur, Tamil Nadu, India.

3 Department of Pharmacy Practice, SRM College of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, SRMIST, Kattankulathur, Tamil Nadu, India.

4 Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice, SRM College of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, SRMIST, Kattankulathur, Tamil Nadu, India.

5 Associate Professor, Department of General Medicine, SRM Medical College Hospital and Research Centre, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, SRMIST, Kattankulathur, Tamil Nadu, India.

NAME, ADDRESS, E-MAIL ID OF THE CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: S Sarumathy, Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice, SRM College of Pharmacy, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Kattankulathur, Chengalpattu (DT)-603203, Tamil Nadu, India.

E-mail: saruprabakar@gmail.com

Drug Induced Parkinsonism (DIP) can be described as reversible development of Parkinsonian syndrome in patients treated with drugs which impair dopamine function. It includes symptoms such as tremor, muscular rigidity and bradykinesia. Gastrointestinal prokinetics, calcium channel blockers, modern atypical antipsychotics, and antiepileptic drugs may cause DIP. This report is about a 40-year-old female patient who developed a DIP after taking the antipsychotic medication combination (chlorpromazine and trifluperazine) for insomnia after being prescribed from a psychiatric clinic. After four weeks of initiation of treatment, she developed tremors, muscular rigidity and slowness in movements. The patient was admitted with the following complaints and then the drugs chlorpromazine and trifluperazine were stopped. The patient was then treated with tablet levodopa and carbidopa 110 mg, trihexiphenidyl 2 mg and tablet alprazolam 0.25 mg after which she gradually improved and was feeling better after a week. Atypical antipsychotics indicated for psychiatric disorders have high potential to cause extrapyramidal symptoms. Hence, for the treatment of insomnia newer drugs such as zolpidem and zaleplon can be used to minimise the chances of occurrence of DIP.

Antipsychotics, Drug induced parkinsonism, Extrapyramidal symptoms

Case Report

A 40-year-old female patient was admitted to the Neurology ward with the complaints of generalised weakness for 10 days, and change in gait for the past 15 days. She also had complaints of slow walking, shaking in the left jaw and resting tremors in upper limbs. Medical history revealed that the patient had been on treatment with a private psychiatry clinic for insomnia since two months. Her medication history for insomnia included oral chlorpromazine 50 mg, benzhexol 2 mg, trifluperazine 5 mg (trinicalm forte), promethazine 25 mg (phenergan), nitrazepam 5 mg (nitrosum), and tablet etizolam 0.5 mg, escitalopram 50 mg (Etilam DS). After four weeks of therapy, she developed the movement disorder and resting tremors.

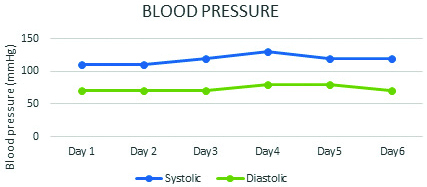

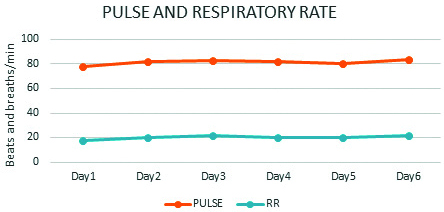

At the time of clinical examination, patient was conscious, oriented and afebrile. Her vital signs like blood pressure- 110/80 mm Hg, pulse rate- 76 beats/min, respiratory rate- 22 breath/min, temperature- 98.6°F was found to be normal.

The clinical findings of the patient revealed bilateral cogwheel rigidity right limb greater than the left, reduced arm swing, bradykinesia, resting tremors, slow stepping gait, and involuntary jaw movements at left-side. Neurological examinations show absence of gaze palsy, facial asymmetry. Extra Ocular Muscle (EOM) function of both eyes was normal and the pupil equally reacting to light. Her Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score was found to be 30/30. Laboratory parameters such as complete blood count, liver function test, renal function test and thyroid test were examined and found to be within the normal limits. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) revealed no significant abnormalities. Electro Cardiogram (ECG) sinus rhythm was normal. The provisional diagnosis was given as DIP according to the history, clinical findings and laboratory investigations.

The offending drugs tifluperazine and chlorpromazine were stopped. The patient was treated with drug combination levodopa 100 mg, carbidopa 10 mg twice daily and trihexiphenidyl 2 mg once daily. After the treatment resting tremors and bradykinesia started to subside from third day. By fifth day patient responded well to the treatment, with normal gait, alleviation of cogwheel rigidity and involuntary movements. During hospitalisation vitals were checked daily and found to be normal [Table/Fig-1,2]. For insomnia, alprazolam 0.25 mg was given at night from the first day to seventh day.

Chart of Pulse rate (beats/min) and Respiratory Rate (RR breaths/min).

The patient was discharged after a week of treatment, as the symptoms of resting tremors and bradykinesia subsided and the condition improved. Patient was counselled regarding sleep hygiene as to avoid caffeine at night, not to have day time naps, set the body clock by going to bed and rise at the same time every day. Discharge medications included Tab. zolpidem 10 mg HS and trihexiphenidyl 2 mg twice daily for seven days. On follow-up after a week, the patient was stable and had no complaints of extrapyramidal effects.

Discussion

The DIP can be described as reversible of parkinsonian syndrome in patients as a result of drugs which impair dopamine function [1]. Parkinsonian syndromes include symptom complexes such as tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, loss of postural reflexes and freezing. Drugs that impair the dopamine function like gastrointestinal prokinetics, calcium channel blockers, modern atypical antipsychotics and antiepileptic drugs are associated with the DIP [2]. The time for recovery of DIP after the withdrawal of causative drug may vary from days to years [3]. DIP is second in order, reckoning for up to 20% of the Parkinson Disease (PD) cases [4]. In most cases, DIP is reversible but in 25% of cases the symptoms gets persisted even after withdrawing the causative agent [5].

Antipsychotic drugs are used in the treatment of severe psychiatric disorders. It is used in the treatment of acute psychotic, manic and psychotic-depressive disorders as well as chronic psychotic disorders including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and delusional disorders. Conventional phenothiazines, thioxanthene butyrophenones and neuroleptics were replaced by the newer “second generation” antipsychotics in the clinical practice [6].

Conventional antipsychotic drugs (e.g., haloperidol, fluphenazine) which have high potency, affinity and avidity for D2 receptors shows relatively high risk of extrapyramidal symptoms even at moderate doses by interfering with dopaminergic neurotransmission. The neurological adverse reactions include gradually developing Parkinsonian bradykinesia, tardive dyskinesia, dystonia and akathisia (motor restlessness) [7]. Parkinsonism is likely caused due to the decreased dopaminergic transmission in the basal ganglia of forebrain [8].

The management of DIP involves the cessation of the causative drug. Patients who are taking the dopamine antagonists for simple ailments such as Gastrointestinal disturbance, headache, dizziness or insomnia should be stopped [9]. Pharmacologic management involves the use of levodopa, amantadine and anticholinergics including benzotropine and trihexiphenidyl. These agents have the ability to abate the symptoms of DIP, usually within weeks to months after the cessation of the offending drug [10].

In the case reported here, the patient was treated with antipsychotics (chlorpromazine and trifluperazine) for insomnia. The recommendation of antipsychotics for insomnia is considered to be appropriate in patients with mental illness such as bipolar disorder with mania. Thus, the selection of drug for insomnia should be personalised based on patient individual characteristics like age, gender, concomitant medical conditions and history of disease. The rational selection of drug therapy should be considered to reduce the risk of extrapyramidal symptoms which helps in providing best quality of care.

In this case, Naranjo algorithm was used to determine a plausible reaction due to antipsychotics. Based on the total score of 7, this DIP was categorised as “probable” reaction to antipsychotics (chlorpromazine and trifluperazine) administration [11].

Conclusion(s)

Antipsychotic agents were usually prescribed for the various psychiatric disorders. The major adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs were parkinsonism, dyskinesia and akathisia. Those drugs which cause dopamine antagonistic effect have high potency to cause DIP. Hence for the minor ailments such as insomnia, gastrointestinal disturbances, headache dopamine antagonist should be avoided. For the treatment of primary insomnia newer drugs such as zolpidem and zaleplon can be given to minimise the chances of occurrence of DIP.

Author Declaration:

Financial or Other Competing Interests: None

Was informed consent obtained from the subjects involved in the study? Yes

For any images presented appropriate consent has been obtained from the subjects. NA

Plagiarism Checking Methods: [Jain H et al.]

Plagiarism X-checker: Jan 08, 2021

Manual Googling: Apr 10, 2021

iThenticate Software: Apr 28, 2021 (14%)

[1]. López-Sendón J, Mena M, G de Yébenes J, Drug-induced ParkinsonismExpert Opinion on Drug Safety 2013 12(4):487-96.10.1517/14740338.2013.78706523540800 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[2]. Blanchet P, Kivenko V, Drug-induced parkinsonism: Diagnosis and managementJournal of Parkinsonism and Restless Legs Syndrome 2016 6:83-91.10.2147/JPRLS.S99197 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[3]. Tinazzi M, Antonini A, Bovi T, Pasquin I, Steinmayr M, Moretto G, Clinical and [123I] FP-CIT SPET imaging follow-up in patients with drug-induced parkinsonismJournal of Neurology 2009 256(6):910-15.10.1007/s00415-009-5039-019252795 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[4]. Micheli F, Cersosimo M, Drug-induced ParkinsonismParkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders, Part II 2007 :399-416.10.1016/S0072-9752(07)84051-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

[5]. Shin H, Chung S, Drug-induced ParkinsonismJournal of Clinical Neurology 2012 8(1):1510.3988/jcn.2012.8.1.1522523509 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[6]. Leslie D, Rosenheck R, From conventional to atypical antipsychotics and back: Dynamic processes in the diffusion of new medicationsAmerican Journal of Psychiatry 2002 159(9):1534-40.10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.153412202274 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[7]. Gardner D, Modern antipsychotic drugs: A critical overviewCanadian Medical Association Journal 2005 172(13):1703-11.10.1503/cmaj.104106415967975 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[8]. Baldessarini RJ, Tarazi FI, Drugs and the treatment of psychiatric disorders: Antipsychotic and antimanic agents. In: Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Gilman AG, editorsGoodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics 2001 10th edNew YorkMcGraw-Hill Press:485-520. [Google Scholar]

[9]. Sethi K, Movement disorders induced by dopamine blocking agentsSeminars in Neurology 2001 21(01):59-68.10.1055/s-2001-1312011346026 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[10]. Hardie R, Lees A, Neuroleptic-induced Parkinson’s syndrome: Clinical features and results of treatment with levodopaJournal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 1988 51(6):850-54.10.1136/jnnp.51.6.8502900293 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

[11]. Naranjo C, Busto U, Sellers E, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts E, A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactionsClinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1981 30(2):239-45.10.1038/clpt.1981.1547249508 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]