‘Body image’ is the self-concept of one’s own body which is a multidimensional concept incorporating perceptual, attitudinal and affective components [1]. Self-concept is defined as cognitive evaluations about oneself, one’s thoughts, beliefs and attitudes (John Hattie, 1992) in relation to the world and the social interactions in which one is involved. It is either positive or negative self-evaluation or identification that is thought to motivate and structure behaviour [2]. Thus, body image is correlated to self-esteem and eating behaviour [3].

There is an increasing trend in contemporary society to place emphasis on physical attractiveness which is attributed to slimness [4] and adolescents, in particular, place considerable emphasis on this [5]. Body image can be powerfully influenced and affected by cultural messages and societal standards of appearance and attractiveness [6]. The social pressure to be thin and the stigma of obesity lead to unhealthy eating practices and poor body image [7]. Discourses in media map their bodily needs are constantly bombarded with visual images of ideal bodies against which they measure their own [8-10].

The feeling of discrepancy between an individuals’ actual and ideal body image is defined as body dissatisfaction [11]. This might lead to a change in their eating behaviour and behavioural changes which are common in adolescence. Dieting is a corollary to body dissatisfaction and is a common practice to achieve desirable body shape [12]. However, adolescence too is a timely period for the adoption and consolidation of sound dietary habits. The nutrition needs of this period are the greatest, failing which may have a carryover effect into the adulthood and particularly in girls, may lead to the cycle of intergenerational malnutrition [13]. Thus, it is imperative to address these key factors and intervene timely. In this background, authors had planned to conduct the study among the adolescent girls of an urban slum (service area) with the aim of assessing the perception of body image among the adolescent girls of our study area and explored if it affected their eating behaviour.

Materials and Methods

An explanatory mixed method design (Quantitative Descriptive-Qualitative) was adopted for present study, which was community based, conducted in a sample of 250 adolescent girls in the service area (an urban slum) of JIPMER, Pondicherry, India during October 2007 to January 2009. The quantitative results were obtained in the first phase by an interview administered questionnaire by the principal investigator and the qualitative (text) data were collected in the second phase by means of six Focus Group Discussion (FGD) conducted in a subsample of the study participants to explain and elaborate the quantitative results. Ethical clearance from the institute (JIPMER) was obtained and consent from the participants or the guardians in minor was obtained for present study.

Inclusion and Exclusion criteria: All the sampled adolescent girls (n=250) were included in the study. Among the total number of adolescent girls in the study frame (n=507), the pregnant and lactating adolescent girls were less in number and thus were excluded.

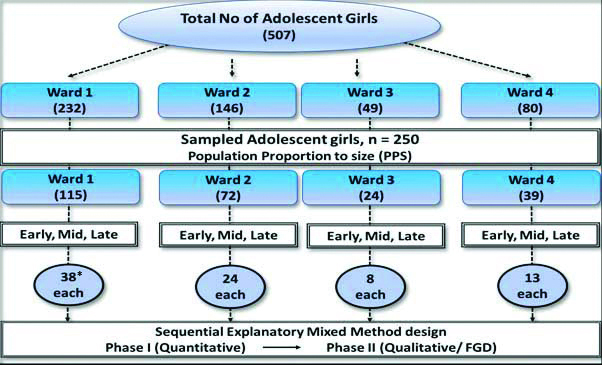

Sample size calculation: The sample size was calculated to be 250 considering the prevalence of ‘skipping breakfast’ among adolescent girls as 34% [12] using the formula; n=Z2 P (1-P)/d2 {n=sample size, Z=statistics corresponding to 95% confidence interval, P=Prevalence, assuming a relative precision of 20% (d) and a power of 80% and a dropout rate of 20%}. A proportionate sampling method was adopted to draw sample of girls from the four wards [Table/Fig-1] of the service area. The required number of study participants (n=250) was drawn from the list of total adolescent girls (a total of 507 as obtained from the enumeration register for that year) by Simple Random Sampling technique.

Selection of the study participants (n=250).

*38 participants are taken in 3 (Early, Middle & Late). The total is 114 and has been rounded off to 115

Study procedure: The age group of 10-19 years was considered as adolescence (WHO) [13] and for interpretation of results authors divided them as Early; 10-13, Mid; 14-16, Late; 17-19 years as the different age groups in present study. Operationally, three parameters were considered for present study; self-perception of body shape (what is their perception of their own body), perception of healthy body shape (what is an ideal body according to them) and their actual body weight (BMI, WHO Asian standards) [14]. For the qualitative FGDs, a 32-item check list was followed according to the consolidated Criteria For Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) [15] pertaining to three domains with respect to the research team and reflexivity, study design and conduction, data analysis and documentation of findings by the principal investigator who is formally trained in qualitative research. The ‘discussion guide for the FGD’ was formulated and pertained to the key domains with various probes and prompts for facilitating the discussion conducted by the moderator (principal investigator) in the local language with appropriate audio recording of the sessions after obtaining consent from the study participants.

The key informants were contacted and the participants were intimated about the time and venue and were mobilised for the FGD and the logistics were facilitated [Table/Fig-2]. Separate FGDs were conducted among the different age groups of the adolescence to ensure homogeneity among the participants (restricted to 8 to 10 per FGD) and to compare the views across the age groups.

Active Focus Group Discussions (FGD) among the adolescent girls.

Statistical Analysis

Data was analysed by SPSS (version 13.0) and N-Vivo 8 (Demo version) for the quantitative and qualitative data respectively. The field notes from the decontextualised text of the transcript pertaining to respective themes were quoted as translated versions (English) of the same text obtained originally in the local language (Tamil).

Results

1. Body image (Self-perception of own body shape, perception of a healthy body shape and the actual body shape): The study participants were asked about ‘how important it was to them to maintain their body shape’. It was important to 96% of girls and not important to 4% of the respondents. Additionally, there was a significantly higher proportion (p<0.05) in each of the individual age groups for whom it was important (very important and moderately important) [Table/Fig-3]. They were asked about what a ‘healthy body shape’ meant to them. A majority (59.6%) of them perceived it as being ‘normal’ (n=149). However, others felt as being ‘thin’ (34.8%) and being ‘fat’ (5.6%) too as healthy body shapes. The perceptions across all the age groups of adolescence (early, mid and late) were similar. However, in each of the individual age groups, there were a significantly higher proportion (p<0.05), who considered ‘being thin’ as the healthy body shape than ‘being fat’ [Table/Fig-3].

Adolescent girls’ perception on importance of maintaining their own body shape and their perception of a healthy body shape (n=250).

| Categories | Early adolescents | Mid adolescents | Late adolescents | Total |

|---|

| N | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

|---|

| Very important | 68 | 82 | 71 | 86 | 75 | 89.3 | 214 | 85.6 |

| Moderately important | 10 | 12 | 9 | 11 | 7 | 8.3 | 26 | 10.4 |

| Not important | 5 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2.4 | 10 | 4 |

| Total | 83 | 100 | 83 | 100 | 84 | 100 | 250 | 100 |

| Perceptions of ‘Healthy body shape in adolescence |

| Categories | Early adolescents | Mid adolescents | Late adolescents | Total |

| N | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Fat | 7 | 8.5 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 2.4 | 14 | 5.6 |

| Thin | 31 | 37.3 | 27 | 32.5 | 29 | 34.5 | 87 | 34.8 |

| Normal | 45 | 54.2 | 51 | 61.4 | 53 | 63.1 | 149 | 59.6 |

| Total | 83 | 100 | 83 | 100 | 84 | 100 | 250 | 100 |

Chi-sq=2.273, df=4, p=0.686; (SEP=Standard Error difference between two Proportions); Important and not important: SEP=7.66, p<0.05 (Early), SEP=6.01, p<0.05 (Mid), SEP=4.93, p<0.05 (Late); Chi-sq=3.674, df=4, p=0.452; Cat fat and thin: SEP=9.04, p <0.05 (Early), SEP=8.09, p<0.05 (Mid), SEP=6.53, p <0.05 (Late)

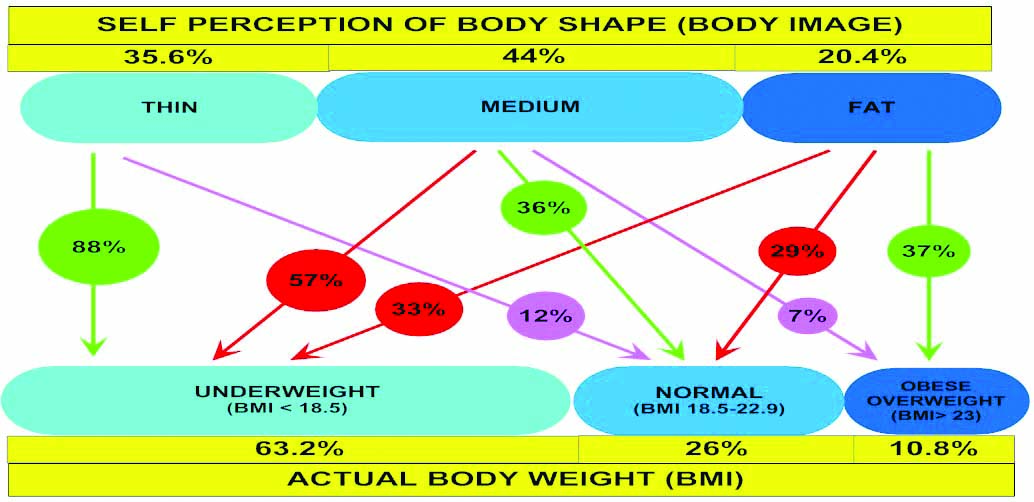

Their ‘self-perception of their own body shape’ [Table/Fig-4] was normal in 110 respondents (44%), thin in 89 (35.6%) and fat in 51 (20.4%). Their self-perception about themselves was compared against their actual Body weight (BMI, Asian standards). Among those who felt that they had normal body shape, about 57.3% were underweight, 35.5% were normal and 7.3% were overweight or obese. Among those who felt that they were thin, 87.6% were actually underweight, 12.4% were normal and nil were overweight. Among those who felt that they were fat, about 33.3% were underweight, 29.4% were normal and 37.3% were overweight or obese. The comparison between ‘self-perception of body shape’ and ‘actual body mass index’ [Table/Fig-4,5] showed no agreement (kappa 0.116) and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001).

Qualitatively, it was learnt from the FGD that, there was a preference for ‘being thin’ among the girls. Those who were even ‘very thin’ (as told by others) wanted to be ‘normal’ but never wanted to be ‘fat’ at any cost. They told that if one was fat, people often passed obscene comments while walking on the street. It gave them poor self-esteem and made them feel very bad and conscious. The feeling as expressed by a participant was, ‘I feel very bad being called fat. I have been taking honey in luke warm water (A local remedy) for a month’. For them, being thin made them fit into any dress and they also longed to be thin like their favourite TV personalities. However, very few of them believed that ‘being fat’ was better because strength was needed for sustaining stress in life. According to their culture, if somebody was fat, they were believed to be a symbol of richness or aristocracy. Being very thin was also cursed by the community. The concern expressed by a participant was, ‘I feel bad for not gaining weight. People everywhere in the neighbourhood say that I am cursed and probably have TB’

It was also discussed in the FGD that, apart from maintaining ‘body shape’, they should look neat, clean and nicely dressed to reflect their personality in the society. They believed that ‘healthy habits’ should be developed for ‘inner peace’ which got reflected on face. They preferred to be dressed up in a culturally acceptable way. A few stressed on developing ‘self-identity’ and ‘self- look’ in society than imitating somebody else’s style.

2. Role of food and exercise in maintaining body shape: To the adolescent girls, food was believed to be either ‘fat’ or ‘healthy’. Commonly considered ‘fat foods’ were butter, cheese, ghee, non-vegetarian items, egg and the ‘healthy foods’ were vegetables, green leafy vegetables, milk etc. About 78.8% (n=197) of girls had some knowledge of above-mentioned foods. On asking those girls (n=250) about the means and ways to maintain a healthy body shape [Table/Fig-6], about 7.2% had no idea about it and about 74.4% (n=186) mentioned the role of healthy food intake and about 40% mentioned the role of exercise. However, about 6.8% (n=17) too mentioned the role of dieting as one of the means to achieve a healthy body shape (5% early, 10% mid and 6% late adolescents). The other responses were drinking plenty of water, sleeping well, being peaceful etc.

Comparison of ‘Self-perception of Body Shape’ and Actual ‘Body Weight’.

| Self-perception of body shape | Actual body weight (Body mass index) Kg/m2 Underweight (<18.5), Normal (18.5-23), Overweight (23-25), Obese (>25) |

| Category | Underweight | Normal | Overweight, Obese | Total |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Thin | 78 | 87.6 | 11 | 12.4 | 0 | 0 | 89 | 100 |

| Normal | 63 | 57.3 | 39 | 35.5 | 8 | 7.3 | 110 | 100 |

| Fat | 17 | 33.3 | 15 | 29.4 | 19 | 37.3 | 51 | 100 |

| Total | 158 | 63.2 | 65 | 26.0 | 27 | 10.8 | 250 | 100 |

Kappa=0.116 (p<0.001); Chi-square=70.529, df=4, p=<0.001

Comparison of ‘Self Perception of Body Shape’ and ‘Actual Body Weight’

Key to maintain a ‘Health Body Shape’ as perceived by the adolescent girls.

| Categories | Early adolescents (n=83) | Mid adolescents (n=83) | Late adolescents (n=84) | Total (n=250)* |

|---|

| N | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

|---|

| No idea | 9 | 11 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 18 | 7.2 |

| Healthy food intake | 59 | 71 | 58 | 70 | 69 | 82 | 186 | 74.4 |

| Exercise | 33 | 40 | 29 | 35 | 38 | 45 | 100 | 40 |

| Dieting | 4 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 17 | 6.8 |

| Others | 25 | 30 | 18 | 22 | 40 | 48 | 83 | 33.2 |

*multiple answers given

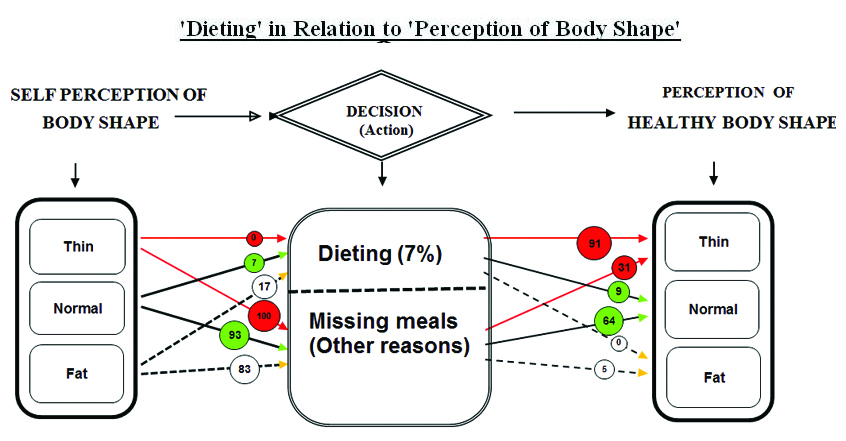

3. Practice of dieting to maintain body weight: In present study, about 64.8% (n=162) missed any meal a day but among them about 6.8% (n=11) missed it purposefully for the purpose of losing weight i.e., dieting. When the practice of dieting (among all causes of missing any meal) was compared against their self-perception of their own body shape [Table/Fig-7], it was noted that among those who dieted, there were only those who felt their body shape as fat (17.1%) or normal (6.8%) but none (0%) among those who considered themselves as thin.

Self perception of body image and the practice of dieting (n=162).

| Self-perception of body shape (Body image) | Reason for missing meal |

| Body shape | Dieting | *Reasons other than dieting | Total |

| n | % | n | % | n (%) |

| Thin | 0 | 0 | 54 | 100 | 54 (100) |

| Normal | 5 | 6.8 | 68 | 93.2 | 73 (100) |

| Fat | 6 | 17.1 | 29 | 82.9 | 35 (100) |

| Total | 11 | 6.8 | 151 | 93.2 | 162 (100) |

Chi-square=9.861, df=2, p=0.007; * Reasons for missing a meal include ‘dieting’ and those ‘other than dieting’. ‘Other than dieting’ includes ‘lack of time to eat’, ‘angry’, ‘not feeling hungry’, ‘food not cooked at house’, ‘feeling sleepy’ etc.

It was noted from the FGDs that being thin was seen as the desirable body shape for many adolescent girls in the community. They strove to achieve this goal by applying dietary restraints. The major response in this regard was that they wanted to be either thin or normal in weight but did not want to be fat by any means. It was believed that being fat made one ‘feel lazy’, ‘difficult to walk’ or even ‘difficult to breathe’ and increased the susceptibility to diseases. They had their own perception of the reasons for a fatty body texture and suggested various measures that they were aware of, in the FGDs [Table/Fig-8,9]. As food was attributed to make one fat or thin, some adolescent girls skipped major meals to become slim or avoided taking any solid food (especially rice) for liquid diet (juice or milk). As told by a respondent,

Exploration of the respondents’ perspective of a fatty body shape.

| Theme | Possible reasons | Explanation/Contextual factors | Measures usually adopted by the respondents |

|---|

| Diet | Overeating | More appetite/cooking of favourite foods/festive occasions | Control eating more at once |

| Skip the previous/next meal if favourite food is cooked |

| Take water before eating |

| Prefer liquid over solid diet |

| Dieting keeps one fit and aids good health |

| More of fatty food in diet | The excess fat deposits in body | Native measures for decreasing appetite/Drinking warm water/ native measures for fat loss |

| Less of healthy food in diet | Regulates body weight but eating vegetables are not always tasty/ fruits are expensive to eat | Must eat vegetables and fruits whenever available |

| Excess salt intake | Excess salt retains water in body to make one look fat | Avoid salt intake/Less salt intake |

| Physical inactivity | Mechanisation of routine household work (mixi, rice cooker etc.) | Lack of time/Busy work schedule | Exercise/Walking daily/Asana/ Yoga |

| Beliefs | Sleeping immediately after food | Food is retained and not metabolised | Eat early and sleep after 2 hours |

| Genetic constitution | Heard from elders | One must check on food intake |

| Accumulation of air inside body | Some typical category that they have seen | Should avoid foods that accumulates gas in body like roots and tubers (potato) |

| Remaining happy always | Because one is free from stress | - |

Conceptual representation of ‘dieting’ in relation to ‘perception of body shape (self-perception of own body shape and perception of healthy body shape).

‘I frequently diet because I want to be thin. If I take breakfast, I miss lunch or if not, the lunch I miss dinner. When my favourite food is prepared at home, I skip my breakfast so as to eat much of it in lunch, or else, I would feel guilty of taking excess food’

Discussion

Present study evidenced how the adolescent girls had altered body image even though they belonged to the urban slum with poor social status (low median per capita income), since body image perception is entirely a behavioural process. Present study too attempted to show the extent of concern for a thin body image at psychological level of the adolescent girls.

The Principles in health psychology [16] conceptualises body image as a product of perception- as constructed through a process in which we perceive our own bodies and other people’s bodies, make comparisons and internalise these comparisons and alter our body image in the light of such comparisons. In present study, the intent could be observed from the qualitative results; ‘skipping meals have become my habit and I don’t feel hungry at all’ and ‘only when you are thin you will fit into any dress’. It was noted that the girls had vulnerability to the cultural demands and pressures of being thin from their friends and surroundings and thus exhibited a greater interest in physical appearance. However, even though body image is reinforced in the media though the ubiquitous use of images of thin women in television, movies, and advertisement, it is a social issue arising out of the cultural standards [17,18]. Some of our participants (especially the late adolescent age groups) opined that even though they admired the TV personalities, they did not prefer to be like them because the life style adopted by the celebrities was not permitted by their culture.

It is said that initially, the perceptual processes of body image are conceived narrowly and later on, this takes the shape of body distortion, a marked alteration in the perception of body size- perceiving oneself as fat even when one is dangerously underweight [4]. Such an inclination towards being thin was also evidenced in present study quantitatively. There was no agreement between what they perceived of themselves and what they actually were [Table/Fig-5]. Thus, it was clear that whatever was said by them was based on a wrong notion about their body. It was unacceptable that girls in present study who thought themselves as normal or fat were actually underweight. In a study on adolescents of Hong Kong [19] stated that underweight or normal weight adolescents who perceived themselves to be overweight were at an increased risk for eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa. The adolescents in present study appeared to be constantly under the spell of this negative body image which may be noticed in the statement; ‘if I take breakfast, I miss the lunch or if not lunch, I miss the dinner’. Hence, it appeared that the tendency to wear a thin look was so strong that they did not know that they were becoming underweight in the process.

Body image was of paramount importance in adolescence as commented by Mooney E et al., who qualitatively explored this among adolescent girls of the Republic of Ireland [20]. It was found in present study too that maintenance of body shape was important to 85.6% of girls; at times they skipped meal or adopted methods to lose fat (honey in luke warm water) and even exercised control over their preferred foods for the fear of becoming fat. As confessed by a participant, ‘I like ice cream very much but I control eating because it would make me fat’. It signified that there was a struggle in adolescent mind to go for taste or to exercise control over it. Additionally, in the present study, about 34.8% still considered ‘being thin’ as being healthy. However, about 5.6% even considered ‘being fat’ too was healthy as they believed that extra strength was required to sustain stress and for the ‘subjective feeling’ of richness of one’s social status as believed in their culture (FGD).

The present study underlined the role of food and exercise as important for the adolescent girls in maintaining their body weight. Importance of ‘dieting’ was also stressed among few girls. Change in the level of physical activity in daily life (due to mechanised means of working) was also considered to make one fat and some form of physical exercise must be adopted as means to maintain one’s body weight was suggested by the participants. Jankauskiene R et al., studied the association of body image concerns in Lithuanian college going girls with the health compromising physical activity behaviours and reported that the main reason to engage in physical activity (among the adolescent girls) was to improve the body image (45.2%), while the health improvement motive was left out in the second place (33.6%) [21]. Improving appearance and body shape were the main reason for weight control behaviours as documented in a cross-sectional study among college going adolescent girls from Coimbatore [22]. The same ideas emerged from the FGD of the present study.

Body image is the perception of one’s body, while body image dissatisfaction is the dissatisfaction with this perception, making it a subjective experience rather than based on weight or actual body size [17]. This dissatisfaction in turn is accompanied by poor self-esteem which was also noted in present study. Additionally, wearing a good look gave them confidence in society similar to the findings documented by Mooney E et al., in Irish adolescents [20]. In the present study it was observed that being thin was the most desirable body shape and the girls strove to achieve this by dietary restraint. Neumark-Sztainer D and Hannan PJ documented the weight related behaviours in adolescents in a nationwide school based study which reported about 45.4% girls dieted and 13.4% even reported disordered eating and for 88.5% of those dieted, the reason was to ‘look better’ [23]. As said by a participant of present study, ‘When I take a lot of food, I skip the next meal. Only by this, one can reduce’. Thus, the propensity towards thinness was so much compelling that they disliked being fat. Most of the adolescents of present study suffered from the dilemma for not being able control their desire for good food and at the same time applying restraint on gaining weight due to overeating. As illustrated, ‘I think of controlling food because I am fat but every time I forget and eat more. There are cultural ideals of masculine and feminine beauty, as drawn on popular representations. Investigations of these ‘ideals’ frequently employ silhouette scales and measure how far and in what manner the individual deviates from their ideal [24].

In depicting body image, the perceptual component refers to how one saw one’s size, shape, weight, features, movement and performance, while the attitudinal component refers to how one feel about these attributes and how one’s feelings direct one’s behaviours [16]. To show these complex conceptual phenomena of attitude governing behaviour, in present study, it was considered specifically those who missed meals for dieting (6.8%) (n=18) and tried to show how their perceptions were reflected in their behaviour. Interestingly, in the present study it was observed that those who perceived themselves as ‘thin’; were not dieting (but were missing meals for other reasons). On the other hand, only either of those who perceived themselves as fat or normal was dieting [Table/Fig-8]. Conversely, those who dieted had the opinion that being ‘thin’ was healthy (91%) but for none (0%) of them, being ‘fat’ was healthy. This observation was obvious in the sense that, girls who dieted also had the perception that being thin was the ideal body shape. The similar findings are also noted by Ganesan S et al., [22]. However, in subtle plane, interplay of these factors played their roles.

Limitation(s)

Within the scope of the mixed method design, authors could substantiate the results obtained during the quantitative interviews and could explore in depth about the perception of the body image and the gained insight into some key behavioural issues. Their reflections or understanding on the acceptance of an ideal body image as well the societal perspective of an ideal body image could be explored. However, authors could not measure the extent of weight control practices in present study quantitatively which could have helped in planning specific interventions in this regard. The relationship between weight status and body image perception is complex and the role of factors like internalisation of body ideals, weight related pressures and concerns, and the range of social influences must be explored to design specific interventions for them. They should be counselled to produce a behaviour change and the strategy for sustained motivation from childhood and a ‘positive role modelling’ is essential as adolescence is the time to exercise behavioural autonomy and habits developed at this age, persist into adulthood.

Conclusion(s)

The self-perception of body shape in the current study showed a preference for thinness and the sense of body dissatisfaction among them was obvious and according to them, it affected their self-esteem. Consequent upon this aesthetic conflict in their mind, it tried to acquire the desired body shape by taking recourse to several unhealthy means. The adolescents are the ‘human capital’ as regards to their positive role in future and thus should be counselled to produce a behaviour change in them.

Chi-sq=2.273, df=4, p=0.686; (SEP=Standard Error difference between two Proportions); Important and not important: SEP=7.66, p<0.05 (Early), SEP=6.01, p<0.05 (Mid), SEP=4.93, p<0.05 (Late); Chi-sq=3.674, df=4, p=0.452; Cat fat and thin: SEP=9.04, p <0.05 (Early), SEP=8.09, p<0.05 (Mid), SEP=6.53, p <0.05 (Late)

Kappa=0.116 (p<0.001); Chi-square=70.529, df=4, p=<0.001

*multiple answers given

Chi-square=9.861, df=2, p=0.007; * Reasons for missing a meal include ‘dieting’ and those ‘other than dieting’. ‘Other than dieting’ includes ‘lack of time to eat’, ‘angry’, ‘not feeling hungry’, ‘food not cooked at house’, ‘feeling sleepy’ etc.